Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History 251 Medieval Russia

Medieval Russia Christian Raffensperger History 251H/C - 1W Fall Semester - 2012 MWF 11:30-12:30 Hollenbeck 318 Russia occupies a unique position between Europe and Asia. This class will explore the creation of the Russian state, and the foundation of the question of is Russia European or Asian? We will begin with the exploration and settlement of the Vikings in Eastern Europe, which began the genesis of the state known as “Rus’.” That state was integrated into the larger medieval world through a variety of means, from Christianization, to dynastic marriage, and economic ties. However, over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the creation of the crusading ideal and the arrival of the Mongols began the process of separating Rus’ (becoming Russia) from the rest of Europe. This continued with the creation of power centers in NE Russia, and the transition of the idea of empire from Byzantium at its fall to Muscovy. This story of medieval Russia is a unique one that impacts both the traditional history of medieval Europe, as well as the birth of the first Eurasian empire. Professor: Christian Raffensperger Office: Hollenbeck 311 Office Phone: 937-327-7843 Office Hours: MWF 9:00–11:00 A.M. or by appointment E-mail address: [email protected] Assignments and Deadlines The format for this class is lecture and discussion, and thus attendance is a main requirement of the course, as is participation. As a way to track your progress on the readings, there will be a series of quizzes during class. All quizzes will be unannounced. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #952

Issue No. 952, 28 October 2011 Articles & Other Documents: Featured Article: U.S. Releases New START Nuke Data 1. 'IAEA Report Can Stymie Iran-P5+1 Talks' 2. German Wavers over Sale of Sub to Israel: Report 3. Armenian Nuclear Specialists Move to Iran for Better Life 4. Seoul, US Cautiously Move on 6-Party Talks 5. N. Korea Remains Serious Threat: US Defence Chief 6. Seoul, Beijing Discuss NK Issues 7. Pentagon Chief Doubts N. Korea Will Give Up Nukes 8. U.S.’s Panetta and South Korea’s Kim Warn Against North Korean Aggression 9. Pakistan Tests Nuclear-Capable Hatf-7 Cruise Missile 10. Libya: Stockpiles of Chemical Weapons Found 11. U.S. Has 'Nuclear Superiority' over Russia 12. Alexander Nevsky Sub to Be Put into Service in Late 2012 13. New Subs Made of Old Spare Parts 14. Successful Test Launch for Russia’s Bulava Missile 15. Topol Ballistic Missiles May Stay in Service until 2019 16. U.S. Releases New START Nuke Data 17. Army Says Umatilla Depot's Chemical Weapons Mission Done 18. Iran Dangerous Now, Imagine It Nuclear 19. START Treaty: Never-Ending Story 20. The "Underground Great Wall:" An Alternative Explanation 21. What’s Down There? China’s Tunnels and Nuclear Capabilities 22. Visits Timely and Important 23. Surgical Strikes Against Key Facilities would Force Iran to Face Military Reality 24. KAHLILI: Iran Already Has Nuclear Weapons Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. -

EMR 12029 Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Nevsky Russia under the Mongolian yoke / Arise, you Russian people / The Battle On Ice The Field of the Dead / Alexander’s Entry Into Pskov Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Sergeï Prokofiev EMR 12029 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + nd 1 Piccolo 2 2 Trombone + 8 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 1 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Timpani 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 1st Percussion (Xylophone / Glockenspiel / Snare Drum 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) Wood Block) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 2nd Percussion (Cymbals / Bass Drum / Triangle) 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 3rd Percussion (Tam-Tam / Tambourine / Suspended 2 B Tenor Saxophone Cymbal) 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) Special Parts 2 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 1st B Trombone 2 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 2nd B Trombone 2 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Bass Trombone 2 1st F & E Horn 1 B Baritone 2 2nd F & E Horn 1 E Tuba 2 3rd F & E Horn 1 B Tuba Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Cinemagic 39 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 Terminator (Fiedel) 5’34 EMR 12074 EMR 9718 2 Robocop 3 (Poledouris) 3’39 EMR 12131 EMR 9719 3 Rio Bravo (Tiomkin) 4’22 EMR 12085 EMR 9720 4 The Poseidon (Badelt) 4’02 EMR 12116 EMR 9721 5 Another Brick In The Wall (Waters) 4’14 EMR 12068 EMR 9722 6 Alexander Nevsky (Prokofiev) 9’48 EMR 12029 - 7 I’m Dreaming Of Home (Rombi) 4’38 EMR 12115 EMR 9723 8 Spartacus (Vengeance) (LoDuca) 4’13 EMR 12118 EMR 9724 9 The Crimson Pirate (Alwyn) 5’08 EMR 12041 EMR 9725 Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel. -

History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: the Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator

1 History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: The Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator In May 1937, Sergei Eisenstein was offered the opportunity to make a feature film on one of two figures from Russian history, the folk hero Ivan Susanin (d. 1613) or the mediaeval ruler Alexander Nevsky (1220-1263). He opted for Nevsky. Permission for Eisenstein to proceed with the new project ultimately came from within the Kremlin, with the support of Joseph Stalin himself. The Soviet dictator was something of a cinephile, and he often intervened in Soviet film affairs. This high-level authorisation meant that the USSR’s most renowned filmmaker would have the opportunity to complete his first feature in some eight years, if he could get it through Stalinist Russia’s censorship apparatus. For his part, Eisenstein was prepared to retreat into history for his newest film topic. Movies on contemporary affairs often fell victim to Soviet censors, as Eisenstein had learned all too well a few months earlier when his collectivisation film, Bezhin Meadow (1937), was banned. But because relatively little was known about Nevsky’s life, Eisenstein told a colleague: “Nobody can 1 2 find fault with me. Whatever I do, the historians and the so-called ‘consultants’ [i.e. censors] won’t be able to argue with me”.i What was known about Alexander Nevsky was a mixture of history and legend, but the historical memory that was most relevant to the modern situation was Alexander’s legacy as a diplomat and military leader, defending a key western sector of mediaeval Russia from foreign foes. -

Eisenstein's "Ivan the Terrible, Part II" As Cultural Artifact Beverly Blois

Eisenstein's "Ivan The Terrible, Part II" as Cultural Artifact Beverly Blois In one of the most famous Russian paintings, Ilya Repin's "Ivan the Terrible with his murdered son," an unkempt and wild-eyed tsar clutches his expiring son, from whose forehead blood pours forth. Lying beside the two men is a large staff with which, moments earlier, Ivan had in a fit of rage struck his heir-apparent a mortal blow. This was a poignant, in fact tragic, moment in the history of Russia because from this event of the year 1581, a line of rulers stretching back to the ninth century effectively came to an end, ushering in a few years later the smutnoe vermia ("time of trouble") the only social crisis in Russian history that bears comparison with the revolution of 1917. Contemporary Russians tell an anekdot about this painting in which an Intourist guide, leading a group of Westerners rapidly through the rooms of the Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow, comes to Repin's canvas, and wishing, as always, to put the best face on things, says, "And here we have famous painting, Ivan the Terrible giving first aid to his son." The terribilita of the sixteenth century tsar had been modernized to fit the needs of the mid-twentieth century. Ivan had been reinterpreted. In a similar, but not so trifling way, Sergei Eisenstein was expected to translate the outlines of Ivan's accomplishments into the modern language of socialist realism when he was commissioned to produce his Ivan films in 1941. While part one of his film, released in 1945, won the Stalin Prize, First Class, part two, which was very dose to release in 1946, was instead withheld. -

POSITION About the Eleventh International Youth Film

POSITION About the eleventh international youth film festival "Light to the world", dedicated to the 800th anniversary of the birth of the Holy Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky. (May 12-15, 2021, Yaroslavl oblast) (The date of the final can be changed to an indefinite period in connection with the pandemic) "I am the light of the world; he who follows Me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life" (Jn. 8: 12) 1. Objective: to promote the spiritual, moral, Patriotic and aesthetic education of the modern youth. 2. Tasks: - create an environment of healthy creative communication between children's and youth film studios and individual young film enthusiasts; - provide methodological and practical assistance to specialists working in the field of children's and youth film-making, as well as education and upbringing of children and youth; - identify and support gifted children; - identify and support young film enthusiasts and film enthusiasts who make films for children, promote traditional spiritual and moral values, patriotism, and a healthy lifestyle. 3. The organizers of the competition: The festival is co-organized by the Rybinsk diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church and the National copyright holders support Fund (Moscow). The project is being implemented in 2021 using a grant from the President of the Russian Federation for the development of civil society provided by the presidential grants Fund. The festival is supported by the administration of the Yaroslavl region and its subjects, state, commercial and public structures, PIA " Russian chronicle "(Yaroslavl), the center" Sunny " (Rybinsk), the gallery of modern Orthodox art and painting" Under the Holy cover " (Uglich), as well as the media. -

Canadian Association of Slavists Annual Conference, 2006 York University, May 27-29, 2006

CAS 2006 Canadian Association of Slavists Annual Conference, 2006 York University, May 27-29, 2006 Saturday, May 27 12:00-1:00 Annual General Meeting of the Canadian Association of Ukrainian Ethnology, VH 3003 6:00 p.m. Reception and Buffet Dinner, The Underground Restaurant. Cost: $40 per person. Sunday, May 28 1:00-3:00 p.m. Meeting of Canadian Association for Ukrainian Studies, CLH-C 3:30-5:30 p.m. Annual General Meeting of CAS, CLH-C. Monday, May 29 2:30-4:30 Joint session of Canadian Association of Slavists and Canadian Historic Association honoring Myron Momryk, Library and Archives Canada: “They Came to Canada for a Better Life”: Urban and Rural Experiences of Ukrainian- Canadians in the Interwar Period. Financial support provided by Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviations: VH – Vari Hall; CHL – Curtis Lecture Hall Saturday, May 27 I. 10:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. 1. VH 3003 Research in Progress I (Canadian Association of Ukrainian Ethnology) Chair: Natalie Kononenko, University of Alberta. Discussant: Radomir Bilash, University of Alberta. 1. Monica Kindraka-Jensen, Indiana University. How Gus Got Buried: The Role of Narratives in Shaping Ukrainian Canadian Family Identity. 2. Zenon Wasyliw, Ithaca College. Soviet Culture in the Ukrainian Village during NEP: 1921-1928. 3. Svitlana Kukharenko, University of Alberta. Searchable Sound Files online: Using Digital Technologies in Folklore Research. 2. VH 3004 Ukrainian-Canadian Experiences Chair: Roman Shiyan, University of Alberta. 1. Paul Laverdure. Eternal Memory. Achiel Delaere and Canada’s Ukrainian Catholic Church. 2. Greg Borowetz, University of Alberta. -

The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

- THE CHRONICLE OF NOVGOROD 1016-1471 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY ROBERT ,MICHELL AND NEVILL FORBES, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, D.Litt. Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE TEXT BY A. A. SHAKHMATOV Professor in the University of St. Petersburg CAMDEN’THIRD SERIES I VOL. xxv LONDON OFFICES OF THE SOCIETY 6 63 7 SOUTH SQUARE GRAY’S INN, W.C. 1914 _. -- . .-’ ._ . .e. ._ ‘- -v‘. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction (and Notes to Introduction) . vii-xxxvi Account of the Text . xxx%-xli Lists of Titles, Technical terms, etc. xlii-xliii The Chronicle . I-zzo Appendix . 221 tJlxon the Bibliography . 223-4 . 225-37 GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. THE REPUBLIC OF NOVGOROD (‘ LORD NOVGOROD THE GREAT," Gospodin Velikii Novgorod, as it once called itself, is the starting-point of Russian history. It is also without a rival among the Russian city-states of the Middle Ages. Kiev and Moscow are greater in political importance, especially in the earliest and latest mediaeval times-before the Second Crusade and after the fall of Constantinople-but no Russian town of any age has the same individuality and self-sufficiency, the same sturdy republican independence, activity, and success. Who can stand against God and the Great Novgorod ?-Kto protiv Boga i Velikago Novgoroda .J-was the famous proverbial expression of this self-sufficiency and success. From the beginning of the Crusading Age to the fall of the Byzantine Empire Novgorod is unique among Russian cities, not only for its population, its commerce, and its citizen army (assuring it almost complete freedom from external domination even in the Mongol Age), but also as controlling an empire, or sphere of influence, extending over the far North from Lapland to the Urals and the Ob. -

GRAY-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (997.1Kb)

Copyright by Travis Michael Gray 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Travis Michael Gray Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Amid the Ruins: The Reconstruction of Smolensk Oblast, 1943-1953 Committee: Charters Wynn, Supervisor Joan Neuberger Mary Neuburger Thomas Garza Amid the Ruins: The Reconstruction of Smolensk Oblast, 1943-1953 by Travis Michael Gray Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2018 Dedication Dedicated to my mother, father, and brother for their unending love and support.. Acknowledgements The following work could not have been possible without the help of many people. I am especially thankful to Dr. Charters Wynn for his valuable feedback, suggestions, and guidance throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dr. Joan Neuberger, Dr. Mary Neuburger, and Dr. Thomas Garza for reading and commenting on my work. My appreciation also goes to my friends and colleagues at the University of Texas who offered their suggestions and support. v Abstract Amid the Ruins: The Reconstruction of Smolensk Oblast, 1943-1953 Travis Michal Gray, PhD The University of Texas at Austin, 2018 Supervisor: Charters Wynn The first Red Army soldiers that entered Smolensk in the fall of 1943 were met with a bleak landscape. The town was now an empty shell and the countryside a vast wasteland. The survivors emerged from their cellars and huts on the verge of starvation. Amidst the destruction, Party officials were tasked with picking up the pieces and rebuilding the region’s political, economic, and social foundations. -

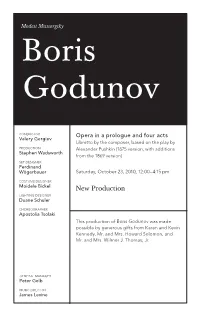

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

1 Golden Ring Tour – Part 4 Spaso-Preobrazhensky Monastery

Golden Ring Tour – Part 4 Spaso-Preobrazhensky Monastery (Yaroslav Museum-Reserve) The Transfiguration of the Saviour Cathedral was once the monastery's main cathedral. https://rusmania.com/central/yaroslavl-region/yaroslavl/sights/around-bogoyavlenskaya- ploschad/spaso-preobrazhensky-monastery-yaroslavl-museum-reserve 1 Built onto the Transfiguration of the Saviour Cathedral is the Yaroslavl Miracle-Workers Church which is dedicated to Prince Fyodor of Yaroslavl and his sons David and Konstantin. All three have since been canonised and are considered local saints of Yaroslavl. The church was built between 1827 and 1831 in the classical style and its front is decorated with six columns. The monastery’s massive belfry stands at almost 32 metres tall. The lower part of the belfry dates from the mid-16th century. This was added to in the beginning of the 19th century when another tier was built on with a dome. The structure, especially its upper tiers, was heavily damaged during the 1918 Uprising and subsequently restored in the 1920s and 1950s. In addition to the 18 bells which are part of the belfry, the Our Lady of Pechersk Church is also located inside. Tickets can be brought to enjoy great views of the historical part of Yaroslavl from the very top, which can be reached via narrow and occasionally steep staircases inside. 2 3 https://luxeadventuretraveler.com/bear- symbol-yaroslavl-gadvrussia/ As the story goes, Prince Yaroslav was sailing down the Volga River and noticed a tribe had settled on a plateau where the Volga met the Kotorsol River. The Prince immediately recognized the trading potential of the confluence and set out to take the land from the tribe. -

1 Sergei M. Eisenstein: Alexander Nevsky (1937/8) and Ivan The

1 Sergei M. Eisenstein: Alexander Nevsky (1937/8) and Ivan the Terrible Parts I and II (1942-5) The history and politics of these films are imbecile. Take the opening of Ivan I: Ivan is crowned, despite the mutterings of the ambassadors, of the boyars, and of ugly old Efrosinia, whose idiot son (he talks with his mouth full) is now debarred the succession. Noble, clean-cut sixteenth-century proletarians gatecrash the coronation, and are abashed by Ivan’s majesty. Cruel, foolish Tartar envoys from Khazan gatecrash the coronation too, and threaten Muscovy with “Moskva – malenky: Khazan – bolshoi!” They give Ivan their equivalent of Henry V’s tennis balls: a dagger with which to kill himself. He treats the gesture with apt contempt, and says that although he has never wanted war, if they want it they can have it. The noble, clean-cut proletarians cheer him, saying with delight, “The Tsar is no fool!” and one eyeballs the chief of the cruel, foolish Khazan envoys with, “Khazan – malenky: Moskva – bolshoi!” whereupon the Khazan envoy looks terribly worried … and so on. The acting is totalitarian; as if Stanislavsky had never been. Behaviouristic it isn’t, and total identification with your part is a long way off – it’s all nineteenth-century ham, in close- up – solid, semaphore acting. And not a raised eyebrow nor a rolling eye is there without 2 Eisenstein’s say-so. Few shots last more than five seconds; the rhythm is dictated, not by the actors’ instincts, but by the director’s will. Actors are not creative artists, but puppets – filmed preferably in close-up, lit from below.