Printed in the Netherlands 347 WATER RESOURCES in THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roll of Successful Examinees in the CRIMINOLOGIST LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on SEPTEMBER 21, 2009 & FF

Roll of Successful Examinees in the CRIMINOLOGIST LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on SEPTEMBER 21, 2009 & FF. DAYS Page: 2 of 102 Released on OCTOBER 6, 2009 Seq. No. N a m e 1 ABACA, DARWIN MANLAVI 2 ABACSA, DONA PANOPIO 3 ABAD, ANACLETO ACASIO 4 ABAD, DIRIELYN PADRIQUE 5 ABAD, FREDERICK EDROSO 6 ABAD, JASMIN PANER 7 ABAD, JOHN JAYSON VILLAS 8 ABAD, RAYMUND MANGULTONG 9 ABADESA, GARRY ARIAS 10 ABALOS, ROLLY JESON TAN 11 ABAN, EMMANUEL OPEMA 12 ABANA, DIVINA CABIT 13 ABANCO, ELMER JR FRANCISCO 14 ABANES, ANTONIO SALAZAR 15 ABANES, MARY JOY SERRADA 16 ABAO, JOHN MICHAEL FAJARDO 17 ABAO, JUNE NIL SALVADOR 18 ABARQUEZ, EDITH DE GUZMAN 19 ABAS, JOHN REY SACLAO 20 ABASTILLAS, ARLEN TOLENTINO 21 ABAT, MARK LESTER SANGALANG 22 ABAYA, HELBERT BUQUING 23 ABAÑO, JAY ESCOLANO 24 ABDULCARIL, NORIE JANE QUIROZ 25 ABDULLA, IDRIS DEXTER LOY MATURAN 26 ABDURAHIM, NASRI WAHAB 27 ABEL, HELEN LAGUA 28 ABEL, NATANIEL REGONDOLA 29 ABELARDE, JAQUELINE DELARMINO 30 ABELARDE, MANILYN REPEDRO 31 ABELITA, JENNIFER SOLIS 32 ABELLA, CRISTOPHER BICERA 33 ABELLA, ERIC TAN 34 ABELLA, EUGENIO CAIRO 35 ABELLA, FREDIERIC BERNAL 36 ABELLANA, FEL TIROL 37 ABELLANA, HERNANI JR ESTIPONA 38 ABELLANA, JESS NIÑO BORRA 39 ABELLANOSA, JEFFREY ABRAGAN 40 ABENA, JONNEL ARELLANO 41 ABENDANIO, VON DAREN ALUZAN 42 ABENDAÑO, RYAN BERGONIO 43 ABENES, ANDRE GREGORIO SABADO 44 ABES, ELIZABETH MAZO 45 ABIAD, FRANCIS JOYMER RODRIGUEZ 46 ABIDAL, ADRIAN ADUSAN 47 ABIQUE, ANGELITO ABRINA 48 ABIQUE, MORELIO JR CABALLERO 49 ABIVA, VICTOR SULQUIANO 50 ABLASA, ELFRED MAYAMNES Roll of Successful Examinees in the CRIMINOLOGIST LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on SEPTEMBER 21, 2009 & FF. -

Volunteer Camps in Kazakhstan in 2018

VOLUNTEER CAMPS IN KAZAKHSTAN IN 2018 During the summer and autumn of 2018, the Laboratory of Geoarchaeology (Faculty of History, Archeology and Ethnology, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University) is organizing archaeological investigations covering all periods from Palaeolithic to Modern times all over Kazakhstan. The programme of work consists mainly in mapping, documenting and collecting paleodata for analyses. Open-air lectures in the history, archaeology and paleoenvironment of Central Asia are included. Sessions will take place between June and October 2018 and are 15 days in duration. Volunteers and students of archaeology are welcome to join us. The participation fee is EU250 (or 300USD) per week and academic credit is given by the Kazakh National University. Interested volunteers and students of archaeology should contact the LGA to ask for full details on the various survey and excavation opportunities on offer. Renewed information is also available on the Laboratory of Geoarchaeology web site: http://www.lgakz.org/VolunteerCamps/Volunteer.html Or you can check the updated announcement of our volunteer camps on the Fieldwork webpage of the Archaeological Institute of America There will be 4 expeditions occurring from June 1, 2018 - October 31, 2018 1) Chu-Ili mountains (Petroglyphs documentation): 15 June-5 July; 7-22 August 2) Botai region (Geoarchaeological study): 14-31 July 3) Syrdarya delta (Geoarchaeological study): 8-30 September 4) North Balkhash lake region (Geoarchaeological study): 8-22 October Application Deadline: -

DRAINAGE BASINS of the WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA and KARA SEA Chapter 1

38 DRAINAGE BASINS OF THE WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA Chapter 1 WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA 39 41 OULANKA RIVER BASIN 42 TULOMA RIVER BASIN 44 JAKOBSELV RIVER BASIN 44 PAATSJOKI RIVER BASIN 45 LAKE INARI 47 NÄATAMÖ RIVER BASIN 47 TENO RIVER BASIN 49 YENISEY RIVER BASIN 51 OB RIVER BASIN Chapter 1 40 WHITE SEA, BARENT SEA AND KARA SEA This chapter deals with major transboundary rivers discharging into the White Sea, the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea and their major transboundary tributaries. It also includes lakes located within the basins of these seas. TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN THE BASINS OF THE BARENTS SEA, THE WHITE SEA AND THE KARA SEA Basin/sub-basin(s) Total area (km2) Recipient Riparian countries Lakes in the basin Oulanka …1 White Sea FI, RU … Kola Fjord > Tuloma 21,140 FI, RU … Barents Sea Jacobselv 400 Barents Sea NO, RU … Paatsjoki 18,403 Barents Sea FI, NO, RU Lake Inari Näätämö 2,962 Barents Sea FI, NO, RU … Teno 16,386 Barents Sea FI, NO … Yenisey 2,580,000 Kara Sea MN, RU … Lake Baikal > - Selenga 447,000 Angara > Yenisey > MN, RU Kara Sea Ob 2,972,493 Kara Sea CN, KZ, MN, RU - Irtysh 1,643,000 Ob CN, KZ, MN, RU - Tobol 426,000 Irtysh KZ, RU - Ishim 176,000 Irtysh KZ, RU 1 5,566 km2 to Lake Paanajärvi and 18,800 km2 to the White Sea. Chapter 1 WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA 41 OULANKA RIVER BASIN1 Finland (upstream country) and the Russian Federation (downstream country) share the basin of the Oulanka River. -

Bronze Age Human Communities in the Southern Urals Steppe: Sintashta-Petrovka Social and Subsistence Organization

BRONZE AGE HUMAN COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTHERN URALS STEPPE: SINTASHTA-PETROVKA SOCIAL AND SUBSISTENCE ORGANIZATION by Igor V. Chechushkov B.A. (History), South Ural State University, 2005 Candidate of Sciences (History), Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2013 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2018 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Igor V. Chechushkov It was defended on April 4, 2018 and approved by Dr. Francis Allard, Professor, Department of Anthropology, Indiana University of Pennsylvania Dr. Loukas Barton, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Marc Bermann, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Robert D. Drennan, Distinguished Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Igor V. Chechushkov 2018 iii BRONZE AGE HUMAN COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTHERN URALS STEPPE: SINTASHTA-PETROVKA SOCIAL AND SUBSISTENCE ORGANIZATION Igor V. Chechushkov, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Why and how exactly social complexity develops through time from small-scale groups to the level of large and complex institutions is an essential social science question. Through studying the Late Bronze Age Sintashta-Petrovka chiefdoms of the southern Urals (cal. 2050–1750 BC), this research aims to contribute to an understanding of variation in the organization of local com- munities in chiefdoms. It set out to document a segment of the Sintashta-Petrovka population not previously recognized in the archaeological record and learn about how this segment of the population related to the rest of the society. -

Of Key Sites for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central ASIA of Keysitesforthesiberian Crane Ndotherwterbirds in Western/Centralasi Atlas

A SI L A L A ATLAS OF KEY SITES FOR THE SIBERIAN CRANE AND OTHER WATERBIRDS IN WESTERN/CENTRAL ASIA TERBIRDS IN WESTERN/CENTR TERBIRDS IN A ND OTHER W ND OTHER A NE A N CR A IBERI S S OF KEY SITES FOR THE SITES FOR KEY S OF A ATL Citation: Ilyashenko, E.I., ed., 2010. Atlas of Key Sites for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central Asia. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA. 116 p. Editor and compiler: Elena Ilyashenko Editorial Board: Crawford Prentice & Sara Gavney Moore Cartographers: Alexander Aleinikov, Mikhail Stishov English editor: Julie Oesper Layout: Elena Ilyashenko Atlas for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central Asia ATLAS OF THE SIBERIAN CRANE SITES IN WESTERN/CENTRAL ASIA Elena I. Ilyashenko (editor) International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA 2010 1 Atlas for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central Asia Contents Foreword from the International Crane Foundation George Archibald ..................................... 3 Foreword from the Convention on Migratory Species Douglas Hykle........................................ 4 Introduction Elena Ilyashenko........................................................................................ 5 Western/Central Asian Flyway Breeding Grounds Russia....................................................................................................................... 9 Central Asian Flock 1. Kunovat Alexander Sorokin & Anastasia Shilina ............................................................. -

Jilili Abuduwaili · Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov Hydrology and Limnology of Central Asia Water Resources Development and Management

Water Resources Development and Management Jilili Abuduwaili · Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov Hydrology and Limnology of Central Asia Water Resources Development and Management Series editors Asit K. Biswas, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore Cecilia Tortajada, Institute of Water Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore Editorial Board Dogan Altinbilek, Ankara, Turkey Francisco González-Gómez, Granada, Spain Chennat Gopalakrishnan, Honolulu, USA James Horne, Canberra, Australia David J. Molden, Kathmandu, Nepal Olli Varis, Helsinki, Finland Hao Wang, Beijing, China [email protected] More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7009 [email protected] Jilili Abuduwaili • Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov Hydrology and Limnology of Central Asia 123 [email protected] Jilili Abuduwaili and State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology Faculty of Geography and Environmental and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences Sciences Al-Farabi Kazakh National University Urumqi Almaty China Kazakhstan and and Research Centre of Ecology and Research Centre of Ecology and Environment of Central Asia (Almaty) Environment of Central Asia (Almaty) Almaty Almaty Kazakhstan Kazakhstan Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Research Centre of Ecology and Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology Environment of Central Asia (Almaty) and Geography, Chinese Academy of U.U. Uspanov Kazakh Research Institute of Sciences Soil Science and Agrochemistry Urumqi Almaty China Kazakhstan ISSN 1614-810X ISSN 2198-316X (electronic) Water Resources Development and Management ISBN 978-981-13-0928-1 ISBN 978-981-13-0929-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0929-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018943710 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

Creation of Perishable Goods Licensing and Certification

Development of Equipment Certification Centres for the Transportation of Perishable Goods in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in the frame of ATP Agreement. EuropeAid/123761/C/Ser/Multi An EU Funded Project The European Union’s TRACECA Programme for “Partner Country” Development of Equipment Certification Centres for the Transportation of Perishable Goods in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in the frame of ATP Agreement EuropeAid/123761/C/SER/Multi nd 2 Project Progress Report – January to June 2008 This project is funded by A project implemented by the Consortium the European Union SAFEGE, RINA Industry and IRD Engineering Form 1.2. REPORT COVER PAGE An EU Funded Project under the Consortium Management of the following companies: 1 Development of Equipment Certification Centres for the Transportation of Perishable Goods in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in the frame of ATP Agreement. EuropeAid/123761/C/Ser/Multi An EU Funded Project Project Title: DEVELOPMENT OF EQUIPMENT CERTIFICATION CENTRES FOR THE TRANSPORTATION OF PERISHABLE GOODS IN KAZAKHSTAN, KYRGYZ REPUBLIC, TAJIKISTAN, REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN AND REPUBLIC OF TURKMENISTAN IN THE FRAME OF ATP AGREEMENT. : Project Number : EUROPEAID/123761/C/SER/Multi Service Contract n. 123 Country : Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan Project Partner EC Contractor Name : Designated Partner Consortium Safege, Rina, IRD Address : Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan 15-27 rue du Port – Parc -

Biomass Resources of Phragmites Australis in Kazakhstan: Historical Developments, Utilization, and Prospects

resources Review Biomass Resources of Phragmites australis in Kazakhstan: Historical Developments, Utilization, and Prospects Azim Baibagyssov 1,2,3,*, Niels Thevs 2,4, Sabir Nurtazin 1, Rainer Waldhardt 3, Volker Beckmann 2 and Ruslan Salmurzauly 1 1 Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty 050010, Kazakhstan; [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (R.S.) 2 Faculty of Law and Economics & Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald, 17489 Greifswald, Germany; [email protected] (N.T.); [email protected] (V.B.) 3 Division of Landscape Ecology and Landscape Planning, Institute of Landscape Ecology and Resources Management, Center for International Development and Environmental Research (ZEU), Justus Liebig University Giessen, 35390 Giessen, Germany; [email protected] 4 Central Asia Office, World Agroforestry Center, Bishkek 720001, Kyrgyzstan * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 5 April 2020; Accepted: 12 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: Common reed (Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steud.) is a highly productive wetland plant and a potentially valuable source of renewable biomass worldwide. There is more than 10 million ha of reed area globally, distributed mainly across Eurasia followed by America and Africa. The literature analysis in this paper revealed that Kazakhstan alone harbored ca. 1,600,000–3,000,000 ha of reed area, mostly distributed in the deltas and along the rivers of the country. Herein, we explored 1 the total reed biomass stock of 17 million t year− which is potentially available for harvesting in the context of wise use of wetlands. -

Detrital Thermochronology to Constrain Meso-Cenozoic Intramontane Basin Evolution in the Northern Tien Shan (Central Asia)

FACULTY OF SCIENCES Master of Science in geology Coupling basement and detrital thermochronology to constrain Meso-Cenozoic intramontane basin evolution in the northern Tien Shan (Central Asia) Simon Nachtergaele Academic year 2015–2016 Master’s dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Science in Geology Promotor: Prof. Dr. Johan De Grave Tutor: Elien De Pelsmaeker Jury: Prof. Dr. Marc De Batist, Dr. Damien Delvaux “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.“ (Albert Einstein) Acknowledgements First of all I want to thank my thesis promoter Prof. Dr. Johan De Grave for the creation of this thesis subject and giving me the possibility to join the team on the Kyrgyz field. He also corrected my strange grammar constructions and last but not least for the time that he invested in me, while he was very busy with teaching and research. Research on geochronology is time-consuming and the interpretation of geochronological data is often complex. I experienced geochronology in Central-Asia as a challenging and therefore attractive research subject. The next person that I want to thank is research assistant Elien De Pelsmaeker. Despite the heavy teaching load, she always was available for answering my questions. She also calmed me down when a lot of samples appeared to be worthless in november/december 2015. Also during the ‘zircon U/Pb disappointment’, we stayed calm and decided to focuse more on apatite fission track analysis. Our team work in the Tien Shan mountains during the summer of 2015 was an unforgettable experience. -

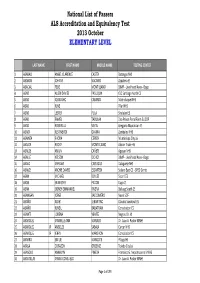

2013 El Oct for Web.Xlsx

National List of Passers ALS Accreditation and Equivalency Test 2013 October ELEMENTARY LEVEL LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME TESTING CENTER 1 ABABAO ANGEL CLARENCE CASTEN Batangas NHS 2 ABABON JOHNNY NACARIO Zapatera ES 3 ABACIAL PEJIE MONTILLANO BJMP - Livelihood Area - Bogo 4 ABAD ALLEN DAVIES PASUQUIN CLC Santiago North CS 5 ABAD JOANA JHO CABARDA Marinduque NHS 6 ABAD JUNE Pilar NHS 7 ABAD LESTER PULA Sindalan ES 8 ABAD RAMEL TADULAN Dvo Prison Penal Farm BUCOR 9 ABAD ROSEVILLA VISTAL Gregorio Maoralizon ES 10 ABADA JUSTINE ROI GAVINA Zambales NHS 11 ABAINZA RHODA CEPEDA Muntinlupa City Jail 12 ABAJON ROCKY MONTECALBO Aloran Trade HS 13 ABALDE ANJUN CAÑETE Agusan NHS 14 ABALLE NELSON DICHOS BJMP - Livelihood Area - Bogo 15 ABALO MERIAM CARIAGGA Dalaguete NHS 16 ABALOS ARCHIE DAVED ESCARTEN Solano East CS - SPED Center 17 ABAN MICHAEL BOYLES Sison CES 18 ABAN SELBESTER PADON Cuyo CS 19 ABAN SIDNEY EMMANUEL RIVERA Baliuag South CS 20 ABANGAN JORGE BALDOMERO Naval SOF 21 ABAÑO JULIET LEBANTINO Claudio Sandoval ES 22 ABAÑO JUNEIL BABATUAN Consolacion CS 23 ABANTE LORENA YBAÑEZ Negros Or. HS 24 ABARQUEZ MARIELLE ANN MANALO Dr. Juan A. Pastor MNHS 25 ABARQUEZ JR ANGELES SABALA Carcar NHS 26 ABARQUEZ JR JERRY MAROHOM Consolacion CS 27 ABARRO EMILIE MARGOTE Pitogo HS 28 ABASA CORAZON ORDENIZ Toledo City Jail 29 ABASOLO ANNALYN PINEDA Francisco G. Nepomuceno MNHS 30 ABASTILLAS MARIA CONSUELO Dr. Juan A. Pastor MNHS Page 1 of 199 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME TESTING CENTER 1 ABABAO ANGEL CLARENCE CASTEN Batangas NHS 2 ABABON JOHNNY NACARIO Zapatera ES 3 ABACIAL PEJIE MONTILLANO BJMP - Livelihood Area - Bogo 4 ABAD ALLEN DAVIES PASUQUIN CLC Santiago North CS 5 ABAD JOANA JHO CABARDA Marinduque NHS 6 ABAD JUNE Pilar NHS 7 ABAD LESTER PULA Sindalan ES 31 ABAY RICKY RAS Baliuag South CS 32 ABAY-ABAY ROCELIA BASENSE Sta. -

Supplement of Geosci

Supplement of Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 1343–1375, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-1343-2018-supplement © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of LPJmL4 – a dynamic global vegetation model with managed land – Part 1: Model description Sibyll Schaphoff et al. Correspondence to: Sibyll Schaphoff ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. S1 Supplementary informations to the evaluation of the LPJmL4 model The here provided supplementary informations give more details to the evaluations given in Schaphoff et al.(under Revision). All sources and data used are described in detail there. Here we present ad- ditional figures for evaluating the LPJmL4 model on a plot scale for water and carbon fluxes Fig. S1 5 - S16. Here we use the standard input as described by Schaphoff et al.(under Revision, Section 2.1). Furthermore, we evaluate the model performance on eddy flux tower sites by using site specific me- teorological input data provided by http://fluxnet.fluxdata.org/data/la-thuile-dataset/(ORNL DAAC, 2011). Here the long time spin up of 5000 years was made with the input data described in Schaphoff et al.(under Revision), but an additional spin up of 30 years was conducted with the site specific 10 input data followed by the transient run given by the observation period. Comparisons are shown for some illustrative stations for net ecosystem exchange (NEE) in Fig. S17 and for evapotranspira- tion Fig. S18. -

Environmental and Social Compliance Audit Report KAZ: RG Brands Agribusiness Project

Environmental and Social Compliance Audit Report Project Number: 46944 March 2013 KAZ: RG Brands Agribusiness Project Prepared by DG Consulting Ltd for RG Brands This environmental and social compliance audit report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “Term of Use” section of this website. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL DUE DILIGENCE REPORT RG BRANDS AGRIBUSINESS PROJECT Final Version 41140_R1_Eng January 2013 DG Consulting Ltd Address: 1. Mitrophane Lagidze Street, 0108, Tbilisi, Georgia; Registered office: 5 Shevardenidze Street, 0177, Tbilisi, Georgia; Reg No 205 280 998; Tel: +995 322 997 497; +995 599 500 778; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 41140_R1_Eng Page 2 of 110 Signatures chapter Prepared by: The present Report is prepared by DG Consulting Ltd Project Manager – David Girgvliani Revision Table chapter Revision # Revised Part of Document Reason of Revision DG Consulting Ltd 41140_R1_Eng Page 3 of 110 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 8 1 Nature of the Project ........................................................................................................................... 18 1.1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................