School Library Standards in Support of YA Urban Literature's Transformative Impacts on Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fan Cultures Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FAN CULTURES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matthew Hills | 256 pages | 01 Mar 2002 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415240253 | English | London, United Kingdom Fan Cultures PDF Book In America, the fandom also began as an offshoot of science fiction fandom, with fans bringing imported copies of Japanese manga to conventions. Rather than submitting a work of fan fiction to a zine where, if accepted, it would be photocopied along with other works and sent out to a mailing list, modern fans can post their works online. Those who fall victim to the irrational appeals are manipulated by mass media to essentially display irrational loyalties to an aspect of pop culture. Harris, Cheryl, and Alison Alexander. She addresses her interests in American cultural and social thought through her works. In doing so, they create spaces where they can critique prescriptive ideas of gender, sexuality, and other norms promoted in part by the media industry. Stanfill, Mel. Cresskill, N. In his first book Fan Cultures , Hills outlines a number of contradictions inherent in fan communities such as the necessity for and resistance towards consumerism, the complicated factors associated with hierarchy, and the search for authenticity among several different types of fandom. Therefore, fans must perpetually occupy a space in which they carve out their own unique identity, separate from conventional consumerism but also bolster their credibility with particular collectors items. They rose to stardom separately on their own merits -- Pickford with her beauty, tumbling curls, and winning combination of feisty determination and girlish sweetness, and Fairbanks with his glowing optimism and athletic stunts. Gifs or gif sets can be used to create non-canon scenarios mixing actual content or adding in related content. -

Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin

Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Volume 6, No. 6: October, 1996 Southern Fandom Confederation Contents Ad Rates The Carpetbagger..................................................................... 1 Type Full-Page Half-Page 1/4 Page Another Con Report................................................................4 Fan $25.00 $12.50 $7.25 Treasurer's Report................................................................... 5 Mad Dog's Southern Convention Listing............................. 6 Pro $50.00 $25.00 $12.50 Southern Fanzines................................................................... 8 Southern Fandom on the Web................................................9 Addresses Southern Clubs...................................................................... 10 Letters..................................................................................... 13 Physical Mail: SFC/DSC By-laws...................................................... 20 President Tom Feller, Box 13626,Jackson, MS 39236-3626 Cover Artist........................................................John Martello Vice-President Bill Francis, P.O. Box 1271, Policies Brunswick, GA 31521 The Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Secretary-Treasurer Judy Bemis, 1405 (SFCB) Vol. 6, No. 6, October, 1996, is the official Waterwinds CT,Wake Forest, NC 27587 publication of the Southern Fandom Confederation (SFC), a not-for-profit literary organization and J. R. Madden, 7515 Shermgham Avenue, Baton information clearinghouse dedicated to the service of Rouge, LA 70808-5762 -

A Fans' Notes, Frederick Exley Describes the Ritualized Viewing

Contact Sport Robert Cavanagh Over the last twenty-five years, fantasy sports have become an increasingly prominent form of popular culture. During this same period, fan studies have also become an important strain of media and cultural studies. In what follows, I will consider the relationship between these two phenomena and demonstrate how each can help us rethink the other. In fantasy competitions sports fans assemble imaginary teams of professional athletes that may or may not play on the same “real-life” team and play these teams against others in imaginary leagues. Scoring is based on the statistically quantified real-life performances of an individual “owner’s” team of players. In fantasy sports, in other words, the competition is between fans. As I will argue, the competitive logic and culture of fantasy sports embody much of what fan studies has articulated about both the active, participatory nature of fandom and also the increased sensitivity of contemporary culture industries to it. But I will also show how fantasy participation and the incorporation of fantasy fandom by pre-existing forms of spectacle raise fundamental questions about our investment in worlds defined by their separation from reality, and that fan studies must also confront these questions. In order to articulate the relation between fantasy and participation that I want to explore, I will focus on a particular variety of fantasy sports—fantasy football—and a book that deals extensively with the connection between football and fantasy: Frederick Exley’s “fictional memoir” A Fans’ Notes. A Fan’s Notes was first published in 1968, one year after the first documented fantasy football league was founded.1 Exley’s representation of football fandom does not imagine the kind of participatory culture that would emerge around fantasy sports. -

Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy Kimberly Wickham University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Wickham, Kimberly, "Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 716. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/716 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUESTING FEMINISM: NARRATIVE TENSIONS AND MAGICAL WOMEN IN MODERN FANTASY BY KIMBERLY WICKHAM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF KIMBERLY WICKHAM APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Carolyn Betensky Robert Widell Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 Abstract Works of Epic Fantasy often have the reputation of being formulaic, conservative works that simply replicate the same tired story lines and characters over and over. This assumption prevents Epic Fantasy works from achieving wide critical acceptance resulting in an under-analyzed and under-appreciated genre of literature. While some early works do follow the same narrative path as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Epic Fantasy has long challenged and reworked these narratives and character tropes. That many works of Epic Fantasy choose replicate the patriarchal structures found in our world is disappointing, but it is not an inherent feature of the genre. -

SF/SF #136! 1!February 2013 Editorial

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 137 Editor-in-Chief: Jean Martin January 30, 2013 Managing Editor: Christopher Erickson email: [email protected] Editor: España Sheriff Compositor: Tom Becker Contents Editorial ......................................................................................Jean Martin............................. ........................................................................................ 2 Upcoming Year of Geekitude ....................................................Christopher Erickson.............. ........................................................................................ 6 The Fur From Outer Space....................................................... Christopher Erickson.............. Photos by Christopher Erickson................................... 10 HMS Pinafore: The Next Generation ......................................Tom Becker ............................Photos by Tom Becker .................................................16 The Books of the Raksura by Martha Wells ...........................Tom Becker .................................................................................................................. 22 Letters of Comment ...................................................................Jean Martin............................. ...................................................................................... 25 BASFA Meetings 1169-74 ..........................................................BASFA ........................................................................................................................ -

Elfe Complet Streaming Francais

[2KHD-1080p] Elfe Complet Streaming Francais [2KHD-1080p] Elfe Complet Streaming Francais [complet HD 1080p] Elfe (2003) Film Complet En Français Gratuit Película de Detalles: Titre: Elfe Date de sortie: 2003-10-09 Durée: 97 Minutes Genre: Comédie, Familial, Fantastique langue: Français Elfe — Wikipédia ~ Un elfe est une créature légendaire anthropomorphe dont lapparence le rôle et la symbolique peuvent être très divers À lorigine il sagissait dêtres de la mythologie nordique dont le souvenir dure toujours dans le folklore scandinave Les elfes étaient originellement des divinités mineures de la nature et de la fertilité ELFE ~ Elfe est la première étude scientifique d’envergure nationale consacrée au suivi des enfants de la naissance à l’âge adulte qui aborde les multiples aspects de leur vie sous l’angle des sciences sociales de la santé et de l’environnement Grâce au suivi régulier des enfants elle permettra de mieux comprendre comment l’environnement l’entourage familial le milieu scolaire ou encore les conditions de vie des enfants peuvent influencer leur développement leur santé file:///D/MOVIEFR/elfe-complet-streaming-francais.html[10/16/2020 11:01:45 PM] [2KHD-1080p] Elfe Complet Streaming Francais ELFE Définition de ELFE ~ ELFE subst masc MYTH Esprit de taille infime mais dune puissance redoutable symbolisant les forces de lair du feu tantôt vivant dans lair et bienfaisants tantôt vivant au centre de la terre et malveillants elfe — Wiktionnaire ~ Fantastique Créature féerique ressemblant à un être humain mince souvent représenté -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Crafting Women’s Narratives The Material Impact of Twenty-First Century Romance Fiction on Contemporary Steampunk Dress Shannon Marie Rollins A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Art) at The University of Edinburgh Edinburgh College of Art, School of Art September 2019 Rollins i ABSTRACT Science fiction author K.W. Jeter coined the term ‘steampunk’ in his 1987 letter to the editor of Locus magazine, using it to encompass the burgeoning literary trend of madcap ‘gonzo’-historical Victorian adventure novels. Since this watershed moment, steampunk has outgrown its original context to become a multimedia field of production including art, fashion, Do-It-Yourself projects, role-playing games, film, case-modified technology, convention culture, and cosplay alongside science fiction. And as steampunk creativity diversifies, the link between its material cultures and fiction becomes more nuanced; where the subculture began as an extension of the text in the 1990s, now it is the culture that redefines the fiction. -

Petition for Cancelation

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA743501 Filing date: 04/30/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Petition for Cancellation Notice is hereby given that the following party requests to cancel indicated registration. Petitioner Information Name Organization for Transformative Works, Inc. Entity Corporation Citizenship Delaware Address 2576 Broadway #119 New York City, NY 10025 UNITED STATES Correspondence Heidi Tandy information Legal Committee Member Organization for Transformative Works, Inc. 1691 Michigan Ave Suite 360 Miami Beach, FL 33139 UNITED STATES [email protected] Phone:3059262227 Registration Subject to Cancellation Registration No 4863676 Registration date 12/01/2015 Registrant Power I Productions LLC 163 West 18th Street #1B New York, NY 10011 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Subject to Cancellation Class 041. First Use: 2013/12/01 First Use In Commerce: 2015/08/01 All goods and services in the class are cancelled, namely: Entertainment services, namely, an ongo- ing series featuring documentary films featuring modern cultural phenomena provided through the in- ternet and movie theaters; Entertainment services, namely, displaying a series of films; Entertain- mentservices, namely, providing a web site featuring photographic and prose presentations featuring modern cultural phenomena; Entertainment services, namely, storytelling Grounds for Cancellation The mark is merely descriptive Trademark Act Sections 14(1) and 2(e)(1) The mark is or has become generic Trademark Act Section 14(3), or Section 23 if on Supplemental Register Attachments Fandom_Generic_Petition.pdf(2202166 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 1.pdf(4769247 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 2.pdf(4885778 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 3.pdf(3243682 bytes ) Certificate of Service The undersigned hereby certifies that a copy of this paper has been served upon all parties, at their address record by First Class Mail on this date. -

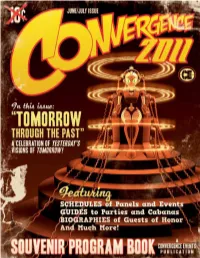

Souvenir & Program Book (PDF)

THAT STATEMENT CONNECTS the modern Steam Punk Movement, The Jetsons, Metropolis, Disney's Tomorrowland, and the other items that we are celebrating this weekend. Some of those past futures were unpleasant: the Days of Future Past of the X-Men are a shadow of a future that the adult Kate Pryde wanted to avoid when she went back to the present day of the early 1980s. Others set goals and dreams; the original Star Trek gave us the dreams and goals of a bright and shiny future t h a t h a v e i n s p i r e d generations of scientists and engineers. Robert Heinlein took us to the Past through Tomorrow in his Future History series, and Asimov's Foundation built planet-wide cities and we collect these elements of the past for the future. We love the fashion of the Steampunk movement; and every year someone is still asking for their long-promised jet pack. We take the ancient myths of the past and reinterpret them for the present and the future, both proving and making them still relevant today. Science Fiction and Fantasy fandom is both nostalgic and forward-looking, and the whole contradictory nature is in this year's theme. Many of the years that previous generations of writers looked forward to happened years ago; 1984, 1999, 2001, even 2010. The assumptions of those time periods are perhaps out-of-date; technology and society have passed those stories by, but there are elements that still speak to us today. It is said that the Golden Age of Science Fiction is when you are 13. -

Thesis the Communication of Fan Culture: the Impact of New Media on Science Fiction and Fantasy Fandom Georgia Institute of Tech

Thesis The Communication of Fan Culture: The Impact of New Media on Science Fiction and Fantasy Fandom Georgia Institute of Technology Author ………………………………………………………………………. Betsy Gooch Science, Technology, and Culture School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Advisor ………………………………………………………………….…… Lisa Yaszek Associate Professor Science, Technology, and Culture Program School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Certified by ……………………………………………………………………. Carol Senf Associate Chair Science, Technology, and Culture Program Coordinator School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Abstract Historically, fan culture has played an enormous role in the creation and development of science fiction and fantasy, and the genres have left a significant impact on the lives of their fans. I have determined that fandom relies on and can be described purely by its method of communication. This essay traces the historical relevance of the fan community as it relates to the evolution of science fiction and fantasy and the contributions fans have made to the genre’s literary and stylistic conventions. This paper will also be showcasing the genres’ influence on its fans’ lives, such as through the establishment of fan culture, as well as the reasons this highly interconnected relationship is necessary to the continued existence of the science fiction and fantasy genres. Particularly, this paper highlights the key activities and productions of fan culture: the languages (fanspeak), dress codes (costuming), literature (fan fiction), art (fan art), and music (filking), and the organized outlets for fan activities (conventions and fanzines). Each of these activities and productions is a mode of communication, and it is this communication between fans that creates fan community and culture. These activities and productions will be explained in an anthropological manner that will explore the cultural reasoning for and issues that occur due to these fan activities. -

Fancyclopedia 1 Bristol-Speer 1944

„ . '- , >■ £ • • FANCYCLOPEDIAi . "• ■' ' ■ <■ ■' ' . • ■ ■ . JOHN BRISTOL •, r-‘ FF LASFS Published by Forrest J Ackerman 1 \ . *r» LIMITED EDITION 250 COPIES COPY NO 0 PREPARED FOR The purpose of the Jb.ncyclopedia, not fully realized, is to define all expres sions, except nonce-words, which have an esoteric meaning in fantasy fandom, and to supply other information, such as that on Esperanto, which may he needed to understand what fans say, write, and do. It should ho remarked, however, that fans mako many allusions to material in prozines, fanzines, and other places, which no reference work could cover completely. Certain fields havo been ex cluded from the scope of the Eancyclopedia "because they are well taken care of elsewhere. While nicknames of fans and pet names of fan magazines are identified hero, biographies have heen left to the various ‘Who's Whos of fandom, and fan zines in detail to Dr Swisher's excellent S-F Check-List. Despite our efforts for accuracy and completeness, many errors and omissions will no douht he discovered heroin. The editor will appreciate receiving corrective information. It is sug gested that those who have little or no acquaintance with fantasy or fan activity read the articles on those subjects first, then look up, in the normal alphabeti cal place, expressions not understood which have been used in those two articles. It has seomed more efficient for the probable uses of this handbook, and economi cal of space, to give short articles on many subjects rather than long articles on a few broad subjects. To find a desired subject, look first under the word that you have in mind. -

Participatory Culture: a Study on Bangtan Boys Fandom Indonesia

KOMUNIKA: Jurnal Dakwah dan Komunikasi Vol. 13, No. 2, Oktober 2019 http://ejournal.iainpurwokerto.ac.id/index.php/komunika Participatory Culture: A Study on Bangtan Boys Fandom Indonesia Cendera Rizky Bangun Article Information Fakultas Ilmu Komunikasi, Submitted March 21, 2019 Universitas Multimedia Nusantara, Tangerang Revision April 30, 2019 Email Korespondensi: [email protected] Accepted May 9, 2019 Published October 1, 2019 Abstract In the past few years, South Korean pop culture has become a global phenomenon. The sudden popularity of the culture commonly known as as Korean Wave or Hallyu. This trend includes Korean drama, dance, music, films, animation, games, and fans club for Korean pop celebrity. In the past, those who become fans is only from a spesific age, but now it is more varied. One of most popular of the Korean singer groups is BangTan Boys. Abbreviated as BTS, the fans of BangTan Boys is proudly call themselves, “ARMY”. Using the Henry Jenkins’s Participatory culture theory along with qualitative method, this research tries to analyze that there are audiens who do not only consuming pop culture, but also producing new cultural artefacts from that. The data were collected by focus group discussion, in-depth interview and data analysis. It shows that some of the fans are making “fanfiction” as the reproductions of new artefacts, despite actively participating in BTS fandom by doing activities as include in the four types of Jenkin’s participatory cultures. Keywords: Cultural Studies, Fandom, Participatory Culture, Korean Pop, BTS Introduction As a global phenomenon, Korean Pop Culture has flourished causing what so called the Korean Wave impact.