Sri Lanka June 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparatory Survey Report on Rehabilitation of Kilinochchi Water Supply Scheme in Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE NATIONAL WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE BOARD (NWSDB) PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON REHABILITATION OF KILINOCHCHI WATER SUPPLY SCHEME IN DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA DECEMBER 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) NJS CONSULTANTS CO.,LTD GED JR 11-191 The cost estimates is based on the price level and exchange rate of June 2011. The exchange rate is: Sri Lanka Rupee 1.00 = Japanese Yen 0.749 (= US$0.00897) DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE NATIONAL WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE BOARD (NWSDB) PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON REHABILITATION OF KILINOCHCHI WATER SUPPLY SCHEME IN DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA DECEMBER 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) NJS CONSULTANTS CO.,LTD Preface Japan International cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct ‘The Preparatory Survey on Rehabilitation of Killinochchi Water Supply Scheme in Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka”, and organized a survey team, NJS Consultants Co., Ltd. between February, 2011 to December, 2011. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Sri Lanka, and conducted a field investigation. As a result of further studies in Japan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will continue to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement to the friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Sri Lanka for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. December, 2011 Shinya Ejima Director General Global Environment Department Japan International Cooperation Agency Summary 1. -

Project for Formulation of Greater Kandy Urban Plan (Gkup)

Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute EI ALMEC Corporation JR 18-095 Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute ALMEC Corporation Currency Exchange Rate September 2018 LKR 1 : 0.69 Yen USD 1 : 111.40 Yen USD 1 : 160.83 LKR Map of Greater Kandy Area Map of Centre Area of Kandy City THE PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PART 1: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Objective and Outputs of the Project ....................................................... 1-2 1.3 Project Area ............................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 Implementation Organization Structure ................................................... -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Sri Lanka Anketell Final

The Silence of Sri Lanka’s Tamil Leaders on Accountability for War Crimes: Self- Preservation or Indifference? Niran Anketell 11 May 2011 A ‘wikileaked’ cable of 15 January 2010 penned by Patricia Butenis, U.S Ambassador to Sri Lanka, entitled ‘SRI LANKA WAR-CRIMES ACCOUNTABILITY: THE TAMIL PERSPECTIVE’, suggested that Tamils within Sri Lanka are more concerned about economic and social issues and political reform than about pursuing accountability for war crimes. She also said that there was an ‘obvious split’ between diaspora Tamils and Tamils within Sri Lanka on how and when to address the issue of accountability. Tamil political leaders for their part, notably those from the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), had made no public remarks on the issue of accountability until 18 April 2011, when they welcomed the UN Secretary-General’s Expert Panel report on accountability in Sri Lanka. That silence was observed by some as an indication that Tamils in Sri Lanka have not prioritised the pursuit of accountability to the degree that their diaspora counterparts have. At a panel discussion on Sri Lanka held on 10 February 2011 in Washington D.C., former Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, Donald Camp, cited the Butenis cable to argue that the United States should shift its focus from one of pursuing accountability for war abuses to ‘constructive engagement’ with the Rajapakse regime. Camp is not alone. There is significant support within the centres of power in the West that a policy of engagement with Colombo is a better option than threatening it with war crimes investigations and prosecutions. -

Preparedness for Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals

Preparedness for Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals Report No.PER/2017/2018/SDG/05 National Audit Office Performance Audit Division 1 | P a g e National preparedness for SDG implementation The summary of main observations on National Preparedness for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is as follows. 1. The Rapid Integrated Assesment (RIA) is a first step in the process of aligning the country,s national development plan or public Investment programme with SDGs and RIA reveals an uneven alignment between the policy initiatives in the 2017 -2020 Public Investment Programme and the SDG target areas for the economy as (84%) people (80%) planet (58%) peace (42%) and partnership (38%). 2. After deducting debt repayments, the Government has allocated Rs. 440,787 million or 18 percent out of the total national budget of Rs. 2,997,845 million on major projects which identified major targets of relevant SDGs in the year 2018. 3. Sri Lanka had not developed a proper communication strategy on monitoring, follow up, review and reporting on progress towards the implementation of the 2030 agenda. 2 | P a g e Audit at a glance The information gathered from the selected participatory Government institutions have been quantified as follows. Accordingly, Sri Lanka has to pay more attention on almost all of the areas mentioned in the graph for successful implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. 40.0% Alignment of budgets, policies 34.5% and programmes 35.0% Policy integration and coordination 30.0% 28.5% 28.3% 27.0% 26.6% Creating ownership and engaging stakeholders 25.0% 24.0% Identification of resources and 20.5% 21.0% capacities 20.0% Mobilizing partnerships 15.0% Managing risks 10.0% Responsibilities, mechanism and process of monitoring, follow-up 5.0% etc (institutional level) Performance indicators and data 0.0% 3 | P a g e Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ -

Environmental Assessment Report Sri Lanka

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination – Provincial Roads Component: Mannar–Vavuniya District Project Number: 42254 May 2010 Sri Lanka: Northern Road Connectivity Project Prepared by [Author(s)] [Firm] [City, Country] Prepared by the Ministry of Local Govern ment and Provincial Councils for th e Asian Development Bank (ADB). Prepared for [Executing Agency] [Implementi ng Agency] The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of AD B’s Board of Di rectors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s in nature. members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank BIQ - Basic Information Questionnaire CCD - Coast Conservation Department CEA - Central Environmental Authority CEB - Ceylon Electricity Board CSC - Consultant Supervision Consultant DBST - Double Bituminous Surface Treatment DCS - Department of Census and Statistics DoF - Department of Forestry DoI - Department of Irrigation DoS - Department of Survey DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division DWLC - Department of Wild Life Conservation EA - Executive Agency EMP - Environmental Management Plan EMo - Environmental Monitoring Plan EPL - Environment Protection Liaison ESCM - Environmental Safeguards Compliance Manual GND - Grama Niladhari Division GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GSMB - Geological -

Annual Performance Report of the District Secretariat

ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE 뷒ස්ත්රි槊 ලේක කායාලය,ක臊ල臊ය,ි槔ණාමලය khtl;lr; nrayfk;, jpUNfhzkiy District Secretariat, Kachcheri, Trincomalee වාික කායස්ත්ාධන වාතාව tUlhe;j nraw;jpwd; mwpf;if ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2019 0 ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE Annual Performance Report for the year 2019 District Secretariat, Trincomalee Expenditure Head No 271 Contents Page Chapter 01 - Institutional Profile ………………………………………………………… 2-10 Chapter 02 – Progress and the Future Outlook …………………………………... 11 Chapter 03 - Overall Financial Performance for the Year ……………….……. 12-41 Chapter 04- Performance of the achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) ………………………………………………. 42-45 Chapter 05 - Human Resource Profile ………………………………………………… 46-48 Chapter 06– Compliance Report ………………………………………………………… 49-54 1 ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE Chapter 01 - Institutional Profile 1.1. Introduction Trincomalee District - A Glimpse The Boundary Trincomalee, a picturesque city with a natural 2arbor, scenic beauty, and military, commercial and historical importance, is situated in the eastern coast of Sri Lanka. Trincomalee District is boarded with Mulathivu District in North, Anuradhapura District in West and Polonnaruwa and Batticaloa Districts in the South. The History The history of Trincomalee goes back to a time of immemorial. The Mahavamsa & Chulavamsa, the two great chronicles, mention present Trincomalee as “Gokanna” , Gokarna, and “Gonagamaka” During the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods of island’s history. The Administration The Trincomalee District located in the center of Eastern Province covering an area of 2,727 square kilometers. The district is divided into 11 Divisional Secretary’s Divisions for administrative purpose. The DS Divisions are further sub-divided into 230 Grama Niladhari Divisions. -

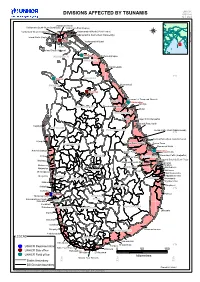

DIVISIONS AFFECTED by TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka

UNHCR DIVISIONS AFFECTED BY TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka ValikamamValikamam NorthNorth ValikamamValikamam South-WestSouth-West (Sandilipay)(Sandilipay) ValikamamValikamam EastEast (Kopay)(Kopay) Valikamam West (Chankanai) VadamaradchiVadamaradchi NorthNorth (Point(Point Perdro)Perdro) JAFFNAJAFFNA VadamaradchiVadamaradchi South-WestSouth-West (Karaveddy)(Karaveddy) Island North (Kayts) JaffnaJaffna VadamaradchiVadamaradchi EastEast Divisions.WOR Affected Jaffna DelftDelft DelftDelftIsland South (Velanai) KillinochchiKillinochchi KILINOCHCHIKILINOCHCHI KillinochchiKillinochchi PuthukudiyiruppuPuthukudiyiruppu MULLAITIVUMULLAITIVU MaritimepattuMaritimepattu 9°N MannarMannar VAVUNIYAVAVUNIYA MANNARMANNAR KuchchaveliKuchchaveli VavuniyaVavuniya TrincomaleeTrincomalee TownTown andand GravetsGravets MorawewaMorawewa TrincomaleeTrincomalee KinniyaKinniya ANURADHAPURAANURADHAPURA ThambalagamuwaThambalagamuwa MutturMuttur TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE SeruvilaSeruvila Verugal/Verugal/ EchchilampattaiEchchilampattai KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu NorthNorth KalpitiyaKalpitiya PUTTALAMPUTTALAM POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Oddamavadi)(Oddamavadi) 8°N KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Valachchenai)(Valachchenai) MundelMundel KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown KURUNEGALAKURUNEGALA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown ManmunaiManmunai NorthNorth ArachchikattuwaArachchikattuwa BatticaloaBatticaloa EravurEravur PattuPattu BatticaloaBatticaloaKattankudyKattankudy ManmunaiManmunai -

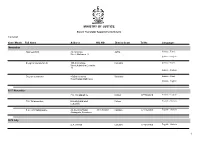

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Trincomalee District – 2007

BASIC POPULATION INFORMATION ON TRINCOMALEE DISTRICT – 2007 Preliminary Report Based on Special Enumeration – 2007 Department of Census and Statistics October 2007 ISBN 978-955-577-616-5 Foreword The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), carried out a special enumeration in Eastern province and in Jaffna district in Northern province. The objective of this enumeration is to provide the necessary basic information needed to formulate development programmes and relief activities for the people. This preliminary publication for Trincomalee district has been compiled from the reports obtained from the District based on summaries prepared by enumerators and supervisors. A final detailed information will be disseminated after the computer processing of questionnaires. This preliminary release gives some basic information for Trincomalee district, such as population by divisional secretary’s division, urban/rural population, sex, age (under 18 years and 18 years and over) and ethnicity. Data on displaced persons due to conflict or tsunami are also included. Some important information which is useful for regional level planning purposes are given by Grama Niladhari Divisions. This enumeration is based on the usual residents of households in the district. These figures should be regarded as provisional. I wish to express my sincere thanks to the staff of the department and all other government officials and others who worked with dedication and diligence for the successful completion of the enumeration. I am also grateful to the general public for extending their fullest co‐operation in this important undertaking. This publication has been prepared by Population Census Division of this Department. D.B.P. Suranjana Vidyaratne Director General of Census and Statistics 10th October 2007 Department of Census and Statistics, 15/12, Maitland Crescent, Colombo 7. -

Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL)* **

A/HRC/30/CRP.2 Advance Version Distr.: Restricted 16 September 2015 English only Human Rights Council Thirtieth session Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL)* ** * Reproduced as received ** The information contained in this document should be read in conjunction with the report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights- Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka (A/HRC/30/61). A/HRC/30/CRP.2 Contents Paragraphs Page Part 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–13 5 II. Establishment of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), mandate and methodology ............................................................................................................. 14–46 7 III. Contextual background ........................................................................................... 47–103 12 IV. Overview of Government, LTTE and other armed groups...................................... 104–170 22 V. Legal framework ..................................................................................................... 171–208 36 Part 2– Thematic Chapters VI. Unlawful killings ..................................................................................................... 209–325 47 VII. Violations related to the -

Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 51–70 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.145 Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society Kalinga Tudor Silva1 Abstract More than a decade after the end of the 26-year old LTTE—led civil war in Sri Lanka, a particular section of the Jaffna society continues to stay as Internally Displaced People (IDP). This paper tries to unravel why some low caste groups have failed to end their displacement and move out of the camps while everybody else has moved on to become a settled population regardless of the limitations they experience in the post-war era. Using both quantitative and qualitative data from the affected communities the paper argues that ethnic-biases and ‘caste-blindness’ of state policies, as well as Sinhala and Tamil politicians largely informed by rival nationalist perspectives are among the underlying causes of the prolonged IDP problem in the Jaffna Peninsula. In search of an appropriate solution to the intractable IDP problem, the author calls for an increased participation of these subaltern caste groups in political decision making and policy dialogues, release of land in high security zones for the affected IDPs wherever possible, and provision of adequate incentives for remaining people to move to alternative locations arranged by the state in consultation with IDPs themselves and members of neighbouring communities where they cannot be relocated at their original sites. Keywords Caste, caste-blindness, ethnicity, nationalism, social class, IDPs, Panchamars, Sri Lanka 1Department of Sociology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] © 2020 Kalinga Tudor Silva.