Oemleria Cerasiformis (Torr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio Trees for Bees Denise Ellsworth, Department of Entomology

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES FACT SHEET ENT-71-15 Ohio Trees for Bees Denise Ellsworth, Department of Entomology Many people are concerned about the health and survival of bees, including honey bees, native bumble bees and the hundreds of lesser-known native and wild bees that call Ohio home. Bees are threatened by an assortment of factors such as pests, pathogens, pesticides, climate change and a lack of nesting habitat and forage plants. Bees and flowering plants have a critical relationship. Flowering plants provide nectar and pollen for a bee’s diet. Pollen is an essential source of protein for developing bee larvae, and nectar provides a carbohydrate source. Honey bees convert nectar into honey by adding an enzyme which breaks down the complex sugars into simple sugars. Bees, in turn, transport pollen from flower to flower as they forage, allowing for plant fertilization and the production of seeds and fruit. While trees provide many well-known ecological benefits, the importance of trees as a source of food for bees is sometimes overlooked. Ohio trees can provide food for bees from early spring through late summer, with most tree species in Ohio blooming in spring and early summer. This fact sheet describes some of the Ohio trees that provide food for bees. Trees included in this list have been described as important by multiple researchers and bee experts. Other trees not listed here can also provide food for bees. For example, Ohio horticultural experts have noted significant bee foraging activity on trees such as Carolina silverbell (Halesia carolina), seven-son flower (Heptacodium miconioides), goldenrain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata) and Japanese pagoda tree (Styphnolobium japonicum) in landscape settings. -

OSU Gardening with Oregon Native Plants

GARDENING WITH OREGON NATIVE PLANTS WEST OF THE CASCADES EC 1577 • Reprinted March 2008 CONTENTS Benefi ts of growing native plants .......................................................................................................................1 Plant selection ....................................................................................................................................................2 Establishment and care ......................................................................................................................................3 Plant combinations ............................................................................................................................................5 Resources ............................................................................................................................................................5 Recommended native plants for home gardens in western Oregon .................................................................8 Trees ...........................................................................................................................................................9 Shrubs ......................................................................................................................................................12 Groundcovers ...........................................................................................................................................19 Herbaceous perennials and ferns ............................................................................................................21 -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Phylogenetic Inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) Using Chloroplast Ndhf and Nuclear Ribosomal ITS Sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 46 (3): 322–332 (2008) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.08050 (formerly Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica) http://www.plantsystematics.com Phylogenetic inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) using chloroplast ndhF and nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T. BERGGREN 3Chung-Hee LEE 4Stefanie ICKERT-BOND 5Ting-Shuang YI 6Ki-Oug YOO 7Lei XIE 8Joey SHAW 9Dan POTTER 1(Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 166, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA) 2(Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA) 3(Korean National Arboretum, 51-7 Jikdongni Soheur-eup Pocheon-si Gyeonggi-do, 487-821, Korea) 4(UA Museum of the North and Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6960, USA) 5(Key Laboratory of Plant Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650204, China) 6(Division of Life Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 200-701, Korea) 7(State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China) 8(Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, TN 37403-2598, USA) 9(Department of Plant Sciences, MS 2, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA) Abstract Sequences of the chloroplast ndhF gene and the nuclear ribosomal ITS regions are employed to recon- struct the phylogeny of Prunus (Rosaceae), and evaluate the classification schemes of this genus. The two data sets are congruent in that the genera Prunus s.l. and Maddenia form a monophyletic group, with Maddenia nested within Prunus. -

Oxydendrum Arboreum Family: Ericaceae Sourwood

Oxydendrum arboreum Family: Ericaceae Sourwood The genus Oxydendrum contains only one species native to North America. The word oxydendrum comes from the Greek, meaning sour and tree, from the acid taste of the leaves. Oxydendrum arboreum- Arrowwood, Elk Tree, Lily of the Valley Tree, Sorrel Gum, Sorrel Tree, Sour Gum, Titi, Titi Tree Distribution From Pennsylvania to Ohio and Indiana, south to Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi and Louisiana, east to Florida, Georgia, Virginia and Maryland The Tree Sourwood is a medium size tree which grows at altitudes up to 3500 feet in well drained gravely soils. It grows scattered among Oaks, sweetgum, hickories and pines. It produces white flowers which are bell shaped like Lily of the Valley flowers and capsule shaped fruits. Sourwood attains a height of 60 feet and a diameter of 2 feet. The Wood General The sapwood of Sourwood is wide and yellowish brown to light pink brown, while the heartwood is brown tinged with red, dulling with age. It has no characteristic odor or taste and is heavy and hard. It is diffuse porous. Mechanical Properties (2-inch standard) Compression Specific MOE MOR Parallel Perpendicular WMLa Hardness Shear gravity GPa MPa MPa MPa kJ/m3 N MPa Green 0.50 9.1 53.1 22.4 4.69 68 3,247 8.0 Dry 0.55 10.6 80.0 42.7 7.45 75 4,181 10.3 WML = Work to maximum load. Reference (59). Drying and Shrinkage Percentage of shrinkage (green to final moisture content) Type of shrinkage 0% MC 6% MC 20% MC Tangential 8.9 – – Radial 6.3 – – Volumetric 15.2 – – Sourwood is difficult to season. -

Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections

Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections By Emily Beech, Kirsty Shaw and Meirion Jones June 2015 Recommended citation: Beech, E., Shaw, K., & Jones, M. 2015. Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections. BGCI. Acknowledgements BGCI gratefully acknowledges the many botanic gardens around the world that have contributed data to this survey (a full list of contributing gardens is provided in Annex 2). BGCI would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in the promotion of the survey and the collection of data, including the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Yorkshire Arboretum, University of Liverpool Ness Botanic Gardens, and Stone Lane Gardens & Arboretum (U.K.), and the Morton Arboretum (U.S.A). We would also like to thank contributors to The Red List of Betulaceae, which was a precursor to this ex situ survey. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) BGCI is a membership organization linking botanic gardens is over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. www.bgci.org FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) FFI, founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, based on sound science and take account of human needs. www.fauna-flora.org GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) GTC is undertaken through a partnership between BGCI and FFI, working with a wide range of other organisations around the world, to save the world’s most threated trees and the habitats which they grow through the provision of information, delivery of conservation action and support for sustainable use. -

Landscape Plants Rated by Deer Resistance

E271 Bulletin For a comprehensive list of our publications visit www.rce.rutgers.edu Landscape Plants Rated by Deer Resistance Pedro Perdomo, Morris County Agricultural Agent Peter Nitzsche, Morris County Agricultural Agent David Drake, Ph.D., Extension Specialist in Wildlife Management The following is a list of landscape plants rated according to their resistance to deer damage. The list was compiled with input from nursery and landscape professionals, Cooperative Extension personnel, and Master Gardeners in Northern N.J. Realizing that no plant is deer proof, plants in the Rarely Damaged, and Seldom Rarely Damaged categories would be best for landscapes prone to deer damage. Plants Occasionally Severely Damaged and Frequently Severely Damaged are often preferred by deer and should only be planted with additional protection such as the use of fencing, repellents, etc. Success of any of these plants in the landscape will depend on local deer populations and weather conditions. Latin Name Common Name Latin Name Common Name ANNUALS Petroselinum crispum Parsley Salvia Salvia Rarely Damaged Tagetes patula French Marigold Ageratum houstonianum Ageratum Tropaeolum majus Nasturtium Antirrhinum majus Snapdragon Verbena x hybrida Verbena Brugmansia sp. (Datura) Angel’s Trumpet Zinnia sp. Zinnia Calendula sp. Pot Marigold Catharanthus rosea Annual Vinca Occasionally Severely Damaged Centaurea cineraria Dusty Miller Begonia semperflorens Wax Begonia Cleome sp. Spider Flower Coleus sp. Coleus Consolida ambigua Larkspur Cosmos sp. Cosmos Euphorbia marginata Snow-on-the-Mountain Dahlia sp. Dahlia Helichrysum Strawflower Gerbera jamesonii Gerbera Daisy Heliotropium arborescens Heliotrope Helianthus sp. Sunflower Lobularia maritima Sweet Alyssum Impatiens balsamina Balsam, Touch-Me-Not Matricaria sp. False Camomile Impatiens walleriana Impatiens Myosotis sylvatica Forget-Me-Not Ipomea sp. -

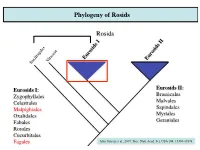

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

Honey Plant Chart

IMPORTANT NECTAR/POLLEN PRODUCING PLANTS IN MISSISSIPPI The following is a list of plants producing nectar and/or pollen for honey bees. Bloom dates for plants in northern Mississippi would be 2-4 weeks later than the same plants in North Mississippi depending on how far north they occur. Weather patterns may cause bloom times to vary as much as two weeks. The succession of blooming plants listed below should be correct in most cases. Some of the less important plants have been omitted. Those plants blooming in January, February and March are significant because they supply early nectar/pollen which is used for brood production and spring build-up; not necessarily for surplus honey. COMMON NAME Genus North Mississippi South Mississippi N = Nectar and/or Approximate Approximate P = Pollen species Bloom Date Bloom Date Hazel Alder/Tag Alder Alnus serrulata Late Jan. - Feb. Jan. 5 - Feb. 15 P Maple Acer rubrum Feb. 1 - Mar. 10 Jan. 25 - Feb. 15 N/P Henbit Lamium (2 sp.) Feb. 1 - Mar. 15 Jan. 20 - Mar. 1 N/P Wild Mustard Brassica kaber Mar. 10 - Mar. 30 Mar. 1 - Mar. 20 N/P Redbud Cercis canadensis Mar. 10 - Mar. 31 Feb. 15 - Mar. 15 N/P Elm Ulmus sp. Feb. 15 - Mar. 1 Jan. 15 - Feb. 5 P Spring Titi * Cliftonia Not Present Feb. 15 - April 10 N/P Black Titi monophylla Fruit Bloom Apple, Pear, etc. Mar. 1 - Mar. 30 Feb. 15 - Mar. 15 N/P Willow Salix sp. Mar. 25 - Apr. 10 Mar. 10 - Mar. 30 N/P Hawthorne Crataegus sp. -

Oxydendrum Arboreum.Indd

Oxydendrum arboreum (Sourwood) Heath Family (Ericaceae) Introduction: Truly a tree for all seasons, sourwood is one of our most beautiful natives and is ideal as a small specimen tree. It has lovely fl owers that open in mid-summer, excellent fall color, and hanging racemes of fruit capsules in the winter. Sourwood offers some of the best fall color among trees in the South, and has the best red of any of our natives. Fall color ranges from red to purple to yellow, and all three colors are often on the same tree. Culture: Sourwood is an exceptional tree for slightly acidic (pH 5.5-6.5), well-drained soils. It can be grown in full sun or partial shade although fl owering and fall color are best in full sun. The tree does reasonably well in dry, neutral soils. Sour- wood can be grown in Zones 5 (perhaps 4) to 9. This tree will not tolerate dry, compacted, alkaline soils or deicing salt, and is sensitive to root disturbance, so it is not ideal for urban areas. Sourwood has no serious pest problems. It should be trans- planted as a young, balled-and-burlapped or container-grown Botanical Characteristics: plant. Native habitat: Coast of Virginia to North Caro- lina and in southwestern Pennsylvania, southern Additional information: Ohio, Indiana, western Kentucky, Tennessee, the Sourwood’s bark is grayish brown tinged with red, and Appalachians to western Florida and the coasts of deeply furrowed with scaly ridges. In the wild, its bark often Mississippi and Louisiana. looks blocky like that of persimmon. -

IHCA Recommended Plant List

Residential Architectural Review Committee Recommended Plant List Plant Materials The following plant materials are intended to guide tree and shrub ADDITIONS to residential landscapes at Issaquah Highlands. Lot sizes, shade, wind and other factors place size and growth constraints on plants, especially trees, which are suitable for addition to existing landscapes. Other plant materials may be considered that have these characteristics and similar maintenance requirements. Additional species and varieties may be selected if authorized by the Issaquah Highlands Architectural Review Committee. This list is not exhaustive but does cover most of the “good doers” for Issaquah Highlands. Our microclimate is colder and harsher than those closer to Puget Sound. Plants not listed should be used with caution if their performance has not been observed at Issaquah Highlands. * Drought-tolerant plant ** Requires well-drained soil DECIDUOUS TREES: Small • Acer circinatum – Vine Maple • Acer griseum – Paperbark Maple • *Acer ginnala – Amur Maple • Oxydendrum arboreum – Sourwood • Acer palmation – Japanese Maple • *Prunus cerasifera var. – Purple Leaf Plum varieties • Amelanchier var. – Serviceberry varieties • Styrax japonicus – Japanese Snowbell • Cornus species, esp. kousa Medium • Acer rufinerve – Redvein Maple • Cornus florida (flowering dogwood) • *Acer pseudoplatanus – Sycamore Maple • Acer palmatum (Japanese maple, many) • • *Carpinus betulus – European Hornbeam Stewartia species (several) • *Parrotia persica – Persian Parrotia Columnar Narrow -

The Role of the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden

Research article The role of the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden (Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico) in the conservation of the Mexican flora El papel del Jardín Botánico Francisco Javier Clavijero (Xalapa, Veracruz, México) en la conservación de la flora mexicana Milton H. Díaz-Toribio1,3 , Victor Luna1 , Andrew P. Vovides2 Abstract: Background and Aims: There are approximately 3000 botanic gardens in the world. These institutions cultivate approximately six million plant species, representing around 100,000 taxa in cultivation. Botanic gardens make an important contributionex to situ conservation with a high number of threat- ened plant species represented in their collections. To show how the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden (JBC) contributes to the conservation of Mexican flora, we asked the following questions: 1) How is vascular plant diversity currently conserved in the JBC?, 2) How well is this garden perform- ing with respect to the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) and the Mexican Strategy for Plant Conservation (MSPC)?, and 3) How has the garden’s scientific collection contributed to the creation of new knowledge (description of new plant species)? Methods: We used data from the JBC scientific living collection stored in BG-BASE. We gathered information on species names, endemism, and endan- gered status, according to national and international policies, and field data associated with each species. Key results: We found that 12% of the species in the JBC collection is under some risk category by international and Mexican laws. Plant families with the highest numbers of threatened species were Zamiaceae, Orchidaceae, Arecaceae, and Asparagaceae. We also found that Ostrya mexicana, Tapirira mexicana, Oreopanax capitatus, O.