Hello, Ruel World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership

NORTHERN BRIDGE DOCTORAL TRAINING PARTNERSHIP PHD STUDENTSHIPS IN SPANISH, PORTUGUESE AND LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES CLOSING DATE: AT NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY. 13/JANUARY/2020 The Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership invites top-calibre applicants to apply to its 2020/2021 doctoral studentships competi- tion. Up to 67 fully-funded doctoral studentships are available across the full range of arts and humanities subjects, including: Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies. The Northern Bridge is an exciting, AHRC-funded collaboration between: Newcastle University, Durham University, Queen’s University Belfast, Ulster University, Northumbria University, Sunderland University, and Teesside University. Our aim is to deliver outstanding doctoral education in the arts and humanities, and successful applicants will join a thriving cohort of almost ffty Northern Bridge PhD students recruited through last year’s studentship com- petition. WHY CHOOSE US Northern Bridge ofers exceptional supervision by aca- demic staf researching at the cutting edge of their disci- plines, vibrant research environments that promote inter- disciplinary enquiry, and research training and career development opportunities tailored to the needs of twenty-frst-century researchers. SUPERVISION AREAS Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin American Studies ofers supervision in the following areas: SPANISH, PORTUGUESE, AND LATIN AMERICAN CULTURAL HISTORY AND POPULAR CULTURE. Dr Jorge Catalá-Carrasco, Dr Nick Morgan, Dr Patricia Oliart, Dr Dunja Fehimović and Dr Fernando Beleza. DISCOURSES OF RACE AND IDENTITY IN LATIN AMERICA. Prof Rosaleen Howard, Dr Patricia Oliart, Dr Nick Morgan, Dr Dunja Fehimović and Dr Fernando Beleza. LATIN AMERICAN FILM, LITERATURE AND THEATRE. Dr Philippa Page, Dr Dunja Fehimović and Dr Fernando Beleza. HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN 19TH- AND 20TH-CENTURY LATIN AMERICA. -

Dying to Come Back As a Memoir

Youth, Middle-Age, and You-Look-Great Stephen Rosen Dying to come back as a Memoir When George Gershwin asked to study composition with Maurice Ravel, Ravel replied, “Why be a second- rate Ravel when you can be a first-rate Gershwin?” a I much prefer that my own style be my own, uncultivated and rude, but made to fit as a garment, to the measure of my mind rather than someone else’s, which may be more elegant, ambitious, and adorned but one that deriving from a greater genius, continually slips off, Copyright © 2013 by Stephen Rosen. All rights reserved. unfitted to the humble proportions of my intellect. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any --Petrarch means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author. a Disclaimer: This book is based on fallible memory and many of the stories did not “Is it true, Rabbi, that ‘Do unto others as you would have them actually happen the way I describe them; portrayals of individuals and events contain motivated misperceptions, selective recall, confirmation biases, irony, and inventive or do unto you’ summarizes all of the Torah’s wisdom, and all imaginative recreations that make me appear wiser and more heroic or than I actually Jewish ethical and moral teachings?” was or am. --Astrophysicist PROSPECT PRESS 7 Prospect Boulevard East Hampton, NY 11937 and “Well, let me answer your question with a question. Is it true that 35 West 81st Street, Suite 1D all -

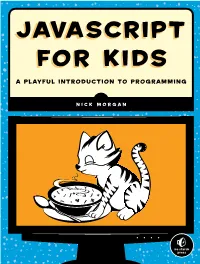

Javascript for Kids

For kids aged 10+ (and their parents) rReEaAlL pPrrooggrraammmmiinngg.. J R EAL EA SY. J Java Script r eal ea sy. av Java Script av Illustrations by Miran Lipovaca JavaScript is the programming language of With visual examples like bouncing balls, ascript for kids aScript for Kids the Internet, the secret sauce that makes the animated bees, and racing cars, you can really FFOORR KKIIDDSS Web awesome, your favorite sites interactive, see what you’re programming. Each chapter and online games fun! builds on the last, and programming challenges JavaScript for Kids is a lighthearted intro- at the end of each chapter will stretch your A Pl ay fu l I ntro du ctio n to Pro g r am min g duction that teaches programming essentials brain and inspire your own amazing programs. through patient, step-by-step examples paired Make something cool with JavaScript today! with funny illustrations. You’ll begin with ABOUT THE AUTHOR the basics, like working with strings, arrays, Nick Morgan and loops, and then move on to more advanced Nick Morgan is a frontend engineer at topics, like building interactivity with jQuery Twitter. He loves all programming languages and drawing graphics with Canvas. but has a particular soft spot for JavaScript. Along the way, you’ll write games such as Nick lives in San Francisco (the foggy part) Find the Buried Treasure, Hangman, and with his fiancée and their fluffy dog, Pancake. Snake. You’ll also learn how to: He blogs at skilldrick.co.uk. Create functions to organize and reuse your code Write and modify HTML to create dynamic web pages Use the DOM and jQuery to make your web pages react to user input Use the Canvas element to draw and animate graphics Program real user-controlled games with collision detection and score keeping Morgan P S H R O E L $34.95 ($36.95 CDN) G V R E A I M N M : I N G LANGUAGES/JAVASCRIPT www.nostarch.com TH E FINEST I N G EEK ENTERTAI N M ENT ™ JavaScript for Kids JavaScript for Kids A Playful Introduction to Programming By Nick Morgan San Francisco JAVASCRIPT FOR KIDS. -

Sneak Preview

Sneak Preview Management Communication An Anthology: Revised Second Edition Edited by Farrokh Moshiri Included in this preview: • Copyright Page • Table of Contents • Excerpt of Chapter 1 For additional information on adopting this book for your class, please contact us at 800.200.3908 x501 or via e-mail at [email protected] Sneak Preview Management Communication An Anthology Revised Second Edition Edited by Farrokh Moshiri University of California, Riverside Copyright © 2011 by Farrokh Moshiri. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfi lming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of University Readers, Inc. First published in the United States of America in 2010 by Cognella, a division of University Readers, Inc. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-60927-925-7 Contents Introduction 1 SECTION ONE COMMUNICATING WITH THE PUBLIC: PUBLIC SPEAKING, ORAL PRESENTATIONS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS Public Speaking and Oral Presentation Skills: Introduction 7 How to Become an Authentic Speaker 9 By Nick Morgan Th e Kinesthetic Speaker: Putting Action into Words 17 By Nick Morgan Listening to People 29 By Ralph G. Nichols and Leonard A. Stevens Message Credibility: How Public Relations Can Enhance Communication 43 By Heather Ilizaliturri SECTION TWO TEAMS AND TEAM MANAGEMENT Teams and Team Management: Introduction 49 Managing Virtual Teams: Getting the Most from Wikis, Blogs, and Other Collaborative Tools 53 By M. -

Australian Humanities Review

AUSTRALIAN HUMANITIES REVIEW issue 47 2009 Edited by Monique Rooney and Russell Smith Australian Humanities Review Editors: Monique Rooney, The Australian National University Russell Smith, The Australian National University Consulting Editors: Lucy Frost, University of Tasmania Elizabeth McMahon, University of New South Wales Cassandra Pybus, University of Tasmania Editorial Advisors: Stuart Cunningham, Queensland University of Technology Guy Davidson, University of Wollongong Ken Gelder, University of Melbourne Andrew Hassam, Monash University Marilyn Lake, La Trobe University Sue Martin, La Trobe University Fiona Probyn-Rapsey, University of Sydney Libby Robin, The Australian National University Deborah Rose, The Australian National University Susan Sheridan, Flinders University Rosalind Smith, University of Newcastle Terry Threadgold, Cardiff University, Wales McKenzie Wark, Eugene Lang College, New York Terri-Ann White, University of Western Australia Adi Wimmer, University of Klagenfurt, Austria Australian Humanities Review is published by the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, with the support of the School of Humanities at The Australian National University. Mailing address: Editors, Australian Humanities Review, School of Humanities, AD Hope Building #14, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia. Email: [email protected] Website: www.australianhumanitiesreview.org Published by ANU E Press Email: [email protected] Website: http://epress.anu.edu.au © The Australian National University. This Publication is protected by copyright and may be used as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 provided appropriate acknowledgment of the source is published. The illustrations and certain identified inclusions in the text are held under separate copyrights and may not be reproduced in any form without the permission of the respective copyright holders. -

Make Yourself Heard! Friday, March 18, 2016 1:00-4:00 PM Marriott Newport Beach Hotel & Spa

Make Yourself Heard! Friday, March 18, 2016 1:00-4:00 PM Marriott Newport Beach Hotel & Spa In the rapidly changing healthcare environment, the need for NPs to be effective public speakers is more critical than ever. This interactive session will motivate NPs to improve their public speaking skills by 1) reviewing why NPs need effective presentation skills, 2) teaching effective public-speaking skills, and 3) providing an opportunity to practice in a safe, fun environment. The presenters will review tips for effective public speaking and model behaviors that will enable participants to make their next presentations better than their last. Workshop participants will receive pre-session materials to assist them in workshop preparation. During the workshop, participants will use strategies learned to develop a 5-minute presentation on a topic of their choosing; and receive feedback from facilitators and peers. At the end of this session, participants will be able to: Organize a presentation with particular emphasis on an effective opening and a strong closing. Demonstrate at least 3 skills of effective presentations. Create and deliver an effective 5-minute presentation. Constructively critique the presentations of peer participants. Discuss application of techniques learned in the session to create and deliver their next presentation more effectively. Virginia McCoy Hass, DNP, FNP-C, PA-C [email protected] Donna Emmanuel, DNP, FNP-BC, FAANP [email protected] Vanessa Parker, PhD, MA, MSN, RN, CHES, PHN, PMHNP-BC [email protected] -

Non-Verbal Communication

Non-verbal communication Every communication is two conversations: the verbal and non-verbal. When the two conversations are not aligned, people believe the non-verbal every time – Dr Nick Morgan You might be surprised to learn that between 60 Body movements and 90 per cent of communication is non-verbal. Body movements can convey intent, emotion and It is important to be aware of your non-verbal meaning, such as shaking or nodding your head. It communication so you don’t undermine your can show how people feel or think about you. verbal communication. Your audience’s non- Too many body movements can be distracting – verbal communication gives you clues about how for example, too many hand gestures can be off- your messages are being received which gives you putting and pointing your finger can be offensive. an opportunity to modify your messages. Posture Non-verbal communication varies between How you stand or sit, such as whether your cultures and country of origin. For example, in arms and legs are crossed, determines whether most Western cultures eye contact is a good thing. your posture is open or closed. Posture can It shows attentiveness, confidence and honesty. In communicate: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic and Native American cultures, • mental status – for example, defeated eye contact can be seen as disrespectful. • physical condition – for example, slouching can indicate tiredness Types of non-verbal communication The different types of non-verbal communication include: First impressions It takes one tenth of a second for someone to make their first impression. -

State Room 4

Friday November 17, 2017 7:00 AM State Room 4 - Third Floor (Conference 201016 7:00 AM to 7:45 AM Sheraton Center) Community College Section Business Meeting - Part I Sponsor: Community College Section Presenters: Jeannie Hunt, Northwest College Terry L. Rogers, Casper College Jessica R. Hurless, Skyline College 201031 7:00 AM to 7:45 AM Sheraton Live Oak -Second Floor NCA Distinguished Scholars Business Meeting Sponsor: NCA National Office 201042 7:00 AM to 7:45 AM Sheraton Majestic 1 - 37th Floor (Center Tower) Experiential Learning in Communication Division Business Meeting Sponsor: Experiential Learning in Communication Division Presenters: Elizabeth Tolman, South Dakota State University Angela M. Corbo, Widener University Brandy Fair, Grayson College 201044 7:00 AM to 7:45 AM Sheraton Majestic 3 - 37th Floor (Center Tower) Communication and the Future Division Business Meeting Sponsor: Communication and the Future Division Presenters: Ryan C. Wallace, California State University, East Bay Aubrie Serena Adams, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Roseann E. Pluretti, University of Kansas Shannon C. VanHorn, Valley City State University Alison Nicole Novak, Rowan University 201066 7:00 AM to 7:45 AM Marriott Nice - Third Floor Kenneth Burke Society Business Meeting Sponsor: Kenneth Burke Society Presenters: Erik Garrett, Duquesne University Annie Laurie Nichols, University of Maryland 201069 7:00 AM to 7:45 AM Off Site Off Site Women's Caucus and Feminist and Women Studies Division Officers' Breakfast Meeting Sponsors: Feminist and Women Studies Division; Women's Caucus Presenters: Michelle Calka, Manchester University Jessica Kratzer, Northern Kentucky University Kathleen E. Feyh, Syracuse University Elizabeth F. -

Limited Trading As Aql Mr Martin John

qryExportToContactsXLS Communications Provider Full Name (aq) Limited trading as aql Mr Martin John (aq) Networks Limited Ms Melissa Sherriff 08Direct Limited Mr Richard Griffiths 10ACT Limited Mr Andrew Baker 118 Limited Ms Emma Knight 2 Ergo Limited Mr Alan Leitch 24 Seven Communications Ltd Mr David Samuel 2Communications Limited Mr Tony McCann 2-Sell-It Ltd Mr Ray Barry 42 Telecom UK Limited Mr Johan Persson 4D Interactive Ltd Mr Nick Morgan A2B Telecom Limited Mr Lawrence Bingham Abel & Co (Scotland) Ltd Mr Max Ramyar ACN European Services Ltd Mr Paul Gagnier Affiniti Integrated Solutions Ltd Ms Lesa Green Aggregated Telecom Ltd Mr Phil O'Keeffe Airwave Solutions Ltd Mr Ian MacIver Aloha Telecommunications Mr Nathaniel Limited McInnes Alphatalk Ltd Mr Zafar Majid alwaysON Ltd Mr David Paulino Annecto Telecom Mr Franck Zaire API Telecom Limited Mr Nicholas Holland Atlantic Communications Corp Mr Chris Abbassy Ltd Atlas Interactive Group Limited Mrs Sue Hobson Bangla Trac Communication Mr Zainal Abedin Ltd Page 1 qryExportToContactsXLS Barritec Limited Miss Annabel Bowe Barritel Limited Miss Annabel Bowe Bellingham Mr James Parfrey Telecommunications Limited Bharti Airtel UK Limited Mr V Seetthraman Bicom Systems EURL Mr Nihad Skaljo British Sky Broadcasting Mr Paul King Limited Broadcast Telecom Ltd Mr Germaine Malcomb BT OnePhone Limited Mr Magnus Kelly Budget Numbers Ltd Mr James Goddard Business Broadcast Ms Victoria Harris Communications Ltd Business Service Provision Mr Anthony Company Limited Amissah Buzz Networks Limited Mr -

Hearing Impairment and Elderly People

Hearing Impairment and Elderly People May 1986 NTIS order #PB86-218559 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Hearing Impairment and Elderly People–A Background Paper, OTA-BP-BA-30 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, May 1986). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 86-600511 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents US. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 Preface Hearing impairment is very common among elderly people and can seriously affect their quality of life, personal safety, and ability to function independently. This OTA background paper discusses the prevalence of hearing impairment and its impact on elderly people; hearing devices and services that may benefit them; and problems in the service delivery system that limit access to these devices and services. This background paper is part of the OTA assessment of Technology and Aging in America that was requested by the Senate Special Committee on Aging and the House Select Committee on Aging, and endorsed by the House Committee on Education and Labor. For that assessment OTA selected five chronic conditions for in-depth analysis because of their prevalence and severe impact on elderly people and because of the potential role of technology in their treatment. Hearing impairment is one of these con- ditions; the others are dementia, urinary incontinence, osteoarthritis, and osteoporosis. Many of the chronic conditions that affect elderly people, including the types of hearing impairment that are most common, cannot be cured with available medical and surgical treatments, As a result, some elderly people, their families, and others assume that these conditions are not treatable. -

ENGL 201 Year: 2021-2022 Course Title: Public Speaking Credit Hours: 3

Tompkins Cortland Community College Master Course Syllabus Course Discipline and Number: ENGL 201 Year: 2021-2022 Course Title: Public Speaking Credit Hours: 3 I. Course Description: Public speaking is designed for students from any discipline at any level to improve skills for speeches and oral presentations. Analyzing and adapting to different audiences, purposes, and situations is required. A primary focus of the course will be selecting and organizing information into effective and ethical speeches while using available technology to enhance presentations. The course offers an opportunity for practice and discussion of the role of research, civility and diversity in public discourse, and delivery strategies. ENGL 201 fulfills the SUNY General Education Basic Communication requirement for oral skills. Prerequisite: Prior completion of, or concurrent enrollment in, ENGL 100. 3 Cr. (3 Lec.) Fall and spring semesters. II. Additional Course Information: 1. This course is offered in both face-to- face and online formats. FOR ONLINE SECTIONS: 2. Students must have sufficient internet connection to sustain weekly asynchronous classwork on Blackboard. 3. Students must be able to record their own speeches via phone, computer, or camera. 4. Students will use a third-party site of their choice, such as Vimeo, YouTube, or Flipgrid, to upload their speeches. III. Student Learning Outcomes Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to: 1. Create an organized oral presentation of a researched argument that adapts to a specific audience, situation, and purpose. 2. Deliver oral presentations proficiently with clarity and confidence. 3. Use the characteristics of valid arguments and ethical discourse to create an argument. -

Qryexporttocontactsxls Page 1 Communications Provider Full Name

qryExportToContactsXLS Communications Provider Full Name (aq) Networks Limited Ms Melissa Sherriff 08Direct Limited Mr Richard Griffiths 10ACT Limited Mr Andrew Baker 118 Limited Ms Emma Knight 1RT Group Ltd Mr Jody Rhodes 2 Ergo Limited Mr Alan Leitch 24 Seven Communications Ltd Mr David Samuel 2Communications Limited Mr Tony McCann 2-Sell-It Ltd Mr Ray Barry 42 Telecom UK Limited Mr Johan Persson 4D Interactive Ltd Mr Nick Morgan A2B Telecom Limited Mr Lawrence Bingham Abel & Co (Scotland) Ltd Mr Max Ramyar ACN European Services Ltd Mr Paul Gagnier Affiniti Integrated Solutions Ltd Ms Lesa Green Aggregated Telecom Ltd Mr Phil O'Keeffe Airwave Solutions Ltd Mr Ian MacIver Aloha Telecommunications Mr Nathaniel Limited McInnes Alphatalk Ltd Mr Zafar Majid alwaysON Ltd Mr Omair Sheikh Annecto Telecom Mr Franck Zaire API Telecom Limited Mr Nicholas Holland Atlantic Communications Corp Mr John Stevens - Ltd D.O.B 05/07/1952 Atlantic Communications Corp Mr Ansar Ltd Mahmood Atlas Interactive Group Limited Mrs Sue Hobson Page 1 qryExportToContactsXLS Bangla Trac Communication Mr Zainal Abedin Ltd Bellingham Mr James Parfrey Telecommunications Limited Bharti Airtel UK Limited Mr V Seetthraman British Sky Broadcasting Mr Paul King Limited Broadcast Telecom Ltd Mr Germaine Malcomb BT Mr Michael Attwell BT OnePhone Limited Mr Magnus Kelly Budget Numbers Ltd Mr James Goddard Business Broadcast Ms Victoria Harris Communications Ltd Business Service Provision Mr Anthony Company Limited Amissah Buzz Networks Limited Mr Steven King Cable & Wireless