Towards Resilient Social Dialogue in South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applications Received During 1 to 28 February, 2019

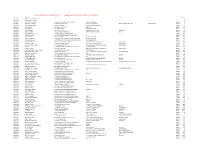

Applications received during 1 to 28 February, 2019 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 28 February, 2019. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 1599/2019-CO/SW 01-02-2019 Play My Opinion ( i Phone Application) Computer Software Sanjay K Gupta 2 1600/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 Black Literary/ Dramatic Hema Mathy Bernatsha 3 1601/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 CAMP Literary/ Dramatic VISHNU IS 4 1602/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 LAB MANUAL DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF Literary/ Dramatic BHUSHAN BAWANKAR, Dr. M. M.Raghuwanshi ALGORITHM 5 1606/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 GANIT CLASS 9 Literary/ Dramatic VIDYA PRAKASHAN MANDIR PVT LTD 6 1607/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 GANIT CLASS 10 Literary/ Dramatic VIDYA PRAKASHAN MANDIR PVT LTD 7 1608/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 SALONWAALE Literary/ Dramatic TRUNK LORD TECHNOLOGIES PRIVATE LIMITED 8 1609/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 GANIT CLASS 11 Literary/ Dramatic VIDYA PRAKASHAN MANDIR PVT LTD 9 1610/2019-CO/L 01-02-2019 GANIT 12 Literary/ Dramatic VIDYA PRAKASHAN MANDIR PVT LTD 10 1611/2019-CO/A 01-02-2019 BLACK GOLD (BLACK HENNA) Artistic ASHOK KUMAR SETHI, TRADING AS: ABHINAV EXPORT CORPORATION. -

Form IEPF-2 2014-15

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L74899DL1985PLC021445 Prefill Company/Bank Name SELAN EXPLORATION TECHNOLOGY LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 12-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1616280.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) VIJAY G DAVE SH GUNVANT RAIDAVESERVICE C O G A Dave Advocate Near Govt HospitalINDIA Muli Surendra NagarGujarat Dist Gujrat 363510 S00000041 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend2750.00 07-MAR-2022 KIRAN R DAVE SH RAJESH GDAVEHOUSEHOLD C O G A Dave Advocate Near Govt HospitalINDIA Muli Surendra NagarGujarat Dist Gujrat 363510 S00000042 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend2750.00 07-MAR-2022 NITIN RAJMAL DESAI SH RAJMAL KDESAIBUSINESS Land Markt E 3 103 Poonam Nagar MahakaliINDIA Road Andheri MaharashtraEast -

GIPE-208819-Contents.Pdf (10.25Mb)

THE BOOK At the Census of India, in 1881, an attempt was lll3de to obtain the materials for a complete list of all Castes and Tribes as 1 eturned by the. people themselves .and ente red by the Census Enumerators in their Schedutes. Instructions were sent to .each Province and Native State directing that the number of each Caste recorded, .and the composition of each Caste by sex should be shown in the .:final report. In this manner it was designed to lay "a foundation for further research into the little l-nown subject of Caste," a subject .in inquiring into which investigators have been gravelled, not for lack of matter but from its abundance and complexity, and the lack of all rational arran~ment. The subject as a whole has indeed been a mighty maze without a plan. An inquirer .into the social habits and customs of a Caste in nne district h.a.s always been liable to the .subse quent dis.covery that the people whom he had met were but offshoots or wanderers from a larger Tribe whose home was in another province. The distinctive habits and customs of a people are of course always freshest and most marked where the mass of that people dwell : and when a detachment wanders away or splits off from the parent Tribe and settles elsewhere, it suffers, notwithstanding its Caste-conserv ancy. a certain change through the moul ding influence of superior numbers around. Hence the desideratum of a bird'.s-eye view of the entire system of Castes and Tribes found in India : and this, as far as tlteir strength and distribution go, is what 1 have tried to supply in this Compendium. -

The Details of Shareholders Whose Dividend for the Financial Year Shares Are Liable to Be Transferred to Investor Education

The details of Shareholders whose dividend for the Financial Year 2009-10 onwards are unclaimed and their shares are liable to be transferred to Investor Education and Protection Fund Authority ("IEPF Authority") . No. of Shares to S.No. Folio No. / Name(s) of the Shareholder(s) DPID-Client ID be Transferred to IEPF Authority 1 106051201060500019991 AMIT RATHI 40 2 109001201090001031144 JUGAL KISHORE SHARMA 300 3 109001201090001755607 MAHMANDYASIN USMANBHAI MEMAN 1 4 109001201090002563571 MANOJ KUMAR PANDEY 903 5 109001201090002842784 ROSEMARY C . 50 6 109001201090003108847 FAIZAL P K . 20 7 109261201092600026893 KRISHNA MURTHY CHANDRASEKHAR 200 8 113001201130000231968 NEHA JOSHI 50 9 121001201210000076706 CHANDRASHEKAR C. KAMBLE 50 10 121011201210100224581 RAMESHWAR LAL SIYAG 25 11 132001201320000128105 RAJ KUMAR SINHA 100 12 132001201320000673324 SHARADA VEERAPPA FARALASHATTAR 5 13 133001201330000024964 BHAGUBHAI NAGARDAS PRAJAPATI 1 14 158001201580000498216 PRAMOD G SOMKUWAR 12 15 170001201700000054329 BALKRISHNA PATIDAR 100 16 174001301740000083479 G.SURESH . 25 17 175001201750000127831 VIJAY VYANKATRAO RANDHE 100 18 175011201750100046011 VINAYAK GAJANAN PATANKAR 1000 LALITA VINAYAK PATANKAR 19 176001301760000489210 UTTRA SHARMA 100 20 176001301760000691194 RAJ PAL SAHARAN 10 21 186001201860000166030 JYOTHI . 10 22 191011201910100630280 REPALA MURALI 100 23 191011201910100867931 BASAVARAJ CHANABASAYYA MATHAPATI 78 24 191011201910101202172 SATISH CHANDRA VISHNOI 13 25 191011201910101458555 RAVINDRA SINGH 50 26 191031201910300025966 -

Ethnography : Castes and Tribes

िव�ा �सारक मंडळ, ठाणे Title : Ethnography : Caste and Tribes Author : Baines, Athelstane Publisher : Strassburg : Verlang Von Karl J. Trubner Publication Year : 1912 Pages : 231 pgs. गणपुस्त �व�ा �सारत मंडळाच्ा “�ंथाल्” �तल्पा्गर् िनिमर्त गणपुस्क िन�म्ी वषर : 2014 गणपुस्क �मांक : 101 ^ k^ Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde (ENCYCLOPEDIA OF INDO-ARYAN RESEARCH) BEGRUNDET VON G. BUHLER, FORTGESETZT VON F. KIELHORN, HERAUSGEGEBEN VON H. LUDERS UND J. WACKERNAGEL. II. BAND, 5. HEFT. ETHNOGRAPHY (CASTES AND TRIBES) BY SIR ATHELSTANE BAINES WITH A LIST OF THE MORE IMPORTANT WORKS ON INDIAN ETHNOGRAPHY BY W. SIEGLING. ^35^- STRASSBURG VERLAG VON KARL J. TRUBNER 1912. M. DuMout Schauberg, StraCburg. 6RUNDRISS DER INDO-ARISCHEN PHILOLOGIE UND ALTERTUMSKUNDE (ENCYCLOPEDIA OF INDO-ARYAN RESEARCH) BEGRiJNDET VON G. BUHLER, FORTGESETZT VON F. KIELHORN, HERAUSGEGEBEN VON H. LUDERS UND J. WACKERNAGEL. II. BAND, 5. HEFT. ETHNOGRAPHY (CASTES AND TRIBES) BY SIR ATHELSTANE BAINES. INTRODUCTION. § I. The subject with which it is proposed to deal in the present work is that branch of Indian ethnography which is concerned with the social organisation of the population, or the dispersal of the latter into definite groups based upon considerations of race, tribe, blood or oc- cupation. In the main, it takes the form of a descriptive survey of the return of castes and tribes obtained through the Census of 1901. The scope of the review, however, is limited to the population of India properly so called, and does not, therefore, include Burma or the outlying tracts of Baliichistan, Aden and the Andamans, by the omission of which the population dealt with is reduced from 294 to 283 millions. -

Form IEPF-4 2010-11

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the shares transferred to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e‐form IEPF‐4. CIN L74899DL1985PLC021445Prefill Company Name SELAN EXPLORATION TECHNOLOGY LIMITED Nominal value of shares 251960.00 Validate Clear Actual Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id‐Client Id‐ Nominal value of Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Number of shares transfer to IEPF (DD‐ Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number shares MON‐YYYY) SHIVKUMAR BAHL YASHPALL BAHL 34 MAKER CHAMBERS VI 20 NARIMINDIA Maharashtra 400021 SS0000403 22 220 09‐MAY‐2018 SANTABAN PATEL RAMJI PATEL SHRI LAXMI SAW HILL HOSUR HUBLINDIA Karnataka 580021 SS0000506 1364 13640 09‐MAY‐2018 PARAGI YADAV YOGESH YADAV 15 KOYAL GEET VALLABH BAUG GH INDIA Maharashtra 400077 SP0000205 100 1000 09‐MAY‐2018 MAHESH N KOTHARI N KOTHARI 717 STOCK EXCHANGE TOWER DAL INDIA Maharashtra 400023 SM0000250 320 3200 09‐MAY‐2018 JOSEPH DASAN E V NA SELAN EXPLORATION TECHNOLOGYINDIA Delhi Delhi S00009453 10 100 09‐MAY‐2018 AHMEDKHAN NAGORI NA MARKAZSAHI BAGARA NEAR MOHASAUDI ARABIA NA NA S00900006 220 2200 09‐MAY‐2018 PARVEEN SINGH RAWAT S S RAWAT SERVICE P‐16A VIJAY VIHAR UTTAM NAGAR INDIA Delhi 110059 S00004964 110 1100 09‐MAY‐2018 DAMJI SHAMJI HARIA SHAMJI HARIA SERVICE SALAS NAGAR D‐5 IIND FLOOR AAD INDIA Maharashtra 421301 S00005640 220 2200 09‐MAY‐2018 -

Selan Exploration Technology Ltd Unpaid

SELAN EXPLORATION TECHNOLOGY LTD UNPAID/UNCLAIM DIVIDEND SHARE HOLDER(IEPF-4) FOLIO NO NAME ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 ADD4 PIN SHARES 00000192 PANKAJ CHHOTALAL PARIKH 0 60 00000193 NINA MAHESH PAREKH 0 20 00000240 DHULDHOYA MANAN 61 B ARCHANA 204/205 NEW D N NAGAR ANDHERI W BOMBAY 400058 50 00000242 RACHANA V TANDON D WING GROUND FLOOR TRILOK CHSL MAYEKAR WADI VIRAT NAGAR VIHAR THANE MUMBAI 401303 20 00000256 P V UDAYA BHASKAR 3/Y E S I QUARTERS ADARSH NAGAR HYDERABAD 500463 220 00000275 JASJIT SINGH E 29 PANCH SHILA PARK NEW DELHI 110017 660 00000276 PREM BHAGAT A 25 ASHOK VIHAR PHASE II NEW DELHI 110052 10 00000325 K V KRISHNAN J- 47/1, DYAM VIHAR, DINDARPUR, NAJAFGARH, NEW DELHI 110043 20 00000455 RANJU MANTRI CHHAGAN MAL BHANWAR LAL POST PARIHARA DT CHURU RAJ 331505 220 00000460 CHANDRA KALA GUPTA 113/105 SWAROOP NAGAR KANPUR 208002 880 00000476 SUMITA SINGHAL DISTRICT HOSPITAL CAMPUS PO BAHARAICH UP 271801 330 00000513 AJAY ANAND 123 SAINIK VIHAR PRITAM PURA DELHI 110034 440 00000558 JAGRUTI SANGHAVI SHOP NO 6 EKATA TOWERS VASNA BARAGE ROAD VASNA AHMEDABAD 380007 110 00000562 SURESH BHAI SHAH SHOP NO 6 EKATA TOWERS VASNA BARRAGE ROAD VANSA AHMEDABAD 380007 110 00000699 RAMBHAI J PATEL OFF NO 2 SHETH M R S BUILDING OPP MARKET YARD STATION ROAD UNJHA N GUJ 384170 440 00000725 BHIKHIBEN PATEL 185 B FALGUN TENAMENTS JODHPUR GAM ROAD SATELITE AHMEDABAD 380015 550 00000733 AJIT BALDEVBHAI SHUKLA B/2/16 RAGHUKUL SOCIETY NR SHAHIBAG RLY CROSSING SHAHIBAG AHMEDABAD 380004 110 00000834 ANKIT C/O MINERVADYING COMPANY E-31 IND AREA POST BALOTRA RAJ 344022 -

A-PDF Image to PDF Demo. Purchase from To

A-PDF Image To PDF Demo. Purchase from www.A-PDF.com to remove the watermark Tainwala Chemicals And Plastics (India) Limited Annual Report 2010-2011 TAINWALA CHEMICALS AND PLASTICS INDIA LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010-2011 MANAGEMENT TEAM BANKERS DUNGARMAL TAINWALA Chairman and HDFC Bank Ltd. Whole-time Director REGISTERED OFFICE RAKESH TAINWALA Managing Director Tainwala House Road No. 18, M.I.D.C., ABHAY SHETH Independent Director Andheri (East), Mumbai-400 093 Tel: 67166100, SUBHASH KADAKIA Independent Director Fax : +91-22-28387039 Website: www.tainwala.in MAYANK DHULDHOYA Independent Director WORKS SIMRAN MANSUKHANI Vice President Accounts & CFO 87, Government Industrial Estate Khadoli Village, Silvassa - 396230 Dadra & Nagar Haveli - U.T. ASHOK MUKHERJEE Sr. Vice-President Marketing & REGISTRAR & SHARE TRANSFER Administration AGENTS V.M.RAJU General Manager Works LINK INTIME INDIA PVT. LTD C-13, Pannalal Silk Mills Compound, MILIND BURDE General Manager LBS Road, Bhandup (W), Mumbai 400 078. Commercial Tel.: 25963838. AUDITORS M/s RUNGTA & ASSOCIATES Chartered Accountants CONTENTS Mumbai Notice 2 Directors' Report 7 Corporate Governance 9 Management Discussion & Analysis 19 Auditor's Report 21 TWENTY SIXTH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Balance Sheet 24 Profit & Loss Account 25 • Tuesday, 27th September, 2011 Cash Flow 26 • 11.00 a.m. Schedules to Balance Sheet 27 • The All India Plastics Manufacturers Schedules to Profit & Loss Account 32 Association, A-52, Street No. 1, M.I.D.C. Significant Accounting Policies & Marol, Andheri (East), Mumbai - 400093. Notes to Accounts 35 1 Tainwala Chemicals And Plastics (India) Limited Annual Report 2010-2011 NOTICE Notice is hereby given that the TWENTY SIXTH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of the Members of TAINWALA CHEMICALS AND PLASTICS (INDIA) LIMITED will be held at The All India Plastics Manufacturers Association, A-52, Street No 1, M.I.D.C, Marol, Andheri (East), Mumbai - 400 093 on Tuesday, 27th September, 2011 at 11.00 a.m. -

Recruitment and Migration of South Indian Women As Domestic Workers to the Middle East

Background Paper In the Shadow of the State: Recruitment and Migration of South Indian Women as Domestic Workers to the Middle East Praveena Kodoth Copyright © International Labour Organization 2020 First published July 2020 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ISBN: 978-92-2-032402-8 (web PDF) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Form IEPF-2 2011-12

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L74899DL1985PLC021445 Prefill Company/Bank Name SELAN EXPLORATION TECHNOLOGY LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 12-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1271505.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) INDIRA S DAMANI SH SHANKAR LALHOUSEHOLD Baxi Street Morvi Gujarat INDIA Gujarat 363641 S00000052 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend330.00 01-MAR-2019 KAMLESH M SHAH SH MANGALDAS SERVICE 6 603 Vijay Chambers Thribhuvan RdINDIA Bombay 4 DELHI DELHI S00000142 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend660.00 01-MAR-2019 PANKAJ CHHOTALAL PARIKH SH CHHOTALAL PAREKHBUSINESS Abcd INDIA DELHI DELHI S00000192 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend660.00 01-MAR-2019 NINA MAHESH PAREKH SH MAHESH PAREKHBUSINESS -

Appendix Additional Castes, Caste Clusters

Appendix 309 out much of Tamil Nadu. (Thurston and Rangachari 1909, Appendix 1:5-16) Agasa (Asaga, Viraghata Madivala, Madiwal, Mallige Additional Castes, Madevi Vakkalu) Acaste ofwashermen, found in southern Maharashtra and Karnataka. They are Hindus, though many Caste Clusters, are Lingayats, and those speaking Konkani are Christians. See also Dhobi. (Thurston and Rangachari 1909, 1:16-18; and Tribes Enthoven 1920-1922, 1:1-5; Nanjundayya and Anantha- krishna Iyer 1928-1936, 2:1-31; Srinivas 1952) Aghori (Aughar, Aghoripanthi, Aghorapanthi) A class of The following caste and tribe names have been taken from Shaivite mendicants who used to feed on human corpses and the various sets of handbooks dealing with the castes and excrement; in previous centuries they were even reputed to tribes of particular regions of South Asia. These volumes are have engaged in cannibalism. Being a wandering people who nearly all more than a half-century old, but more recent infor- have commonly been chased out ofone district after another, mation of this sort is not available. (Virtually all of the they are now found widely scattered through India, although "Castes and Tribes" handbooks have, however, been repub- Varanasi (Benares) is thought to be their professional resort. lished in recent years.) Long as this list is, it is by no means (Risley 1891, 1:10; Crooke 1896, 1:26-69; Campbell 1901, exhaustive, and it merely represents those groups for which 543; Russell and Hira Lal 1916, 2:13-17) we have a certain amount of once reliable, if now outdated, information. Only monographs have been surveyed for this Agnihotri A Brahman caste devoted to the maintenance appendix, as space does not allow coverage of the massive ofthe sacred fire and found in northern India. -

Type Folio Holder Second Third Add1 Add2 Add3 Add4 Pin War 2009.00 War 2010 War 2011 War 2012 War 2013.00 War 2015.00 Shares Phy 0017414 Abdul Aziz Abdulla, 534, K.K

TYPE FOLIO HOLDER SECOND THIRD ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 ADD4 PIN WAR 2009.00 WAR 2010 WAR 2011 WAR 2012 WAR 2013.00 WAR 2015.00 SHARES PHY 0017414 ABDUL AZIZ ABDULLA, 534, K.K. NAGAR, MADURAI. 625001 1431667 1200.00 1632107 1600.00 1829387 1800.00 2027625 2000.00 2227720 2000.00 2324936 2500.00 40 PHY 0017437 P.T.P. ABDULLA, MBBS, PAPPINISSERI, CANNANORE DIST., KERALA. 670001 1431986 2940.00 1632328 3920.00 1829589 4410.00 2027812 4900.00 2228029 4900.00 2325241 6125.00 98 PHY 0017438 P.T.P. ABDULLA,M.B.B.S., PAPPINISSERI, CANNANORE DT., KERALA. 670001 1431987 2400.00 1632329 3200.00 1829590 3600.00 2027813 4000.00 2228030 4000.00 2325242 5000.00 80 PHY 0017483 KESHAV GANDAGHAV ABHYANKAR 64, MEDHA APARTMENT, TULSHIBAGWALE COLONY, SAHKARNAGAR NO.2, PUNE. 411009 1412719 1500.00 1614666 2000.00 1813518 2250.00 2012837 2500.00 2213454 2500.00 2311920 3125.00 50 PHY 0017504 SHANKARRAO LAXMANRAO ABHYANKAR, ABHYANKAR PHARMACY, WHOLE SALE GENERAL MARKET, GANDHI BAUG, NAGPUR-2. 440002 1429469 2400.00 1615257 3200.00 1814060 3600.00 2013340 4000.00 2214064 4000.00 2312478 5000.00 80 PHY 0017640 PHILIP ASSUMPTION ABRANCHES, C/O. MR. ALICK FERNANDEZ, 98, FATEH MANS LOVE LANE, MAZAGON, BOMBAY 10. 400010 1404820 1800.00 1607735 2400.00 1807397 2700.00 2007160 3000.00 2207713 3000.00 2306150 3750.00 60 PHY 0017651 SAJAN ABRAHAM NO 6/6TH CROSS GANESH BLOCK SULTANPALAYA BANGALORE 560032 1413909 1500.00 1616511 2000.00 1815217 2250.00 2014460 2500.00 2215308 2500.00 2313706 3125.00 50 PHY 0017699 ASHWIN MOTIRAM ACHARYA MRS JAYSHREE ASHWIN ACHARYA MR DINESH MOTIRAM ACHARYA MANI BHUWAN, 3RD FL, SADASHIV STREET, V P ROAD, BOMBAY , MAHARASHTRA.