Synthetic Cannabinoids in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Selective Reversible FAAH Inhibitor, SSR411298, Restores The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The selective reversible FAAH inhibitor, SSR411298, restores the development of maladaptive Received: 22 September 2017 Accepted: 26 January 2018 behaviors to acute and chronic Published: xx xx xxxx stress in rodents Guy Griebel1, Jeanne Stemmelin2, Mati Lopez-Grancha3, Valérie Fauchey3, Franck Slowinski4, Philippe Pichat5, Gihad Dargazanli4, Ahmed Abouabdellah4, Caroline Cohen6 & Olivier E. Bergis7 Enhancing endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) signaling has been considered as a potential strategy for the treatment of stress-related conditions. Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) represents the primary degradation enzyme of the eCB anandamide (AEA), oleoylethanolamide (OEA) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA). This study describes a potent reversible FAAH inhibitor, SSR411298. The drug acts as a selective inhibitor of FAAH, which potently increases hippocampal levels of AEA, OEA and PEA in mice. Despite elevating eCB levels, SSR411298 did not mimic the interoceptive state or produce the behavioral side-efects (memory defcit and motor impairment) evoked by direct-acting cannabinoids. When SSR411298 was tested in models of anxiety, it only exerted clear anxiolytic-like efects under highly aversive conditions following exposure to a traumatic event, such as in the mouse defense test battery and social defeat procedure. Results from experiments in models of depression showed that SSR411298 produced robust antidepressant-like activity in the rat forced-swimming test and in the mouse chronic mild stress model, restoring notably the development of inadequate coping responses to chronic stress. This preclinical profle positions SSR411298 as a promising drug candidate to treat diseases such as post-traumatic stress disorder, which involves the development of maladaptive behaviors. Te endocannabinoid (eCB) system is formed by two G protein-coupled receptors, CB1 and CB2, and their main transmitters, N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide; AEA) and 2-arachidonoyglycerol (2-AG)1. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Drug Alcohol Depend

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Drug Alcohol Depend. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014 October 1; 143: 251–256. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.004. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor allosteric modulator ORG 27569 on reinstatement of cocaine- and methamphetamine- seeking behavior in rats* Li Jinga,b, Yanyan Qiua, Yanan Zhangc, and Jun-Xu Lia aDepartment of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, USA bDepartment of Physiology and Pathophysiology, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, China cResearch Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA Abstract Background—Cannabinoid CB1 receptors play an essential role in drug addiction. Given the side effect profiles of orthosteric CB1 antagonism, new strategies have been attempted to modulate this target, such as CB1 receptor allosteric modulation. However, the effect of CB1 allosteric modulation in drug addiction is unknown. The present study examined the effects of the CB1 receptor allosteric modulator ORG27569 on the reinstatement of cocaine- and methamphetamine- seeking behavior in rats. Methods—Rats were trained to self-administer 0.75 mg/kg cocaine or 0.05 mg/kg methamphetamine in 2-hr daily sessions for 14 days which was followed by 7 days of extinction sessions in which rats responded on the levers with no programmed consequences. On reinstatement test sessions, rats were administered ORG27569 (1.0, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg, i.p.) or SR141716A (3.2 mg/kg, i.p.) 10 min prior to re-exposure to cocaine- or methamphetamine-paired cues or a priming injection of cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) or methamphetamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.). -

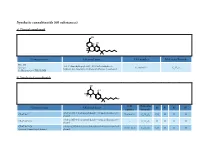

Synthetic Cannabinoids (60 Substances) A) Classical Cannabinoid

Synthetic cannabinoids (60 substances) a) Classical cannabinoid OH H OH H O Common name Chemical name CAS number Molecular Formula HU-210 3-(1,1’-dimethylheptyl)-6aR,7,10,10aR-tetrahydro-1- Synonym: 112830-95-2 C H O hydroxy-6,6-dimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-9-methanol 25 38 3 11-Hydroxy-Δ-8-THC-DMH b) Nonclassical cannabinoids OH OH R2 R3 R4 R1 CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1 R2 R3 R4 number Formula rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methyloctan- 2- yl) CP-47,497 70434-82-1 C H O CH H H H phenol 21 34 2 3 rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methylheptan- 2- yl) CP-47,497-C6 - C H O H H H H phenol 20 32 2 CP-47,497-C8 rel-2- [(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methylnonan- 2- yl) 70434-92-3 C H O C H H H H Synonym: Cannabicyclohexanol phenol 22 36 2 2 5 CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1 R2 R3 R4 number Formula rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methyldecan- 2- yl) CP-47,497-C9 - C H O C H H H H phenol 23 38 2 3 7 rel-2- ((1 R,2 R,5 R)-5- hydroxy- 2- (3- hydroxypropyl)cyclohexyl)- 3-hydroxy CP-55,940 83003-12-7 C H O CH H H 5-(2- methyloctan- 2- yl)phenol 24 40 3 3 propyl rel-2- [(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxy-5,5-dimethylcyclohexyl]- 5- (2- Dimethyl CP-47,497-C8 - C H O C H CH CH H methylnonan-2- yl)phenol 24 40 2 2 5 3 3 c) Aminoalkylindoles i) Naphthoylindoles 1' R R3' R2' O N CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1’ R2’ R3’ number Formula [1-[(1- methyl- 2- piperidinyl)methyl]- 1 H-indol- 3- yl]- 1- 1-methyl-2- AM-1220 137642-54-7 C H N O H H naphthalenyl-methanone 26 26 2 piperidinyl -

Grunddokument 2

The cellular processing of the endocannabinoid anandamide and its pharmacological manipulation Lina Thors Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Neuroscience SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden Umeå 2009 1 Copyright©Lina Thors ISBN: 978-91-7264-732-9 ISSN: 0346-6612 Printed by: Print & Media Umeå, Sweden 2009 2 Abstract Anandamide (arachidonoyl ethanolamide, AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) exert most of their actions by binding to cannabinoid receptors. The effects of the endocannabinoids are short-lived due to rapid cellular accumulation and metabolism, for AEA, primarily by the enzymes fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH). This has led to the hypothesis that by inhibition of the cellular processing of AEA, beneficial effects in conditions such as pain and inflammation can be enhanced. The overall aim of the present thesis has been to examine the mechanisms involved in the cellular processing of AEA and how they can be influenced pharmacologically by both synthetic natural compounds. Liposomes, artificial membranes, were used in paper I to study the membrane retention of AEA. The AEA retention mimicked the early properties of AEA accumulation, such as temperature- dependency and saturability. In paper II, FAAH was blocked by a selective inhibitor, URB597, and reduced the accumulation of AEA into RBL2H3 basophilic leukaemia cells by approximately half. Treating intact cells with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein, an isoflavone found in soy plants and known to disrupt caveolae-related endocytosis, reduced the AEA accumulation by half, but in combination with URB597 no further decrease was seen. Further on, the effects of genistein upon uptake were secondary to inhibition of FAAH. -

Positive Allosteric Modulators (Pams) in Mouse Models of Overt Cannabimimetic Activity, Subjective Drug Effects, and Neuropathic Pain

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2021 Investigating Cannabinoid Type-1 Receptor (CB1R) Positive Allosteric Modulators (PAMs) in Mouse Models of Overt Cannabimimetic Activity, Subjective Drug Effects, and Neuropathic Pain Jayden Elmer Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Behavioral Neurobiology Commons, Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons, Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry Commons, Nervous System Diseases Commons, and the Pharmacology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6777 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2021 Investigating Cannabinoid Type-1 Receptor (CB1R) Positive Allosteric Modulators (PAMs) in Mouse Models of Overt Cannabimimetic Activity, Subjective Drug Effects and Neuropathic Pain Jayden A. Elmer Investigating Cannabinoid Type-1 Receptor (CB1R) Positive Allosteric Modulators (PAMs) in Mouse Models of Overt Cannabimimetic Activity, Subjective Drug Effects and Neuropathic Pain A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Virginia Commonwealth University By Jayden Aric Elmer Bachelor of Science, University of Virginia, 2018 Director: Dr. Aron Lichtman, Professor, Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology; Associate Dean of Research and Graduate Studies, School of Pharmacy Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia July 2021 Acknowledgements I would first like to extend my gratitude towards the CERT program at VCU. The CERT program opened the doors for me to get involved in graduate research. -

Cannabinoid Receptor Cannabinoid Receptor

Cannabinoid Receptor Cannabinoid Receptor Cannabinoid receptors are currently classified into three groups: central (CB1), peripheral (CB2) and GPR55, all of which are G-protein-coupled. CB1 receptors are primarily located at central and peripheral nerve terminals. CB2 receptors are predominantly expressed in non-neuronal tissues, particularly immune cells, where they modulate cytokine release and cell migration. Recent reports have suggested that CB2 receptors may also be expressed in the CNS. GPR55 receptors are non-CB1/CB2 receptors that exhibit affinity for endogenous, plant and synthetic cannabinoids. Endogenous ligands for cannabinoid receptors have been discovered, including anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 Cannabinoid Receptor Antagonists, Agonists, Inhibitors, Modulators & Activators (S)-MRI-1867 (±)-Ibipinabant Cat. No.: HY-141411A ((±)-SLV319; (±)-BMS-646256) Cat. No.: HY-14791A (S)-MRI-1867 is a peripherally restricted, orally (±)-Ibipinabant ((±)-SLV319) is the racemate of bioavailable dual cannabinoid CB1 receptor and SLV319. (±)-Ibipinabant ((±)-SLV319) is a potent inducible NOS (iNOS) antagonist. (S)-MRI-1867 and selective cannabinoid-1 (CB-1) receptor ameliorates obesity-induced chronic kidney disease antagonist with an IC50 of 22 nM. (CKD). Purity: >98% Purity: 99.93% Clinical Data: No Development Reported Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 1 mg, 5 mg Size: 10 mM × 1 mL, 5 mg, 10 mg, 25 mg, 50 mg 2-Arachidonoylglycerol 2-Palmitoylglycerol Cat. No.: HY-W011051 (2-Palm-Gl) Cat. No.: HY-W013788 2-Arachidonoylglycerol is a second endogenous 2-Palmitoylglycerol (2-Palm-Gl), an congener of cannabinoid ligand in the central nervous system. 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), is a modest cannabinoid receptor CB1 agonist. 2-Palmitoylglycerol also may be an endogenous ligand for GPR119. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Neuropharmacology

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Neuropharmacology. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 January 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Neuropharmacology. 2008 January ; 54(1): 129±140. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide has effects on motivation and anxiety that are revealed by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibition Maria Schermaa,b, Julie Medaliea, Walter Frattab, Subramanian K. Vadivelc, Alexandros Makriyannisc, Daniele Piomellid, Eva Mikicse, Jozsef Hallere, Sevil Yasarf, Gianluigi Tandag, and Steven R. Goldberga,* aPreclinical Pharmacology Section, Behavioral Neuroscience Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA bB.B. Brodie Department of Neuroscience, University of Cagliari, Italy cCenter for Drug Discovery, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA dDepartment of Pharmacology, University of California, Irvine, USA eInstitute of Experimental Medicine, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary fDivision of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA gPsychobiology Section, Medications Discovery Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA Summary Converging evidence suggests that the endocannabinoid system is an important constituent of neuronal substrates involved in brain reward processes and emotional responses to stress. Here, we evaluated motivational effects of intravenously administered anandamide, an endogenous ligand for cannabinoid-CB1 receptors, in Sprague-Dawley rats, using a place-conditioning procedure in which drugs abused by humans generally produce conditioned place preferences (reward). Anandamide (0.03 to 3mg/kg intravenous) produced neither conditioned place preferences nor aversions. -

JPET 143487 Synergy Between Enzyme Inhibitors of Fatty Acid

JPET Fast Forward. Published on January 9, 2009 as DOI:10.1124/jpet.108.143487 JPET 143487 Synergy between enzyme inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase and cyclooxygenase in visceral nociception* Pattipati S. Naidu, Lamont Booker, Benjamin F. Cravatt, and Aron H. Lichtman Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Medical College of Virginia Campus, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298-0613. (P.S.N., L.B., and A.H.L.) The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Departments of Cell Biology and Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N. Torrey Pines Rd. La Jolla, CA 92037. (B.F.C.) 1 Copyright 2009 by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. JPET 143487 Running Title: Synergy between FAAH and COX inhibitors Corresponding Author: Aron H. Lichtman P.O. Box 980613 Richmond, VA 23298-0613 Telephone: 804-828-8480 Facsimile: 804-828-2117 E-mail: [email protected] Number of text pages: 16 Number of figures: 6 Number of tables: 1 Number of references: 38 Number of words in the Abstract: 247 Number of words in the Introduction: 720 Number of words in the Discussion: 1463 Abbreviations: CB1, cannabinoid receptor 1; CB2 cannabinoid receptor 2; CNS, central nervous system; FAAH, fatty acid amide hydrolase, COX, cyclooxygenase; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs; URB597, 3'-carbamoyl-biphenyl-3-yl-cyclohexylcarbamate Recommended section assignment: Behavioral pharmacology 2 JPET 143487 Abstract The present study investigated whether inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme responsible for anandamide catabolism, produces antinociception in the acetic acid- induced abdominal stretching model of visceral nociception. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of FAAH reduced acetic acid-induced abdominal stretching. -

A Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor Positive Allosteric Modulator Reduces Neuropathic Pain in the Mouse with No Psychoactive Effects

NPP-15-0045 A Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor Positive Allosteric Modulator Reduces Neuropathic Pain in the Mouse with no Psychoactive Effects 1 †Bogna M. Ignatowska-Jankowska, 5, †Gemma L. Baillie, 3Steven Kinsey, 3Molly Crowe, 1Sudeshna Ghosh, 1 Robert Allen Owens, 1M. Imad Damaj, 1Justin Poklis, 4Jenny L. Wiley, 2Matteo Zanda, 2Chiara Zanato, 2Iain R. Greig, 1††Aron H. Lichtman, 5†† Ruth A. Ross. 1 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA; 2 School of Medical Sciences, Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK; 3 Department of Psychology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA; 4 Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA; 5 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto and Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto. †Joint first authors. ††Joint corresponding authors Running Title: CB1 Allosteric Modulation 1 ABSTRACT The CB1 receptor represents a promising target for the treatment of several disorders including pain-related disease states. However, therapeutic applications of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and other CB1 orthosteric receptor agonists remain limited because of psychoactive side effects. Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) offer an alternative approach to enhance CB1 receptor function for therapeutic gain with the promise of reduced side effects. Here we describe the development of the novel synthetic CB1 PAM, 6-methyl-3-(2-nitro-1-(thiophen-2-yl)ethyl)-2- phenyl-1H-indole (ZCZ011), which augments the in vitro and in vivo pharmacological actions of the CB1 orthosteric agonists CP55,940 and N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA). ZCZ011 3 potentiated binding of [ H]CP55,940 to the CB1 receptor as well as enhancing AEA-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in mouse brain membranes and β-arrestin recruitment and ERK phosphorylation in hCB1 cells. -

Appendix-2Final.Pdf 663.7 KB

North West ‘Through the Gate Substance Misuse Services’ Drug Testing Project Appendix 2 – Analytical methodologies Overview Urine samples were analysed using three methodologies. The first methodology (General Screen) was designed to cover a wide range of analytes (drugs) and was used for all analytes other than the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs). The analyte coverage included a broad range of commonly prescribed drugs including over the counter medications, commonly misused drugs and metabolites of many of the compounds too. This approach provided a very powerful drug screening tool to investigate drug use/misuse before and whilst in prison. The second methodology (SCRA Screen) was specifically designed for SCRAs and targets only those compounds. This was a very sensitive methodology with a method capability of sub 100pg/ml for over 600 SCRAs and their metabolites. Both methodologies utilised full scan high resolution accurate mass LCMS technologies that allowed a non-targeted approach to data acquisition and the ability to retrospectively review data. The non-targeted approach to data acquisition effectively means that the analyte coverage of the data acquisition was unlimited. The only limiting factors were related to the chemical nature of the analyte being looked for. The analyte must extract in the sample preparation process; it must chromatograph and it must ionise under the conditions used by the mass spectrometer interface. The final limiting factor was presence in the data processing database. The subsequent study of negative MDT samples across the North West and London and the South East used a GCMS methodology for anabolic steroids in addition to the General and SCRA screens. -

Behavioral and Electrophysiological Effects of Endocannabinoid and Dopaminergic Systems on Salient Stimuli

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 19 May 2014 BEHAVIORAL NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00183 Behavioral and electrophysiological effects of endocannabinoid and dopaminergic systems on salient stimuli Daniela Laricchiuta 1,2*, Alessandra Musella 1,3, Silvia Rossi 1,3 and Diego Centonze 1,3 1 IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome, Italy 2 Dipartimento di Psicologia, Facoltà di Medicina e Psicologia, Università “Sapienza” di Roma, Rome, Italy 3 Dipartimento di Neuroscienze, Università Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy Edited by: Rewarding effects have been related to enhanced dopamine (DA) release in James P.Herman, University of corticolimbic and basal ganglia structures. The DAergic and endocannabinoid interaction Cincinnati, USA in the responses to reward is described. This study investigated the link between Reviewed by: Gregg Stanwood, Vanderbilt endocannabinoid and DAergic transmission in the processes that are related to response University, USA to two types of reward, palatable food and novelty. Mice treated with drugs acting on Steven R. Laviolette, University of endocannabinoid system (ECS) (URB597, AM251) or DAergic system (haloperidol) were Western Ontario, Canada submitted to approach-avoidance conflict tasks with palatable food or novelty. In the same *Correspondence: mice, the cannabinoid type-1 (CB1)-mediated GABAergic transmission in medium spiny Daniela Laricchiuta, Dipartimento di Psicologia, Facoltà di Medicina e neurons -

Cannabinoid Antagonist Drug Discrimination in Nonhuman Primates

1521-0103/372/1/119–127$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.119.261818 THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS J Pharmacol Exp Ther 372:119–127, January 2020 Copyright ª 2019 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Cannabinoid Antagonist Drug Discrimination in Nonhuman Primates Brian D. Kangas, Ani S. Zakarian, Kiran Vemuri, Shakiru O. Alapafuja, Shan Jiang, Spyros P. Nikas, Alexandros Makriyannis, and Jack Bergman Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (B.D.K., J.B.); Behavioral Biology Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts (B.D.K., A.S.Z., J.B.); and Center for Drug Discovery, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts (K.V., S.O.A., S.J., S.P.N., A.M.) Received July 29, 2019; accepted October 21, 2019 Downloaded from ABSTRACT Despite a growing acceptance that withdrawal symptoms can inhibitors AM3506 (0.3–5.6 mg/kg), URB597 (3.0–5.6 mg/kg), and emerge following discontinuation of cannabis products, espe- nonselective FAAH/MGL inhibitor AM4302 (3.0–10.0 mg/kg) cially in high-intake chronic users, there are no Food and Drug revealed that only agonists with CB1 affinity were able to Administration (FDA)–approved treatment options. Drug devel- reduce the rimonabant-like discriminative stimulus effects opment has been hampered by difficulties studying cannabis of withholding daily agonist treatment. Although the pres- jpet.aspetjournals.org withdrawal in laboratory animals. One preclinical approach that ent studies did not document physiologic disturbances has been effective in studying withdrawal from drugs in several associated with withdrawal, the results are consistent pharmacological classes is antagonist drug discrimination.