What's Cooking in Special Collections Terry Warth University of Kentucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burgoo Saddler Taylor University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Staff ubP lications McKissick Museum 2007 Burgoo Saddler Taylor University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/mks_staffpub Part of the History Commons Publication Info Published in New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture - Foodways (Volume 7), ed. John T. Edge, 2007, pages 132-133. http://www.uncpress.unc.edu/browse/book_detail?title_id=1192 © 2007 by University of North Carolina Press Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. This Article is brought to you by the McKissick Museum at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. sian of munon is the major difference between burgoo and Brunswick stew. Otherwise, the nyo stews are quite similar, in both preparation and con sumption. While western Kentucky burgoo recipes are distinguished by this critical difference, many of them actually in clude other meats as wel l. Some recipes call for squirrel, veal, oxtail, or pork, bringing to mind jokes told by stew masters that refer to «possum or animals that got too close to the paLM Ihe story telling and banter during the long hours of stew preparation are keys to strong social bonds that develop over a period of time. Kentuckians tell stories about the legendary Gus Jaubert, a member of Morgan's Raiders during the Civil War, who supposedly prepared hundreds of gallons of the spicy hunter's stew for the general's men. -

October 2010.Pub

Issue # 33 October 2010 Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY EDWARDSVILLE The Secret Ingredient: Recipes INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Topic Introduction 2 Connecting to Illinois 3 Close to Home 3 Learn More with 4 American Memory In The Classroom 6 Test Your Knowledge 8 Image Sources 9 CONTACTS • Melissa Carr [email protected] Editor • Cindy Rich [email protected] • Amy Wilkinson [email protected] eiu.edu/~eiutps/newsletter Page 2 Recipes Secret Ingredient Welcome to the Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Although Simmons borrowed many of the recipes from Sources Newsletter a collaborative project of Teaching British cookbooks, she added her own twist by including with Primary Sources Programs at Eastern Illinois ingredients native to America such as corn meal. University and Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Recipes can be much more than ingredients and Our goal is to bring you topics that connect to the Illinois measurements, they are a primary source offering a Learning Standards as well as provide you will amazing glimpse into a family’s history. You may have a recipe, items from the Library of Congress. Recipes are tattered from being folded and unfolded again and again mentioned specifically within ISBE materials for the over generations. Aside from creating a delicious dish, following Illinois Learning Standards (found within goal, this recipe can show a family’s identity through culture, standard, benchmark or performance descriptors), 3- tradition or religious significance. Ingredients may have Write to communicate for a variety of purposes. 6- been added or changed over Demonstrate and apply a knowledge and sense of the years depending on the Recipes can be much numbers, including numeration and operations (addition, items available in the subtractions, multiplication, more than ingredients region. -

10000 General Knowledge Questions and Answers 10000 General Knowledge Questions and Answers No Questions Quiz 1 Answers

10000 quiz questions and answers www.cartiaz.ro 10000 general knowledge questions and answers 10000 general knowledge questions and answers www.cartiaz.ro No Questions Quiz 1 Answers 1 Carl and the Passions changed band name to what Beach Boys 2 How many rings on the Olympic flag Five 3 What colour is vermilion a shade of Red 4 King Zog ruled which country Albania 5 What colour is Spock's blood Green 6 Where in your body is your patella Knee ( it's the kneecap ) 7 Where can you find London bridge today USA ( Arizona ) 8 What spirit is mixed with ginger beer in a Moscow mule Vodka 9 Who was the first man in space Yuri Gagarin 10 What would you do with a Yashmak Wear it - it's an Arab veil 11 Who betrayed Jesus to the Romans Judas Escariot 12 Which animal lays eggs Duck billed platypus 13 On television what was Flipper Dolphin 14 Who's band was The Quarrymen John Lenon 15 Which was the most successful Grand National horse Red Rum 16 Who starred as the Six Million Dollar Man Lee Majors 17 In the song Waltzing Matilda - What is a Jumbuck Sheep 18 Who was Dan Dare's greatest enemy in the Eagle Mekon 19 What is Dick Grayson better known as Robin (Batman and Robin) 20 What was given on the fourth day of Christmas Calling birds 21 What was Skippy ( on TV ) The bush kangaroo 22 What does a funambulist do Tightrope walker 23 What is the name of Dennis the Menace's dog Gnasher 24 What are bactrians and dromedaries Camels (one hump or two) 25 Who played The Fugitive David Jason 26 Who was the King of Swing Benny Goodman 27 Who was the first man to -

The Kentucky Barbecue Book Wes Berry Western Kentucky University

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® English Faculty Book Gallery English 3-2013 The Kentucky Barbecue Book Wes Berry Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/english_book Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Berry, Wes, "The Kentucky Barbecue Book" (2013). English Faculty Book Gallery. Book 14. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/english_book/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Book Gallery by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction I am large, I contain multitudes of barbecue. —Walt Whitman, speaking in a western Kentucky drawl, overheard in a vision I had on May 27, 2012, while strolling near the confl uence of the Green and Barren rivers. ’ve recently been diagnosed with Hyper Enthusiastic Barbecue Disorder I(HEBD). I’m supposed to drink eight ounces of KC Masterpiece daily to make the cravings go away. Th e prescription isn’t working very well. I still get the nervous trembles when I think about deliciously smoked meats. But I do know this: I’m not fond of KC Masterpiece and many other major-brand sauces—thick concoctions sweetened with corn syrup and sometimes tainted by unnatural-tasting liquid smoke. My students sometimes tell me that their lives are so busy it’s diffi cult for them to turn in work on time. Th ey ask for extended deadlines. I say, “You think you’ve got it bad? I got HEBD. I can’t even concentrate on what you’re saying to me right now. -

Dine-In Or Carryout 270-422-2727

Dine-In or Carryout 10% Surcharge on carry outs 270-422-2727 634 By-Pass Rd Brandenburg, KY 40108 (In the River Ridge Plaza) Tuesday - Thursday 11am to 8pm Friday & Saturday 11am to 9pm Sunday 11am to 8pm www.docsbbqsmokeshack.com Honeywings or Hotwings Hot, Honey, or BBQ Served with Celery Sticks 7ct $9.99 10ct $12.99 Doc’s Naked Smoked Wings Doc’s Naked Smoked Wings 7ct $9.99 10ct $12.99 Jalapeno Poppers *Extra Dressing/Sauce $.75* (Cheddar Cheese or Cream Cheese filled) Dressings: Blue Cheese, Buttermilk Ranch, Lite 7ct $6.99 10ct $9.99 Ranch, Honey Mustard, BBQ Sauce, Thousand Island, French, Honey French, Golden Italian Cheese Fries Garden of Eatin With Pulled Pork $8.99 Leaf Eaters (House Salad) $4.99 With Brisket $9.99 Without Pulled Pork or Brisket $4.99 Meat Eaters $8.99 Fried Pickles Bacon, Cheddar Cheese, Tomatoes, and Eggs. Piled high with your choice of Grilled Chicken, With Zesty Sauce $6.99 Fried Chicken, Brisket or Pulled Pork. Onion Rings Burgoo and Cornbread With Zesty Sauce $7.99 Okra, Corn, Potatoes, Green Beans, Brisket, Pulled Pork and Smoked Chicken $9.99 Doc’s Smokin Egg Roll 4 Full Size Pork or Brisket $9.99 Fried Mushrooms With Zesty Sauce $7.99 Burgoo Consumer Advisory: Consuming raw or uncooked meats (Beef, Poultry, Seafood, Shellfish, or Eggs) may increase risk of food-borne illness. choice of 1 side Hot Link Sandwich $7.99 1/2lb Applewood Smoked Bacon Cheeseburger Chicken Breast 1/2lb Hamburger Grilled or Fried $9.99 Lettuce, Tomato, Onions, Pickles, Mayo Smoked Sausage Add Cheese - $1.00 Sandwich Add Bacon -

Americans Celebrate with Food, Whether New Year's Eve, the 4Th Of

Corn-Pork-Beef-Wheat Evening Presentation Iowa State University Ames, Iowa Americans celebrate with food, whether New Year’s eve, the 4th of July, Thanksgiving, or a host of local or regional, secular and religious festivities. American food has evolved and diversified through the centuries, from the simple, sustaining dishes of Colonial times to the complex food combinations that characterize the new millennium. Behind each food lies a history of use at different times at different geographical regions of America. Today, my objective is to briefly explore four of these foods: corn and pork; beef and wheat. And I begin with corn. Some call it maize, others call it corn. Regardless of name it is the same food, Zea mais. The word maize comes from the Taino language, spoken by the Arawaks, a Caribbean Native American nation, who greeted Columbus in 1492. The word maize subsequently transferred to Spanish, and entered other European languages as well. The alternative word, corn, originally spelled corne, is an Old English generic term for grain, whose meaning subsequently shifted to designate wheat. American-style English, however, continues to use the word corn in the sense of maize, usage that has continued into the 21st century. Maize was domesticated and first cultivated in the central valley of Mexico, perhaps 6,000 years ago, and ultimately became the primary dietary staple throughout Mesoamerica. Cultural exchange and trade gradually brought maize and other Mesoamerican crops northward into the geographical region now defined by the United States, where the grain was adopted in the semi- arid lands of the American southwest about 1,000 years ago, and about 800 years ago in the eastern seaboard region of North America. -

Kentucky Back Road Restaurant Recipes Cookbook (Sample)

Kentucky Back Road Restaurant Recipes Cookbook (Sample) Do you find that the hardest part of cooking for your family is coming up with what to cook? Great American Cookbooks can help make that so simple with easy-to-follow, delicious-tasting recipes from hometown cooks across the USA. Our goal is to provide everyday recipes for the everyday cook. That is why we strive to select the best recipes using ingredients most cooks already have in their kitchen. Just to give you an idea of the great cookbooks Great American has to offer, here is a small sample of Kentucky Back Road Restaurant Recipes Cookbook. Each book we produce is a full-color, top- quality cookbook with 200 to 300 wonderful family recipes. We also include interesting stories and articles that will bring you and your family hours of fun. Thank you for taking the time to view this Great American Cookbook Sample. A Cookbook & Restaurant Guide AnI¦a Musgrove Great American Publishers www.GreatAmericanPublishers.com TOLL-FREE 1-888-854-5954 Recipe Collection © 2014 by Great American Publishers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Great American Publishers 501 Avalon Way Suite B • Brandon, MS 39047 toll-free 1-888-854-5954 • www.GreatAmericanPublishers.com ISBN 978-1-934817-17-9 by Anita Musgrove Layout and design by Cyndi Clark 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 Printed in the United States of America All images are copyrighted by the creator noted through thinkstock/istock/ (unless otherwise indicated). -

Historic American Building Survey

US 421 MILTON-MADISON BRIDGE (KY-NBI NO.: 112B00001N) HAER KY-53 (US 421 Madison-Milton Bridge (IN-NBI No.: 32005)) HAER KY-53 (Indiana State Highway Bridge #421-39-6003) US 421 spanning the Ohio River between Milton, KY & Madison, IN Milton Trimble County Kentucky PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD MIDWEST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 601 Riverfront Drive Omaha, NE 68102 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD U.S. 421 MILTON-MADISON BRIDGE (KY-NBI No. 112B00001N) HAER NO. KY-53 Location: Spanning the Ohio River via U.S. 421, between Milton, Trimble County, Kentucky (KY), and Madison, Jefferson County, Indiana (IN) UTM: Zone 16 Northing 641694 Easting 4287948 QUAD: Madison East, KY 1973, revised 1978 Date of Construction: 1929 Engineer: J. G. White Engineering Corporation, New York, New York Builder: Mount Vernon Bridge Company, Mount Vernon, Ohio and Vang Construction, Maryland Present Owner: Kentucky Transportation Cabinet and Indiana Department of Transportation Present Use: Vehicular bridge connecting Milton, Trimble County, Kentucky (KY) to Madison, Jefferson County, Indiana (IN) via U.S. 421 Significance: The U.S. 421 Milton-Madison Bridge is considered eligible by both the Kentucky State Historic Preservation Officer (KY SHPO) and the Indiana State Historic Preservation Officer (IN SHPO) for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion C for its type and design and also under Criterion A for its association with early twentieth century truss bridge construction practices. U.S. 421 MILTON-MADISON BRIDGE HAER No. KY-53 Page 2 Project Information: The U.S. -

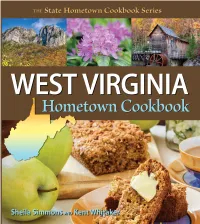

West Virginia Hometown Cookbook (Sample)

West Virginia Hometown Cookbook (Sample) Do you find that the hardest part of cooking for your family is coming up with what to cook? Great American Cookbooks can help make that so simple with easy-to-follow, delicious-tasting recipes from hometown cooks across the USA. Our goal is to provide everyday recipes for the everyday cook. That is why we strive to select the best recipes using ingredients most cooks already have in their kitchen. Just to give you an idea of the great cookbooks Great American has to offer, here is a small sample of West Virginia Hometown Cookbook. Each book we produce is a full-color, top- quality cookbook with 200 to 300 wonderful family recipes. We also include interesting stories and articles that will bring you and your family hours of fun. Thank you for taking the time to view this Great American Cookbook Sample. Maryland Heights Overlook Harpers Ferry National Park Dolly Sods Wilderness Monongahela National Forest WEST VIRGINIA Hometown Cookbook BY SHEILA SIMMONS AND KENT WHITAKER GREAT AMERICAN PUBLISHERS WWW.GREATAMERICANPUBLISHERS.COM TOLL-FREE 1.888.854.5954 Recipe Collection © 2015 by Great American Publishers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Great American Publishers 171 Lone Pine Church Road • Lena, MS 39094 toll-free 1.888.854.5954 • www.GreatAmericanPublishers.com ISBN 978-1-934817-20-9 First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 by Sheila Simmons & Kent Whitaker Designed by Roger & Sheila Simmons Front cover photos: ?? Back cover -

Mark's Dinner Menu

MARK’S DINNER MENU MARK’S RIB DINNERS MARK’S COMBO RIB PLATTER .........................15.99 RIB DINNERS A 6-bone serving APPETIZERS PORK, BRISKET, HONEYWINGS™ AND ™ RIB DINNER ..........................19.99 #1 MARK’S FAMOUS HONEYWINGS A 10-bone serving BABY BACK RIBS .........17.49 Order of 7 ........................................................10.50 FULL SLAB DINNER .......... 23.99 Order of 10 ...................................................... 13.00 #2 BABY BACK RIBS AND A 12/14-bone serving CHICKEN BREAST .......19.49 ONION STRAWS 4-BONE RIB BASKET ........10.25 BABY BACK RIBS, 1/2 Basket ............................................................6.25 A 4-bone serving with spicy fries #3 BAR-B-Q PORK AND Full Basket ...........................................................7.25 Add a side salad............................3.25 CHICKEN BREAST .....19.49 BIRD-IN-A-NEST™ 7 Honeywings™ on a nest of onion straws ....12.50 GF Rib Dinners and Rib Combo Dinner #2 and #3 are gluten-free when served without toast SWEET CORNBREAD All Mark’s Rib and Rib Combo Dinners are served with your choice of Basket of 6 muffins ...........................................4.50 2 side items (on back) and country toast. Excludes Rib Basket. FRIED PICKLES A customer favorite ...........................................7.25 MARK’S DINNER ENTRÉES MARK’S BURGOO A hearty stew with meat, veggies and spices PORK, CHICKEN OR TURKEY BAR-B-Q DINNER ...........13.49 Cup .......................................................................3.99 BRISKET BAR-B-Q -

Chicken of the Trees | Food & Drink Feature | Chicago Reader

Newsletters Follow us Mobile Log in / Create Account Search chicagoreader.com GO FBOEOSTD O&F D CRHINICKA |G FOOOD T&H ED RPEINOKP FLE AISTSUURE STRAIGHT DOPE SAVAGE LOVE AGENDA EVENTS LOCATAIuOguNstS 16, 2IS01S2UES ARTICLE ARCHIVES GAMES Like 1.7K Tweet 43 REPRINTS Share Chicken of the trees The rural eastern gray squirrel has long been a valued food source, but what about its urban cousin? By Mike Sula @MikeSula PETER THOMAS RYAN Winner of the MFK Fisher Distinguished Writing Award from the James Beard Foundation. t starts every summer with the first ripening tomato. Maybe it's I the early blush on a squat Cherokee Purple, or the lighter stripes of a Green Zebra turning pale yellow, or a lime Bush Beefsteak going gradually olive, then pink, then red. The effects of the sun on this single fruit carry the promise of summer, and the subtle message of whether it will be a good season for tomatoes, or even whether it will be a good summer overall. I watch the weather forecasts and gently squeeze with my fingertips to calculate the precise day I'll pluck it. But without fail—sometimes the very day before I plan for this auspicious moment—I'm foiled. I'll climb to the roof to find the fruit's smooth surface violated, chiseled and gnawed by a honed set of incisors. The marauder is insolent and indiscriminate. Sometimes the fruit is discarded, half eaten, on the roof. Other times it remains hanging on the vine. Now this tomato becomes a sign of war. -

Geology Department Newsletter

Geology Department N e w s l e t t e r Western Illinois University Department News 2009-2010 Happy 2010! The Department of Geology is once again happy to have the chance to share some of the happenings of the past year with our alumni and friends. As you’ll notice when reading this newsletter, we have had another busy, successful year here in Macomb. Luckily, all of the budget problems in the state of Illinois haven’t caused us to change our activities yet. Speaking of budgets, we are proud to announce that you, our alumni, donate at a higher dollar amount per capita than any of the departments in the College of Arts and Sciences! Our small but active department rarely beats those departments with hundreds of majors (e.g. Biological Sciences, English and Journalism, Psy- chology) at anything so Dr. Calengas was suitably proud of our alumni when these figures were shared at a College meeting. We do have a couple new faces in the Geology Department this year. To offset the loss in enroll- ment caused by offering a small-enrollment Freshman section of our Introduction to the Earth course (Geol 110), the College agreed to hire an instructor to teach an additional section of Geol 110 each semester. The instructor we hired, Sara Bennett, was already quite familiar with the de- partment since she came to Macomb with me in 1994. Our other new member of the Department is our secretary Diane Edwards. Diane joined us mid-year and has immediately fit right in.