Juglans Regia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Colourants with Ancient Concept and Probable Uses

JOURNAL OF ADVANCED BOTANY AND ZOOLOGY Journal homepage: http://scienceq.org/Journals/JABZ.php Review Open Access Natural Colourants With Ancient Concept and Probable Uses Tabassum Khair1, Sujoy Bhusan2, Koushik Choudhury2, Ratna Choudhury3, Manabendra Debnath4 and Biplab De2* 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India. 2 Regional Institute of Pharmaceutical Science And Technology, Abhoynagar, Agartala, Tripura, India. 3 Rajnagar H. S. School, Agartala, Tripura, India. 4 Department of Human Physiology, Swami Vivekananda Mahavidyalaya, Mohanpur, Tripura, India. *Corresponding author: Biplab De, E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 20, 2017, Accepted: April 15, 2017, Published: April 15, 2017. ABSTRACT: The majority of natural colourants are of vegetable origin from plant sources –roots, berries, barks, leaves, wood and other organic sources such as fungi and lichens. In the medicinal and food products apart from active constituents there are several other ingredients present which are used for either ethical or technical reasons. Colouring agent is one of them, known as excipients. The discovery of man-made synthetic dye in the mid-19th century triggered a long decline in the large-scale market for natural dyes as practiced by the villagers and tribes. The continuous use of synthetic colours in textile and food industry has been found to be detrimental to human health, also leading to environmental degradation. Biocolours are extracted by the villagers and certain tribes from natural herbs, plants as leaves, fruits (rind or seeds), flowers (petals, stamens), bark or roots, minerals such as prussian blue, red ochre & ultramarine blue and are also of insect origin such as lac, cochineal and kermes. -

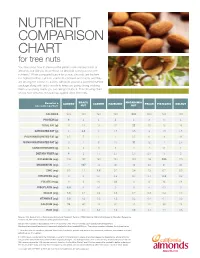

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Pistachio and Walnut Development Project TCP/KYR/3203 (D)

State Agency of Forestry and Environmental Protection, Kyrgyz Republic Pistachio and Walnut Development Project TCP/KYR/3203 (D) Hafiz Muminjanov Plant Production & Protection Officer Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Sub-regional Office for Central Asia (FAOSEC) Agriculture in Kyrgyz Republic • Cereals - 1.5 mln MT, • including wheat 0.7 mln. MT • Potato - 1. 3 mln. MT • Vegetables - 0.8 mln. MT • Fruits -200 000 MT • Grapes - 10 000 MT 1 Why pistachio and walnut? Total Plantation Production, Yield, Area, ha Area, ha MT kg/ha Pistachio 57 000 12000 1 000 15-20 Walnut 47 000 - 900-1 900 20-40 Agriculture growth vs Overall Growth Kyrgyz Republic - Ag. Growth Vs. Overall Growth 160 Total GDP (1990=100) 140 AgGDP (1990=100) Total GDP (2002=100) AgGDP (2002=100) 120 100 AgGDP 80 (1990=100) Total GDP 60 (1990=100) 40 2 Wheat Grain Trade Balance ('000 tons) 1,200 1,000 800 600 Import 400 Domestic Production 200 - 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Trade Balance Values Dry Nuts Vs. Agriculture (2001 = 100) 600 Dry Nuts 400 200 0 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 - 200 - 400 Agriculture - 600 3 Why pistachio and walnut? • Central Asia – centre of origin & diversity of nuts • Large area of forest plantations • Suitable climatic conditions (dry summer) • Suitable socio-economic environment • Organic forests 4 Why pistachio and walnut? • Absence of market orientation in the past • Current varieties not valued for international market • No management done (cutting, pruning, etc.) • Density is high, pistachio male/female ratio not regulated • Yield is low • History of quality produce • International standards (USA, France, Chile, Australia) • Demand increase • Potential for export • Increasing farmers income & Livelihood improvement 5 Why pistachio and walnut? Development of the nut fruit sector has a high potential in improving livelihood and food security due the high international demand… Past and Related Work • Tien Shan Ecosystem Development Project (IFAD; GEF; WB-Bio Carbon Fund; Japanese Government). -

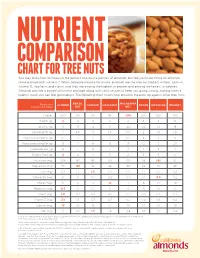

Chart for Tree Nuts

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART FOR TREE NUTS You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the highest in protein and among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a healthy snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT Calories 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 Protein (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 Total Fat (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 18 Saturated Fat (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 Polyunsaturated Fat (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 Monounsaturated Fat (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 Carbohydrates (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 Dietary Fiber (g) 4 2 1 3 2 3 3 2 Potassium (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 Magnesium (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 Zinc (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 Vitamin B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 Folate (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 Riboflavin (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 Niacin (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 Vitamin E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 Calcium (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 Iron (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Conservation Assessment for Butternut Or White Walnut (Juglans Cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region

Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2003 Jan Schultz Hiawatha National Forest Forest Plant Ecologist (906) 228-8491 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Juglans cinerea L. (butternut). This is an administrative review of existing information only and does not represent a management decision or direction by the U. S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was gathered and reported in preparation of this document, then subsequently reviewed by subject experts, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if the reader has information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. 2 Table Of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION / OBJECTIVES.......................................................................7 BIOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION..............................8 Species Description and Life History..........................................................................................8 SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS...........................................................................9 -

Juglans Nigra Juglandaceae L

Juglans nigra L. Juglandaceae LOCAL NAMES English (walnut,American walnut,eastern black walnut,black walnut); French (noyer noir); German (schwarze Walnuß); Portuguese (nogueira- preta); Spanish (nogal negro,nogal Americano) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Black walnut is a deciduous tree that grows to a height of 46 m but ordinarily grows to around 25 m and up to 102 cm dbh. Black walnut develops a long, smooth trunk and a small rounded crown. In the open, the trunk forks low with a few ascending and spreading coarse branches. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. The root system usually consists of a deep taproot and several wide- 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office spreading lateral roots. guide to plant species) Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, 30-70 cm long, up to 23 leaflets, leaflets are up to 13 cm long, serrated, dark green with a yellow fall colour in autumn and emits a pleasant sweet though resinous smell when crushed or bruised. Flowers monoecious, male flowers catkins, small scaley, cone-like buds; female flowers up to 8-flowered spikes. Fruit a drupe-like nut surrounded by a fleshy, indehiscent exocarp. The nut has a rough, furrowed, hard shell that protects the edible seed. Fruits Bark (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office produced in clusters of 2-3 and borne on the terminals of the current guide to plant species) season's growth. The seed is sweet, oily and high in protein. The bitter tasting bark on young trees is dark and scaly becoming darker with rounded intersecting ridges on maturity. BIOLOGY Flowers begin to appear mid-April in the south and progressively later until early June in the northern part of the natural range. -

Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes

life Article Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes Paulo A. Zaini 1, Noah G. Feinberg 1, Filipa S. Grilo 2 , Houston J. Saxe 1 , Michelle R. Salemi 3, Brett S. Phinney 3 , Carlos H. Crisosto 1 and Abhaya M. Dandekar 1,* 1 Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (P.A.Z.); [email protected] (N.G.F.); [email protected] (H.J.S.); [email protected] (C.H.C.) 2 Department of Food Sciences and Technology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] 3 Proteomics Core Facility, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (M.R.S.); [email protected] (B.S.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Walnuts (Juglans regia L.) are a valuable dietary source of polyphenols and lipids, with increasing worldwide consumption. California is a major producer, with ‘Chandler’ and ‘Tulare’ among the cultivars more widely grown. ‘Chandler’ produces kernels with extra light color at a higher frequency than other cultivars, gaining preference by growers and consumers. Here we performed a deep comparative proteome analysis of kernel pellicle tissue from these two valued genotypes at three harvest maturities, detecting a total of 4937 J. regia proteins. Late and early maturity stages were compared for each cultivar, revealing many developmental responses common or specific for each cultivar. Top protein biomarkers for each developmental stage were also selected based on larger fold-change differences and lower variance among replicates, including proteins for biosynthesis of lipids and phenols, defense-related proteins and desiccation stress-related proteins. -

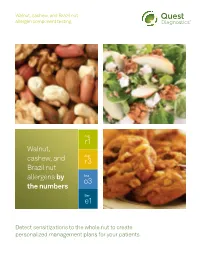

Tree Nut Allergen Component Testing Brochure

Walnut, cashew, and Brazil nut allergen component testing Jug r1 Walnut, Jug cashew, and r3 Brazil nut allergens by Ana o3 the numbers Ber e1 Detect sensitizations to the whole nut to create personalized management plans for your patients. Allergen component testing Measurement of specific IgE by blood test that provides objective assessment of sensitization to the whole nut protein is the first step in discovering the likelihood of a systemic reaction and the necessary precautions that may be prescribed. Walnut TC 3489 One of the most common causes WHOLE of allergic reactions to tree nuts.1,2 Walnut ALLERGEN • Estimated prevalence of walnut allergy in the general population is up to 0.7%.2 • Potentially life-threatening, increasing in prevalence and rarely outgrown.2,3 Associated with systemic Jug reactions2 r1 • Storage protein (2s albumin) 3,4 4 ALLERGEN • Heat and digestion stable COMPONENTS • Highly abundant in walnut Associated with local and Jug systemic reactions2 r3 • Lipid transfer protein (LTP)1,4 • Heat and digestion stable Knowing which Positive whole walnut with negative protein your patient is Jug r1 and Jug r3 results may be explained by sensitization to6: sensitized to can help • Other walnut storage proteins you develop a • Pollen proteins like profilin or PR-10 proteins management plan. • CCD (cross-reacting carbohydrate determinants) Cashew nut Brazil nut TC 2608 TC 2818 Allergy on the rise with increased Hidden allergen often found Cashew consumption in snack foods, Asian Brazil in cookies, insect repellent foods, baked goods, nut butters and and beauty products.12 pestos.8,9 • Extensive cross-reactivity within • Sensitized patients have a risk of experiencing the family can be expected.13 severe allergic reactions; the risk has been • Generally persists and is potentially reported to be even higher than for peanut life-threatening.14 allergic patients (74% vs. -

Juglans Spp., Juglone and Allelopathy

AllelopathyJournatT(l) l-55 (2000) O Inrernationa,^,,r,':'r::;:';::::,:rt;SS Juglansspp., juglone and allelopathy R.J.WILLIS Schoolof Botany.L.iniversity of Melbourre,Parkville, Victoria 3052, ALrstr.alia (Receivedin revisedform : February 26.1999) CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. HistoricalBackground 3. The Effectsof walnutson otherplants 3.i. Juglansnigra 3.1.1.Effects on cropplants 3. I .2. Eft'ectson co-plantedtrees 3. 1 .3 . Effectson naturalvegetation 3.2. Juglansregia 3.2.1. Effectson otherplalrts 3.2.2.Effects on phytoplankton 1.3. Othel walnuts : Juglans'cinerea, J. ntttlor.J. mandshw-icu 4. Juglone 5. Variability in the effect of walnut 5.1. Intraspecificand Interspecific variation 5.2. Seasonalvariation 5.3 Variation in the effect of Juglansnigra on other.plants 5.4. Soil effects 6. Discussion Ke1'rvords: Allelopathy,crops, history, Juglan.s spp., juglone. phytoplankton,walnut, soil, TTCCS 1. INTRODUCTION The"rvalnuts" are referable to Juglans,a genusof 20-25species with a naturaldistribution acrossthe Northern Hemisphere and extending into SouthAmerica. Juglans is a memberof thefamily Juglandaceae which contains6 or 7 additionalgenera including Cruv,a, Cryptocctrva and a total of about 60 species. Walnuts are corrunerciallyimportant as the sourceof the ediblewalnut, the highly prizedtimber and as a specimentrees. Eating walnutsare usually obtarnedfrom -/. regia (the colrunonor Persianwalnut, erroneousll'known as the English walnut)- a nativeof SEEurope and Asia, which haslong been cultivated, but arealso sometin.res availablelocally from other speciessuch as J. nigra (back walnut) - a native of eastern North America andJ. ntajor, J. calfornica andJ. hindsii, native to the u,esternu.S. ILillis Grafting of supcrior fnrit-bearing scions of J. regia onlo rootstocksof hlrdier spccics. -

Black Walnut Juglans Nigra

black walnut Juglans nigra Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliophyta The deciduous black walnut tree may grow to a Class: Magnoliopsida height of 150 feet and a diameter of five feet. The Order: Fagales trunk is straight, and the crown is rounded. The bark is thick, black and deeply furrowed. The pith in the Family: Juglandaceae twigs is chambered, that is, divided by partitions. ILLINOIS STATUS The bud is rounded at the tip, pale brown and hairy. The pinnately compound leaves have 15 to 23 common, native leaflets and are arranged alternately on the stem. © Guy Sternberg Each lance-shaped leaflet may be up to three and one-half inches long and one and one-half inches wide. The leaflet is toothed along the edges, yellow- green and smooth above and paler and hairy below. Leaves turn yellow in the fall. Male and female flowers are separate but located on the same tree. The male (staminate) flowers are arranged in yellow- green, hairy catkins, while the female (pistillate) flowers are in small spikes. Neither type of flower has petals. The spherical fruits are arranged in groups of one or two. Each green or yellow-green walnut may be up to two inches in diameter. The husk on the fruit is thick, while the nut is very hard, oval, dark brown and deeply ridged. The seed is sweet to the taste. tree in summer BEHAVIORS The black walnut may be found statewide in Illinois. ILLINOIS RANGE This tree grows in rich woodlands. The black walnut flowers in April and May when the leaves are partly grown. -

Wood Identification and Chemistry' Covers the Physicalproperties and Structural Features of Hardwoods and Softwoods

11 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 031 555 VT 007 853 Woodworking Technology. San Diego State Coll., Calif. Dept. of Industrial Arts. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEA Washington, D.C. Pub Date Aug 68 Note-252p.; Materials developed at NDEA Inst. for Advanced Studyin Industrial Arts (San Diego, June 24 -Au9ust 2, 1968). EDRS Price MF -$1.00 He -$13.20 Descriptors-Curriculum Development, *Industrial Arts, Instructional Materials, Learning Activities, Lesson Plans, Lumber Industry, Resource Materials, *Resource Units, Summer Institutes, Teaching Codes, *Units of Study (Sublect Fields), *Woodworking Identifiers-*National Defense Education Act TitleXIInstitute, NDEA TitleXIInstitute, Woodworking Technology SIX teaching units which were developed by the 24 institute participantsare given. "Wood Identification and Chemistry' covers the physicalproperties and structural features of hardwoods and softwoods. "Seasoning" explainsair drying, kiln drying, and seven special lumber seasoning processes. "Researchon Laminates" describes the bending of solid wood and wood laminates, beam lamination, lamination adhesives,. andplasticlaminates."Particleboard:ATeachingUnitexplains particleboard manufacturing and the several classes of particleboard and theiruses. "Lumber Merchandising" outhnes lumber grades andsome wood byproducts. "A Teaching Unitin Physical Testing of Joints, Finishes, Adhesives, and Fasterners" describes tests of four common edge pints, finishes, wood adhesives, and wood screws Each of these units includes a bibhography, glossary, and student exercises (EM) M 55, ...k.",z<ONR; z _: , , . "'zr ss\ ss s:Ts s , s' !, , , , zs "" z' s: - 55 Ts 5. , -5, 5,5 . 5, :5,5, s s``s ss ' ,,, 4 ;.< ,s ssA 11111.116; \ ss s, : , \s, s's \ , , 's's \ sz z, ;.:4 1;y: SS lza'itVs."4,z ...':',\\Z'z.,'I,,\ "t"-...,,, `,. -

Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids

Purdue University Purdue extension FNR-420-W & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids Lenny Farlee1,3, Keith Woeste1, Michael Ostry2, James McKenna1 and Sally Weeks3 1 USDA Forest Service Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY 2 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 1561 Lindig Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 Introduction Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as white walnut, is a native hardwood related to black walnut (Juglans nigra) and other members of the walnut family. Butternut is a medium-sized tree with alternate, pinnately compound leaves that bears large, sharply ridged and corrugated, elongated, cylindrical nuts born inside sticky green hulls that earned it the nickname lemon-nut (Rink, 1990). The nuts are a preferred food of squirrels and other wildlife. Butternuts were collected and eaten by Native Americans (Waugh, 1916; Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975) and early settlers, who also valued butternut for its workable, medium brown-colored wood (Kellogg, 1919), and as a source of medicine (Johnson, 1884), dyes (Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975), and sap sugar. Butternut’s native range extends over the entire north- eastern quarter of the United States, including many states immediately west of the Mississippi River, and into Canada. Butternut is more cold-tolerant than black walnut, and it grows as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and Figure 1.