Listening to the Line: Notes on Music, Globalization, and the US-Mexico Border1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josh Norek and Juan Manuel Caipo Join Onerpm; Company Establishes San Francisco Office

Josh Norek and Juan Manuel Caipo Join ONErpm; Company Establishes San Francisco Office San Francisco, CA, October 29, 2018 – Label services, rights management and distribution company ONErpm has announced the addition of Josh Norek as Director, San Francisco & U.S. Latin and Juan Manuel Caipo, A&R, North America & U.S. Latin, to the team. Their hires also mark the establishment of ONErpm’s first West Coast office, in San Francisco. This is the company’s fourth U.S. location, along with Brooklyn, Miami, and Nashville. (For hi-res version, click here: Norek, Caipo) “Josh and Juan Manuel have incredible credentials that I am certain will present new perspectives and possibilities for the growth of ONErpm in North America,” said Jason Jordan, Managing Director of US Operations. “Their varied experiences will help us maximize our catalog and artist opportunities across platforms and establish our West Coast presence.” “I am excited to be working with ONErpm founder Emmanuel Zunz and with Jason Jordan, whose visions for the future of distribution and business intelligence resonate with my own,” said Norek. “Their Latin music program is already so strong, and I’m looking forward to growing that as well as supporting ONErpm’s work in other genres.” “I believe ONErpm is changing how musicians can approach releasing their music, and I look forward to seeing what relationships we can build with artists to help them reach global audience,” said Caipo. Josh Norek has been immersed in many aspects of the Latin music industry for over twenty years. He founded and continues to serve as the president of the music royalties collection firm Regalías Digitales. -

At Home Worship Kit 24

Border wall mural that reads, “There are dreams on this side too.” CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH OF LA JOLLA AUGUST 23, 2020 HOME WORSHIP GUIDE 24 WELCOME TO WEEK 24 OF THE CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH OF LA JOLLA´S AT HOME WORSHIP EXPERIENCE. PLEASE FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS IN THIS GUIDE AND UTILIZE THE AUDIO LINKS SENT TO YOU IN THE ACCOMPANYING EMAIL TO ASSIST IN YOUR WORSHIP EXPERIENCE. PLEASE PROVIDE US WITH FEEDBACK IF YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS OR CONCERNS. YOU CAN REACH US AT [email protected]. THIS IS CHURCH. THIS IS HOLY. THIS IS HOW WE RESPOND TO THE CHALLENGES OF OUR DAY. THIS WILL BE VERY MUCH UNLIKE WHAT YOU ARE USED TO IN CHURCH. THAT IS ON PURPOSE. THIS IS SOMETHING NEW AND BECAUSE OF THAT WE’VE TAKEN LIBERTIES TO PROVIDE YOU WITH SOMETHING TOTALLY DIFFERENT. ENJOY MUSICAL SELECTIONS YOU MIGHT NOT HAVE HEARD AT CHURCH BEFORE AND A MESSAGE UNLIKE THAT WHICH IS DELIVERED FROM THE PULPIT. CONSIDER IT AN ADVENTURE. YES, YOU ARE MAKING HISTORY TODAY. PLEASE FIND A COMFORTABLE AND COMFORTING PLACE IN YOUR HOME OR SOMEWHERE ELSE YOU FEEL SAFE. GET COMFORTABLE, POUR YOURSELF A GLASS OF SOMETHING SOOTHING AND ENJOY THIS EXPERIMENT IN WORSHIP…. WE PREPARE OUR HEARTS AND MINDS FOR WORSHIP ENJOY NINA’S PIANO SOLO BY CLICKING THE AUDIO FILE MARKED “AUDIO FILE 1” IN THE EMAIL. DURING THIS TIME LEAVE YOUR FEARS, DOUBTS, AND UNCERTAINTIES OUTSIDE THE ROOM AND BE COMPLETELY PRESENT WITH YOURSELF. BREATHE INTENTIONALLY AND FOCUS ON EACH INHALE AND EXHALE Mural in downtown Tijuana, Baja California FINDING GOD IN VOICE ENJOY BRONWYN’S SOLO BY CLICKING ON THE AUDIO FILE MARKED “AUDIO FILE 2” IN THE EMAIL. -

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio Musical Urbano? Su Permanencia En Tijuana Y Sus Transformaciones Durante La Guerra Contra Las Drogas: 2006-2016

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio musical urbano? Su permanencia en Tijuana y sus transformaciones durante la guerra contra las drogas: 2006-2016. Tesis presentada por Pedro Gilberto Pacheco López. Para obtener el grado de MAESTRO EN ESTUDIOS CULTURALES Tijuana, B. C., México 2016 CONSTANCIA DE APROBACIÓN Director de Tesis: Dr. Miguel Olmos Aguilera. Aprobada por el Jurado Examinador: 1. 2. 3. Obviamente a Gilberto y a Roselia: Mi agradecimiento eterno y mayor cariño. A Tania: Porque tú sacrificio lo llevo en mi corazón. Agradecimientos: Al apoyo económico recibido por CONACYT y a El Colef por la preparación recibida. A Adán y Janet por su amistad y por al apoyo desde el inicio y hasta este último momento que cortaron la luz de mi casa. Los vamos a extrañar. A los músicos que me regalaron su tiempo, que me abrieron sus hogares, y confiaron sus recuerdos: Fernando, Rosy, Ángel, Ramón, Beto, Gerardo, Alejandro, Jorge, Alejandro, Taco y Eduardo. Eta tesis no existiría sin ustedes, los recordaré con gran afecto. Resumen. La presente tesis de investigación se inserta dentro de los debates contemporáneos sobre cultura urbana en la frontera norte de México y se resume en tres grandes premisas: la primera es que el corrido y el metal forman parte de dos estructuras musicales de larga duración y cambio lento cuya permanencia es una forma de patrimonio cultural. Para desarrollar esta premisa se elabora una reconstrucción historiográfica desde la irrupción de los géneros musicales en el siglo XIX, pasando a la apropiación por compositores tijuanenses a mediados del siglo XX, hasta llegar al testimonio de primera mano de los músicos contemporáneos. -

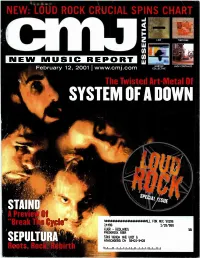

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia | Norient.Com 7 Oct 2021 06:12:57

Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 06:12:57 Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia by Moses Iten Since the beginning of the 21st century «new wave cumbia» has been growing as an independent club culture simultaneously in several parts of the world. Innovative producers have reinvented the dance music-style cumbia and thus produced countless new subgenres. The common ground: they mix traditional Latin American cumbia-rhythms with rough electronic sounds. An insider perspective on a rapid evolution. From the Norient book Out of the Absurdity of Life (see and order here). https://norient.com/stories/new-wave-cumbia Page 1 of 15 Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 06:12:58 Dreams are made of being at the right place at the right time and in early June 2007 I happened to arrive in Tijuana, Mexico. Tijuana had been proclaimed a new cultural Mecca by the US magazine Newsweek, largely due to the output of a group of artists called Nortec Collective and inadvertently spawned a new scene – a movement – called nor-tec (Mexican norteno folk music and techno). In 2001, the release of the compilation album Nortec Collective: The Tijuana Sessions Vol.1 (Palm Pictures) catapulted Tijuana from its reputation of being a sleazy, drug-crime infested Mexico/US border town to the frontline of hipness. Instantly it was hailed as a laboratory for artists exploring the clash of worlds: haves and have-nots, consumption and its leftovers, South meeting North, developed vs. underdeveloped nations, technology vs. folklore. After having hosted some of the first parties in Australia featuring members of the Nortec Collective back in 2005 and 2006, the connection was made. -

Marlboro MX Beat 2009

Contact information for specific bands and more details below Festival: Tobacco Sponsor: PMI Websites: Other info: Annual concert series sponsored by Marlboro: attracts independent rock Marlboro MX Mexico Subsidiary than manufactures Event site bans (internationally) and local acts for a variety of music. Beat 2009 Marlboro: Cigarros La Tabacalera https://www.m Mexicana SA de CV (CIGATAM) arlboro.com.m Each city has a different play bill CONTACT: Manuel Salazar 132, Col x/ Providencia, Mexico DF, 02440, Mexico Line up +52 (55) 5267 6208 (Phone) Adult concert +52 (55) 5328 3001 (fax) http://thecitylov esyou.com/even “The annual festival sponsored by the tobacco Marlboro has distinguished itself year ts/?p=925 after year to bring bands, that while not necessarily part of the mainstream sound, steadily into the world of pop and independent music.” (roughly translated from: http://radiomedium.blogspot.com/2009/01/mx-beat-2009.html) Location Band Country of Origin Website Charity/ Social Responsibility Other Information/News (Audience) Guadalajara Mystery Jets London, UK http://www.myspace. May 28, 2008: Participated in a English indie band that is rising in popular fame (San Siro com/mysteryjets concert to raise money for cancer /Feb 21) research (proceeds donated to http://en.wikipedia.or the Royal Marsden Hospital and g/wiki/Mystery_Jets No Surrender Charitable Trust) http://www.indielondon.co.uk/Musi c-Review/maximo-park-and- mystery-jets-to-play-charity- london-show-2008 Sebastien Teller Paris, France http://www.recordmak Electronic Indie ers.com/ Golden Silvers London, UK http://goldensilvers.co Formed in 2007 .uk/ Ghostland Austin, Texas, USA http://en.wikipedia.or American indie, electro rock band Observatory g/wiki/Ghostland_Ob Appeared on Conan O’Brian Oct 2007 servatory http://www.trashymop ed.com/ Danger France http://www.myspace. -

Five Video Clips from Mexico | Norient.Com 4 Oct 2021 10:31:32 Five Video Clips from Mexico PLAYLIST by Moses Iten

Five Video Clips from Mexico | norient.com 4 Oct 2021 10:31:32 Five Video Clips from Mexico PLAYLIST by Moses Iten In our video clip series we're heading for Mexico this time. Australian author Moses Iten compiled five Mexican clips for Norient between field recordings, Reggaeton and Cumbia. He begins with one of our long time favorites, a sci-fi shaving odyssey starting from the heights of Machu Picchu. But see and read by yourself what he's got for you furthermore. Artist: Frikstailers Track: Crop Circles The team behind this video is Flamboyant Paradise, who really brought the Frikstailers to worldwide attention with their remix of «Hold The Line» by Major Lazer. The Frikstailers duo is originally from Cordoba, Argentina, but in recent years have relocated to the world’s largest metropolis: Mexico City. Their irreverent sense of humour and fun approach to dancefloor music is reflected in their visuals, whilst at the same time a profound commentary on «Latin American» identity, both exploiting and playing with clichés. Artist: Nortec Collective Presents: Bostich+Fussible Track: Camino Verde Nortec Collective have always produced outstanding videos, because is characterized by musicians and video artists work in constant collaboration both conceptually and aesthetically. Both Bostich and Fussible live in the Las Playas neighbourhood where this video was filmed, and another characteristic of their videos are the many personal references made and being in tribute to their beloved city of Tijuana. Bostich+Fussible imagine «Camino Verde» as the name of an imaginary underground metro line in Tijuana, a city well known for it’s lack of civic infrastructure. -

Nuestros Cuerpos Son Los Paísesde Este Poderosos

4D EXPRESO Jueves 13 de Diciembre de 2007 eSTELAR NORTEÑOEXPRESO TE INVITA -TECH Nortec ofrecerá MIEMBROS concierto en Expo DE LA BANDA Fórum el próximo ◗ Fusible (Pepe Mogt) domingo ◗ Bostich (Ramón Amescua) ◗ Panóptica (Roberto Mendoza) ◗ / EXPRESO Archivo Por Enrique de la Vega Clorofila (Jorge Verdín) El colectivo ofrecerá su ‘show’ completo en Hermosillo el próximo ◗ [email protected] Hiperboreal (P.G. Beas) domingo. COLABORADOR Luces, música, humo, baile, imá- genes, ambiente, frescura, y so- LOS OCHO bre todo energía, son las carac- DISCOGRAFÍA terísticas con las que se puede ◗ Nortec Sampler (1999) Instrumentos con los cuales describir a Nortec, una forma de ◗ Tijuana Sessions Vol. 1 (2001) trabaja Nortec ver más allá de la música y de- ◗ Tijuana Sessions Vol. 2 (2005) mostrar que en México se pueden ◗ Tijuana Sessions Vol. 3 (2005) realizar buenas e innovadoras 1 Bajos acústicos 5Líneas de tarolas polirítmicas propuestas musicales. Colectivo Nortec es una agru- 2Metales 6Bajo sexto pación formada por diferentes SOUNDTRACKS 3 7 proyectos individuales que for- ◗ FIFA 2006 Tubas Acordeón man esta música. Y su nombre ◗ Efectos Secundarios 4 8 viene de norteño y techno, junto ◗ Una Película de Huevos Bombos resonantes Cajas de ritmos y sintetizadores con la convergencia de high-tech ◗ Niptuk (serie estadounidense) y low-tech, pero sobre todo es la ◗ FIFA 2005 combinación de la música elec- trónica con la cultura del género nor teño, acompa ñ ad a de l a ba nd a La única condición que había sinaloense. para experimentar con los soni- dos era que estas pistas fueran la ¡NO ¿Cómo nacen? base para crear una pieza nueva; TE LO PIERDAS! El sonido de Nortec comenzó a varios músicos locales partici- ◗ fi nales del siglo pasado, cuando paron en la convocatoria, y así Cuándo: 16 de diciembre ◗ Pepe Mogt se cansó de seguir se formó Nortec. -

Five Video Clips from Mexico | Norient.Com 5 Oct 2021 19:23:12 Five Video Clips from Mexico PLAYLIST by Moses Iten

Five Video Clips from Mexico | norient.com 5 Oct 2021 19:23:12 Five Video Clips from Mexico PLAYLIST by Moses Iten In our video clip series we're heading for Mexico this time. Australian author Moses Iten compiled five Mexican clips for Norient between field recordings, Reggaeton and Cumbia. He begins with one of our long time favorites, a sci-fi shaving odyssey starting from the heights of Machu Picchu. But see and read by yourself what he's got for you furthermore. Artist: Frikstailers Track: Crop Circles The team behind this video is Flamboyant Paradise, who really brought the Frikstailers to worldwide attention with their remix of «Hold The Line» by Major Lazer. The Frikstailers duo is originally from Cordoba, Argentina, but in recent years have relocated to the world’s largest metropolis: Mexico City. Their irreverent sense of humour and fun approach to dancefloor music is reflected in their visuals, whilst at the same time a profound commentary on «Latin American» identity, both exploiting and playing with clichés. Artist: Nortec Collective Presents: Bostich+Fussible Track: Camino Verde Nortec Collective have always produced outstanding videos, because is characterized by musicians and video artists work in constant collaboration both conceptually and aesthetically. Both Bostich and Fussible live in the Las Playas neighbourhood where this video was filmed, and another characteristic of their videos are the many personal references made and being in tribute to their beloved city of Tijuana. Bostich+Fussible imagine «Camino Verde» as the name of an imaginary underground metro line in Tijuana, a city well known for it’s lack of civic infrastructure. -

The Son Jarocho Revival: Reinvention and Community Building in a Mexican Music Scene in New York City

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 The Son Jarocho Revival: Reinvention and Community Building in a Mexican Music Scene in New York City Emily J. Williamson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2673 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SON JAROCHO REVIVAL: REINVENTION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING IN A MEXICAN MUSIC SCENE IN NEW YORK CITY by EMILY J. WILLIAMSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 EMILY WILLIAMSON All Rights Reserved ii THE SON JAROCHO REVIVAL: REINVENTION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING IN A MEXICAN MUSIC SCENE IN NEW YORK CITY by EMILY J. WILLIAMSON This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music to satisfy the dissertation Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ ___________________________________ Date Jonathan Shannon Chair of Examining Committee ________________ ___________________________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Peter Manuel Jane Sugarman Alyshia Gálvez THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Son Jarocho Revival: Reinvention and Community Building in a Mexican Music Scene in New York City by Emily J. Williamson Advisor: Peter Manuel This dissertation analyzes the ways son jarocho (the Mexican regional music, dance, and poetic tradition) and the fandango (the son jarocho communitarian musical celebration), have been used as community-building tools among Mexican and non-Mexican musicians in New York City. -

Alejandro L. Madrid. 2008. Nor-Tee Rifa!: Electronic Dance Music from Tijuana to the World

Alejandro L. Madrid. 2008. Nor-tee Rifa!: Electronic Dance Music from Tijuana to the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reviewed by Gavin Mueller The burgeoning field of electronic dance music (EDM) scholarship has drawn from a number of theoretical and methodological perspectives. In particular, the disciplinary melange that is cultural studies, whose rise in academia coincided with EDM's rise in popular music during the 1980s and '90s, has proven an effective tool for researchers seeking to understand the social worlds and political and economic contexts in which EDM sounds and styles arise. Alejandro L. Madrid's Nor-tee Rita! is one such effort, a sorely needed piece of research in a non-Western EDM scene, when academia in general has lagged behind popular publications and blogs in the documenta tion and analysis of global EDM. The book's purported object of analysis-a Tijuana-based scene knit together through aesthetic practices rooted in the appropriation of the sounds and images of northern Mexico-is appropriately conceptualized for a cultural studies approach. Furthermore, as an ethnomusicologist familiar with cultural theory, Madrid can undergird arguments rooted in post-structuralist theories with solid ethnographic data drawn from participant observation among artists and fans. In the author's words, this is "primarily a book about borders" (3), and these borders are a poten tially rich site of investigation, since the music's home base of Tijuana is nestled between worlds, while the "heterogeneous music whose styles are as diverse as the number of musicians, producers, and DJs that compose it" (9) nudges up against several genres of EDM. -

La Norteña: Una Historia Desde Los Dos Lados Del Río

Historia de la música norteña mexicana LUIS DÍAZ SANTANA GARZA, 2016 Plaza y Valdés, México La norteña: una historia desde los dos lados del río JOSÉ JUAN OLVERA GUDIÑO uando observo el auge en México de ciertas músicas populares Cen nuestra vida cotidiana, me viene a la mente la palabra “nor- teñización”. Este concepto fue acuñado en 1998 por Rafael Alarcón pa- ra estudiar el impacto de la migración internacional en la población de Chavinda, Michoacán. Desde 2009, he propuesto el concepto “norte- ñización musical de México” para designar esta especie de hegemo- La norteña: A Story from nía de las culturas musicales del Norte del país —música norteña de both Sides of the River acordeón y bajo sexto, música de banda, movimiento alterado, la mú- sica nortec, parte de la llamada música grupera, etc.—, en cada vez JOSÉ JUAN OLVERA GUDIÑO más espacios sociales, presenciales o virtuales, nacionales o transnacio- Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios nales. Esta hegemonía es expresión de la fuerza económica e ideológica Superiores en Antropología Social-Noreste, que se ha desarrollado en los estados del Norte de México durante el Monterrey, Nuevo León, México [email protected] último medio siglo. Lo anterior me lleva a refexionar sobre la actitud de nuestras es- cuelas y facultades de música ante este fenómeno: indolente, por decir lo menos; soberbia, si uno quisiera pelea. Centradas en sus programas Desacatos 58, tradicionales, que acentúan la formación clásica o cuando mucho in- septiembre-diciembre 2018, pp. 204-208 cluyen el estudio de algunas músicas tradicionales, ignoran casi por 204 Desacatos 58 José Juan Olvera Gudiño completo las emergencias que ocurren en la música Rangel (2016), que analiza el papel de la música y la popular, sus motivos, limitaciones o potencialida- festa en una comunidad de Los Ramones, Nuevo des, en fn, su papel en la vida de las personas.