In Shakespeare's Twelfth Night

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher Resource Pack I, Malvolio

TEACHER RESOURCE PACK I, MALVOLIO WRITTEN & PERFORMED BY TIM CROUCH RESOURCES WRITTEN BY TIM CROUCH unicorntheatre.com timcrouchtheatre.co.uk I, MALVOLIO TEACHER RESOURCES INTRODUCTION Introduction by Tim Crouch I played the part of Malvolio in a production of Twelfth Night many years ago. Even though the audience laughed, for me, it didn’t feel like a comedy. He is a desperately unhappy man – a fortune spent on therapy would only scratch the surface of his troubles. He can’t smile, he can’t express his feelings; he is angry and repressed and deluded and intolerant, driven by hate and a warped sense of self-importance. His psychiatric problems seem curiously modern. Freud would have had a field day with him. So this troubled man is placed in a comedy of love and mistaken identity. Of course, his role in Twelfth Night would have meant something very different to an Elizabethan audience, but this is now – and his meaning has become complicated by our modern understanding of mental illness and madness. On stage in Twelfth Night, I found the audience’s laughter difficult to take. Malvolio suffers the thing we most dread – to be ridiculed when he is at his most vulnerable. He has no resolution, no happy ending, no sense of justice. His last words are about revenge and then he is gone. This, then, felt like the perfect place to start with his story. My play begins where Shakespeare’s play ends. We see Malvolio how he is at the end of Twelfth Night and, in the course of I, Malvolio, he repairs himself to the state we might have seen him in at the beginning. -

Twelfth Night

SAMPLE – INCOMPLETE SCRIPT a Community Shakespeare Company edition of Twelfth Night original verse adaptation by Richard Carter 1731 Center Road Lopez Island, WA 98261 360.468.3516 [email protected] Enriching young lives, cultivating community” NOTES ABOUT PRODUCTION The author asks that anyone planning to stage one of his adaptations please contact him for permission, via the CSC website: www.communityshakespeare.org . There are no performance royalties due. He asks that scripts be purchased for every member of a cast. Frequently asked questions include, “What if my group is mostly girls?” Cross-casting (females playing male roles) is almost inevitable; once it is explained that males played all the female roles in Shakespeare’s time, this obstacle is easily overcome. Moreover, girls see that many of the “big” parts are male, so those wanting more stage time gravitate toward male roles. The author also encourages groups to take certain liberties, such as changing the sex of some roles. With little alteration of the text, a duke may become a duchess, an uncle may become an aunt. In answer to the question, “What if I have too many (or too few) students?” some parts may be divided amongst several actors (a messenger becomes two messengers), or actors may take on more than one role. In short, do what is necessary to make the play fun and accessible for young people; the author did! Synopsis of the play Orsino, Duke of Illyria, is in love with Olivia, a proud and beautiful countess. She spurns his suit, being in mourning for her late father and brother. -

The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume2, Number 1, February 2018 Pp. 97-105 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no1.7 The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night Rachid MEHDI Department of English, Faculty of Art Abderahmane-Mira University of Bejaia, Algeria Abstract This article is a study on the representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night; or, What You Will, one of his most popular comic play in the modern theatre. In mocking Malvolio’s morality and ridiculous behaviour, Shakespeare wanted to denounce Puritans’ sober society in early modern England. Indeed, Puritans were depicted in the play as being selfish, idiot, hypocrite, and killjoy. In the same way, many other writers of different generations, obviously influenced by Shakespeare, have espoused his views and consequently contributed to promote this anti-Puritan literature, which is still felt today. This article discusses whether Shakespeare’s portrayal of Puritans was accurate or not. To do so, the writer first attempts to define the term “Puritan,” as the latter is quite equivocal, then take some Puritans’ characteristics, namely hypocrisy and killjoy, as provided in the play, and analyze them in the light of the studies of some historians and scholars, experts on the post Reformation Puritanism, to demonstrate that Shakespeare’s view on Puritanism is completely caricatural. Keywords: caricature, early modern theatre, Malvolio, Puritans, satire Cite as: MEHDI, R. (2018). The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies, 2 (1). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no1.7 Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies 97 eISSN: 2550-1542 |www.awej-tls.org AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies Volume, 2 Number 1, February 2018 The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night MEHDI Introduction Puritans had been the target of many English writers during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. -

Reimagining Shakespeare in the Young Adult Contemporary

REIMAGINING SHAKESPEARE IN THE YOUNG ADULT CONTEMPORARY NOVEL by Jodi Lyn Turchin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2017 Copyright by Jodi Lyn Turchin 2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to her committee members for all of their guidance and support, and special thanks to my advisor for being with me every step of the way during the writing of this manuscript. iv ABSTRACT Author: Jodi Lyn Turchin Title: Reimaginging Shakespeare in the Young Adult Contemporary Novel Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Emily Stockard Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2017 This research focuses on how Young Adult (YA) novelists adapt Shakespeare’s plays to address the concerns of a contemporary teenage audience. Through the qualitative method of content analysis, I examined adaptations of the three most commonly read texts in the high school curriculum: Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and Hamlet. The research looked for various patterns in the adaptations and analyzed the choices made by the authors in aligning their texts to or deviating from the original plays. A final chapter addresses practical classroom application in using adaptations to teach the plays to high school students. v REIMAGINING SHAKESPEARE IN THE YOUNG ADULT CONTEMPORARY NOVEL INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

Book Review: Celia R. Daileader. <Em>Racism, Misogyny, and the Othello Myth</Em>

Book Reviews 149 Notes 1 Augustine Curio, A Notable Historie of the Saracens, trans. Thomas Newton (London, 1575), sigs C3v-C4r. 2 Public Record Office, London. State Papers 12/275/94. 3 See the examples in Matthew Dimmock, New Turkes: Dramatizing Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005). 4 Robert Wilson, A right excellent and famous Comedy called the three Ladies of Lon- don ... (London, 1584), sig. F1v. Celia R. Daileader. Racism, Misogyny, and the Othello Myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Pp x, 256. Celia R. Daileader’s lively and provocative discussion of Othello and inter- racial sexuality begins with her concept of ‘Othellophilia’: ‘the critical and cultural fixation in Shakespeare’s tragedy of inter-racial marriage to the exclu- sion of broader definitions, and more positive visions, of inter-racial eroti- cism’ (6). Why, she wonders, did the pattern of a sexual relationship between a black man and a white woman (as opposed to a black woman and a white man) come to be such a prevalent literary trope? Antony and Cleopatra is also a great Shakespearean tragedy featuring inter-racial sexuality—assuming one believes that the dramatist’s Cleopatra was meant to be black—but it has never achieved the universal appeal of Othello. Daileader finds the answer in the imbrication of racism with misogyny. Mutually reinforcing constructs, racism and misogyny work hand in hand to demonize not just black sexuality but female sexuality as well. Ever since the early modern period, which begins Daileader’s survey, the culture of white patriarchy, frightened of female sexual autonomy, has elided that fear with a horror of miscegenation. -

Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo

PARODY, POPULAR CULTURE, AND THE NARRATIVE OF JAVIER TOMEO by MARK W. PLEISS B.A., Simpson College, 2007 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish and Portuguese 2015 This thesis entitled: Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo written by Mark W. Pleiss has been approved for the Department of Spanish and Portuguese __________________________________________________ Dr. Nina L. Molinaro __________________________________________________ Dr. Juan Herrero-Senés __________________________________________________ Dr. Tania Martuscelli __________________________________________________ Dr. Andrés Prieto __________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Buffington Date __________________________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and We find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the abovementioned discipline. iii Pleiss, Mark W. (Ph.D. Spanish Literature, Department of Spanish and Portuguese) Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo Dissertation Director: Professor Nina L. Molinaro My thesis sketches a constellation of parodic Works Within the contemporary Spanish author Javier Tomeo's (1932-2013) immense literary universe. These novels include El discutido testamento de Gastón de Puyparlier (1990), Preparativos de viaje (1996), La noche del lobo (2006), Constructores de monstruos (2013), El cazador de leones (1987), and Los amantes de silicona (2008). It is my contention that the Aragonese author repeatedly incorporates and reconfigures the conventions of genres and sub-genres of popular literature and film in order to critique the proliferation of mass culture in Spain during his career as a writer. -

The Aesthetics of Railing: Troilus and Cressida and Coriolanus

The Aesthetics of Railing:Troilus and Cressida and Coriolanus Maria Teresa Micaela Prendergast The College of Wooster Cet essai explore comment Shakespeare utilise la rhétorique des insultes cruelles et for- tement métaphoriques des débuts de la modernité afin de réaliser une rivalité agressive entre le déclinant idéal aristocratique élisabéthain du sang et du langage épique d’une part, et le théâtre satirique en émergence d’autre part. Ce type de théâtre se justifie en associant le guerrier aristocratique à un corps suintant, efféminé, et malade. Cet essai se concentre en particulier sur les pièces Troilus and Cressida et Coriolanus, qui éta- blissent un fort lien entre la manifestation de maladies internes sur la peau et la perte d’autonomie masculine. Dans Troilus and Cressida, Thersites, incarnant le personnage du fou, domine la pièce avec ses discours vicieux qui transforment sur le plan rhétorique le personnage héroïque de l’aristocrate masculin en une créature abjecte. Parallèlement, Coriolan, en fort contraste avec Thersites, est un guerrier autonome, qui néanmoins sou- tient l’opinion de Thersites que le spectacle théâtral, ainsi que la fréquentation des gens du peuple dégradent les idéaux guerriers aristocratiques. Les deux pièces suggèrent que c’est à travers une langue caustique et scatologique de l’insulte, de pair avec une destruction rhétorique des idéaux de l’aristocratie guerrière, que le théâtre britannique du début du dix-septième siècle remplace une esthétique traditionnelle de l’élite faite de sang héroïque par une célébration de la puissance rhétorique des croûtes et des éruptions cutanées. ike many of his Elizabethan and Jacobean contemporaries, Shakespeare was Lcaught up in the art of railing. -

James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, and Robyn Warhol, Series Editors

THEORY AND INTERPRETATION OF NARRATIVE James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, and Robyn Warhol, Series Editors Narrative Theory Core Concepts and Critical Debates DAVID HERMAN JAMES PHELAN PETER J. RABINOWITZ BRIAN RICHARDSON ROBYN WARHOL THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Narrative theory : core concepts and critical debates / David Herman ... [et al.]. p. cm. — (Theory and interpretation of narrative) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-5184-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-5184-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-1186-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1186-0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0-8142-9285-3 (cd-rom) 1. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Herman, David, 1962– II. Series: Theory and interpretation of nar- rative series. PN212.N379 2012 808.036—dc23 2011049224 Cover design by James Baumann Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Part One Perspectives: Rhetorical, Feminist, Mind-Oriented, Antimimetic 1. Introduction: The Approaches Narrative as Rhetoric JAMES PHElan and PETER J. Rabinowitz 3 A Feminist Approach to Narrative RobYN Warhol 9 Exploring the Nexus of Narrative and Mind DAVID HErman 14 Antimimetic, Unnatural, and Postmodern Narrative Theory Brian Richardson 20 2. Authors, Narrators, Narration JAMES PHElan and PETER J. -

Gulling of Malvolio in Twelfth Night

Subject-English Hons. Core Course Semester II Paper -ENGH-H-CC-T-4 Teacher’s name-Nilanjana Chakraborty Gulling of Malvolio in Twelfth Night: Malvolio is the steward of Olivia’s household. He dislikes all manner of fun and festivity and for that reason he reproaches Sir Toby for making late night gathering. Maria calls him a kind of ‘Puritan’. His puritanism and aversion to fun misplace him in the jolly society of the Illyrians. He responds to revelry and humour of the household with indignation. His duty is to maintain order in the household. As Olivia is not really in mourning, she enjoys Feste’s disorderly playfulness. But Malvolio’s reaction to this disorder is ‘distempered’. He finds nothing but offence in Feste’s remarks. Malvolio is sick of self-love and Olivia says this right on his face, “O, you are sick of self-love, Malvolio, and taste with a distempered appetite.” Actually, he is suffering from the exaggerated sense of self-importance. He also lacks a sense of humour. Malvolio dislikes parties, drinking, merriment of all sorts, and so he is very critical about the conduct of Sir Toby and others who are always involved in frivolities. Sir Toby, Maria, Feste and Sir Andrew Aguecheek openly resent Malvolio and Maria calls him an “affectioned ass” who uses high-flown language without necessarily knowing its proper meaning. He is not resented only as a Puritan, but also for the fact that he aspires to marry Olivia. Before he sees the letter, he is indulging his ambitious and substantial day-dreams; they include not only marrying Olivia and thereby becoming Count Malvolio, but also, from that position reproving Sir Toby. -

Twelfth Night KEY CHARACTERS and SENSORY MOMENTS

Twelfth Night KEY CHARACTERS AND SENSORY MOMENTS Characters Viola Sebastian Olivia Malvolio Sir Andrew Sir Toby Feste Maria Orsino Antonio Sensory Moments Below is a chronological summary of the key sensory moments in each act and scene. Latex balloons are used onstage throughout the show. Visual, dialogue or sound cues indicating dramatic changes in light, noise or movement are in bold. PRESHOW • A preshow announcement plays over the loudspeaker and instruments tune onstage. ACT ONE SCENE ONE SENSORY MOMENTS • Feste begins to sing a song. When he puts DESCRIPTION a paper ship in the water, the storm begins. At Duke Orsino’s palace in Illyria, Cesario and There is frequent loud thunder, flickering others sing for Orsino. He’s in love with the lights and flashes of lightning via strobe countess Olivia, but it’s unrequited because she lights. Actors shout during the turmoil, is in mourning for her brother and won’t receive cymbals crash and drums rumble. his messengers. • The storm sequence lasts about 90 seconds. • After the storm, lights slowly illuminate SENSORY MOMENTS the stage. • Actors begin singing a song. Orsino enters the stage and picks up a balloon. When he walks to the center of the stage, the balloon SCENE TWO pops loudly. • When Orsino says, “Love-thoughts lie rich DESCRIPTION when canopied with bowers,” the actors Viola washes ashore in Illyria, saved by the leave the stage, suspenseful music plays and ship’s captain. She asks the captain to help her the lights go dark. disguise herself so she can get work in Orsino’s court. -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

View a PDF of the Program with Actor Bios

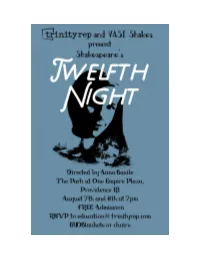

Cast List VIOLA, later disguised as CESARIO – Katherine Berryhill CAPTAIN – Sylvia Sammon-Burns DUKE ORSINO, duke of Illyria – Noah Saltzman CURIO, his attendant – E. Grace Viveiros (Understudy) OLIVIA, a wealthy countess – Elizabeth Larabee MARIA, Olivia’s gentlewoman – Ursula Talbot MALVOLIO, her steward – Jonathan Baran SIR TOBY BELCH, Olivia’s uncle – Mack Meaders SIR ANDREW AGUECHEEK, friend of Sir Toby – Jalil Neal CLOWN, a jester in Olivia’s house – Noah Saltzman PRIEST – E. Grace Viveiros (Understudy) SEBASTIAN, Viola’s twin brother – Sylvia Sammon-Burns ANTONIO, sea captain and friend to Sebastian – Ursula Talbot OFFICER – E. Grace Viveiros (Understudy) Production Team Director – Anna Basile Assistant Director & Administrative Intern – E. Grace Viveiros Director of Education & Accessibility – Jordan Butterfield Associate Education Director – Matthew Tibbs School Partnerships & Professional Development Manager – Natalie Dreyer Costume Pieces – Amanda Downing-Carney Poster Design by – Lindsey Jenkins Special Thanks Rhode Island Department of Education, Berkeley Investments, City of Providence Art, Culture + Tourism, URI Child Development Center, Marianne Apice, Kaii Almeida, Shawn Williams, Amanda Downing Carney, buses, family, friends, and you for joining us! Jonathan Baran (Malvolio) is appearing in his first Shakespeare play, but is no stranger to the stage. He played Bill in Mamma Mia at LaSalle Academy and Santa Claus in Elf Jr. at Stadium Theatre. He also starred as private eye Warren G. Smugeye in the world premiere play, The Whale in the Hudson through YASI Players. Jonathan loves baguettes. Noah Saltzman (Duke Orsino/Clown) has been at YASI for seven years. He appeared on the Trinity Rep mainstage as Fleance in Macbeth and was Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream through YASI Shakes.