A Brief Review of the Fossil History of the Family Rosaceae with a Focus On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 170 7th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Protection (ICEEP 2018) Effects of water stress on the growth status of five species of shrubs Pingwei Xiang1,a, Xiaoli Ma1,b, Xuefeng Liu1,c, Xiangcheng Yuan1,d, Zhihua Fu2,e* 1Chongqing three gorges academy of agricultural sciences, Wanzhou, Chongqing, China 2Chongqing Three Gorges Vocational College, Wanzhou, Chongqing,China [email protected],[email protected],[email protected], [email protected],[email protected] *Corresponding author. Pingwei Xiang and Xiaoli Ma contributed equally to this work. Keywords: Water stress; shrubs; leaf relative water content; leaf water retention Abstract: A pot experiments were conducted to study the effects of water stress on plant Blade retention, leaf relative moisture content (LRWC), Morphology and growth status, five drought-resistant plants (Pyracantha angustifolia, Pyracantha fortuneana, Pyracantha fortuneana ‘Harlequin’, Ligustrum japonicum ‘Howardii’, Photinia glabra×Photinia serrulata ) were used as materials. The results showed that the drought resistant ability of five species of shrubs from strong to weak as follows: Ligustrum japonicum 'Howardii',Pyracantha fortuneana , Pyracantha angustifolia,Photinia glabra×Photinia serrulata,Pyracantha fortuneana 'Harlequin'. It was found with several Comprehensive indicators that the drought tolerance of Ligustrum japonicum 'Howardii' was significantly higher than that of the other four species, and its adaptability to water deficit was stronger, -

Subalpine Meadows of Mount Rainier • an Elevational Zone Just Below Timberline but Above the Reach of More Or Less Continuous Tree Or Shrub Cover

Sub-Alpine/Alpine Zones and Flowers of Mt Rainier Lecturer: Cindy Luksus What We Are Going To Cover • Climate, Forest and Plant Communities of Mt Rainier • Common Flowers, Shrubs and Trees in Sub- Alpine and Alpine Zones by Family 1) Figwort Family 2) Saxifrage Family 3) Rose Family 4) Heath Family 5) Special mentions • Suggested Readings and Concluding Statements Climate of Mt Rainier • The location of the Park is on the west side of the Cascade Divide, but because it is so massive it produces its own rain shadow. • Most moisture is dropped on the south and west sides, while the northeast side can be comparatively dry. • Special microclimates result from unique interactions of landforms and weather patterns. • Knowing the amount of snow/rainfall and how the unique microclimates affect the vegetation will give you an idea of what will thrive in the area you visit. Forest and Plant Communities of Mt Rainier • The zones show regular patterns that result in “associations” of certain shrubs and herbs relating to the dominant, climax tree species. • The nature of the understory vegetation is largely determined by the amount of moisture available and the microclimates that exist. Forest Zones of Mt Rainier • Western Hemlock Zone – below 3,000 ft • Silver Fir Zone – between 2,500 and 4,700 ft • Mountain Hemlock Zone – above 4,000 ft Since most of the field trips will start above 4,000 ft we will only discuss plants found in the Mountain Hemlock Zone and above. This zone includes the Sub-Alpine and Alpine Plant communities. Forest and Plant Communities of Mt Rainier Subalpine Meadows of Mount Rainier • An elevational zone just below timberline but above the reach of more or less continuous tree or shrub cover. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

WRA Species Report

Family: Rosaceae Taxon: Pyracantha koidzumii Synonym: Cotoneaster koidzumii Hayata (basionym) Common Name Formosa firethorn tan wan huo ji Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Chuck Chimera Designation: H(HPWRA) Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Chuck Chimera WRA Score 7 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 y 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 n 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 405 Toxic to animals y=1, -

OSU Gardening with Oregon Native Plants

GARDENING WITH OREGON NATIVE PLANTS WEST OF THE CASCADES EC 1577 • Reprinted March 2008 CONTENTS Benefi ts of growing native plants .......................................................................................................................1 Plant selection ....................................................................................................................................................2 Establishment and care ......................................................................................................................................3 Plant combinations ............................................................................................................................................5 Resources ............................................................................................................................................................5 Recommended native plants for home gardens in western Oregon .................................................................8 Trees ...........................................................................................................................................................9 Shrubs ......................................................................................................................................................12 Groundcovers ...........................................................................................................................................19 Herbaceous perennials and ferns ............................................................................................................21 -

Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Multiple Chloroplast Regions: Implications to Genera Circumscription

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2018, Article ID 7627191, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7627191 Research Article Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Multiple Chloroplast Regions: Implications to Genera Circumscription Jiahui Sun ,1,2 Shuo Shi ,1,2,3 Jinlu Li,1,4 Jing Yu,1 Ling Wang,4 Xueying Yang,5 Ling Guo ,6 and Shiliang Zhou 1,2 1 State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China 2University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100043, China 3College of Life Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 4Te Department of Landscape Architecture, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China 5Key Laboratory of Forensic Genetics, Institute of Forensic Science, Ministry of Public Security, Beijing 100038, China 6Beijing Botanical Garden, Beijing 100093, China Correspondence should be addressed to Ling Guo; [email protected] and Shiliang Zhou; [email protected] Received 21 September 2017; Revised 11 December 2017; Accepted 2 January 2018; Published 19 March 2018 Academic Editor: Fengjie Sun Copyright © 2018 Jiahui Sun et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Maleae consists of economically and ecologically important plants. However, there are considerable disputes on generic circumscription due to the lack of a reliable phylogeny at generic level. In this study, molecular phylogeny of 35 generally accepted genera in Maleae is established using 15 chloroplast regions. Gillenia isthemostbasalcladeofMaleae,followedbyKageneckia + Lindleya, Vauquelinia, and a typical radiation clade, the core Maleae, suggesting that the proposal of four subtribes is reasonable. -

Devonian Plant Fossils a Window Into the Past

EPPC 2018 Sponsors Academic Partners PROGRAM & ABSTRACTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Scientific Committee: Zhe-kun Zhou Angelica Feurdean Jenny McElwain, Chair Tao Su Walter Finsinger Fraser Mitchell Lutz Kunzmann Graciela Gil Romera Paddy Orr Lisa Boucher Lyudmila Shumilovskikh Geoffrey Clayton Elizabeth Wheeler Walter Finsinger Matthew Parkes Evelyn Kustatscher Eniko Magyari Colin Kelleher Niall W. Paterson Konstantinos Panagiotopoulos Benjamin Bomfleur Benjamin Dietre Convenors: Matthew Pound Fabienne Marret-Davies Marco Vecoli Ulrich Salzmann Havandanda Ombashi Charles Wellman Wolfram M. Kürschner Jiri Kvacek Reed Wicander Heather Pardoe Ruth Stockey Hartmut Jäger Christopher Cleal Dieter Uhl Ellen Stolle Jiri Kvacek Maria Barbacka José Bienvenido Diez Ferrer Borja Cascales-Miñana Hans Kerp Friðgeir Grímsson José B. Diez Patricia Ryberg Christa-Charlotte Hofmann Xin Wang Dimitrios Velitzelos Reinhard Zetter Charilaos Yiotis Peta Hayes Jean Nicolas Haas Joseph D. White Fraser Mitchell Benjamin Dietre Jennifer C. McElwain Jenny McElwain Marie-José Gaillard Paul Kenrick Furong Li Christine Strullu-Derrien Graphic and Website Design: Ralph Fyfe Chris Berry Peter Lang Irina Delusina Margaret E. Collinson Tiiu Koff Andrew C. Scott Linnean Society Award Selection Panel: Elena Severova Barry Lomax Wuu Kuang Soh Carla J. Harper Phillip Jardine Eamon haughey Michael Krings Daniela Festi Amanda Porter Gar Rothwell Keith Bennett Kamila Kwasniewska Cindy V. Looy William Fletcher Claire M. Belcher Alistair Seddon Conference Organization: Jonathan P. Wilson -

Catalina Ironwood Lyonothamnus Floribundus Mature Specimen of B Y W a L T B U B E L I S Lyonothamnus Floribundus Ssp

HIDDEN TREASURE OF THE ARBORETUM Catalina Ironwood Lyonothamnus floribundus Mature specimen of B Y W ALT B U B ELIS Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp. asplenifolius growing in front of a Seattle home. (Photo by Walt Bubelis) anta Catalina Island lies some 26 miles off the California coast from Long Beach—a fact forever immortalized by the Four SPreps in their song “26 Miles”—and is where I E. Newton Street entrance to the Pinetum. It can first saw Lyonothamnus floribundus, while visiting take a while for young trees to put out flowers, so in 1976. if you want to see guaranteed blossoms this year, At the time, however, I didn’t give the plant its then the tall, narrow specimen at the Kruckeberg due, perhaps because I was distracted by all the garden is probably a better bet. other botanical wonders on the island. It wasn’t until some time later, when I saw a specimen at Two, Rare, Endemic Subspecies the Kruckeberg Botanic Garden, that I began to An unusual member of the rose family fully recognize its value as a garden tree. (Roseaceae), the genus Lyonothamnus is Highlights include gorgeous, glossy, evergreen monotypic, meaning that it only contains a foliage; stunning reddish-brown peeling bark; single species. Fossil records indicate a wider a narrow, columnar form (especially in its early distribution of the genus into Nevada and years); and myriad small, woolly, white flowers on Oregon (as well as possible other, now-extinct the branch tips from late spring to summer. species), however, today, Lyonothamnus The tree is still uncommon in the Puget Sound floribundus is restricted to the Channel Islands Region, but there are some notable specimens off the Southern California coast. -

Post-Wildfire Response of Shasta Snow-Wreath

California Fish and Wildlife, Fire Special Issue; 92-98; 2020 RESEARCH NOTE Post-wildfire response of Shasta snow-wreath LEN LINDSTRAND III1*, JULIE A. KIERSTEAD2, AND DEAN W. TAYLOR3 † 1Sierra Pacific Industries,P .O. Box 496014, Redding, CA 96049-6014, USA 2P. O. Box 491536, Redding CA, 96049, USA 33212 Redwood Drive, Aptos, CA, 95003, USA † Deceased *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Key words: Hirz fire, Neviusia cliftonii, post-wildfire response, Shasta snow-wreath, vegetative reproduction __________________________________________________________________________ Shasta snow-wreath (Neviusia cliftonii) is a rare shrub of the Rosaceae: tribe Kerrieae endemic to the southeastern Klamath Mountains in the general vicinity of Shasta Lake, Shasta County, California. The species was discovered less than 30 years ago (Shevock et al. 1992; Taylor 1993) and initially considered a limestone obligate. Subsequent occurrences have also been found on various non-limestone substrates (Lindstrand and Nelson 2005a, b, 2006; DeWoody et al. 2012; Jules et al. 2017). The only congener, Alabama snow-wreath (Neviusia alabamensis), also has a limited range restricted to several disjunct populations in the southeastern United States and occurs on limestone and non-limestone sedimentary substrates (Long 1989; Freiley 1994). Shasta snow-wreath is deciduous and produces flowers with showy white stamens, five toothed green sepals, and rarely, one to three narrow white petals. Based on our observations since its discovery, the species reproduces vegetatively, forming thickets of stems from the root system. Despite observations of developing achenes, no viable seed nor seedlings have been collected or observed. We are not aware of any pollinators and the blooms lack detect- able scent. -

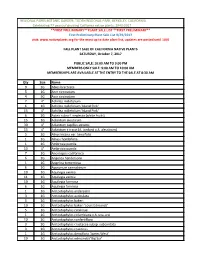

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Phylogenetic Inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) Using Chloroplast Ndhf and Nuclear Ribosomal ITS Sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 46 (3): 322–332 (2008) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.08050 (formerly Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica) http://www.plantsystematics.com Phylogenetic inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) using chloroplast ndhF and nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T. BERGGREN 3Chung-Hee LEE 4Stefanie ICKERT-BOND 5Ting-Shuang YI 6Ki-Oug YOO 7Lei XIE 8Joey SHAW 9Dan POTTER 1(Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 166, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA) 2(Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA) 3(Korean National Arboretum, 51-7 Jikdongni Soheur-eup Pocheon-si Gyeonggi-do, 487-821, Korea) 4(UA Museum of the North and Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6960, USA) 5(Key Laboratory of Plant Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650204, China) 6(Division of Life Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 200-701, Korea) 7(State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China) 8(Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, TN 37403-2598, USA) 9(Department of Plant Sciences, MS 2, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA) Abstract Sequences of the chloroplast ndhF gene and the nuclear ribosomal ITS regions are employed to recon- struct the phylogeny of Prunus (Rosaceae), and evaluate the classification schemes of this genus. The two data sets are congruent in that the genera Prunus s.l. and Maddenia form a monophyletic group, with Maddenia nested within Prunus.