Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition for Table of Contents, See Home Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

Precursors and Chemicals Frequently Used in the Illicit Manufacture of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 2017

INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL BOARD Precursors and chemicals frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances 2017 EMBARGO Observe release date: Not to be published or broadcast before Thursday, 1 March 2018, at 1100 hours (CET) UNITED NATIONS CAUTION Reports published by the International Narcotics Control Board in 2017 The Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2017 (E/INCB/2017/1) is supplemented by the following reports: Narcotic Drugs: Estimated World Requirements for 2018—Statistics for 2016 (E/INCB/2017/2) Psychotropic Substances: Statistics for 2016—Assessments of Annual Medical and Scientific Requirements for Substances in Schedules II, III and IV of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 (E/INCB/2017/3) Precursors and Chemicals Frequently Used in the Illicit Manufacture of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances: Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2017 on the Implementation of Article 12 of the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988 (E/INCB/2017/4) The updated lists of substances under international control, comprising narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and substances frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, are contained in the latest editions of the annexes to the statistical forms (“Yellow List”, “Green List” and “Red List”), which are also issued by the Board. Contacting the International Narcotics Control Board The secretariat of the Board may be reached at the following address: Vienna International Centre Room E-1339 P.O. Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria In addition, the following may be used to contact the secretariat: Telephone: (+43-1) 26060 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5867 or 26060-5868 Email: [email protected] The text of the present report is also available on the website of the Board (www.incb.org). -

Well-Known Plants in Each Angiosperm Order

Well-known plants in each angiosperm order This list is generally from least evolved (most ancient) to most evolved (most modern). (I’m not sure if this applies for Eudicots; I’m listing them in the same order as APG II.) The first few plants are mostly primitive pond and aquarium plants. Next is Illicium (anise tree) from Austrobaileyales, then the magnoliids (Canellales thru Piperales), then monocots (Acorales through Zingiberales), and finally eudicots (Buxales through Dipsacales). The plants before the eudicots in this list are considered basal angiosperms. This list focuses only on angiosperms and does not look at earlier plants such as mosses, ferns, and conifers. Basal angiosperms – mostly aquatic plants Unplaced in order, placed in Amborellaceae family • Amborella trichopoda – one of the most ancient flowering plants Unplaced in order, placed in Nymphaeaceae family • Water lily • Cabomba (fanwort) • Brasenia (watershield) Ceratophyllales • Hornwort Austrobaileyales • Illicium (anise tree, star anise) Basal angiosperms - magnoliids Canellales • Drimys (winter's bark) • Tasmanian pepper Laurales • Bay laurel • Cinnamon • Avocado • Sassafras • Camphor tree • Calycanthus (sweetshrub, spicebush) • Lindera (spicebush, Benjamin bush) Magnoliales • Custard-apple • Pawpaw • guanábana (soursop) • Sugar-apple or sweetsop • Cherimoya • Magnolia • Tuliptree • Michelia • Nutmeg • Clove Piperales • Black pepper • Kava • Lizard’s tail • Aristolochia (birthwort, pipevine, Dutchman's pipe) • Asarum (wild ginger) Basal angiosperms - monocots Acorales -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Various Terminologies Associated with Areca Nut and Tobacco Chewing: a Review

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Vol. 19 Issue 1 Jan ‑ Apr 2015 69 REVIEW ARTICLE Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review Kalpana A Patidar, Rajkumar Parwani, Sangeeta P Wanjari, Atul P Patidar Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Modern Dental College and Research Center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Kalpana A Patidar, Globally, arecanut and tobacco are among the most common addictions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Tobacco and arecanut alone or in combination are practiced in different regions Modern Dental College and Research Centre, in various forms. Subsequently, oral mucosal lesions also show marked Airport Road, Gandhi Nagar, Indore ‑ 452 001, Madhya Pradesh, India. variations in their clinical as well as histopathological appearance. However, it E‑mail: [email protected] has been found that there is no uniformity and awareness while reporting these habits. Various terminologies used by investigators like ‘betel chewing’,‘betel Received: 26‑02‑2014 quid chewing’,‘betel nut chewing’,‘betel nut habit’,‘tobacco chewing’and ‘paan Accepted: 28‑03‑2015 chewing’ clearly indicate that there is lack of knowledge and lots of confusion about the exact terminology and content of the habit. If the health promotion initiatives are to be considered, a thorough knowledge of composition and way of practicing the habit is essential. In this article we reviewed composition and various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco habits in an effort to clearly delineate various habits. Key words: Areca nut, habit, paan, quid, tobacco INTRODUCTION Tobacco plant, probably cultivated by man about 1,000 years back have now crept into each and every part of world. -

Methyleugenol (4-Allyl-1,2-Dimethoxybenzene)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL Directorate C - Scientific Opinions C2 - Management of scientific committees II; scientific co-operation and networks Scientific Committee on Food SCF/CS/FLAV/FLAVOUR/4 ADD1 FINAL 26 September 2001 Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on Methyleugenol (4-Allyl-1,2-dimethoxybenzene) (adopted on 26 September 2001) Rue de la Loi 200, B-1049 Bruxelles/Wetstraat 200, B-1049 Brussel - Belgium - Office: F101 - 6/172 Telephone: direct line (+32-2) 295.4861, switchboard 299.11.11. Fax: (+32-2) 299.4891 Telex: COMEU B 21877. Telegraphic address: COMEUR Brussels http://europa.eu.int/comm/food/fs/sc/scf/index_en.html SCF/CS/FLAV/FLAVOUR/4 ADD1 FINAL Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on Methyleugenol (4-Allyl-1,2-dimethoxybenzene) (adopted on 26 September 2001) Terms of reference The Committee is asked to advise the Commission on substances used as flavouring substances or present in flavourings or present in other food ingredients with flavouring properties for which existing toxicological data indicate that restrictions of use or presence might be necessary to ensure safety for human health. In particular, the Committee is asked to advise the Commission on the implications for human health of methyleugenol (4-allyl-1,2-dimethoxybenzene) in the diet. Introduction In 1999 methyleugenol was evaluated by the Committee of Experts on Flavouring Substances of the Council of Europe. The conclusions of this Committee were: "Available data show that methyleugenol is a naturally-occurring genotoxic carcinogen compound with a DNA-binding potency similar to that of safrole. Human exposure to methyleugenol may occur through the consumption of foodstuffs flavoured with aromatic plants and/or their essential oil fractions which contain methyleugenol. -

Botanicals for Health

PBRC 2012 Botanicals for Health Special points of interest: Cinnamon can increase insulin sensitivity Ginger can help reduce chronic diseases Lemongrass has been used against colds Olive has other healthful components other than oil Botanicals for chronic disease prevention Botanicals are phytochemicals sage, sassafras, tamarind, over the years in Europe have from plants that have an tarragon, tea, thyme, and found similar results. Cinnamon impact on human health. turmeric. These plants have Many of the plant phytochemi- specific phytochemicals that One of the healthiest diets in cals act as anti-oxidants that have been shown to kill can- the world, the Mediterranean get rid of many harmful com- cer cells, reduce diabetes risk Diet is high in fruits and vege- pounds in the body. They are and to protect blood vessels tables, healthful oils and anti-inflammatory, antimicrobi- against plaque formation. The many botanicals. Typical bo- al, antitumor, cardiovascular types and numbers of phyto- tanicals as part of the Medi- system enhancing and choles- chemicals in these and many terranean diet are garlic, on- terol lowering compounds. other botanicals is in the thou- ion, mint, lime, orange, lemon, They also influence the im- sands. fennel, basil, bay leaf, dill, mune system and act as anti- pomegranate, rosemary, sage, diabetic compounds. Many large scale studies have tarragon, and thyme. This diet shown that plant phytochemi- is also high in olive oil, red We consume many botanicals cals offer protection against wine and tomatoes. The Medi- as part of our regular diet that cancer and cardiovascular terranean diet is particularly offer health benefits beyond disease. -

For Review Only

International Wound Journal Essential oils and met al ions as alternative antimicrobial agents: A focus on tea tree oil and silver Journal:For International Review Wound Journal Only Manuscript ID IWJ-15-430.R1 Wiley - Manuscript type: Original Article Keywords: Antimicrobial, Silver, Tea Tree Oil, Wound infection The increasing occurrence of hospital infections and the emerging problems posed by antibiotic resistant strains contribute to escalating treatment costs. Infection on the wound site can potentially stall the healing process at the inflammatory stage, leading to the development of acute wounds. Traditional wound treatment regime can no longer cope with the complications posed by antibiotic resistant strains; hence there is a need to explore the use of alternative antimicrobial agents. In recent research, pre- antibiotic compounds, including heavy metal ions and essential oils have been re-investigated for their potential use as effective antimicrobial Abstract: agents. Essential oils have been identified to have potent antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and other beneficial therapeutic properties. Similarly, heavy metal ions have also been used as disinfecting agents due to their broad spectrum activities. Such activities is contributed by reactive properties of the metal cations, which allows the ions to interact with many different intracellular compounds, thereby resulting in the disruption of vital cell function leading to cell death. This review will discuss the potential properties of essential oils and heavy metal ions, in particular tea tree oil and silver ions as alternative antimicrobial agents for the treatment of wounds. Page 1 of 52 International Wound Journal Abstract The increasing occurrence of hospital acquired infections and the emerging problems posed by antibiotic resistant microbial strains have both contributed to the escalating cost of treatment. -

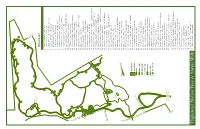

Highstead Native T Ree & Shrub W

25 26 23 22 24 27 18 21 19 20 29 28 17 30 31 16 34 33 15 14 laurel 32 collection 13 12 Plant List 35 1 Quercus palustris pin oak 2 Salix discolor pussy willow 3 Rhus typhina staghorn sumac (female) 36 4 Populus deltoides cottonwood 5 Betula populifolia gray birch 38 37 6 Prunus serotina black cherry 7 Populus tremuloides quaking aspen 39 8 Populus grandidentata large-toothed aspen 40 9 Aronia melanocarpa black chokeberry 41 10 Juniperus virginiana red cedar 11 Vaccinium angustifolium lowbush blueberry 10 12 Vaccinium stamineum deerberry 11 9 13 Kalmia latifolia mountain laurel 8 14 Ostrya virginiana American hop hornbeam 68 15 Kalmia angustifolia sheep laurel 69 16 Amelanchier canadensis shadbush 7 42 17 Hamamelis virginiana common witch hazel 18 Quercus rubra red oak 5 6 67 19 Fagus grandifolia American beech 4 66 20 Betula alleghaniensis yellow birch 70 3 43 65 2 barn 21 Viburnum lentago nannyberry 64 1 22 Fraxinus americana white ash 63 62 59 57 44 23 Vaccinium vitis-idaea var. minus mountain cranberry 61 58 60 46 24 Gaultheria procumbens creeping wintergreen 25 Castanea dentata American chestnut 50 47 48 45 26 Rhododendron prinophyllum roseshell azalea 51 49 27 Rhododendron periclymenoides pinxterbloom azalea 28 Quercus velutina black oak 29 Viburnum acerifolium maple-leaved viburnum 54 52 30 Liriodendron tulipifera tulip tree 56 55 53 31 Vaccinium corymbosum highbush blueberry 32 Quercus prinus chestnut oak 33 Betula lenta sweet birch pond 34 Quercus coccinea scarlet oak 35 Gaylussacia baccata black huckleberry 36 Acer rubrum red -

Oysters, Red Chilli & Lime Dressing 4.5Ea Betel Leaf, Smoked Trout, Galangal, Roe 8.5Ea Fried Tumeric & Garlic Marina

Oysters, red chilli & lime dressing 4.5ea Betel leaf, smoked trout, galangal, roe 8.5ea Fried tumeric & garlic marinated Barramundi fish wings, chilli, lime 9.5ea Minced chicken & prawns, pineapple, mandarin, fried shallots, peanuts 14.5 Silken tofu pork dumplings, sweet chilli sauce 14.5 Mr Jones son-in-law eggs, sweet tamarind sauce 14.5 Pumpkin eggnet, caramelized coconut, peanuts, lime, lemongrass 16.5 Chiang Mai larp minced duck, northern herbs, betel leaf 18.5 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Spicy green papaya salad, coconut rice – mild, hot, Thai hot! 21 Salad of pomelo, ginger, toasted coconut, peanuts, lime, palm sugar caramel 16.5 Thai vegetable & herb salad, sweet & sour sesame dressing 19.5 Stir fried Chinese watercress, garlic, yellow bean 14.5 Stir fried mussels, chilli, lime, peanuts 18.5 Stir fried pork belly, Chinese broccoli, garlic, oyster sauce 26 Stir fried wagyu beef, charred onions, Thai basil, oyster sauce 36 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Caramelized pork, chilli vinegar, star anise 18.5 Chicken broth, shiitake, young coconut, Thai basil 9.5 Thai fried chicken, house made sriracha sauce & plum sauce 26 Whole fish market price fried with a salad of pomelo, chilli, lime, mint Or steamed, young ginger, spring onions, soy Yellow curry of cauliflower, tomato, cucumber relish 24 Penang curry of chicken, peanuts, Thai -

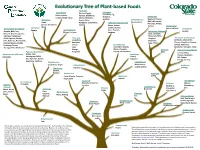

Evolutionary Tree of Plant-Based Foods

Evolutionary Tree of Plant-based Foods Rosaceae Sapindaceae Almond, Apple, Moraceae Breadfruit, Fig, Ackee, Lychee, Apricot, Blackberry, Mulberry, Solanaceae Longan, Maple Syrup Cherry, Nectarine, Jackfruit Eggplant, Peppers Malvaceae Peach, Plum, Convolvulaceae (bell, chili, sweet, Cacao Raspberry, Strawberry, Sweet potato Fabaceae (Leguminosae) Pimento), Potato, (Cocoa, Chocolate) Quince Beans, Jicama, Tomato Verbenaceae Okra Lentils, Licorice, Brassicaceae (Cruciferae) Caricaceae Lemon verbena Pedaliaceae Papaya Anacardiaceae Peas, Peanuts, Lamiaceae (Labiatae) Sesame Arugula, Bok Choy, Mango, Cashews Soybean Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, Basil, Lavender, Cabbage, Cauliflower, Marjoram, Mint, Collard greens, Daikon, Rutaceae Oregano, Asteraceae (Compositae) Kale, Kohlrabi, Horseradish, Grapefruit, Rosemary, Artichoke, Chamomile, Mustard greens, Radish, Kumquat, Sage, Thyme Chicory, Dandelion, Endive, Rutabaga, Turnip, Lemon, Cucurbitaceae Lettuce, Radicchio, Turnip greens, Watercress Lime Cucumber, Gourds, Sunflower, Tarragon, Yakon Orange, Melon, Pumpkin, Oleaceae Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) Tangerine Squash, Watermelon Poaceae (Gramineae) Olive Carrot, Celery, Barley, Corn, Asparagaceae (Liliaceae) Betulaceae Chervil, Coriander, Lemongrass, Millet, Asparagus Filbert, Dill, Fennel, Oat, Rye, Rice, Wheat, Hazelnut Parsley, Parsnip Sugarcane, Sorghum Zingiberaceae Juglandaceae Black walnut, Cardamom, Ginger Euphorbiaceae Araliaceae English walnut Muscaceae Cassava Ginseng Banana, Plantain Annonaceae Rubiaceae Custard Apple, Pawpaw, Myrtaceae -

Show Activity

A Emollient *Unless otherwise noted all references are to Duke, James A. 1992. Handbook of phytochemical constituents of GRAS herbs and other economic plants. Boca Raton, FL. CRC Press. Plant # Chemicals Total PPM Abelmoschus moschatus Ambrette; Muskmallow; Musk Okra; Tropical Jewel Hibiscus 1 300000.0 Abelmoschus esculentus Okra 1 178400.0 Achillea moschata Iva 1 Aconitum napellus Monkshood; Soldier's Cap; European Aconite; Garden Monkshood; Queen's Fettle; Helmet Flower; Aconite; 1 500000.0 Bear's-Foot; Turk's Cap; Friar's Cap; Garden Wolfsbane; Blue Rocket Acorus calamus Calamus; Flagroot; Sweet Calamus; Sweetroot; Myrtle Flag; Sweetflag 1 Actaea racemosa Black Cohosh; Black Snakeroot 1 Aegle marmelos Bael fruit; Bael de India 1 Aesculus hippocastanum Horse Chestnut 1 1200000.0 Aframomum melegueta Alligator Pepper; Melegueta Pepper; Malagettapfeffer (Ger.); Grains-of-Paradise; Malagueta (Sp.); Guinea 1 Grains Alliaria petiolata Garlic Mustard 1 Allium sativum var. sativum Garlic 1 Alocasia macrorrhiza Giant Taro 1 1447800.0 Aloe vera Bitter Aloes; Aloe 1 Alpinia officinarum Chinese Ginger; Lesser Galangal 1 500000.0 Alpinia galanga Siamese Ginger; Greater Galangal; Languas 1 Althaea officinalis White Mallow; Marshmallow 2 750000.0 Amorphophallus campanulatus Elephant-Foot Yam 1 1495494.0 Ananas comosus Pineapple 1 38.0 Andira inermis Cabbage Bark 1 Anethum graveolens Garden Dill; Dill 1 Angelica sinensis Dong Gui; Dang Qui; Dang Quai; Chinese Angelica; Dang Gui; Dong Quai 1 Annona squamosa Sweetsop; Sugar-Apple 1 Annona muricata Soursop