Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

News Release Office of Cultural Affairs FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact Michael Ogilvie, Director of Public Art, City of San José Office of Cultural Affairs (408) 793-4338; [email protected] Elisabeth Handler, Public Information Manager Office of Economic Development (408 535-8168); [email protected] San José Student Poetry Contest Supporting a Creative Response to Litter SAN JOSE, Calif., (Oct. 15, 2018) The City of San José’s Public Art Program and Environmental Service Department are collaborating with Mighty Mike McGee, current Poet Laureate of Santa Clara County, on a new initiative titled “Litter-ature,” a creative response to litter awareness and prevention through a student poetry contest. Outreach support is also being provided by San José Parks, Recreation & Neighborhood Services’ Anti-Litter Program. Middle school and high school students in the City of San José are invited to submit up to five short poems that inspire people to put their trash into public litter cans, protecting nature, wildlife, and our streets. Content may inspire awareness, personal responsibility, connections to community and environmental responsibility. The contest will be juried by professional poets and community members who will select the winning poems that will become permanent artwork affixed to 500 new public litter cans to be installed in San José business districts in 2019. In addition to the winning poems being creatively featured on the litter cans, prizes will be awarded to honorable mentions. Submissions will be accepted on line at the contest website: www.litter-ature.info. Young poets are encouraged to work with short form poetry, such as haiku and/or tanka, a form similar to a haiku, with a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable count. -

SLAM AS METHODOLOGY: THEORY, PERFORMANCE, PRACTICE by Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the R

SLAM AS METHODOLOGY: THEORY, PERFORMANCE, PRACTICE by Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan (2014) SLAM AS METHODOLOGY: THEORY, PERFORMANCE, PRACTICE Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan Master of Arts Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis study theorizes slam as a research methodology in order to examine issues of access and representation in arts-based educational research (ABER). I explain how I understand and materialize slam as a research methodology that borrows concepts and frameworks from other methodologies such as, ABER, participatory action research (PAR) and theoretical underpinnings of indigenous theory, feminist theory and anti- oppressive research. I argue that ABER and slam, as a particular form of ABER, needs to ‘unart’ each other to avoid trying to situate slam within the Western canon of ‘high arts’. I apply PAR methodology to discuss participant involvement in the research process and use anti-oppressive research to speak about power and race in slam. Finally, I argue that a slam research methodology has the ability to enable critically conscious communities. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am overflowing with gratitude. A great deal of this is due to the loving, inspiring and wise community of family, friends, and professors, with whom I have been blessed with. Most importantly, I would like to thank my parents, whose passion for learning and pursuit of university education despite impossibly difficult conditions were sources of inspiration and strength throughout my studies. -

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits?

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits? Cornelia Gräbner erformance poetry in the Western world festival hall. A poem will be performed differently is a complex field—a diverse art form that if, for example, the poet knows the audience or has developed out of many different tradi- is familiar with their context. Finally, the use of Ptions. Even the term performance poetry can easily public spaces for the poetry performance makes a become misleading and, to some extent, creates strong case for poetry being a public affair. confusion. Anther term that is often applied to A third characteristic is the use of vernacu- such poetic practices is spoken-word poetry. At lars, dialects, and accents. Usually speech that is times, they are included in categories that have marked by any of the three situates the poet within a much wider scope: oral poetry, for example, or, a particular community. Oftentimes, these are in the Spanish-speaking world, polipoesía. In the marginalized communities. By using the accent in following pages, I shall stick with the term perfor- the performance, the poet reaffirms and encour- mance poetry and briefly outline some of its major ages the use of this accent and therefore, of the characteristics. group that uses it. One of the most obvious features of perfor- Finally, performance poems use elements that mance poetry is the poet’s presence on the site of appeal to the oral and the aural, and not exclu- the performance. It is controversial because the sively to the visual. This includes music, rhythm, poet, by enunciating his poem before the very recordings or imitations of nonverbal sounds, eyes of his audience, claims authorship and takes smells, and other perceptions of the senses, often- responsibility for it. -

Poetry in August @ the Cantab Lounge Bostonpoetryslam On: Facebook * Yahoo! * Tumblr

Poetry in August @ the Cantab Lounge bostonpoetryslam on: Facebook * Yahoo! * tumblr. http://www.bostonpoetryslam.com Wednesday, August 6 — With all of New England’s slam teams, coaches, and entourage out of town at the National Poetry Slam, our bartender will step onto the stage to present the Adam Stone Anti-Slam. Adam has promised to present a feature of his excellent poetry, prose, and in-between work… That is, unless he can convince some other old-school all-star poets who are also skipping out on NPS to show up and produce a show with him. Or against him. Or at him. Or whatever: all he knows is that it won’t be a slam, but it will definitely be the ONLY poetry place to be if you aren’t trekking to Oakland to watch NPS this week. Final open slam in the 8x8 series. Wednesday, August 13 — Jacob Rakovan is an Appalachian writer in diaspora. He is the author of The Devil’s Radio (Small Doggies Press, 2013) He is a 2011 New York Foundation for the Arts Fellow in Poetry and recipient of a 2013 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. He is co-curator of the Poetry & Pie Night reading series in upstate New York, where he resides with his five children and a mermaid. Champion of Champions poetry slam: Ellyn Touchette defends her title. Wednesday, August 20 — Tova Charles and Zai Sadler are The Hair and Teeth and Talk Tour, showcasing group and solo work from these two women who worked together on the fifth-place 2013 Austin Poetry Slam team. -

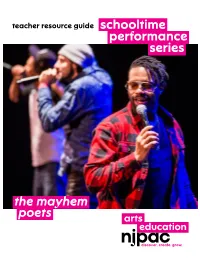

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

A Teacher's Resource Guide for the Mayhem Poets

A Teacher’s Resource Guide for The Mayhem Poets Slam in the Schools Thursday, January 28 10 a.m. Schwab Auditorium Presented by The Center for the Performing Arts at Penn State The school-time matinees are supported, in part, by McQuaide Blasko Busing Subsidy in part by the Honey & Bill Jaffe Endowment for Audience Development The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts provides season support 1 Table of Contents Welcome to the Center for the Performing Arts presentation of The Mayhem Poets ................................ 3 Pre-performance Activity: Role of the Audience .......................................................................................... 4 Best Practices for Audience Members ...................................................................................................... 4 About the Mayhem Poets ............................................................................................................................. 5 Slam poetry--the competitive art of performance poetry ............................................................................ 7 Slam Poetry--Frequently Asked Questions ............................................................................................... 8 Slam Poetry Philosophies ........................................................................................................................ 16 Taken from the website http://www.slampapi.com/new_site/background/philosophies.htm. .......... 16 Suggested Activity: Poetic Perspective ...................................................................................................... -

Marquis Burton

Marquis Burton 12 Middlebury Lane, Lancaster, NY 14086 | 716.998.2234 | [email protected] Teaching Experience___________________________________________________________________ Teaching Artist Sweet Home High School | Guest Poetry Instructor | November 2006 - Present North Park Academy Afterschool Program | December 2017 – March 2018 PS 197 and Say Yes Buffalo | February 2017 – June 2017 Gloria J. Parks Community Center | January 2017 – April 2017 Community Action Organization | Teaching Artist | October 2010 – May 2011 Lake Shore High School | Instructor | April 2010 · Collaborate with host organizations to develop and implement poetry and performance workshops for elementary, middle & high school students · Provide instruction and development in style; cultivating unique voices and enhancing self-confidence · Equip students with performance skills and tools to present original work for an audience · Give students the tools to host and manage their own final showcase Pure Ink Poetry Slam | Coach | April 2016 - Present · Lead team to their first Semi-finals and the highest ranking of any previous Buffalo spoken word team · Held weekly workshops and practices to improve both content and presentation UB Speaks | Co-Founder / Coach / Instructor | 2014 – 2016 · Provided critiques to small groups of writers; developing style, voice, and performance · Held individual mentoring sessions with poets to master content and style Shea’s Performing Arts Center | Instructor | 2010 · Partnered with Shea’s Education Department and local English -

Art, Identity, and Status in UK Poetry Slam

Oral Tradition, 23/2 (2008): 201-217 (Re)presenting Ourselves: Art, Identity, and Status in U.K. Poetry Slam Helen Gregory Introducing Poetry Slam Poetry slam is a movement, a philosophy, a form, a genre, a game, a community, an educational device, a career path, and a gimmick. It is a multi-faced creature that means many different things to many different people. At its simplest, slam is an oral poetry competition in which poets are expected to perform their own work in front of an audience. They are then scored on the quality of their writing and performance by judges who are typically randomly selected members of the audience. The story of slam reaches across more than two decades and thousands of miles. In 1986, at the helm of “The Chicago Poetry Ensemble,” Marc Smith organized the first official poetry slam at the Green Mill in Chicago under the name of the Uptown Poetry Slam (Heintz 2006; Smith 2004). This weekly event still continues today and the Uptown Poetry Slam has become a place of pilgrimage for slam poets from across the United States and indeed the world. While it parallels poetry in remaining a somewhat marginal activity, slam has arguably become the most successful poetry movement of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Its popularity is greatest in its home country, where the annual National Poetry Slam (NPS) can attract audiences in the thousands and where it has spawned shows on television and on Broadway. Beyond this, slam has spread across the globe to countries as geographically and culturally diverse as Australia, Singapore, South Africa, Poland, and the U.K. -

Poetry in July @ the Cantab Lounge Bostonpoetryslam On: Facebook * Yahoo! * Tumblr

Poetry in July @ the Cantab Lounge bostonpoetryslam on: Facebook * Yahoo! * tumblr. http://www.bostonpoetryslam.com Wednesday, July 2 — Boston Poetry Slam co-founder, winningest slam competitor ever, and honest-to-metaphor firework Patricia Smith will return to the Cantab tonight for a special summer holiday feature. Lauded by critics as “a testament to the power of words to change lives,” Patricia is the author of six acclaimed poetry volumes and the winner of a near-ridiculous amount of poetry awards. Get your life right and show up early to get in for this feature. No poetry slam tonight. Wednesday, July 9 — Nathan Comstock has been writing for years, but didn’t discover spoken word poetry until he moved to Boston from his hometown of Indianapolis. He is now a fixture at the Cantab’s open mic and the Untitled Open Mic in Lowell, which he represented at the National Poetry Slam in 2013. Nathan offers up poetry that’s upbeat, funny, often geeky and often in formal verse, including what may well be the Cantab’s favorite-ever villanelles. Sixth open poetry slam in the 8x8 series. Wednesday, July 16 — Right in the heart of our summer of slam falls our second NorthBEAST Regional Team Slam, featuring Urbana-NYC, Port Veritas, Slam Free or Die, and the Lizard Lounge! With just a few weeks left until the National Poetry Slam in Oakland, California, local teams will be putting the final touches on their A- game. Come get a look-see at what the NorthBEAST is bringing to NPS 2014. $5 cover tonight to fundraise for the home team’s trip to NPS. -

The Providence Poetry Slam Team

The Providence Poetry Slam Team For years the Providence Poetry Slam has sent a team to the competition, the only slam team in Rhode Island to compete and represent the city at the National Poetry Slam. This year is no different. Providence’s team is made up of Marlon Carey, Steve Labri, Devin Samuels and me, Christopher Johnson. We’ll be in Boston from Monday, August 12 through Saturday, August 17. The team’s first bout will be Tuesday, August 13 at Johnny D’s, which is located at 17 Holland St. in Somerville. The start time is 9 pm so if you are going to support the home team, please arrive early. These bouts tend to fill up quickly! The Providence Poetry Slam Team Marlon Carey is a poet who has been a member of both the Boston Poetry Slam and Boston Lizard Lounge Poetry Slam Teams. He is also a proud member of the Providence RI-based poetry troupe, Brother’s Keeper. Steve Labri is a Pawtucket native and the rookie of the team. When asked, “How did you get into poetry slam?” He simply replied, “I was a rapper, I went to my first slam and thought I could do it.” Devin Samuels is a Cranston resident and coach of the Conn youth slam team made from members of his present college, U Conn, and other youth from the surrounding community. Devin represented Providence on multiple youth slam teams and while this is his first adult slam, he is no stranger to the competition. Christopher Johnson is Providence’s present Grand Slam Champion representing Providence not only at National Poetry Slam, but at the Individual World Poetry Slam in Spokane, Washington, in September. -

Skaldic Slam: Performance Poetry in the Norwegian Royal Court

Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Skaldic Slam: Performance Poetry in the Norwegian Royal Court Anna Millward Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands December 2014 Norrænn trú Félags- og mannvísindadeild 1 Anna Millward MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis MA Kennitala: 150690-3749 Winter 2014 DEDICATION AND DISCLAIMER I owe special thanks to Prof. Terry Gunnell for his continued encouragement, help and enthusiasm throughout the process of researching and writing this dissertation. Many of the ideas put forward in this dissertation are borne out of interesting conversations and discussions with Prof. Gunnell, whose own work inspired me to take up this subject in the first place. It is through Prof. Gunnell’s unwavering support that this thesis came into being and, needless to say, any mistakes or errors are mine entirely. Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Anna Millward, 2014 Reykjavík, Ísland 2014 2 Anna Millward MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis MA Kennitala: 150690-3749 Winter 2014 CONTENTS Introduction pp. 5-13 Chapter 1. Skálds, Scholar, and the Problem of the Pen 1.1. What is Skaldic Poetry? pp. 14-15 1.2. Form and Function pp. 15-22 1.3. Preservation Context pp. 22-24 1.4. Scholarly Approaches to Skaldic Verse p. 25 1.5. Skaldic Scholarship: post-1970s pp. 26-31 1.6. Early Skaldic Scholarship: pre-1970s pp. 31-36 1.7. Skaldic as Oral Poetry, Oral Poetry as Performance pp. 36-43 1.8. -

436320 1 En Bookbackmatter 189..209

BIBLIOGRAPHY Adorno, Theodor & Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Translated by E. Jephcott, Stanford University Press, 2002. Allen, Tim & Andrew Duncan (eds.). Don’t Start Me Talking: interviews with contemporary poets. Salt, 2006. Alvarez, Al (ed.). The New Poetry. Penguin, 1966. Allnut, Gillian et al (eds). The New British Poetry. Paladin, 1988. Anderson, Simon. “Fluxus, Fluxion, Fluxshoe: the 1970s”. The Fluxus Reader, edited by Ken Friedman. Academy Editions, 1998, pp. 22–30. Andrews, Malcom. Charles Dickens and his performing selves: Dickens and public readings. Oxford University Press, 2006. Artaud, Antonin. Selected Writings, edited by Susan Sontag. Strauss & Giroux, 1976 Auslander, Philip. “On the Performativity of Performance Documentation”. After the Act—The (Re)Presentation of Performance Art, edited by Barbara Clausen. Museum Moderner Kunt Stiftung Ludwig Wien, 2005, pp. 21–33. Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words: the William Harvey James lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Claredon Press, 1975. Badiou, Alain. Being and Event. Translated by O. Feltman, Continuum, 2007. Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Translated by L. Burchill, Indiana University Press, 1984. Barry, Peter. “Allen Fisher and ‘content-specific’ poetry”. New British Poetries: The Scope of the Possible, edited by Robert Hampson & Peter Barry. Manchester University Press, 1993, pp. 198–215. ———. Contemporary British Poetry and the City. Manchester University Press, 2000. ———. Poetry Wars: British poetry of the 1970s and the battle for Earl’s Court. Salt, 2006. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 189 J. Virtanen, Poetry and Performance During the British Poetry Revival 1960–1980, Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-58211-5 190 BIBLIOGRAPHY Blanc, Alberto C.