Text-Aided Archeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

Inter-University Master's Degree in Classical Archaeology

Study Plan AY 2020/21 Inter-University Master’s Degree in Classical Archaeology In English Language Class LM-2 Master’s Degree in Archaeology DEGREE REGULATIONS UnitelmaSapienza.it Study Plan AY 2020/21 Foreword The inter-university Master’s Degree in Classical Archaeology issues a joint degree between Sapienza University of Rome, one of the oldest universities in Italy and worldwide, with a secular leading role in Classics and archaeological studies, and UnitelmaSapienza University of Rome, its online university, which has been a flagship of excellence in Italian distance learning for over ten years. The Master is an online program that aims to provide an in-depth training in the field of classical archaeology, completing theoretical training with one or more apprenticeships in Rome or other archaeological sites to be agreed upon with the course board directors. The didactic methodology combines both traditional (historical-archaeological, philological-linguistic, artistic knowledge) and innovative resources applying the most evolved methods addressed to the knowledge of the material culture. The program aims to improve the archaeological and historical skills of second level graduates. Graduates can aspire to be future researchers with solid theoretical and practical training in archaeological disciplines within European and Middle-Eastern territories. The acquired knowledge and competencies will allow the graduates to be employed as professional archaeologists or cultural experts in a wide range of potential institutions, such as those connected to cultural heritage management, protection and valorisation, e.g. museums, archaeological sites, local authorities managing cultural projects; public administrations; universities and other academic and research entities; archaeological excavations associations or cooperatives; organisations working in the field of tourism, history, architecture, art, etc.; entities engaged in the promotion of archaeological heritages at national or inter-national level. -

INTRODUCTION to CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Spring 2018 Location; Time (Twice a Week/75 Mins)

INTRODUCTION TO CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Spring 2018 Location; Time (twice a week/75 mins) Instructor: Dr. Bice Peruzzi, Office: xxx. Office phone: xxx Email: xxx (expect a response within 24 hours) Office hours: xxx; (or by appointment) COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course is an introductory survey of the archaeology, architecture and material culture of the Mediterranean world from the Bronze Age throughout the transformation of the Roman Empire following the reign of Constantine. While we consider chronological developments, we will also place Greek and Roman artistic production into its social and cultural settings. Along the way we will think about approaches and methodologies for the study of Classical Art, and how these may tell us more about ourselves than the ancient Greeks and Romans. CORE LEARNING GOALS: This course is certified for the following learning goals: HST/SCLh: Understand the bases and development of human and societal endeavors across time and place. HSTk: Explain the development of some aspect of a society or culture over time, including the history of ideas or history of science. AHp: Analyze arts and/or literatures in themselves and in relation to specific histories, values, languages, cultures, and technologies. COURSE LEARNING GOALS: At the end of this course, the successful student will be able: To describe the main artistic contributions of the Ancient Greeks and Roman, and to explain their significance; To identify the broad historical periods of Ancient Greece and Rome and to place major events and artistic personalities within those periods; To learn about the daily lives of the ancient Greeks and Romans, including women, children, and slaves; To distinguish primary source evidence and secondary source and to acknowledge strengths and weaknesses in each. -

Classical Archaeology As a Major in a Bachelor’S Degree Programme with the Degree "Bachelor of Arts" (120 ECTS Credits)

Subdivided Module Catalogue for the Subject Classical Archaeology as a major in a Bachelor’s degree programme with the degree "Bachelor of Arts" (120 ECTS credits) Examination regulations version: 2018 Responsible: Faculty of Arts, Historical, Philological, Cultural and Geographical Studies Responsible: Institute of Ancient Cultures JMU Würzburg • generated 23-Aug-2021 • exam. reg. data record B1|012|-|-|H|2018 Subdivided Module Catalogue for the Subject Classical Archaeology major in a Bachelor’s degree programme, 120 ECTS credits Course of Studies - Contents and Objectives A major for a Bachelor’s degree, the degree subject Classical Archaeology is offered by the Faculty of Arts of JMU in the framework of a programme combining a major and a minor. That programme focuses on the fundamental principles of the disciplines and leads to the degree of Bachelor of Arts (BA). The Bachelor of Arts degree is a first professional university degree. Students are equipped with an overview of the individual branches of classical archaeology and with the methods commonly used in the discipline and thus acquire a good foundation for further studies at Master’s level. Studying Classical Archaeology, students • learn the fundamental principles of the main branches of classical archaeology as well as the methods commonly used in the discipline. • develop an ability for abstraction and learn how to structure complex problems as well as to develop alternative solutions by combining fragmentary and selective pieces of information. • develop the ability to use interdisciplinary approaches to solve problems (by studying a combination of two subjects). major in a Bachelor’s degree programme Classical JMU Würzburg • generated 23-Aug-2021 • exam. -

Justin Leidwanger

CV: Leidwanger, November 2020 Page 1 of 21 JUSTIN LEIDWANGER [email protected] (O) 650.723.9068 | (M) 215.749.2558 Office Lab Department of Classics, Room 210 Archaeology Center, Rooms 211-212 450 Jane Stanford Way 488 Escondido Mall Main Quad, Building 110 Building 500 Stanford, CA 94305-2145 Stanford, CA 94305 POSITIONS Academic Employment 2020-Pr. Associate Professor, Department of Classics, Stanford University 2013-20 Assistant Professor, Department of Classics, Stanford University 2012-13 Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Art & Archaeology Centre, University of Toronto 2011-12 Visiting Research Scholar, Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University Honorary Fellowships & Awards 2014-20 Omar and Althea Dwyer Hoskins Faculty Scholar, Stanford University 2017-18 Public Engagement Fellowship, Whiting Foundation 2017-18 Internal Faculty Fellowship, Stanford Humanities Center (declined) 2016-17 McCann-Taggart Lecturer, Archaeological Institute of America 2015-16 Hellman Faculty Scholar, Hellman Fellows Fund (extended 2016-17) Other Affiliations & Visiting Positions 2020-Pr. Book Reviews Editor, Journal of Roman Archaeology 2019-Pr. Affiliated Faculty, Woods Institute for the Environment, Stanford University 2019-Pr. Affiliated Faculty, The Europe Center, Stanford University 2019-Pr. Affiliated Faculty, Mediterranean Studies Forum, Stanford University 2012-Pr. Affiliated Faculty, Institute of Nautical Archaeology 2011-Pr. Fellow, Penn Cultural Heritage Center, University of Pennsylvania 2011-Pr. Consulting Scholar, -

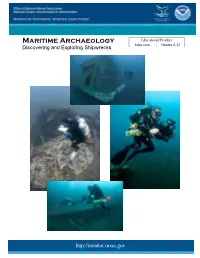

Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Educational Product Maritime Archaeology Educators Grades 6-12 Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Acknowledgement This educator guide was developed by NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. This guide is in the public domain and cannot be used for commercial purposes. Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction, without alteration, of this guide on the condition its source is acknowledged. When reproducing this guide or any portion of it, please cite NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary as the source, and provide the following URL for more information: http://monitor.noaa.gov/education. If you have any questions or need additional information, email [email protected]. Cover Photo: All photos were taken off North Carolina’s coast as maritime archaeologists surveyed World War II shipwrecks during NOAA’s Battle of the Atlantic Expeditions. Clockwise: E.M. Clark, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Dixie Arrow, Photo: Greg McFall, NOAA; Manuela, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Keshena, Photo: NOAA Inside Cover Photo: USS Monitor drawing, Courtesy Joe Hines http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Monitor National Marine Sanctuary Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and exploring Shipwrecks _____________________________________________________________________ An Educator -

An Appreciation of an Archaeological Life: Creighton Gabel, 1931-2004 Author(S): James Wiseman Source: Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol

An Appreciation of an Archaeological Life: Creighton Gabel, 1931-2004 Author(s): James Wiseman Source: Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 29, No. 1/2 (Spring, 2002 - Summer, 2004), pp. 1-5 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3181481 Accessed: 31-07-2018 16:52 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Field Archaeology This content downloaded from 128.197.33.210 on Tue, 31 Jul 2018 16:52:07 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 1 An Appreciation of an Archaeological Life: Creighton Gabel, 1931-2004 Creighton Gabel, Editor of the Journal of Field Archaeology high school Creighton attended Muskegon Junior College from 1986 to 1995 and co-founder of the Department ofAr- for a year before transferring to the University of Michigan chaeology at Boston University, died February 22, 2004, in at Ann Arbor in order to study archaeology. Since there Vero Beach, Florida, after an extended battle with cancer. He was no archaeology department at the university, the dean's was 72. office first placed him in the Classics Department where he studied classical archaeology for a year, but because his in- In his thirty-three-year career at Boston University, terest was more in prehistory, as a junior he changed his Creighton Gabel participated in the creation of two acade- major to anthropology. -

Classical Archaeology and Ancient History

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Board of the Faculty of Classics Board of the School of Archaeology Classical Archaeology and Ancient History Finals Handbook 2012 This handbook applies only to those taking the examination in the Final Honour School of Classical Archaeology and Ancient History in 2014 Faculty of Classics Ioannou Centre for Classical & Byzantine Studies 66 St Giles’ Oxford OX1 3LU www.classics.ox.ac.uk Dates of Full Terms Trinity 2012: Sunday 22 April – Saturday 16 June 2012 Michaelmas 2012: Sunday 7 October – Saturday 1 December 2012 Hilary 2013: Sunday 13 January – Saturday 9 March 2013 Trinity 2013: Sunday 21 April – Saturday 15 June 2013 Michaelmas 2013: Sunday 13 October – Saturday 7 December 2013 Hilary 2014: Sunday 19 January – Saturday 15 March 2014 Trinity 2014: Sunday 27 April – Saturday 21 June 2014 Data Protection Act 1998 You should have received from your College a statement regarding student personal data, including a declaration for you to sign indicating your acceptance of that statement. You should also have received a similar declaration for you to sign from the Faculty. Please contact your College’s Data Protection Officer or the Classics Faculty IT Officer, (whichever is relevant) if you have not. Further information on the Act can be obtained at www.admin.ox.ac.uk/councilsec/dp/index.shtml. 1 Introduction 1. This handbook offers advice and information on the CAAH Finals Course, but the official prescription for the syllabus will be printed in Examination Regulations 2012, which will appear before the beginning of Michaelmas Term. We have tried to make the information in this handbook accurate, but if there are discrepancies, Examination Regulations is the final word. -

Maquetación 1

J. M. Álvarez T. Nogales I. Rodà (Eds.) ACTAS XVIII Congreso Internacional Arqueología Clásica PROCEEDINGS XVIII TH International Congress of Classical Archaeology VOL. I CENTRO Y PERIFERIA EN EL MUNDO CLÁSICO CENTRE AND PERIPHERY IN THE ANCIENT WORLD 01 Primeras Páginas VOLUMEN 1_M 04/08/15 17:29 Página 4 Editores Editors José María Álvarez Martínez Trinidad Nogales Basarrate Isabel Rodà de Llanza Coordinación editorial Editorial Coordination Departamento de Investigación del Museo Nacional de Arte Romano María José Pérez del Castillo Nova Barrero Martín Elisabeth Fragoso Pulido Edita Edited © Museo Nacional de Arte Romano Mérida, 2014 ISBN: 978-84-617-3697-3 Vol. 1: 978-84-606-7624-9 Vol. 2: 978-84-606-7949-3 Depósito Legal Legal Deposit BA-722-2014 Maquetación e impresión Layout and printing Artes Gráficas Rejas (Mérida) Diseño de la imagen e identidad gráfica del CIAC CIAC’s Design and graphic identity Ceferino López Actividad subvencionada por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad en el marco del Subprograma Técnico de Apoyo PTA20011-5582-T a la Fundación de Estudios Romanos Actividad subvencionada por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad en el marco del Subprograma de Acciones Complementarias a Proyectos de Investigación Fundamental no Orientada 2011 (HAR 2011-14642-E) Grupo de Estudios del Mundo Antiguo (EMA), HUM-016 Consejería de Economía, Competitividad e Innovación del Gobierno de Extremadura El texto y las opiniones expresadas en este volumen son de exclusiva responsabilidad de los autores The text and the opinions expressed in this volume are the exclusive responsibility of the authors 01 Primeras Páginas VOLUMEN 1_M 04/08/15 13:21 Página 9 Índice / Contents Vol.I 35 Presentaciones / Presentations CONFERENCIA INAUGURAL / INAUGURAL CONFERENCE 47 La evolución de la arqueología clásica en Hispania durante los últimos veinte años. -

Meeting Program

Supplement to Paleopathology Newsletter PALEOPATHOLOGY ASSOCIATION SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM THIRTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING (North America) 7-8 MARCH, 2006 ANCHORAGE, ALASKA 2 33rd Annual Meeting (North America), 2006 PALEOPATHOLOGY ASSOCIATION 33rd Annual North America Meeting March 7 & 8, 2006 Anchorage, Alaska SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM TUESDAY MARCH 7TH Morning Session (9am to 12 noon): Workshop Standardizing the Standards: Computerized Documentation of Skeletal Pathology at the Smithsonian Institution (Stephen Ousley, J. Christopher Dudar, Erica Jones, Marilyn London, Gwyn Madden, Dawn Mulhern, and Cynthia Wilczak) 12-1:20pm: Let’s Do Lunch, Snow Goose Restaurant Afternoon Session I (1.30pm To 3.00pm) Chair: Dr. Christine D. White 1.30pm Announcements and session opening 1.45pm Charlotte Roberts and Sarah Ingham - Qualitative Analysis of Published Research Using aDNA Analysis to Diagnose Disease in Human Remains from Archaeological Sites: Potential and Problems to Address 2.00pm Etty Indriati and Teuku Jacob - The Dentition of the Rampasasa Pygmy and the Liang Bua Remains, Flores 2.15pm Martin Smith and Megan Brickley - “As Many Arrows Loosed Several Ways Come to One Mark” (Shakespeare) – Improving Identification of Lithic Projectile Trauma through Experimentation 2.30pm Heather Gill-Robinson and Jonathan Elias - The Palaeopathology of Pesed and Ta-Irty: Using Image Analysis to Examine and Interpret Two Wrapped Mummies from Ptolemaic Akhmim 2.45pm Niels Lynnerup - Bog Body (Pseudo) Pathology 3.00pm Break for Refreshments Afternoon Session II (3.50pm To 4.45pm) Chair: Pat Lambert 3.15pm Pia Bennike - The Variation of Bone Changes in Syphilitic Skulls 3.30pm Piers D. Mitchell and Rebecca Redfern - Diagnostic Criteria for Developmental Dislocation of the Hip in Human Skeletal Remains 3:45pm Simon Mays - Age at Occurrence and Prevalence of Spondylolysis in an English Mediaeval Population 4:00pm Tanya von Hunnius - Paleohistopathology of Faunal Remains 4:15pm T. -

Eleni Hasaki

1/9 ELENI HASAKI Associate Professor, School of Anthropology and Department of Classics Director, Arizona in the Aegean Study Abroad Program President, Archaeological Institute of America, Tucson and Southern Arizona Society The University of Arizona www.classics.web.arizona.edu/hasaki RESEARCH INTERESTS ________________________________________________________________________ Mediterranean Pottery Technology, Experimental Archaeology, Ethnoarchaeology Craft Technology and Apprenticeship in Classical Antiquity Economics of Space in Mediterranean Craft WorKshops GreeK and Roman Art and Archaeology Museum Studies and Archaeological Ethics HIGHER EDUCATION ________________________________________________________________________ 2002 Ph.D. in Classics, Classics Department, University of Cincinnati Thesis: Ceramic Kilns in Ancient Greece: Technology and Organization of Ceramic Workshops 1995 M.A. in Classics, Classics Department, University of Cincinnati Thesis: Temenos: Delimiting Sacred Space 1992 B.A. in Archaeology and Art History (summa cum laude), History and Archaeology Department, University of Athens, Greece EMPLOYMENT ________________________________________________________________________ At the University of Arizona 2009– pres. Associate Professor of Anthropology, School of Anthropology Associate Professor of Classical Archaeology, Department of Classics 2002– 2009 Assistant Professor of Classical Archaeology, Department of Classics 2002– pres. Affiliated faculty: School of Art, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of Arizona -

Nautical Archaeology Program Began Offering a Master of Science in Maritime Archaeology and Conservation

NAUTICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Master of Science in Maritime Archaeology and Conservation In the Fall semester of 2015, the Department of Anthropology’s Nautical Archaeology Program began offering a Master of Science in Maritime Archaeology and Conservation. The Nautical Archaeology Program at Texas A&M is the oldest and one of the largest master and doctoral degree granting programs of its type in the world. The M.S. degree maintains our traditional focus on ships and seafaring around the world and throughout time, as well as the fundamentals of archaeological artifact conservation. Further specialized training in maritime archaeology emphasizes technical skills required in a variety of professional areas. The M.S. is designed to prepare students for employment in maritime museums, cultural resource management firms, (including companies working with the offshore oil industry), and federal, state, or similar government agencies. Students in the M.S. program will benefit from the research opportunities and internships available through Texas A&M University’s Center for Maritime Archaeology and Conservation (CMAC), and the university-affiliated Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA). The program is open to a limited number of students, selected on a competitive basis. How to Apply For more information about how to apply and current deadlines, please visit: http://anthropology.tamu.edu/html/graduate-admission.html Required Courses Courses ANTH605 Conservation of Archaeological Resources I (4 credit hours) ANTH608 Skills in Maritime Archaeology (3