An Interview with Jim Shaw’ 13 February 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Tightbeam

11 TIGHTBEAM Up until now Bujold has kept the relationship concerning Aral, Cordelia, and Oliver on the “down-low” even from readers. I checked with other reviewers and found I was not alone in not realizing that they were even lovers let alone involved in a ménage a trois. Some of the re- ally fanatic fans of the series have been going back to the older books to see if the author really foreshadowed this development or has just thrown it into the story arc now after thirty years, but I wasn’t planning on doing it myself. May the Schwartz Be With You ...Review by Tom McGovern A few issues ago, I reviewed The MLJ Companion, which is a de- tailed history of the Archie Comics superheroes. More recently, I’ve been reading The Silver Age Sci-Fi Companion by Mike W. Barr, which is also an interesting book, though not as impressive or absorb- ing as the MLJ work. There are a few differences between the two works. MLJ is in full color throughout, whereas Silver Age Sci-Fi is all in B&W, except for the covers. The MLJ book is also about twice as thick, and consists of historical articles, interviews and anecdotes, with a small amount of the content consisting of actual listings of issues, artists, writers, dates, etc. Silver Age Sci-Fi, on the other hand, consists mostly of listings that are much more detailed than those in MLJ, along with a few articles and interviews thrown in. That’s not necessarily a bad thing; it’s just a dif- ferent approach. -

Zatanna and the House of Secrets Graphic Novels for Kids & Teens 741.5 Dc’S New Youth Movement Spring 2020 - No

MEANWHILE ZATANNA AND THE HOUSE OF SECRETS GRAPHIC NOVELS FOR KIDS & TEENS 741.5 DC’S NEW YOUTH MOVEMENT SPRING 2020 - NO. 40 PLUS...KIRBY AND KURTZMAN Moa Romanova Romanova Caspar Wijngaard’s Mary Saf- ro’s Ben Pass- more’s Pass- more David Lapham Masters Rick Marron Burchett Greg Rucka. Pat Morisi Morisi Kieron Gillen The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of satirical than the romantic visions of DC Comics is in peril. Again. The ever- Williamson and Wood. Harvey’s sci-fi struggling publisher has put its eggs in so stories often centered on an ordinary many baskets, from Grant Morrison to the shmoe caught up in extraordinary circum- “New 52” to the recent attempts to get hip with stances, from the titular tale of a science Brian Michael Bendis, there’s hardly a one left nerd and his musclehead brother to “The uncracked. The first time DC tried to hitch its Man Who Raced Time” to William of “The wagon to someone else’s star was the early Dimension Translator” (below). Other 1970s. Jack “the King” Kirby was largely re- tales involved arrogant know-it-alls who sponsible for the success of hated rival Marvel. learn they ain’t so smart after all. The star He was lured to join DC with promises of great- of “Television Terror”, the vicious despot er freedom and authority. Kirby was tired of in “The Radioactive Child” and the title being treated like a hired hand. He wanted to character of “Atom Bomb Thief” (right)— be the idea man, the boss who would come up with characters and concepts, then pass them all pay the price for their hubris. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Vol. 72, Ed. 10 | the West Georgian Editorial Generation Generalization Jaenaeva Watson on the Role of Breaking the Odds and Start a Pasta Business?” Their Talents

The West GeorgianEst. 1934 Volume 72, Edition Ten November 13 - November 19, 2017 In this DINING WITH MARVEL VS DC HOOP UP Who rules the box UWG ready for edition... WOLVES UWG students office? basketball season learn table / / PAGE 4 / / PAGE 7 etiquitte / / PAGE 2 A Star is Leaving UWG Photo Courtesy of Dr. Bob Powell Photo Courtesy of Dr. Photo Credit: Steven Broome Jamie Walloch his students’ names. interacting with the physics majors as In 2005, Powell became chair of the well as others that I taught in science Contributing Writer Physics and Astronomy department instead courses, compared to today’s students who of retiring. presumably are better prepared. I am not Even a health problem in 2014 did so sure that our current students work quite Dr. Bob Powell is retiring from UWG after not stop the dedicated professor from doing as hard and really remember and can apply 50 years of dedication to serving students what he loves. He continued teaching after things that they should have learned in within his teachings of physics and recovery and decided to retire after exactly earlier courses, however.” astronomy along with serving as director of 50 years and one semester of teaching. In Fall 1971, Powell became a the Observatory and a faculty advisor. “The obvious time for me to retire faculty advisor for the Chi Omega Sorority. A In September of 1967, Powell began was May of last year but I like the fall member of the sorority and a student in his teaching at West Georgia College at 26 semester,” said Powell. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

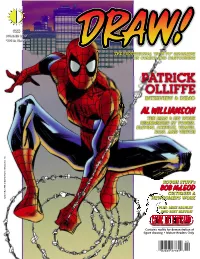

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Dec. 2012 $10.95

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

T Cartoonists

Publisher of the Worl d’sG r eatest Car toon ists SUMMER 2019 SUMMER 2019 7563 lake city way ne • seattle, wa 98115 • usa telephone: 206-524-1967 • fax: 206-524-2104 customer service: 800-657-1100 [email protected] • www.fantagraphics.com Distributed to the book trade in the In Japan: In Singapore, Malaysia: Distributed to the comic book special- United States by: ty market by Diamond Comics Distrib- Rockbook – Gilles Fauveau Pansing Distribution Pte Ltd utors (www.diamondcomics.com). W.W. NORTON AND COMPANY, INC. Expirime 5F 10-10 Ichibancho 1 New Industrial Road 500 Fifth Avenue Chiyoda-ku Times Centre For information on distribution New York, NY 10110 102-0082 Tokyo Singapore 536196 elsewhere, please contact Martin Tel.: 212-354-5500 Japan Tel (65) 6319 9939 Bland. Fax: 212-869-0856 Tel: (81) 90 9700 2481 Fax (65) 6459 4930 Order Dept. Tel.: 800-233-4830 Tel: (81) 90 3962 4650 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Order Dept. Fax: 800-458-6515 General Inquiries email: [email protected] Customer Service Dept.: 800-233-4830 In Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, [email protected] Special Sales Dept.: Myanmar: Sales & Distribution Martin Bland 800-286-4044 In Taiwan and Korea: [email protected] www.wwnorton.com Hardy Bigfoss International Co., Ltd. Publicity & Marketing Jacq Cohen B. K. Norton Ltd. 293 Maenam Kwai Road, Tambol Tha [email protected] In the United Kingdom & Europe: 5F, 60 Roosevelt Road Makham Print Buyer Jason Miles Sec. 4, Taipei 100 Amphur Muang [email protected] -

The Comic Book and the Korean War

ADVANCINGIN ANOTHERDIRECTION The Comic Book and the Korean War "JUNE,1950! THE INCENDIARY SPARK OF WAR IS- GLOWING IN KOREA! AGAIN AS BEFORE, MEN ARE HUNTING MEN.. .BIAXlNG EACH OTHER TO BITS . COMMITTING WHOLESALE MURDER! THIS, THEN, IS A STORY OF MAN'S INHUMANITY TO MAN! THIS IS A WAR STORY!" th the January-February 1951 issue of E-C Comic's Two- wFisted Tales, the comic book, as it had for WWII five years earlier, followed the United States into the war in Korea. Soon other comic book lines joined E-C in presenting aspects of the new war in Korea. Comic books remain an underutilized popular culture resource in the study of war and yet they provide a very rich part of the tapestry of war and cultural representation. The Korean War comics are also important for their location in the history of the comic book industry. After WWII, the comic industry expanded rapidly, and by the late 1940s comic books entered a boom period with more adults reading comics than ever before. The period between 1935 and 1955 has been characterized as the "Golden Age" of the comic book with over 650 comic book titles appearing monthly during the peak years of popularity in 1953 and 1954 (Nye 239-40). By the late forties, many comics directed the focus away from a primary audience of juveniles and young adolescents to address volatile adult issues in the postwar years, including juvenile delinquency, changing family dynamics, and human sexuality. The emphasis shifted during this period from super heroes like "Superman" to so-called realistic comics that included a great deal of gore, violence, and more "adult" situations. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

TwoMorrows 2015 Catalog SAVE 15 ALL BOOKS, MAGS WHEN YOU% & DVDs ARE 15% OFF ORDER EVERY DAY AT ONLINE! www.twomorrows.com *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. Four Ways To Order: • Save us processing costs by ordering Print or Digital Editions ONLINE at www.twomorrows.com and you get at least 15% OFF cover price, plus exact weight-based postage (the more you order, the more you save on shipping—especially overseas customers)! Plus you’ll get a FREE PDF DIGITAL EDITION of each PRINT item you order, where available. OR: • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL DIGITALEDITIONS and add $1 per magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US for Media Mail shipping. AVAILABLE OUTSIDE THE US, PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! OR: • Download our new Apps on the Apple and Android App Stores! OR: • Use the Diamond Order Code to order at your local comic book shop! CONTENTS DIGITAL ONLY BOOKS . 2 AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES . .3 MODERN MASTERS SERIES . 4-5 COMPANION BOOKS . 6-7 ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES . 8-9 COMICS & POP CULTURE BOOKS . 10 ROUGH STUFF & WRITE NOW . 11 DRAW! MAGAZINE . 12 HOW-TO BOOKS . 13 COMIC BOOK CREATOR MAGAZINE . 14 COMIC BOOK ARTIST MAGAZINE . 15 JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR . 16-19 ALTER EGO MAGAZINE . 20-27 BACK ISSUE! MAGAZINE . 28-32 To be notified of exclusive sales, limited editions, and new releases, sign up for our mailing list! All characters TM & ©2015 their respective owners. -

Wynonna Earp's Evenhuis Covers Overstreet

March 5, 2020 For Immediate Release Wynonna Earp’s Evenhuis Covers Overstreet #50 First Time for Wynonna on the Cover of the Guide Hunt Valley, Maryland – Beau Smith’s Wynonna Earp, the demon hunter, descendant of famous lawman Wyatt Earp, and star of both her own graphic novels from IDW Publishing and SyFy’s TV series, is the first western character to be featured on the cover of The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, which this year celebrates its 50th anniversary. Regular Wynonna Earp artist Chris Evenhuis also makes his Overstreet debut with this edition of The Bible of serious comic book collectors, dealers, and historians. This cover will be offered in the April 2020 PREVIEWS from Diamond Comic Distributors in both soft cover ($29.95 SRP) and hardcover ($37.50) editions. The Wynonna Earp cover will be exclusively available in comic book shops (and from the Gemstone website for those who don’t live near a comic shop). “Chris Evenhuis is more than an artist, he’s an animator of life. His Overstreet cover is living proof of that,” said Beau Smith, creator and writer of Wynonna Earp. “With the 50th edition of The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, I hope not only collectors, but readers, creators and lovers of pop culture will truly understand what a textbook of information and history the Guide is. The history that was created in print, remains in print for all to learn from for all ages past, present and future.” “Capturing not only Wynonna Earp herself, but a number of her supporting players, Chris Evenhuis really poured himself into this cover.