Psalm 78:1-72 Forgetting the Unforgettable Asaph's Sermon Uses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Psalm 105 Continued

Psalm 105 Continued In the last lesson we were studying about Joseph being sold into Egypt by his brothers, winding up in jail, and becoming second to the Pharaoh as part of God's plan to get the family of Jacob into Egypt. Psalm 105:20 "The king sent and loosed him; [even] the ruler of the people, and let him go free." Released him from prison (Gen. 41:14). The object was that he might interpret the dreams of Pharaoh. "The ruler of the people, and let him go free": Hebrew, "peoples," in the plural, referring either to the fact that there were "many" people in the land, or that Pharaoh ruled over tributary nations as well as over the Egyptians. This is saying that Pharaoh himself, let Joseph out of jail. Psalm 105:21 "He made him lord of his house, and ruler of all his substance:" (Gen. 41:40). This implied that the administration of the affairs of the nation was virtually committed to him. "And ruler of all his substance": Margin, as in Hebrew, "possession." Of all he had. He placed all at his disposal in the affairs of his kingdom. When Joseph interpreted the dream of the Pharaoh with a plan to save their land, Pharaoh made Joseph second only to himself. Psalm 105:22 "To bind his princes at his pleasure; and teach his senators wisdom." Giving him absolute power. The power here referred to was that which was always claimed in despotic governments, and was, and is still, actually practiced in Oriental nations. -

Bible Reading

How can a young person stay A V O N D A L E B I B L E C H U R C H D, on the path of purity? By OCUSE RIST F RED living according to your CH CENTE BIBLE word. I seek you with all my r heart; do not let me stray gethe from your commands. I have To hidden your word in my heart that I might not sin Your word is a lamp against you. Praise be to you, unto my feet and a Lord teach me your light to my path decrees. With my lips I recount all the laws that -PSALM 119:105 come from your mouth. I E H T SEPTEMBER rejoice in following your N I WED 1 Psalm 136 statutes as one rejoices in THU 2 Psalms 137-138 R great riches. I meditate on E FRI 3 Psalm 129 M SAT 4 Psalm 140-141 your precepts and consider M U SUN 5 Psalm 142, 139 your ways. I delight in your S MON 6 Psalm 143 decrees; I will not neglect TUE 7 Psalm 144 your word. WED 8 Psalm 145 PSALM 119:9-16 THU 9 Psalm 146 FRI 10 Psalms 147-148 SAT 11 Psalms 149-150 SUMMER 2021 SUN 12 Joshua 1 Every word of God is flawless; JULY AUGU ST THU 1 Psalms 27-28 SUN 1 Psalms 81-82, 63 he is a shield to those who FRI 2 Psalms 29-30 MON 2 Psalms 83-84 take refuge in him. -

The Psalmists' Use of the Exodus Motif

The Psalmists’ Use of the Exodus Motif A Close Reading and Intertextual Analysis of Selected Exodus Psalms Thesis Submitted for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by David Emanuel Submitted to the Senate of the Hebrew University December 2007 This work was written under the supervision of Professor Yair Zakovitch CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................................................. VIII INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 RESEARCH IN RELATED FIELDS ................................................................................................................................. 3 General Psalms Research ................................................................................................................................... 3 Inner-Biblical Interpretation and Allusion ......................................................................................................... 6 Juxtapositional Interpretation ............................................................................................................................ 8 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS .................................................................................................................... 10 SCOPE AND STRUCTURE ........................................................................................................................................ -

Psalms Yalmoi ?????????? ????? Psalms Is the Book of Praises

One Year Through the Bible by Pastor Bob Bolender Week 16 – 2 Samuel 7,8; various Psalms Page 1 of 8 One Year Through the Bible, by Pastor Bob Bolender Week 16 – 2 Samuel 7, 8; various Psalms Week 16 Bible Readings Sunday: Psa. 78,96 Monday: Psa. 15,24,68 Tuesday: Psa. 132,133 Wednesday: Psa. 106,105 Thursday: 2nd Sam. 7; Psa. 16,2 Friday: Psa. 110; 2nd Sam. 8; Psa. 97,98 Saturday: Psa. 108,117,118 Week 16 Chapter Titles 2 Samuel 7 The Davidic Covenant Stated 2 Samuel 8 David the Mighty Conqueror Psalm 2 The King Rejected but Coming to Reign Psalm 15 The Regenerate Described Psalm 16 Death & Resurrection Psalm 24 The Chief Shepherd (Coming) Psalm 68 Victorious Procession of God Psalm 78 The History of God’s Grace with Israel Psalm 96 Praise and Testimony in View of the 2nd Advent Psalm 97 “The Lord Reigneth” Psalm Psalm 98 A New Song of Victory Psalm 105 Israel’s History & God’s Mercy Psalm 106 Israel’s Failure & God’s Grace Psalm 108 Praise for Victory Psalm 110 Christ as King and Priest Psalm 117 The Shortest Psalm (praise) Psalm 118 The Exalted Christ Psalm 132 Davidic Covenant Psalm Psalm 133 A Psalm of Fellowship Psalms Yalmoi ?????????? ????? Psalms is the Book of Praises. The worship hymnal for the Scriptures contains 150 songs of praise and worship for the glory of the Lord. This worship is grounded in the character of God, and the greatness of His work. The doctrinal content of Psalms demonstrates the reality of the Old Testament Christian Way of Life on a very practical level. -

150 Psalms Celebration of Life Tue 3 Mar 2020, 8Pm, Adelaide Town Hall

12 150 Psalms Celebration of Life Tue 3 Mar 2020, 8pm, Adelaide Town Hall Netherlands Chamber Choir with The Norwegian Soloists’ Choir, The Tallis Scholars & The Song Company Peter Dijkstra, conductor Anthony Hunt, organ Introduction by Kerry O’Brien Andreas Hammerschmidt (ca.1611-1675) Psalm 24, Machet die Tore weit Caroline Shaw (b. 1982) Psalm 84, and the swallow (Australian premiere) Chiara Maria Cozzolani (1602-1678) Psalm 110, Dixit Dominus Alessandro Costantini (ca.1581-1657) Psalm 136, Confitemini Domino Adriano Banchieri (1568-1634) Psalm 47, Omnes gentes plaudite Urmas Sisask (b. 1960) Psalm 105, Confitemini Domino Zoltan Kodály (1882-1967) Psalm 50, Az erős Isten Vic Nees (1936-2013) Psalm 87, Fundamenta ejus Henry Purcell (1659-1695) Psalm 106, O give thanks Jakob Gallus (1550-1591) Psalm 150, Laudate Dominum Ruggiero Giovannelli (ca.1560-1625) Psalm 149, Cantate Domino Jan Tollius (ca.1550-1620?) Psalm 68, Sicut fluit cera Isidora Žebeljan (1967) Psalm 78 (Australian premiere) Aleksandr Gretchaninov (1864-1956) Psalm 135, Praise the Name of the Lord Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Psalm 81, Exultate Deo Thomas Tallis (1505 - 1585) Spem in Alium Presenting Partner Netherlands Chamber Choir is supported by the Performing Arts Fund NL The Norwegian Soloists’ Choir is supported by Music Norway and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Supported by Amnesty International Commissioned works supported by the Commissioning Circle death rate in the hundreds of thousands. 26 billionaires have the same wealth as the Kerry O’Brien, speaker poorest 3.8 billion. The slow drip erosion of press freedom and fundamental human rights under the One Australian study has found that Kerry O’Brien is one of Australia’s most respected brittle and secretive banner of national income inequalities are greater now than journalists, with six Walkley awards including the Gold security, with the prosecution of Julian at any other time in the past 70 years. -

PSALM Background Notes

P a g e | 1 PSALM Background Notes As we read the Psalms together and ‘SING’ them as they should be sung a few background notes on how the Psalter is split up might be helpful 1. The Origin of the word ‘Psalm’ • The Greek word is ‘PSALMOS’ • From the Hebrew word meaning ‘to pluck’ as in what you do with a stringed instrument • Implies that the Psalms were composed to be accompanied by stringed instruments • Psalms are songs for the lyre and therefore lyric poems in the strictest sense • David and others originally wrote the Psalms to be sung with the harp 2. In NT worship we are told to sing the Psalms in our hearts. • ‘ ... singing and making melody to the Lord’ Eph 5:19 • The phrase ‘making melody’ comes from the Greek word ‘psallontes’ (literally, ‘plucking the strings of’) • Thus, we are to ‘pluck the strings of our heart’ as we sing Psalms 3. The History of the Psalms • The oldest of the Psalms originate from Moses • Exodus 15:1 to 15 – a song of triumph following the crossing of the Red Sea • Deuteronomy 32 and 33 – a song of exhortation to keep the Law after entering Canaan • Psalm 90 – a song of meditation, reflection and prayer • After Moses the writing of the Psalms had its good and bad moments • In David’s time (around BC 1000) it reached its full maturity • Under Solomon the creation of Psalms began to decline • Only twice after this did the creation of Psalms rise to any height Under Jehoshaphat in ca. -

DAILY BREAD the WORD of GOD in a YEAR by the Late Rev

DAILY BREAD THE WORD OF GOD IN A YEAR By the late Rev. R. M. M’Cheyne, M.A. THE ADVANTAGES • The whole Bible will be read through in an orderly manner in the course of a year. • Read the Old Testament once, the New Testament and Acts twice. Many of you may never have read the whole Bible, and yet it is all equally divine.“All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, and instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be perfect.” If we pass over some parts of Scripture, we will be incomplete Christians. • Time will not be wasted in choosing what portions to read. • Often believers are at a loss to determine towards which part of the mountains of spices they should bend their steps. Here the question will be solved at once in a very simple manner. • The pastor will know in which part of the pasture the flock are feeding. • He will thus be enabled to speak more suitably to them on the sabbath; and both pastor and elders will be able to drop a word of light and comfort in visiting from house to house, which will be more readily responded to. • The sweet bond of Christian unity will be strengthened. • We shall often be lead to think of those dear brothers and sisters in the Lord, who agree to join with us in reading these portions. We shall more often be led to agree on earth, touching something we shall ask of God. -

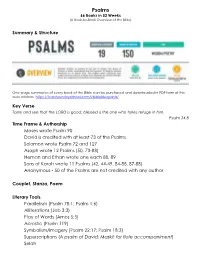

Psalms 66 Books in 52 Weeks (A Book-By-Book Overview of the Bible)

Psalms 66 Books in 52 Weeks (A Book-by-Book Overview of the Bible) Summary & Structure One-page summaries of every book of the Bible can be purchased and downloaded in PDF form at this web address. https://teachsundayschool.com/i/bibleblueprints/ Key Verse Taste and see that the LORD is good; blessed is the one who takes refuge in him. Psalm 34:8 Time Frame & Authorship Moses wrote Psalm 90 David is credited with at least 73 of the Psalms Solomon wrote Psalm 72 and 127 Asaph wrote 12 Psalms (50, 73-83) Heman and Ethan wrote one each 88, 89 Sons of Korah wrote 11 Psalms (42, 44-49, 84-85, 87-88) Anonymous - 50 of the Psalms are not credited with any author Couplet, Stanza, Poem Literary Tools Parallelism (Psalm 78:1; Psalm 1:6) Alliterations (Job 3:3) Play of Words (Amos 5:5) Acrostic (Psalm 119) Symbolism/Imagery (Psalm 22:17; Psalm 18:3) Superscriptions (A psalm of David; Maskil; for flute accompaniment) Selah Types of Psalms Hymns (Psalm 8) Lament (Psalm 55) Thanksgiving (Psalm 100) Imprecatory (Psalm 69:23-28) Royal (Psalm 20, 21, 72) Pilgrim/Psalms of Ascent (Psalms 120-134) Wisdom (Psalm 1) Enthronement (Psalm 47, 93, 99) Messianic (Psalm 2, 22,110) Structure The book of Psalms is divided into five collections, each ending with a song of praise. Five Doxologies in Psalms Psalm 41:13; Psalm 72:18-19; Psalm 89:52; Psalm 106:48; Psalm 150 Pentateuch Approach to Psalms ‘Virtual Temple’ Approach to Psalms (bibleproject.com) Sections 1 & 2 –David & His Royal Family Section 3—Tragedy Israel’s Exile Sections 4 & 5 –Hope for Messiah/Temple/Kingdom -

Reading Psalm 78 Multidimensionally: the Authorial Dimension1

Scriptura 84 (2003), pp. 468-484 READING PSALM 78 MULTIDIMENSIONALLY: THE AUTHORIAL DIMENSION1 Yeol Kim & HF van Rooy School for Biblical Studies Northwest University Abstract This article is part of an attempt to read Psalm 78 multidimensionally. It is the second in a proposed series of three articles.2 The articles deal with the dimension of the author, as part of the multi-dimensional reading. It deals with the heading of the Psalm, íhe redaction history of the Psalm, its dating and historical setting and its canonical shape. The Sitz im Leben of the psalm is the recitation of the psalm in the Jerusalem temple by a (Levitical) priest, when there was an attempt to unite the worship of the North and the South during the divided monarchy (922-587 B.C.). The traditions of wisdom, covenant-Torah, guidance, wilderness, Exodus, and conquest are united in Psalm 78, forming a new welded tradition which stresses the importance of remembrance with regard to the survival of the ancient traditions. Psalm 78 can be seen as an example of God’s response to íhe questions and complaints from the adjacent psalms and other psalms in Book III of the Psalter. In this regard, Psalm 78 is not a mere report of Israel’s failure, but of the triumph of Yahweh’s covenantal faithfulness which creates a new beginning for the people of God. 1. Introduction This article is the second in a series of articles on Psalm 78. The different articles are part of an experiment in a multidimensional reading and each of them will deal independently with an aspect of the interpretation of Psalm 78. -

“The Good Shepherd” Psalm 78:70–72; Jeremiah 23:1–4; John 10 Rev

“The Good Shepherd” Psalm 78:70–72; Jeremiah 23:1–4; John 10 Rev. Phil Reddick May 28, 2017 • Evening Sermon In this study I have two purposes. One I want to encourage you and two I want to point you to Jesus. We are here in remembrance of Him and then I’ll let the Holy Spirit do the rest of the work. Let’s pray. Prayer: Father, I thank You that we can gather in Your Name. We acknowledge Your Lordship. We thank You for Your sustaining grace. We are grateful to remember Your sacrifice for us even as we remember others who have given their life and the demonstration of how You lay down Your life for us. We pray this in Jesus’ Name, Amen. Psalm 23 says [1] The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want. [2] He makes me lie down in green pastures. He leads me beside still waters. [3] He restores my soul. He leads me in paths of righteousness for his name's sake. [4] Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me. [5] You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies; you anoint my head with oil; my cup overflows. [6] Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of the LORD forever . These words are very familiar to you. At probably almost every funeral you have been to, you have heard those words or you have seen them printed on the flier you get when you go to that funeral. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal