Read the Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYC Weekend Picks | Newsday

2/21/2020 NYC weekend picks | Newsday TRAVEL NYC weekend picks Updated February 18, 2020 9:41 AM Here are our picks for what to see and do in the city this weekend. Watch puppets challenge the malaise of life Credit: Liz Maney You've got to hand it to The BoxCutter Collective, a puppet troupe that deviates from the typical felt hand creatures. In its latest offering "Everything Is Fine: A Children's Show for Scared Adults Living in a Scary World," the group skewers city life, basic life and paranoia with gut-punch comedy. WHEN | WHERE 8 p.m. Feb. 21, Jalopy Theater, 315 Columbia St., Brooklyn INFO $15; 718-395-3214, jalopytheatre.org Take a cannoli-making workshop Credit: Allison Scola | Experience Sicily Perhaps one of the underrated moments in the life of a New Yorker is that rst time one bites into a cannoli. The Italian pastry's taste is so immediate, yet it's not so easy to make. This session with cannoli connoisseur Allison Scola and Sicilian pastry chef Giusto Priola is intended to give guests the scoop on how to craft these yummies a mano. WHEN | WHERE 1:30 p.m. Feb. 22; Cacio e Vino, 80 Second Ave., Manhattan INFO $75, $45 children; 646-281-4324, experiencesicily.com https://www.newsday.com/travel/nyc-weekend-picks-our-best-bets-for-what-to-do-in-the-city-1.6813771 1/10 2/21/2020 NYC weekend picks | Newsday Big dance, big beats and big hair Credit: Newsday/Rob Rich | SocietyAllure.com While mathematically impossible to prove, this event billed as "New York's Largest Dance Party" can certainly boast lots of reasons to get up and boogie. -

“Unthinkable” a History of Policing in New York City Public Schools & the Path Toward Police-Free Schools

“Unthinkable” A History of Policing in New York City Public Schools & the Path toward Police-Free Schools Despite being named “unthinkable” by officials in Today, there are 5,322 School Safety Agents and 189 the 1950s, for more than two decades the New York uniformed police officers budgeted for the NYPD’s City Police Department (NYPD) has controlled School Safety Division. Over the last decade advocates policing inside the City’s public schools. Much has have pointed out that our School Safety Division is been written about the 1998 transfer of school safety larger than the police departments of Washington DC, authority from the school system to police under Dallas, Boston, or Las Vegas, and outnumbers the former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, but very little about Department of Education’s staffing of school guidance what accelerated that process or the landscape that counselors and social workers.3 preceded it. These are not the only police in schools. Most police This report provides a condensed political history of activity in schools is carried out by police officers policing and schooling in New York City, and offers a outside of the control of the School Safety Division. For frame for using this history to move forward a future example, in 2018, 74% of all school-based arrests were of police-free schools. This overview collects popular conducted by additional police in and around our reporting since the early 1900s, chronicling the schools – either a Detective from the Detective Bureau shifting of school safety – referring at times to police or a Patrol Officer.4 officers assigned to targeted schools, and at other times to “security aides” employed by the Board of This report also documents the ballooning budget Education (BOE). -

2018 Annual Report

A Message From Our CEO Dear Friends, up driving parents to exercise their voices. And there’s Erin Einhorn’s series, produced in partnership with Bridge Magazine, about a single I’m so proud of what Chalkbeat accomplished in 2018. middle-school classroom in Detroit that typifies the consequences of the city’s incredibly high student mobility rate (in that single class of 31 We told more and better stories in our communities, and in more students, the group had attended 128 schools among them by the time communities. (Hello, Newark and Chicago!) they reached eighth grade). We launched our first-ever listening tour, working with community And I’ve only named only a few. groups that are often disenfranchised to ask the question, What’s missing from your city’s education story? While we’re proud of what we’ve accomplished, we also know our work is far from complete. There are still too many public meetings We created our first-ever membership program, giving our readers new we can’t attend, too many communities without any education press, ways to help build our community and to engage with our reporting. and too many stories left untold. We have made our business model stronger every year, but we still have more work to do to guarantee our We continued to add “boots on the ground” reporters as other local sustainability long into the future. newsrooms suffered devastating cuts. Our 34-person newsroom produced 2,412 original stories in 2018. And yet 2018 tells us that we are moving in the right direction. -

The Moments That Matter Annual Report: July 2012–June 2013 BOARD of TRUSTEES Honorary Board

The MoMenTs ThaT MaTTer annual reporT: July 2012–June 2013 BOARD oF TrusTees honorary BoarD Herb Scannell, Chair* Kate D. Levin, ex officio Peter H. Darrow President, BBc WorldWide america commissioner, neW york city dePartment senior counsel, oF cultural aFFairs cleary gottlieB steen & hamilton, llP Cynthia King Vance, Vice Chair*, Chair† advanced strategies, LLC Anton J. Levy Eduardo G. Mestre managing director, chairman, gloBal advisory, Alexander Kaplen, Vice Chair* general atlantic LLC evercore Partners executive, time Warner Joanne B. Matthews Thomas B. Morgan John S. Rose, Vice Chair† PhilanthroPist senior Partner and managing director, Lulu C. Wang the Boston consulting grouP Bethany Millard ceo, tuPelo caPital management, LLC PhilanthroPist Susan Rebell Solomon, Vice Chair† retired Partner, Richard A. Pace neW YORK puBlIC raDIo senIor sTaFF mercer management consulting executive vice President, Bank oF neW york mellon, retired Laura R. Walker Mayo Stuntz, Vice Chair† President and ceo memBer, Pilot grouP Ellen Polaner Dean Cappello Howard S. Stein, Treasurer Jonelle Procope chieF content oFFicer managing director, gloBal corPorate President and ceo, and senior vice President and investment Bank, citigrouP, retired aPollo theater Foundation Thomas Bartunek Alan G. Weiler, Secretary Jon W. Rotenstreich vice President, PrinciPal, managing Partner, Planning and sPecial ProJects Weiler arnoW management co., inc. rotenstreich Family Partners Thomas Hjelm Laura R. Walker, President and CEO Joshua Sapan chieF digital oFFicer and vice President, neW york PuBlic radio President and ceo, amc netWorks Business develoPment Jean B. Angell Lauren Seikaly Margaret Hunt retired Partner and memBer, Private theater Producer and actress vice President, develoPment client service grouP, Bryan cave Peter Shapiro Noreen O’Loughlin Tom A. -

December 14, 2020 Mayor Bill De Blasio City Hall New York, NY

STATE OF NEW YORK OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL LETITIA JAMES ATTORNEY GENERAL December 14, 2020 Mayor Bill de Blasio City Hall New York, NY 10007 NYC Council Speak Corey Johnson City Hall Office New York, NY 10007 Dear Mayor de Blasio and Council Speaker Johnson: I am writing today about the need for major reform in the way New York City conducts its annual tax lien sale. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have repeatedly called on the City to delay the tax lien sale and to remove small homes from the lien sale list, at least until the end of the pandemic emergency. Since then, the Governor issued a series of executive orders suspending the City’s authority to sell tax liens, a decision that I strongly supported. The decision to delay the 2020 New York City lien sale was a lifeline for struggling homeowners who fell behind on their tax and water bills. At a time of escalating unemployment and food insecurity, delaying the sale saved thousands of families from further anguish and anxiety, and prevented the continued destabilization of neighborhoods that are battling the health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The delay was also effective in allowing thousands of property owners to enter into payment plans with the City and thus be removed from the lien sale list. The 2020 lien sale list now includes fewer properties than any year in recent memory, which is a great a success. I thank you both, along with councilmembers and administration staff, for working so hard to reach homeowners at this difficult time. -

WASHINGTON, D. C.: Essays on the City Form of a Capital

WASHINGTON, D. C.: Essays on the City Form of a Capital by George Kousoulas Bachelor of Architecture University of Miami Coral Gables, Florida 1982 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE, 1985 @ George Kousoulas 1985 The Author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part Signature of the autho . eorgeG osua rtment of Architecture May 10, 1985 Certified by Julian Beinart Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I I ~ I ~ D..~i- \j WWJuChairmanlia ear Departmental Committee for Graduate Students JUN 0 31985 1 otCtj 2 WASHINGTON, D.C.: Essays on the City Form of a Capital by George Kousoulas Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 10, 1985 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT This thesis is an exploration of the city form of Washington, D.C. through four independent essays. Each essay examines a different aspect of the city: its monumentality as determined by its relationship with the nation it governs, the linear network of its plan, the 'objectness' of its principal buildings, and finally, the signifigance of nature. Their structure and the manner in which they view the city are tailored to their respective topics. Together they represent a body of work whose intent is to explore those issues which distinguish Washington. The premise for this approach is a belief that cities should be understood for what they are, not only for what they are like or what they are not. -

Middle School Survey 2019

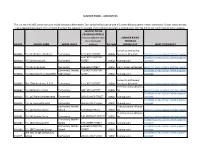

MIDDLE SCHOOL SURVEY 2019 How do you use NY State ELA and Math test scores in your admissions process? What is the application process for students without State test scores?* DISTRICT SCHOOL CONTACT INFO NOTES (including source of information) Manhattan D01 East Side Community 420 E 12th St, New State test scores are not used at all to evaluate any applicants to ESCHS. High School York, NY 10009 Middle School Directory M450S (212) 460-8467 Manhattan D01 Tompkins Square Middle 600 East 6th Street, State test scores are not used at all to evaluate any applicants to TSMS. School 3rd Floor School Website and Parent Coordinator M839 New York, NY 10009 (212) 995-1430 Manhattan D01 University Neighborhood 220 Henry Street, State test scores are not used at all to evaluate any applicants to UNMS. Middle School 3rd Floor Middle School Directory M332S New York NY 10002 (212) 267-5701 Manhattan D02 The Clinton School 10 E 15th Street, New Admissions criteria: attendance/punctuality (30%), grades (35%), ELA test M260S York, NY 10003 scores if available (17.5%), and Math test scores if available (17.5%). For (212) 524-4360 applicants without State test scores, ELA and Math grades will generally be used in place of scores. Parent Coordinator Manhattan D02 NYC Lab School 333 West 17th Street Admissions criteria: 4th grade State ELA and Math scores (if available), M312M New York, NY 10011 academic and personal behaviors, attendance/punctuality, and final 4th grade (212) 6 91-6119 report card. Students without State test scores are not penalized; in the absence of test scores, admission is based instead on the other criteria. -

Poverty and Progress in New York Xiii: the De Blasio Years

September 2019 ISSUE BRIEF POVERTY AND PROGRESS IN NEW YORK XIII: THE DE BLASIO YEARS Alex Armlovich Fellow Poverty and Progress in New York XIII: The De Blasio Years 2 Contents LIFT THE CAP WHY NEW Executive YORK Summary CITY NEEDS ....................................................... MORE CHARTER SCHOOLS3 Income Inequality ..........................................................4 Pedestrian/Traffic Safety ...............................................4 Welfare ........................................................................4 Safety in Public Housing ................................................5 Education .....................................................................5 Conclusion ...................................................................6 Endnotes ......................................................................7 Issue Brief Poverty and Progress in New York XIII: The De Blasio Years 3 Executive Summary LIFT THE CAP New York mayorWHY Bill de Blasio NEW entered YORK office CITYin January NEEDS 2014, promising MORE to “take CHARTER dead aim at the SCHOOLSTale of Two Cities … [and] put an end to economic and social inequalities that threaten to unravel the city we love.” The Man- hattan Institute’s “Poverty and Progress in New York” series has tracked the effects of de Blasio’s policies, with a particular focus on lower-income New Yorkers. This update summarizes past findings and recent developments. The MI series has focused on a number of key quality-of-life measures tied to the administration’s major policy actions or developments: income inequality and job growth, pedestrian and traffic safety and Vision Zero, welfare enrollment, crime citywide and in public housing, and ELA and math proficiency in the public schools. The administration’s record has been mixed: Income inequality is up from 2014. Vision Zero, after years of progress, has recently seen a regression, with a rising number of pedestrian traffic fatalities. Welfare enrollments have declined, following a modest initial increase through 2015. -

August 25, 2021 NEW YORK FORWARD/REOPENING

September 24, 2021 NEW YORK FORWARD/REOPENING GUIDANCE & INFORMATIONi FEDERAL UPDATES: • On August 3, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an extension of the nationwide residential eviction pause in areas experiencing substantial and high levels of community transmission levels of SARS-CoV-2, which is aligned with the mask order. The moratorium order, that expires on October 3, 2021, allows additional time for rent relief to reach renters and to further increase vaccination rates. See: Press Release ; Signed Order • On July 27, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidance for mask wearing in public indoor settings for fully vaccinated people in areas where coronavirus transmission is high, in response to the spread of the Delta Variant. The CDC also included a recommendation for fully vaccinated people who have a known exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to be tested 3-5 days after exposure, and to wear a mask in public indoor settings for 14 days or until they receive a negative test result. Further, the CDC recommends universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to schools, regardless of vaccination status See: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/vaccines/fully-vaccinated-guidance.html • The CDC on Thursday, June 24, 2021 announced a one-month extension to its nationwide pause on evictions that was executed in response to the pandemic. The moratorium that was scheduled to expire on June 30, 2021 is now extended through July 31, 2021 and this is intended to be the final extension of the moratorium. -

Washington, DC Sexuality Education

WASHINGTON, DC Washington, DC received $1,146,785 in federal funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs in Fiscal Year 2005.1 Washington, DC Sexuality Education Law and Policy Washington, DC regulations state that District public schools must provide comprehensive school health education, including instruction on human sexuality and reproduction. The instruction must be age-appropriate and taught in grades pre-kindergarten through 12. This instruction must include information on the human body, intercourse, contraception, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), pregnancy, abortion, childbirth, sexual orientation, decision-making skills regarding parenting and sexuality, and awareness and prevention of rape and sexual assault. The Superintendent of District of Columbia Public Schools is charged with ensuring that sexuality education is taught in schools and that students have a minimum proficiency in this area. Accordingly, the superintendent must provide systematic teacher trainings and staff development activities for health and physical education instructors. A list of all instructional materials for student and teacher training must be included in the list of textbooks submitted annually to the District Board of Education. The Board of Education must then approve these materials. Parents or guardians may remove their children from sexuality education and/or STD/HIV education classes. This is referred to as an “opt-out” policy. See District of Columbia Municipal Regulations Sections 2304 and 2305. Recent Legislation SIECUS is not aware of any proposed legislation related to sexuality education in Washington, DC. Events of Note District of Columbia-Based HIV/AIDS Clinic in Financial Crisis: Staff and Service Cuts Decided June 2005; Washington, DC Whitman-Walker Clinic, which provides health care and social support services to thousands of people living with HIV/AIDS in the Washington, DC area, has faced a number of financial setbacks over the past few years. -

SCHOOL SCHOOL NAME GRADE LEVELS SUMMER RISING PROGRAM ADDRESS (May Be Different Than the School Year Address)

SUMMER RISING -- MANHATTAN This is a list of all DOE elementary and middle schools in Manhattan. Each school will be paired with a Summer Rising program in their community. If your school already has a designated program, click on the link to start the registration process. If your school's program is coming soon, click the link to sign up for regular email updates. SUMMER RISING PROGRAM ADDRESS (may be different than SUMMER RISING the school year PROGRAM SCHOOL SCHOOL NAME GRADE LEVELS address) Zip Code (GRADES K-8) WHAT TO DO NEXT? University Settlement 01M015 P.S. 015 Roberto Clemente Elementary 121 EAST 3 STREET 10009 Society of New York Search for your program and then apply! 442 EAST HOUSTON Complete survey to learn when program 01M019 P.S. 019 Asher Levy Elementary STREET 10002 Coming soon! is posted 01M020 P.S. 020 Anna Silver Elementary 166 ESSEX STREET 10002 Henry Street Settlement Search for your program and then apply! Elementary, Middle, 442 EAST HOUSTON Complete survey to learn when program 01M034 P.S. 034 Franklin D. Roosevelt High School STREET 10002 Coming soon! is posted University Settlement 01M063 The STAR Academy - P.S.63 Elementary 121 EAST 3 STREET 10009 Society of New York Search for your program and then apply! The Educational Alliance, 01M064 P.S. 064 Robert Simon Elementary 600 EAST 6 STREET 10009 Inc. Search for your program and then apply! Complete survey to learn when program 01M110 P.S. 110 Florence Nightingale Elementary 285 DELANCY STREET 10002 Coming soon! is posted Complete survey to learn when program 01M134 P.S. -

All in NYC: the Roadmap for Tourism's Reimagining and Recovery

ALL IN NYC: The Roadmap for Tourism’s Reimagining and Recovery JULY 2020 01/ Introduction P.02 02/ What’s at Stake? P.06 03/ Goals P.1 0 The Coalition for NYC Hospitality & Tourism Recovery is an initiative of NYC & Company. 04/ A Program in Three Stages P.1 2 As the official destination marketing and convention and visitors bureau for the five boroughs of New York City, NYC & Company 05/ Our Campaign Platform: ALL IN NYC P.1 6 advocates for, convenes and champions New York City’s tourism and hospitality businesses 06/ Marketing Partnerships P.30 and organizations. NYC & Company seeks to maximize travel and tourism opportunities throughout the five boroughs, build economic 07/ Success Metrics P.32 prosperity and spread the dynamic image of New York City around the world. 08/ Summary P.36 09/ Acknowledgements P38 Table of Contents Table —Introduction In early 2020, as the coronavirus spread from country to country, the world came to a halt. International borders closed and domestic travel froze. Meetings, conventions and public events were postponed or canceled. Restaurants, retail stores, theaters, cultural institutions and sports arenas shuttered. Hotels closed or transitioned from welcoming guests to housing emergency and frontline workers. While we effectively minimized the spread of Covid-19 in New York City, thousands of our loved ones, friends, neighbors and colleagues have lost their lives to the virus. Our city feels, and is, changed. 2 13 We launched The Coalition for NYC our city’s story anew. As in every great New Hospitality & Tourism Recovery in May York story, the protagonists have a deep 2020 to bring together all sectors of our sense of purpose and must work to achieve visitor economy to drive and aid recovery.