1. the Nunnery of St. Mary Clerkenwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2014 Incorporating Islington History Journal

Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society Vol 4 No 3 Autumn 2014 incorporating Islington History Journal War, peace and the London bus The B-type London bus that went to war joins the Routemaster diamond jubilee event Significants finds at Caledonian Parkl Green plaque winners l World War 1 commemorations l Beastly Islington: animal history l The emigrants’ friend and the nursing pioneer l The London bus that went to war l Researching Islington l King’s Cross aerodrome l Shoreditch’s camera obscura l Books and events l Your local history questions answered About the society Our committee What we do: talks, walks and more Contribute to this and contacts heIslington journal: stories and President Archaeology&History pictures sought RtHonLordSmithofFinsbury TSocietyishereto Vice president: investigate,learnandcelebrate Wewelcomearticlesonlocal MaryCosh theheritagethatislefttous. history,aswellasyour Chairman Weorganiselectures,tours research,memoriesandold AndrewGardner,andy@ andvisits,andpublishthis photographs. islingtonhistory.org.uk quarterlyjournal.Wehold Aone-pagearticleneeds Membership, publications 10meetingsayear,usually about500words,andthe and events atIslingtontownhall. maximumarticlelengthis CatherineBrighty,8 Wynyatt Thesocietywassetupin 1,000words.Welikereceiving Street,EC1V7HU,0207833 1975andisrunentirelyby picturestogowitharticles, 1541,catherine.brighteyes@ volunteers.Ifyou’dliketo butpleasecheckthatwecan hotmail.co.uk getinvolved,pleasecontact reproducethemwithout -

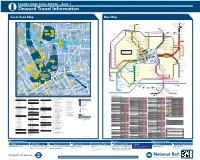

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

153 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

153 bus time schedule & line map 153 Finsbury Park Station View In Website Mode The 153 bus line (Finsbury Park Station) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Finsbury Park Station: 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Liverpool Street: 4:48 AM - 11:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 153 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 153 bus arriving. Direction: Finsbury Park Station 153 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Finsbury Park Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Liverpool Street Station (C) Sun Street Passage, London Tuesday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Moorgate Station (B) Wednesday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM 142-171 Moorgate, London Thursday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Finsbury Street (S) Friday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM 72 Chiswell Street, London Saturday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Silk Street (BM) 47 Chiswell Street, London Barbican Station (BA) Aldersgate Street, London 153 bus Info Direction: Finsbury Park Station Clerkenwell Road / Old Street (BQ) Stops: 33 60 Goswell Road, London Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Liverpool Street Station (C), Clerkenwell Road / St John Street Moorgate Station (B), Finsbury Street (S), Silk Street 64 Clerkenwell Road, London (BM), Barbican Station (BA), Clerkenwell Road / Old Street (BQ), Clerkenwell Road / St John Street, Aylesbury Street Aylesbury Street, Percival Street (UJ), Spencer Street 159-173 St John Street, London / City University (UK), Rosebery Avenue / Sadler's Wells Theatre (UL), St John Street / Goswell Road Percival Street (UJ) (P), Chapel Market (V), Penton Street / Islington St. -

—— 407 St John Street

ANGEL BUILDING —— 407 ST JOHN STREET, EC1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 THE LOCALITY 8 A SENSE OF ARRIVAL 16 THE ANGEL KITCHEN 18 ART AT ANGEL 20 OFFICE FLOORS 24 TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION 30 SUSTAINABILITY 32 LANDSCAPING 34 CANCER RESEARCH UK 36 AHMM COLLABORATION 40 SOURCES OF INSPIRATION 42 DERWENT LONDON 44 PROFESSIONAL TEAM 46 Angel Building 2 / 3 Angel Building 4 / 5 Located in EC1, the building commands the WELCOME TO heights midway between the financial hub of the City of London and the international rail THE ANGEL BUILDING interchange and development area of King’s Cross —— St. Pancras. With easy access to the West End, it’s at the heart of one of London’s liveliest historic The Angel Building is all about improving radically urban villages, with a complete range of shops, on the thinking of the past, to provide the best restaurants, markets and excellent transport possible office environment for today. A restrained links right outside. The Angel Building brings a piece of enlightened modern architecture by distinguished new dimension to the area. award-winning architects AHMM, it contains over 250,000 sq ft (NIA) of exceptional office space. With a remarkable atrium, fine café, and ‘IT’S A GOOD PLACE exclusively-commissioned works of contemporary TO BE’ art, it also enjoys exceptional views from its THE ANGEL enormous rooftop terraces. Above all, this is where This is a building carefully made to greatly reduce the City meets the West End. The Angel Building its carbon footprint – in construction and in is a new addition to this important intersection operation. -

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal July 2018 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Alison Bennett, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 2/8/18 Reviser(s): Alison Bennett Date of last revision: 31/8/18 Date Printed: Version: 2 Status: Summary of Changes: Circulation: Required Action: File Name/Location: Approval: (Signature) 2 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 5 3 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers .................................................................................. 7 4 The London Borough of Islington: Historical and Archaeological Interest ....................... 9 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Prehistoric (500,000 BC to 42 AD) .......................................................................... 9 4.3 Roman (43 AD to 409 AD) .................................................................................... 10 4.4 Anglo-Saxon (410 AD to 1065 AD) ....................................................................... 10 4.5 Medieval (1066 AD to 1549 AD) ............................................................................ 11 4.6 Post medieval (1540 AD to 1900 AD).................................................................... 12 4.7 Modern -

Finsbury Park

FINSBURY PARK Park Management Plan 2020 (minor amendments January 2021) Finsbury Park: Park Management Plan amended Jan 2021 Section Heading Page Contents Foreword by Councillor Hearn 4 Draft open space vision in Haringey 5 Purpose of the management plan 6 1.0 Setting the Scene 1.1 Haringey in a nutshell 7 1.2 The demographics of Haringey 7 1.3 Deprivation 8 1.4 Open space provision in Haringey 8 2.0 About Finsbury Park 2.1 Site location and description 9 2.2 Facilities 9 2.3 Buildings 17 2.4 Trees 18 3.0 A welcoming place 3.1 Visiting Finsbury Park 21 3.2 Entrances 23 3.3 Access for all 24 3.4 Signage 25 3.5 Toilet facilities and refreshments 26 3.6 Events 26 4.0 A clean and well-maintained park 4.1 Operational and management responsibility for parks 30 4.2 Current maintenance by Parks Operations 31 4.3 Asset management and project management 32 4.4 Scheduled maintenance 34 4.5 Setting and measuring service standards 38 4.6 Monitoring the condition of equipment and physical assets 39 4.7 Tree maintenance programme 40 4.8 Graffiti 40 4.9 Maintenance of buildings, equipment and landscape 40 4.10 Hygiene 40 5.0 Healthy, safe and secure place to visit 5.1 Smoking 42 5.2 Alcohol 42 5.3 Walking 42 5.4 Health and safety 43 5.5 Reporting issues with the ‘Love Clean Streets’ app 44 5.6 Community safety and policing 45 5.7 Extending Neighbourhood Watch into parks 45 5.8 Designing out crime 46 5.9 24 hour access 48 5.10 Dogs and dog control orders 49 6.0 Sustainability 6.1 Greenest borough strategy 51 6.2 Pesticide use 51 6.3 Sustainable use of -

JEWISH CIVILIAN DEATHS DURING WORLD WAR II Excluding Those Deaths Registered in the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney

JEWISH CIVILIAN DEATHS DURING WORLD WAR II excluding those deaths registered in the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney Compiled by Harold Pollins This list may not be used elsewhere without consent. ©Harold Pollins For a full description of the contents of this list please see the description on the list of datasets Harold Pollins acknowledges the tremendous assistance of Harvey Kaplan who collated the Glasgow deaths Date of Additional Information Surname Given Name Place of Residence Place of Death Age Spouse Name Father's Name Mother's Name Death Comments and Notes 34 Twyford Avenue, AARONBERG Esther Acton 18‐Oct‐40 40 Ralph 34 Twyford Avenue, AARONBERG Ralph Acton 18‐Oct‐40 35 Esther 39 Maitland House, Bishop's Way, Bethnal Bethnal Green Tube AARONS Betty Diane Green Shelter 03‐Mar‐43 14 Arnold In shelter accident BROOKSTONE Israel 41 Teesdale Street Tube shelter 03‐Mar‐43 66 Sarah In shelter accident in shelter accident. Light Rescue Service. Son of Mr and Mrs B Lazarus of 157 Bethnal LAZARUS Morris 205 Roman Road Tube shelter 03‐Mar‐43 43 Rosy Green Road 55 Cleveland Way, Mile MYERS Jeffrey End Tube shelter 03‐Mar‐43 6 Isaac Sophie in shelter accident 55 Cleveland Way, Mile MYERS Sophie End Tube shelter 03‐Mar‐43 40 Isaac Charterhouse Clinic, Thamesmouth, Westcliff‐ Weymouth St, Obituary Jewish Chronicle ABRAHAMS Alphonse Nathaniel on‐Sea Marylebone 17‐Sep‐40 65 Evelyn May 15.11.1940 page 6 98 Lewis Trust Buildings, injured 4 January 1945 at ABRAHAMS Benjamin Dalston Lane, Hackney German Hospital 08‐Jan‐45 56 Leah Forest Road Library 96 Tottenham Court Polish National. -

73 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

73 bus time schedule & line map 73 Stoke Newington - Oxford Circus View In Website Mode The 73 bus line (Stoke Newington - Oxford Circus) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Oxford Circus: 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM (2) Stoke Newington: 12:00 AM - 11:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 73 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 73 bus arriving. Direction: Oxford Circus 73 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Oxford Circus Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:05 AM - 11:57 PM Monday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM Stoke Newington Common (K) Tuesday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM Stoke Newington High Street (U) 128 Stoke Newington High Street, London Wednesday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM William Patten School (V) Thursday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM 37A Stoke Newington Church Street, London Friday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM Abney Park (W) Saturday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM 86 Stoke Newington Church Street, London Stoke Newington Town Hall (W) 181 Stoke Newington Church Street, London 73 bus Info Barbauld Road (S) Direction: Oxford Circus 184 Albion Road, London Stops: 33 Trip Duration: 49 min Clissold Crescent (NA) Line Summary: Stoke Newington Common (K), Clissold Crescent, London Stoke Newington High Street (U), William Patten School (V), Abney Park (W), Stoke Newington Town Green Lanes (NB) Hall (W), Barbauld Road (S), Clissold Crescent (NA), 40-41 Newington Green, London Green Lanes (NB), Newington Green (NE), Beresford Road (CA), Balls Pond Road (CB), Essex Road / Newington Green (NE) Marquess Road (CG), Northchurch Road (EH), Essex 20 Newington -

The London Gazette, Novembeb 20, 1900. 7331

THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBEB 20, 1900. 7331 OTICE is Lereby given, that the Governor at which respective offices, as well as at the office N and Company of the New River brought of the Company, all persons wishing to inspect from Chad well and Amwell to London, commonly them may do so at any time during office hours for called the New River Company, under the powers the period of one month before they are confirmed. of the Metropolis Water Act, 1852, the "Metro- —Dated this seventeenth November, 1900. polis Water Act, 1871, and the Metropolis Water By order of the Board, Act, 1897, has (subject to necessary confirmation) . MONTAGUE WATTS, Secretary. made Regulations instead of the Regulations now Office : Southwark Bridge-road, London, S.E. in force, and that the Regulations so made have been submitted to the Local Government Board TVT OTICE is here1 y given that the East London for confirmation, and that copies have been 1, JJ Waterworks Company under the powers of deposited at the offices of the Mayor, Aldermen, the Metropolis Water Act, 1852, ihe Metropolis and Commons of the city of London, the London Wa'er Act, 1871, and the Metropolis Water, Acr, County Council, the city of Westminster, the 1897, have, subject to necessary confirmation, made metropolitan boroughs of Finsbury, Islington, Regulations instead of the Regulations now in Shoreditch, Stepney, Hackney, Stoke Newington, force, and that the Regulations so made have been St. Pancras, Hampstead, and Holborn ; the submitted to the Local Government Board for Urban District Councils of Hornc-ey, Tottenham, confirmation, and that copies have been deposited and Wood Green, and at the offices of the County at the offices of the Major, Aldermen, and Com- Councils of Middlesex and Hertfordshire; at mons of the city of London, of the London County which respective offices, as well as at the office of Council, of the metropolitan boroughs of Bethnal the. -

Milliken Clerkenwell

CLERKENWELL EC1 CLERKENWELL / EC1 CEC6 Fleet Works CEC152 The Smokery CEC25 Penny Bank CEC27 Singing Britton CEC171 Barbican CEC122 John’s Gate CEC120 Corner House CEC79 Tech City CEC182 Farringdon CEC144 Smithfield CEC103 The Green CEC138 Mystery Play CEC149 Hidden Treasures CLERKENWELL - EC1 LIGHT REFLECTANCE CLERKENWELL - EC1 SPECIFICATION PERFORMANCE Colour Colour Name L Value LRV (Y) Value Construction Flammability Tufted, Textured Tip-Shear (Euroclassification EN13501:1-2002) DQR/CEC/FBS 171 BARBICAN 44.9 14.5 Face Fibre Class Bfl – s1 DQR/CEC/FBS 120 CORNER HOUSE 33.0 7.5 Universal® Fibres, solution dyed nylon 6 6 Flammability (Radiant Panel ASTM-E-648) Soil Release Class 1 DQR/CEC/FBS 140 EXMOUTH MARKET 50.7 19.0 Stainsmart® Flammability (Hot metal nut BS4790) Finished Face Weight Low radius of Char DQR/CEC/FBS 182 FARRINGDON 17.8 2.5 Design Quarter 720g/m2 Use Classification (EN1307) EC1 675g/m2 Class 33 DQR/CEC/FBS 6 FLEET WORKS 53.3 21.3 2 Finsbury Square 840g/m Static Electricity (ISO 6356) DQR/CEC/FBS 66 FONT SIZE 19.8 2.9 Gauge Pass ≤ 2.0 KV 47.2/10 cm Impact Sound (ISO 10140-3) DQR/CEC/FBS 149 HIDDEN TREASURES 50.9 19.2 Rows 34 dB 41.2/10 cm Sound absorption (ISO 354) DQR/CEC/FBS 132 INNER LONDON 44.5 14.2 CEC48 Paper Grain CEC132 Inner London CEC118 Slade’s Place CEC66 Font Size Tuft Density 0.30 (H) Class D 198 060/m2 Alpha s values DQR/CEC/FBS 229 ISLINGTON BOROUGH 21.6 3.4 Finished Pile Height 125Hz 0.03, 250Hz 0.08, 500Hz 0.54, 3.3 mm 1000Hz 0.26, 2000Hz 0.32, 4000Hz 0.45 DQR/CEC/FBS 122 JOHN’S GATE 45.4 14.8 Standard -

Buses from Stamford Hill

Buses from Stamford Hill 318 349 Ponders End Bus Garage Key North Middlesex Hospital for Southbury O Hail & Ride Ponders End High Street PONDERS END — Connections with London Underground section o Connections with London Overground Bull Lane Hertford Road R Connections with National Rail 24 hour 149 service Edmonton Green Bus Station White Hart Lane DI Connections with Docklands Light Railway Upper Edmonton Angel Corner for Silver Street Tottenham Cemetery B Connections with river boats White Hart Lane The Roundway Route 318 operates as Hail & Ride on the sections of roads marked Wood Green 476 Northumberland Park 24 hour H&R1 H&R2 67 243 service and on the map. Buses stop at any safe point along the WOOD GREEN Lansdowne Road Lordship Lane Lordship Lane High Road Shelbourne Road road. There are no bus stops at these locations, but please indicate Wood Green Shopping City The Roundway (East Arm) Lordship Lane clearly to the driver when you wish to board or alight. Bruce Grove Dowsett Road Windsor Road Turnpike Lane Elmhurst Road Hail & Ride section West Green Road Stanley Road Bruce Grove Monument Way High Road Tottenham Police Station West Green Road West Green Primary School Park View Road 24 hour 76 service West Green Road Black Boy Lane Tottenham Town Hall Monument Way Tottenham Hale Tottenham High Road Black Boy Lane Abbotsford Avenue High Road College of North East London St Ann’s Road TOTTENHAM Black Boy Lane Chestnuts Primary School St Ann’s Road Seven Sisters Road/ Seven Sisters Police Station Plevna Crescent High Road Seven Sisters -

8 BEAUTIFULLY FORMED LOFTS and HOUSES BASED in STOKE NEWINGTON Matchbox Yard, N16 Matchbox Yard, N16 WELCOME

www.matchboxyard.co.uk 8 BEAUTIFULLY FORMED LOFTS AND HOUSES BASED IN STOKE NEWINGTON matchbox yard, n16 www.matchboxyard.co.uk www.matchboxyard.co.uk matchbox yard, n16 WELCOME Matchbox Yard brings you into the hubbub of London’s hottest hot spot. MATCHBOX YARD, Now all you need to do is grow out that beard, get a tattoo and you’re home. BARRETT’S GROVE, N16 8AJ NB: Any CGIs depicted are an artist’s concept of the completed building An oasis of colour in leafy Stoke Newington, A PRIVATE DEVELOPMENT at the edge of vibrant Dalston and London’s YOUR SPACE TO LIVE, DISCOVER AND ENJOY IN LONDON’S CREATIVE HUB creative independent scene. THE BEST OF EAST LONDON internal cgis www.matchboxyard.co.uk www.matchboxyard.co.uk internal cgis A STUNNING WAREHOUSE LOFT CONVERSION INTO 8 BEAUTIFULLY DEVELOPED FLATS & HOUSES JUST OFF STOKE NEWINGTON HIGH STREET NB: Any CGIs depicted are an artist’s concept of the completed building and/or its interiors only. location www.matchboxyard.co.uk www.matchboxyard.co.uk location JUST A HOP, SKIP AND JUMP AWAY HIGHBURY & OXFORD CANARY LONDON CITY STRATFORD MOORGATE ISLINGTON CIRCUS WHARF AIRPORT EASTEASTEAST LONDONLONDONLONDONLONDON 11 14 19 33 MINS MINS MINS MINS MINS MINS THE OPTION TO RIDE WITH THE DALSTON BUZZ... When it comes to lifestyle, Dalston ups the ante, with stores selling clothes and accessories, furniture Matchbox Yard and bric-à-brac – always artfully arranged – whether classic tailored suits or on-trend vintage, rare 32a-32c Barrett’s Grove vinyl records and more, often sourced from all over the world.