Czech-Armenians Relations: a Brief Historical Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Form Within a Form a Conversation Between Dor Guez and the Composer Hagop K

A Form within a Form A Conversation between Dor Guez and the Composer Hagop K. Dor Guez: The fate, or should I say the physical presence, of a work of art that isn't fixed to a place doesn't necessarily attests to its origin, or sources of influence. This is especially true in the case of musical works like your own. Hagop K.: Similarly to movables such as ceramics, carpets, silverware, manuscripts, etc., sometimes it's impossible to point with any certainty to the origin of a melody. Objects such as these are easily transferable and thus it's often hard to pinpoint the identity of their maker. This enabled nationalistic historians to bend their findings and dub unmistakablely Armenian artifacts "Ottoman." D.G.: The nation-state's artificial borders distort the historiography of art. For this reason, the phenomenon of inscription (in Armenian "hishatakaran") is not accidental when we are dealing with minority culture, which is often nomadic. H.K.: More than any other people, we insist on artistic validation and authorship. There is a built-in blindness in the writing on Christian artisanship originating from Armenia. For example, academic literature tends to ignore the Armenian influence on the ceramics made throughout the Ottoman Empire. The prevalent reasons given to this oversight are that many of the objects manufactured by Armenian potters were commissioned by Muslim clients, or that Armenian carpets were woven and commissioned by Muslim subjects of the Empire. Having been subsumed by the metanarrative under the heading "Ottoman" or "Turkish" works, ornaments manufactured in Armenian workshops (decorated ceramic tiles, jars and eggs) were deemed unworthy of a chapter of their own. -

Armenian Christians in Jerusalem: 1700 Years of Peaceful Presence*

Laury Haytayan1 Прегледни рад Arab Region Parliamentarians Against Corruption UDK:27(479.25)(569.44) ARMENIAN CHRISTIANS IN JERUSALEM: 1700 YEARS OF PEACEFUL PRESENCE* Abstract This paper examines the presence of the Armenians in Jerusalem for the past 1700 years. This historical account sheds the light on the importance of Jerusa- lem for the Armenians, especially for the Armenian Church that was granted the authority to safeguard the Holy Places in the Holy Land with the Greek and Latin Churches. During the centuries, the Armenians survived all the conquests and were able to find all sorts of compromises with all the different powers that conquered Jerusalem. This study shows that the permanent presence is due to the wise religious authorities and the entire Armenian community who had no backing from super powers but they had their religious beliefs and their per- sistence in safeguarding the Holy Places of Christianity. The author takes the reader back in History by stopping at important events that shaped the history of the Armenians in the Holy Land. Key words: Jerusalem, Armenians, Crusaders, Holy Land, St James Monas- tery, Old City, Armenian Quarter. Introduction This paper comes at a time when Christians in Iraq and Egypt are being mas- sacred in their churches, Christians in Nazareth are being forbidden to decorate a Christmas tree in public space, and Christians in Lebanon are seeking to pre- serve their political rights to safeguard their presence in their Homeland. At a time, when the Palestinian Authority is alerting the International Community of the danger of the continuous and ferocious settlement construction in East Jerusalem by the State of Israel, and at a time when Christians of the East are being silent on the fate of Jerusalem by leaving it in the hands of the Palestinian and Israeli negotiators, hoping that the Unites States will be the caretaker of the Christians of Jerusalem. -

GENS VLACHORUM in HISTORIA SERBORUMQUE SLAVORUM (Vlachs in the History of the Serbs and Slavs)

ПЕТАР Б. БОГУНОВИЋ УДК 94(497.11) Нови Сад Оригиналан научни рад Република Србија Примљен: 21.01.2018 Одобрен: 23.02.2018 Страна: 577-600 GENS VLACHORUM IN HISTORIA SERBORUMQUE SLAVORUM (Vlachs in the History of the Serbs and Slavs) Part 1 Summary: This article deals with the issue of the term Vlach, that is, its genesis, dis- persion through history and geographical distribution. Also, the article tries to throw a little more light on this notion, through a multidisciplinary view on the part of the population that has been named Vlachs in the past or present. The goal is to create an image of what they really are, and what they have never been, through a specific chronological historical overview of data related to the Vlachs. Thus, it allows the reader to understand, through the facts presented here, the misconceptions that are related to this term in the historiographic literature. Key words: Vlachs, Morlachs, Serbs, Slavs, Wallachia, Moldavia, Romanian Orthodox Church The terms »Vlach«1, or later, »Morlach«2, does not represent the nationality, that is, they have never represented it throughout the history, because both of this terms exclusively refer to the members of Serbian nation, in the Serbian ethnic area. –––––––––––– [email protected] 1 Serbian (Cyrillic script): влах. »Now in answer to all these frivolous assertions, it is sufficient to observe, that our Morlacchi are called Vlassi, that is, noble or potent, for the same reason that the body of the nation is called Slavi, which means glorious; that the word Vlah has nothing -

Princely Suburb, Armenian Quarter Or Christian Ghetto? the Urban Setting of New Julfa in the Safavid Capital of Isfahan (1605-1722)

Ina Baghdiantz-MacCabe* Princely Suburb, Armenian Quarter or Christian Ghetto? The Urban Setting of New Julfa in the Safavid Capital of Isfahan (1605-1722) Résumé. Faubourg princier, quartier arménien ou ghetto chrétien ? L’établissement urbain de New Joulfa dans la capitale safavide d’Ispahan (1605-1722). L’article examine les lieux d’habitation des Arméniens à Isfahan et dans le nouveau bourg de la Nouvelle Joulfa, un quartier résidentiel construit spécialement pour recevoir les marchands de soie de Joulfa déportés à Isfahan en 1604 par Abbas Ier (r.1587-1629). Ce quartier se trouve, non sans raison politique, face aux résidences des notables, souvent eux mêmes originaires du Caucase pendant ce règne, dans la nouvelle capitale d’Isfahan. Il est démontré que, contrairement aux villes arabes sous domination ottomane étudiées par André Raymond, comme Alep ou Le Caire, il n’existait pas un quartier arménien. À leur arrivée, seuls les marchands prospères s’étaient vus accorder le droit de séjour dans le bourg de la Nouvelle Joulfa, tandis que les artisans et les domestiques habitaient parmi la population musulmane d’Isfahan même. La Nouvelle Joulfa était strictement réservée aux Joulfains. Aux termes d’un décret, les musulmans, les missionnaires catholiques et les autres arméniens, n’étaient autorisés à y résider. Cette situation changerait vers le milieu du XVIIe siècle. Après 1655, ce qui était un bourg “princier” – car le prévôt des marchands de Joulfa provient, selon les sources, d’une famille considérée princière –, deviendrait un “quartier arménien”, les Arméniens d’ Isfahan, après avoir été chassés de la capitale, ayant été transférés vers le bourg. -

University of California

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Calouste Gulbenkian Library, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 1925-1990: An Historical Portrait of a Monastic and Lay Community Intellectual Resource Center Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8f39k3ht Author Manoogian, Sylva Natalie Publication Date 2012 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8f39k3ht#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Calouste Gulbenkian Library, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 1925-1990: An Historical Portrait of a Monastic and Lay Community Intellectual Resource Center A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science by Sylva Natalie Manoogian 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Calouste Gulbenkian Library, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 1925-1990: An Historical Portrait of a Monastic and Lay Community Intellectual Resource Center by Sylva Natalie Manoogian Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science University of California, Los Angeles 2013 Professor Mary Niles Maack, Chair The Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem is a major religious, educational, cultural, and ecumenical institution, established more than fourteen centuries ago. The Calouste Gulbenkian Library is one of the Patriarchate’s five intellectual resource centers. Plans for its establishment began in 1925 as a tribute to Patriarch Yeghishe I Tourian to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood. Its primary mission has been to collect and preserve valuable works of Armenian religion, language, art, literature, and history, as well as representative works of world literature in a number of languages. -

1 the Armenian Dialects of Jerusalem Bert Vaux, Harvard University in Armenians in the Holy Land, Michael Stone, Ed. Louvain

The Armenian Dialects of Jerusalem Bert Vaux, Harvard University In Armenians in the Holy Land, Michael Stone, ed. Louvain: Peeters, 2002. 1. Introduction The Armenian community in Jerusalem was first established somewhere between the third and fifth centuries, and since that time has remained relatively isolated from the rest of the Armenian-speaking world. It has furthermore been subjected to a degree of Arabic influence that is quite uncommon among Armenian linguistic communities. For these reasons, it is not surprising that a distinctive dialect of Armenian has emerged in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem. Strangely, though, this dialect has never been studied by Armenologists or linguists, and is not generally known outside of the Armenian community in Israel. (Mention of the Armenian dialect of Jerusalem is notably absent in the standard works on Armenian dialectology and in the Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia, for example.) Those who do know about the distinctive speech of the Jerusalem Armenians generally consider it to be “bad Armenian” supplemented by words A thousand thanks to Vartan Abdo, Arpine, †Antranig Bakirjian, Chris Davis, Yeghia Dikranian, Hagop Hachikian, Garo Hagopian, Vartuhi Hokeyan, Tavit Kaplanian, Arshag Merguerian, Madeleine Habosian Derderian, Shushan Teager, Abraham Terian, Rose Varzhabedian, Aram Khachadurian, and Apkar Zakarian for all of the hours they devoted to assisting me with this project. The transcription employed here is that of REArm; linguists should note the following oddities of this system: <¬> represents a voiced uvular fricative, IPA [“]. <x> represents a voiceless uvular fricative, IPA [X]. <j> represents a voiced alveopalatal affricate, IPA [dz]. <c> represents a voiceless alveopalatal affricate, IPA [ts]. -

Genocide Descending: Half-Jews in Poland and Half-Armenians in Turkey

GENOCIDE DESCENDING: HALF-JEWS IN POLAND AND HALF-ARMENIANS IN TURKEY Serafi m Seppälä All the consequences of Armenian genocide and Jewish Shoah are still not fully realised or comprehended. In addition to the systematic annihilation of populations and cultures, the fates of the survivors continue to be a tragic reverberation of the genocidal events. In both cases, most of the survivors escaped to other countries and later became subjects and objects of a number of biographies and studies. However, not every survivor fl ed. In both Serafi m Seppälä is a professor of systematic theology genocides, there were also a remarkable number of victimised individuals who survived the in the University of Eastern Finland. His main scholarly massacres through negligence of the murderers, or by being taken to families, and continued to live in the country of the atrocities, changing or hiding their religious and cultural identity interests are in early Syriac and Greek patristic literature, or becoming victims of forced change of identity. especially Mariology and spirituality, in addition to the The existence of these peoples in Poland and Turkey remained a curious unrecognized idea of Jerusalem in the three monotheistic religions. subject that extremely little was known of until recently. In this article, the present situation Several of his Finnish publications deal with the rabbinic of both of these groups is discussed in comparative terms in order to outline the character literature and Judaism. Seppälä has also published a of their identity problems. The comparison is all the more interesting due to the fact that cultural history of Armenia and two monographs on the obvious differences between the two social contexts underline the signifi cance of the Armenian Genocide in Finnish language, concentrating on common factors in the post-genocidal experience. -

Rural Political Culture and Resistance in Postwar Czechoslovakia

SVĚTLANA: RURAL POLITICAL CULTURE AND RESISTANCE IN POSTWAR CZECHOSLOVAKIA Mira Markham A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Chad Bryant Karen Auerbach Donald J. Raleigh © 2019 Mira Markham ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Mira Markham: Světlana: Rural Political Culture and Resistance in Postwar Czechoslovakia (under the direction of Chad Bryant) This thesis examines the role of the wartime partisan movement in shaping anti- Communist resistance in Moravian Wallachia, a rural region in the easternmost corner of the Bohemian lands. The experience of partisan war in this region, as well as the prominence of former partisans in postwar public life, led to the development of a distinctive local political culture opposed to the bureaucratic power of the central state. Local grievances drove former partisans in Moravian Wallachia to mobilize networks and practices of resistance developed during wartime to challenge the consolidating Communist regime. Police agents also drew on partisan practices to reconstitute local opposition and resistance into a prosecutable conspiratorial network that could be understood within the framework of official ideology. Through the case of Světlana, a resistance network that emerged among former partisans in 1948, this paper situates both opposition and repression within a specific local context, demonstrating the complex interactions between state and society in the Czechoslovak countryside and providing a new perspective on the issue of anti-Communist resistance in Czechoslovakia during the Stalinist era. -

The Spatial Distribution of Gambling and Its Economic Benefits to Municipalities in the Czech Republic

MORAVIAN GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS 2017, 25(2):2017, 104–117 25(2) Vol. 23/2015 No. 4 MORAVIAN MORAVIAN GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS Institute of Geonics, The Czech Academy of Sciences journal homepage: http://www.geonika.cz/mgr.html Figures 8, 9: New small terrace houses in Wieliczka town, the Kraków metropolitan area (Photo: S. Kurek) doi: 10.1515/mgr-2017-0010 Illustrations to the paper by S. Kurek et al. The spatial distribution of gambling and its economic benefits to municipalities in the Czech Republic David FIEDOR a *, Zdeněk SZCZYRBA b, Miloslav ŠERÝ b, Irena SMOLOVÁ b, Václav TOUŠEK b Abstract Gambling is a specific type of economic activity that significantly affects many aspects of society. It is associated mainly with negative impacts on the lives of individuals and their families, but it also has a positive economic impact on the public budgets of states, regions and municipalities. In this article, we focus on a geographic assessment of the development of gambling in the Czech Republic, which is based on a spatial analysis of data on licensed games and data on the revenues of municipalities arising from gambling. It turns out that the occurrence of gambling is strongly influenced by binary centre/periphery dichotomy, with the exception of the Czech-Austrian and Czech-German border areas which are characterised by a high concentration of casinos resulting from more rigid regulation of gambling on the other side of the border. In this research, the authors develop an innovative scientific discipline within Czech human geography: The geography of gambling. Keywords: gambling, regulation, municipalities, spatial patterns, economic benefits, Czech Republic Article history: Received 1 August 2016; Accepted 12 May 2017; Published 30 June 2017 1. -

To Believe Or Not to Believe the Crop Circle Phenomenon in the Netherlands Õ.Ì

To believe or not to believe The crop circle phenomenon in The Netherlands õ.ì Th eo Meder är iE ËiE In ¡hc Summe¡ of 2001, I srarted my rcserrch find ley lines rvith their clowsing rods or rneas- of n¿r¡atives colrcerning crop circles ancl their ure the energy with cheir pendulums, some possibly supenutural, clivine, ecologic,rl or come to meditate. l'atmers are sclclom pleased extraterrescrial origin. I wâ[ted to focus ol-r with clop circlcs because of the h¡rves¡ loss rh( râlcs Jnd c,rnrcptions ìrt u lrich clop cir- involved - c¿usecl not only by thc fìattening cles ale interpretcd ¡s non-rr¡n-macle signs of of the crop, but also by the trampling of curi- <(9 the time"^. Furthermore, rny ¡escr¡ch involved ous visito¡s. Sceptic scientists hardly bother to oq the concemporary cult movement ¡hat sc¿r¡tccl con-re, buc csoteric ¡ese¡rchers come to rnves- 9+{ with ufos in ¡he 1950s as a kincl of'proto- tigate, measure, sample, film and photograph, New ;\ge rnovernent'. 1 Crop circles u'e thc for later analysis rnd interpretation. Journalìsts 5i most tangible element of this mode¡n New r isir ¡he lormltion" cìuring rhc silly scrsc'n in Agc convicrion, which eìso incorporatcs ufo sealch of a juicy stor¡ preferably on the mys- sightings, alien rbductions, cattle mutilation, tery of the unexplaincd, on the subject of licde govcrûment cover-ups, free energy, lcy Iines, grecn mqn. or un thË l¡ct thct thc cntire cr,'p mysterious orbs of light, alte¡native ¡heories on circle phenonenon is a huge man-macle ¡rracci ¡hc c¡e¿tion of man, conneccior-rs with ancient cal jokc.2 ancl prehistoric Íronuments (like tÌre Ììgyptian pymnids ¿nd Cel¡ic Stonehcngc), thc cosmìc Englancl: where the knowledge of lost civilizations (Adar.rtis, ìVlayas phenomenon stârted a likc othe¡- etc.), and the expectations of rhe coming of Although some people to believe I new crâ or cven ¡n Encl of l)ays. -

Odzemok: Cultural and Historical Development

81 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 16, No. 2/2016 MATÚŠ IVAN Odzemok: Cultural and Historical Development Odzemok: Cultural and Historical Development MATÚŠ IVAN Department of Ethnology and World Studies, University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava [email protected] ABSTRACT This article characterizes the male dance odzemok as one of the most representative dances in the broad spectrum of Slovak folk dances. A more detailed analysis and subsequent analysis of the literature confirms the absence of a comprehensive integrated material concerning odzemok in a wider context. This text further highlights the historical development of said male dance in the central geographic area, and analyzes the factors that led to the development of its present form. KEY WORDS: folk dance, folk music, male dance, odzemok, hajduch, valachian colonization Introduction Odzemok has an important place in the history of dance culture in Slovakia. It belongs along with young men's or lad's dances and verbunk to a group of men´s dances. The consequences of its origin, its development and forms are not clearly defined even now. DOI: 10.1515/eas-2017-0006 © University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. All rights reserved. 82 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 16, No. 2/2016 MATÚŠ IVAN Odzemok: Cultural and Historical Development If we want to study dance and be more familiar with it, we cannot focus only on its form and content but we must take into concern a wider context. Dance, as well as other folk forms, exists only at the moment of its concrete active realisation. Preserving the dance is correlative with the active expression of a different kind of dance, which helps us to spread it from generation to generation. -

Ani Kolangian

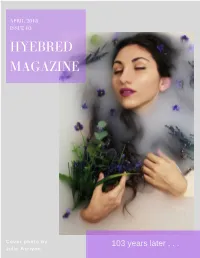

APRIL 2018 ISSUE 03 HYEBRED MAGAZINE Cover photo by 103 years later . Julie Asriyan Forget-Me-Not Issue 03 Prose Music Anaïs Chagankerian . 6 Brenna Sahatjian . 13 Lizzie Vartanian Collier . 20 Ani Kalayjian . 34 Armen Bacon . .38 Mary Kouyoumdjian . 36 Poetry Art & Photography Ani Chivchyan . 3 Julie Asriyan . 10 Ronald Dzerigian . 14 Ani Iskandaryan . 18 Nora Boghossian . .16 Susan Kricorian . 28 Rita Tanya . .31 Ani Kolangian . .32 John Danho . .49 Nicole Burmeister . .52 A NOTE OF GRATITUDE Dear Faithful Reader, This issue is dedicated to our Armenian ancestors. May their stories never cease to be told or forgotten. As April is Genocide Awareness Month, the theme for this issue is fittingly 'Forget-Me-Not.' It has been 103 years since the Armenian Genocide, a time in Armenian history that still hurts and haunts. HyeBred Magazine represents the vitality and success of the Armenian people; it showcases how far we have come. Thank you to our wonderfully talented contributors. Your enthusiastic collaboration enhances each successive publication. Thank you, faithful reader, as your support is what keeps this magazine alive and well. Շնորհակալություն. The HyeBred Team Ani Chi vchyan Self Love don't let yourself get in the way of yourself the same way you can harm yourself, adding salt to those wounds and grow only in sorrow and grief only to become tired of yourself you have the power to heal and love admire celebrate your existence in this world water those roots and make something beautiful out of you H Y E B R E D I S S U E 0 3 | 3 By