Construction Skills Gap Analysis for the the Marches LEP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walsall College 2019-20 Access and Participation Plan

Walsall College 2019-20 Access and Participation Plan Assessment of current performance Walsall is the thirtieth most deprived local authority ward in the UK, with below average levels of employment and a high number of residents (30%) who are economically inactive, compared with the West Midlands (24.9%) and UK averages (22.3%). Walsall College stands out as a ‘beacon of hope’ within the Black Country area, and is proud to inspire our students to increase their aspirations and life goals. A recent study from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows Walsall in the top four towns in England with the greatest share of the most deprived households. Walsall is the eighth most deprived town in terms of education. The work the College does is vital to the regeneration of the greater Walsall area. Walsall has significantly lower qualifications within its population, when compared with England and Wales. The number of pupils leaving school without five GCSEs is 3% higher than the national average, at 50.8%. Of the 3,477 16-18 students starting in September 2016, over 50% had either no maths or English GCSE at grade C or above. The percentage of Walsall residents with a level 4 qualification has improved from 18.2% (in 2010) to 24.3% (in 2016), but is still 13% behind the national average. These statistics are at the heart of our Widening Participation Strategy. Socio-economic factors, whether measured in terms of family income, occupational classification or neighbourhood, remain a key factor of educational attainment at school level and access to Higher Education (HE) or Higher Apprenticeships. -

The Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2004

EM NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOR WALES STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. (W. ) EDUCATION, WALES The Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2004 EXPLANATORY NOTE (This note is not part of the Order) This Order lists the name of every body which is not a recognised body within section 216(4) of the Education Reform Act 1988 but which either— (a) provides any course which is in preparation for a degree to be granted by such a recognised body and is approved by or on behalf of that body; or (b) is a constituent college, school, hall or other institution of a university which is such a recognised body. Every university, college or other body that is authorised by Royal Charter or by or under Act of Parliament to grant degrees and every other body for the time being permitted by these bodies to act on their behalf in the granting of degrees, is a recognised body. The Order updates and replaces the list of bodies contained in the Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2002, which is revoked. There are omitted from the Schedule to this Order a number of bodies previously within the list but which no longer provide courses that are approved by or on behalf of a recognised body. The Schedule includes a number of bodies that were not previously within the list but which now provide courses that are approved by or on behalf of a recognised body and incorporates other minor amendments and name changes. EM STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. (W. ) EDUCATION, WALES The Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2004 Made 2004 Coming into force 1 December 2004 In exercise of the powers conferred on the Secretary of State by section 216(2) of the Education Reform Act 1988(1) and now vested in the National Assembly for Wales(2) the National Assembly for Wales makes the following Order: Citation, commencement, application and revocation 1. -

Ofs 2018.06 Annex A: 2019-20 Access And

Walsall College 2019-20 Access and Participation Plan Assessment of current performance Walsall is the thirtieth most deprived local authority ward in the UK, with below average levels of employment and a high number of residents (30%) who are economically inactive, compared with the West Midlands (24.9%) and UK averages (22.3%). Walsall College stands out as a ‘beacon of hope’ within the Black Country area, and is proud to inspire our students to increase their aspirations and life goals. A recent study from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows Walsall in the top four towns in England with the greatest share of the most deprived households. Walsall is the eighth most deprived town in terms of education. The work the College does is vital to the regeneration of the greater Walsall area. Walsall has significantly lower qualifications within its population, when compared with England and Wales. The number of pupils leaving school without five GCSEs is 3% higher than the national average, at 50.8%. Of the 3,477 16-18 students starting in September 2016, over 50% had either no maths or English GCSE at grade C or above. The percentage of Walsall residents with a level 4 qualification has improved from 18.2% (in 2010) to 24.3% (in 2016), but is still 13% behind the national average. These statistics are at the heart of our Widening Participation Strategy. Socio-economic factors, whether measured in terms of family income, occupational classification or neighbourhood, remain a key factor of educational attainment at school level and access to Higher Education (HE) or Higher Apprenticeships. -

Managing Colleges Into the Next Century. Coombe Lodge Report. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 378 358 CE 067 949 AUTHOR Brace, Diane; And Others TITLE Managing Colleges into the Next Century. Coombe Lodge Report. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England). REPORT NO ISSN-0305-8441 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 78p. AVAILABLE FROMStaff College, Coombe Lodge, Blagdon, Bristol BS18 6RG, England (7 pounds). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.)(120) JOURNAL CIT Coombe Lodge Report; v22 n5 1990 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Administration; Educational Objectives; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Marketing; *Partnerships in Education; *Progrpm Administration; *Strategic Planning; *Technical Institutes; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS Educational Marketing; *Great Britain ABSTRACT This document contains seven papers about managing Great Britain's further education colleges in the next century. The papers examine a wide range of administrative issues, including building on human resources investments through strategic planning, maintaining relationships with local education authorities, customer satisfaction as a marketing strategy, the potential benefits of restructuring a further education college into a flat structure in which clients are given a more active role, strategies to achieve racial/sexual equality and combat all forms of disadvantage at the administration level, and the need for further education colleges to continue adapting to economic and social changes. After a foreword by Susan Leather, the following papers are included: "Strategic Planning" (Ann Limb); "Principalship in the 1990s" (Patricia Twyman); "Marketing or Customer Care?" (Gillian Brain); "The Whole College Approach" (Rosemary Gray); "Ensuring Esteem for All in College: Aims and Objectives" (Helen Gilchrist); "Articles of Partnership" (Ethlyn Prince); and "Coming Through" (Diane Brace). Several articles included bibliographies. -

West Midlands

West Midlands Introduction The West Midlands has an area of just under 13,000 km2. Around 5.2 million people live in the region, giving a population density of 405 people per km2. This is close to the average for England, but West Midlands metropolitan county – which consists of Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton – is the second most densely populated urban area in the country after London. It has nearly 3,000 people per km2. Birmingham has just under 1 million inhabitants, making it the second largest city in the UK. Other significant urban areas are Stoke-on-Trent, Worcester, Coventry, Wolverhampton and Stafford. Economic development The economic output of the West Midlands is just around £63 billion, 8.2 per cent of the total UK GDP. Manufacturing industry is responsible for just over a quarter of employment and almost 30 per cent of GDP, the highest proportion for any region in the UK. However, the manufacturing industry is declining in favour of service industries. Unemployment in the region is above the national average at 5.9 per cent. The total income of higher education institutions in the region is over £990 million per year. Higher education provision There are 12 higher education institutions in the West Midlands: eight universities and four higher education colleges. There are an additional 41 further education colleges with students taking higher education courses. All nine Staffordshire FECs offering HE courses have joined a funding consortium of 12 institutions led by Staffordshire University. The higher education student population is over 127,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) students. -

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

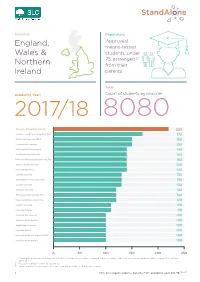

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Professional Development Networks Summer Term 2014/15

Professional Development Networks Summer Term 2014/15 BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGERS COLLEGE HE CLERKS ESTATES AND SUSTAINABILITY HEADS OF SPORT GOVERNORS FINANCE DIRECTORS IT MANAGERS HR MANAGERS INTERNATIONAL MARKETING & PRESS OFFICERS PRINCIPALS’ FORUM PROCUREMENT EFFICIENCY FORUM MIS MANAGERS LLDD QUALITY, EXCELLENCE & INNOVATION Our Professional Development Networks are free to attend for all staff in our member colleges. Network meetings provide a forum for professional exchange with colleagues, receive relevant updates from key external partners and AoC, support the exchange of good practice, and act as a springboard for collaborative development projects between colleges. NETWORKING OPPORTUNITIES REGIONAL UPDATES SHARE BEST PRACTICE COLLABORATION SHARING EXPERTISE NATIONAL UPDATES COLLEGE CASE STUDIES COLLEGE TOURS PEER SUPPORT TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES POLICY UPDATES COMPARE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES HEAR FROM EXPERTS Forthcoming Network Dates Curriculum and Quality College HE 9 June 2015 | Heart of Worcestershire College: Worcester Campus Heads of Sport 4 June 2015 | Sandwell College LLDD 24 June 2015 | Dudley College Quality, Excellence & Innovation 19 May 2015 | Heart of Worcestershire College: Redditch Campus Business Development Business Development Managers 20 May 2015 | North Warwickshire and Hinckley College: Nuneaton and Marketing Campus International 14 May 2015 | Warwickshire College Group: Rugby College Marketing & Press Officers 10 June 2015 | Shrewsbury College of Arts and Technology Leadership and Principals’ Forum: 10am -

Regional Governance Newsletter Spring Issue 2017

Regional Governance Newsletter Spring Issue 2017 elcome to the AoC West Midlands Governance WNewsletter for the spring term. This issue includes information about events we have run in the region, and up and coming activity for those involved in governance. We’ve also included articles and information about resources and best practice. In this edition: • A round up of national and regional governance news and forthcoming events • Top twelve tips on lesson observation for governors • A letter from your new AoC WM Governors’ Council representative, John Bolt • Links to resources National and regional governance news National Activity webinars aligned to the ICSA Level 6 Advanced Certificate in Corporate Governance, all of which will be underpinned by online support. National Leaders of Governance – limited funding remains for We will be contacting all FE clerks before the end of March with further colleges details and a self assessment questionnaire to identify their needs and to help shape the programme content. Limited funding remains for colleges to access support from the current National Leaders of Governance (NLG) programme. Regional Activity Consultancy support is available for chairs of governors, governance professionals and boards of governors on a range of subjects including We have continued to deliver our regular regional programme of Saturday area review implementation and Ofsted preparation. workshops and weekday networks, together with additional project activity supported by ETF. There is no charge to colleges as the programme is funded by The Education and Training Foundation (ETF). Introduction to College Funding and Financial Accountability Colleges that have received support in previous years are able to apply Steve Sawbridge, AoC WM Regional Director, and Peter Merry Finance again in this new round of funding. -

Powering Your Future with University Level Courses 2021/22

2021/22 STAY LOCAL GO FURTHER POWERING YOUR FUTURE WITH UNIVERSITY LEVEL COURSES ACCESS TO HE • HIGHER LEVELS COURSES HIGHER LEVEL/DEGREE APPRENTICESHIPS 5 REASONS TO STUDY SPENDHERE LESS Study our HNC/D and top-up courses at a fraction of the price of university with no compromise on quality. ACHIEVE MORE Our close industry links will help you get the skills that employers are looking for and put you on course to the career you want. FANTASTIC FACILITIES That’s how OFSTED - as well as our students - rate Walsall College’s campuses. SMALL CLASS SIZES Our lessons are taught in small classes increasing the one-to-one support from your lecturer. 3 YEARS = 3 QUALIFICATIONS You can progress from a number of our HNC programmes, all the way to degree level. 2 WELCOME Jatinder Sharma OBE ... to Walsall College. We are successfully Principal and Chief Executive, registered with the Office for Students (OfS) Walsall College and members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). With our high quality yet affordable route to degrees, we make it our mission to boost your job prospects and earning potential. If it’s a successful career you want, we have a wide range of courses designed with industry input and taught by expert tutors to give you the skills that employers tell us they want. Read some of our former student stories throughout this guide, and you’ll see for yourself the emphasis we place on giving students an advantage in the world of work. There’s never been a better time to join us. -

Procurement Efficiency Forum Minutes

Procurement Efficiency Forum Date: Wednesday 12 November 2014 Time: 10.00 – 1.00 pm Venue: Stafford College Minutes Present Apologies Bev Eastgate – Stratford upon Avon College Adrian Durnell – Walford & North Shropshire Corinna Marsh - Birmingham Metropolitan College College Alan Lynes – Heart of Worcestershire College Deborah Evans – Stafford College Dave Candlin - Walford & North Shropshire Louise Hollinshead - Stafford College College Roger Bevan – Warwickshire College Group Fiona Yardley - BMETC Sara King – Association of Colleges West Frank Adams – Dudley College Midlands Gita Chauhan – Solihull College Sue Perry - City of Wolverhampton College & Helen Daniel – Stafford College Walsall College Russ Bevan – Herefordshire & Ludlow Yasmin Byrne - Association of Colleges West College Midlands Sandra Buttigieg – King Edward VI College Nuneaton Guest speaker Karen Edmeads - Crescent Purchasing Consortium PART A – PRESENTATIONS 1. WELCOME, INTRODUCTIONS AND APOLOGIES Sara welcomed everyone to the meeting and noted the apologies received. Sara thanked Deborah for hosting the meeting. Sara wanted to formally thank Pat Eagle for her contribution to these networks and wish her the best of luck in her new role. Housekeeping was advised by Deborah. 2. OVERVIEW OF PROCUREMENT FROM HOST COLLEGE Deborah provided the group with an update on procurement at Stafford College. Since Pat Eagle’s departure, the college currently do not have a Procurement Officer. Procurement activities: . Re-tendered insurance. Ran a mini tender for grounds maintenance contract through CPC to look after the college and football grounds. Tendered and awarded a contract for uniforms. During the summer the college implemented ID cards and a cashless system. ID cards are linked to Wisepay. New tills are in place in the canteen to enable this facility and IT team were heavily involved. -

237 Colleges in England.Pdf (PDF,196.15

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 3 February 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St. -

WMREDI Policy Briefing Series May 2021 Priorities for Up-Skilling and Re

WMREDI Policy Briefing Series May 2021 Priorities for up-skilling and re-skilling: what role can and should universities play? Abigail Taylor, Anne Green and Sara Hassan Summary and policy recommendations Universities and colleges in the West Midlands are contributing considerably to up-skilling and re-skilling through developing future sectoral skills, piloting new ways of learning, supporting graduate employability, addressing access to higher education (HE) barriers, developing pathways between further education (FE) and HE, introducing applied higher-level skills development initiatives and working with regional governance stakeholders. Strengthening partnership working across universities and regional stakeholders is crucial to effective up-skilling and re-skilling over the next decade. Key skills-focused partnership opportunities for universities relate to developing analysis of skills needs in local areas, improving support for graduates given the challenging labour market caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, better linking skills to innovation and developing higher level skills through regional investment and R&D and innovation activities. The research identifies 12 key short- and long-term priorities for universities and other regional stakeholders to expand their role in up-skilling and re-skilling. They include simplifying progression routes between FE and HE. 1 Introduction This briefing summarises findings from a research project examining the role of universities in skills and regional economic development. It identifies key short and medium-term priorities for the up-skilling and re-skilling of school leavers, graduates and existing employees in the West Midlands. It analyses the current and potential future role of universities within this. Based on analysis of 22 interviews conducted in winter/spring 2020/2021 with universities and selected colleges in each Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) area in the West Midlands Combined Authority area, as well as their partner organisations, it contrasts experiences across the various universities.