The Arithmetic of Cardinal Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set Theory, by Thomas Jech, Academic Press, New York, 1978, Xii + 621 Pp., '$53.00

BOOK REVIEWS 775 BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 3, Number 1, July 1980 © 1980 American Mathematical Society 0002-9904/80/0000-0 319/$01.75 Set theory, by Thomas Jech, Academic Press, New York, 1978, xii + 621 pp., '$53.00. "General set theory is pretty trivial stuff really" (Halmos; see [H, p. vi]). At least, with the hindsight afforded by Cantor, Zermelo, and others, it is pretty trivial to do the following. First, write down a list of axioms about sets and membership, enunciating some "obviously true" set-theoretic principles; the most popular Hst today is called ZFC (the Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms with the axiom of Choice). Next, explain how, from ZFC, one may derive all of conventional mathematics, including the general theory of transfinite cardi nals and ordinals. This "trivial" part of set theory is well covered in standard texts, such as [E] or [H]. Jech's book is an introduction to the "nontrivial" part. Now, nontrivial set theory may be roughly divided into two general areas. The first area, classical set theory, is a direct outgrowth of Cantor's work. Cantor set down the basic properties of cardinal numbers. In particular, he showed that if K is a cardinal number, then 2", or exp(/c), is a cardinal strictly larger than K (if A is a set of size K, 2* is the cardinality of the family of all subsets of A). Now starting with a cardinal K, we may form larger cardinals exp(ic), exp2(ic) = exp(exp(fc)), exp3(ic) = exp(exp2(ic)), and in fact this may be continued through the transfinite to form expa(»c) for every ordinal number a. -

Mathematics 144 Set Theory Fall 2012 Version

MATHEMATICS 144 SET THEORY FALL 2012 VERSION Table of Contents I. General considerations.……………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 1. Overview of the course…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 2. Historical background and motivation………………………………………………………….………………4 3. Selected problems………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 I I. Basic concepts. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 1. Topics from logic…………………………………………………………………………………………………………16 2. Notation and first steps………………………………………………………………………………………………26 3. Simple examples…………………………………………………………………………………………………………30 I I I. Constructions in set theory.………………………………………………………………………………..……….34 1. Boolean algebra operations.……………………………………………………………………………………….34 2. Ordered pairs and Cartesian products……………………………………………………………………… ….40 3. Larger constructions………………………………………………………………………………………………..….42 4. A convenient assumption………………………………………………………………………………………… ….45 I V. Relations and functions ……………………………………………………………………………………………….49 1.Binary relations………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ….49 2. Partial and linear orderings……………………………..………………………………………………… ………… 56 3. Functions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ….…….. 61 4. Composite and inverse function.…………………………………………………………………………… …….. 70 5. Constructions involving functions ………………………………………………………………………… ……… 77 6. Order types……………………………………………………………………………………………………… …………… 80 i V. Number systems and set theory …………………………………………………………………………………. 84 1. The Natural Numbers and Integers…………………………………………………………………………….83 2. Finite induction -

Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of Abbreviations

Notes: c F.P. Greenleaf, 2000-2014 v43-s14sets.tex (version 1/1/2014) Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of abbreviations. Below we list some standard math symbols that will be used as shorthand abbreviations throughout this course. means “for all; for every” • ∀ means “there exists (at least one)” • ∃ ! means “there exists exactly one” • ∃ s.t. means “such that” • = means “implies” • ⇒ means “if and only if” • ⇐⇒ x A means “the point x belongs to a set A;” x / A means “x is not in A” • ∈ ∈ N denotes the set of natural numbers (counting numbers) 1, 2, 3, • · · · Z denotes the set of all integers (positive, negative or zero) • Q denotes the set of rational numbers • R denotes the set of real numbers • C denotes the set of complex numbers • x A : P (x) If A is a set, this denotes the subset of elements x in A such that •statement { ∈ P (x)} is true. As examples of the last notation for specifying subsets: x R : x2 +1 2 = ( , 1] [1, ) { ∈ ≥ } −∞ − ∪ ∞ x R : x2 +1=0 = { ∈ } ∅ z C : z2 +1=0 = +i, i where i = √ 1 { ∈ } { − } − 1.2 Basic facts from set theory. Next we review the basic definitions and notations of set theory, which will be used throughout our discussions of algebra. denotes the empty set, the set with nothing in it • ∅ x A means that the point x belongs to a set A, or that x is an element of A. • ∈ A B means A is a subset of B – i.e. -

641 1. P. Erdös and A. H. Stone, Some Remarks on Almost Periodic

1946] DENSITY CHARACTERS 641 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. P. Erdös and A. H. Stone, Some remarks on almost periodic transformations, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. vol. 51 (1945) pp. 126-130. 2. W. H. Gottschalk, Powers of homeomorphisms with almost periodic propertiesf Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. vol. 50 (1944) pp. 222-227. UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA AND UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA A REMARK ON DENSITY CHARACTERS EDWIN HEWITT1 Let X be an arbitrary topological space satisfying the TVseparation axiom [l, Chap. 1, §4, p. 58].2 We recall the following definition [3, p. 329]. DEFINITION 1. The least cardinal number of a dense subset of the space X is said to be the density character of X. It is denoted by the symbol %{X). We denote the cardinal number of a set A by | A |. Pospisil has pointed out [4] that if X is a Hausdorff space, then (1) |X| g 22SW. This inequality is easily established. Let D be a dense subset of the Hausdorff space X such that \D\ =S(-X'). For an arbitrary point pÇ^X and an arbitrary complete neighborhood system Vp at p, let Vp be the family of all sets UC\D, where U^VP. Thus to every point of X, a certain family of subsets of D is assigned. Since X is a Haus dorff space, VpT^Vq whenever p j*£q, and the correspondence assigning each point p to the family <DP is one-to-one. Since X is in one-to-one correspondence with a sub-hierarchy of the hierarchy of all families of subsets of D, the inequality (1) follows. -

MATH 361 Homework 9

MATH 361 Homework 9 Royden 3.3.9 First, we show that for any subset E of the real numbers, Ec + y = (E + y)c (translating the complement is equivalent to the complement of the translated set). Without loss of generality, assume E can be written as c an open interval (e1; e2), so that E + y is represented by the set fxjx 2 (−∞; e1 + y) [ (e2 + y; +1)g. This c is equal to the set fxjx2 = (e1 + y; e2 + y)g, which is equivalent to the set (E + y) . Second, Let B = A − y. From Homework 8, we know that outer measure is invariant under translations. Using this along with the fact that E is measurable: m∗(A) = m∗(B) = m∗(B \ E) + m∗(B \ Ec) = m∗((B \ E) + y) + m∗((B \ Ec) + y) = m∗(((A − y) \ E) + y) + m∗(((A − y) \ Ec) + y) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (Ec + y)) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (E + y)c) The last line follows from Ec + y = (E + y)c. Royden 3.3.10 First, since E1;E2 2 M and M is a σ-algebra, E1 [ E2;E1 \ E2 2 M. By the measurability of E1 and E2: ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E1) = m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E2) = m (E2 \ E1) + m (E2 \ E1) ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c m (E1) + m (E2) = 2m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c = m (E1 \ E2) + [m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2)] c c Second, E1 \ E2, E1 \ E2, and E1 \ E2 are disjoint sets whose union is equal to E1 [ E2. -

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55B

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55b 1. Give an example of a subset A ⊂ R such that, by repeatedly taking closures and complements. Take A := (−5; −4)−Q [[−4; −3][f2g[[−1; 0][(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ (4; 5)\Q . (The number of intervals in this sets is unnecessarily large, but, as Kevin suggested, taking a set that is complement-symmetric about 0 cuts down the verification in half. Note that this set is the union of f0g[(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ ([4; 5] \ Q) and the complement of the reflection of this set about the the origin). Because of this symmetry, we only need to verify that the closure- complement-closure sequence of the set f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q consists of seven distinct sets. Here are the (first) seven members of this sequence; from the eighth member the sets start repeating period- ically: f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q ; f0g [ [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 0) [ (0; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1); (−∞; 1] [ [3; 4] [ [5; 1); (1; 3) [ (4; 5); [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1). Thus, by symmetry, both the closure- complement-closure and complement-closure-complement sequences of A consist of seven distinct sets, and hence there is a total of 14 different sets obtained from A by taking closures and complements. Remark. That 14 is the maximal possible number of sets obtainable for any metric space is the Kuratowski complement-closure problem. This is proved by noting that, denoting respectively the closure and com- plement operators by a and b and by e the identity operator, the relations a2 = a; b2 = e, and aba = abababa take place, and then one can simply list all 14 elements of the monoid ha; b j a2 = a; b2 = e; aba = abababai. -

ON the CONSTRUCTION of NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES from EXISTING ONES Consider a Function F

ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES FROM EXISTING ONES EMILY RIEHL Abstract. In this note, we introduce a guiding principle to define topologies for a wide variety of spaces built from existing topological spaces. The topolo- gies so-constructed will have a universal property taking one of two forms. If the topology is the coarsest so that a certain condition holds, we will give an elementary characterization of all continuous functions taking values in this new space. Alternatively, if the topology is the finest so that a certain condi- tion holds, we will characterize all continuous functions whose domain is the new space. Consider a function f : X ! Y between a pair of sets. If Y is a topological space, we could define a topology on X by asking that it is the coarsest topology so that f is continuous. (The finest topology making f continuous is the discrete topology.) Explicitly, a subbasis of open sets of X is given by the preimages of open sets of Y . With this definition, a function W ! X, where W is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function W ! Y is continuous. On the other hand, if X is assumed to be a topological space, we could define a topology on Y by asking that it is the finest topology so that f is continuous. (The coarsest topology making f continuous is the indiscrete topology.) Explicitly, a subset of Y is open if and only if its preimage in X is open. With this definition, a function Y ! Z, where Z is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function X ! Z is continuous. -

MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED from PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES §1. Introduction. a Family a of Infinite Subsets of Ω Is Called

The Journal of Symbolic Logic Volume 00, Number 0, XXX 0000 MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED FROM PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES JORG¨ BRENDLE AND YURII KHOMSKII 1 Abstract. We prove the consistency of b > @1 together with the existence of a Π1- definable mad family, answering a question posed by Friedman and Zdomskyy in [7, Ques- tion 16]. For the proof we construct a mad family in L which is an @1-union of perfect a.d. sets, such that this union remains mad in the iterated Hechler extension. The construction also leads us to isolate a new cardinal invariant, the Borel almost-disjointness number aB , defined as the least number of Borel a.d. sets whose union is a mad family. Our proof yields the consistency of aB < b (and hence, aB < a). x1. Introduction. A family A of infinite subsets of ! is called almost disjoint (a.d.) if any two elements a; b of A have finite intersection. A family A is called maximal almost disjoint, or mad, if it is an infinite a.d. family which is maximal with respect to that property|in other words, 8a 9b 2 A (ja \ bj = !). The starting point of this paper is the following theorem of Adrian Mathias [11, Corollary 4.7]: Theorem 1.1 (Mathias). There are no analytic mad families. 1 On the other hand, it is easy to see that in L there is a Σ2 definable mad family. In [12, Theorem 8.23], Arnold Miller used a sophisticated method to 1 prove the seemingly stronger result that in L there is a Π1 definable mad family. -

Cardinality of Wellordered Disjoint Unions of Quotients of Smooth Equivalence Relations on R with All Classes Countable Is the Main Result of the Paper

CARDINALITY OF WELLORDERED DISJOINT UNIONS OF QUOTIENTS OF SMOOTH EQUIVALENCE RELATIONS WILLIAM CHAN AND STEPHEN JACKSON Abstract. Assume ZF + AD+ + V = L(P(R)). Let ≈ denote the relation of being in bijection. Let κ ∈ ON and hEα : α<κi be a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes countable and for all α<κ, R R R R R /Eα ≈ . Then the disjoint union Fα<κ /Eα is in bijection with × κ and Fα<κ /Eα has the J´onsson property. + <ω Assume ZF + AD + V = L(P(R)). A set X ⊆ [ω1] 1 has a sequence hEα : α<ω1i of equivalence relations on R such that R/Eα ≈ R and X ≈ F R/Eα if and only if R ⊔ ω1 injects into X. α<ω1 ω ω Assume AD. Suppose R ⊆ [ω1] × R is a relation such that for all f ∈ [ω1] , Rf = {x ∈ R : R(f,x)} ω is nonempty and countable. Then there is an uncountable X ⊆ ω1 and function Φ : [X] → R which uniformizes R on [X]ω: that is, for all f ∈ [X]ω, R(f, Φ(f)). Under AD, if κ is an ordinal and hEα : α<κi is a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes ω R countable, then [ω1] does not inject into Fα<κ /Eα. 1. Introduction The original motivation for this work comes from the study of a simple combinatorial property of sets using only definable methods. The combinatorial property of concern is the J´onsson property: Let X be any n n <ω n set. -

Cardinal Invariants Concerning Functions Whose Sum Is Almost Continuous Krzysztof Ciesielski West Virginia University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Faculty Scholarship 1995 Cardinal Invariants Concerning Functions Whose Sum Is Almost Continuous Krzysztof Ciesielski West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Mathematics Commons Digital Commons Citation Ciesielski, Krzysztof, "Cardinal Invariants Concerning Functions Whose Sum Is Almost Continuous" (1995). Faculty Scholarship. 822. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications/822 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cardinal invariants concerning functions whose sum is almost continuous. Krzysztof Ciesielski1, Department of Mathematics, West Virginia University, Mor- gantown, WV 26506-6310 ([email protected]) Arnold W. Miller1, York University, Department of Mathematics, North York, Ontario M3J 1P3, Canada, Permanent address: University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Mathematics, Van Vleck Hall, 480 Lincoln Drive, Madison, Wis- consin 53706-1388, USA ([email protected]) Abstract Let A stand for the class of all almost continuous functions from R to R and let A(A) be the smallest cardinality of a family F ⊆ RR for which there is no g: R → R with the property that f + g ∈ A for all f ∈ F . We define cardinal number A(D) for the class D of all real functions with the Darboux property similarly. -

Elements of Set Theory

Elements of set theory April 1, 2014 ii Contents 1 Zermelo{Fraenkel axiomatization 1 1.1 Historical context . 1 1.2 The language of the theory . 3 1.3 The most basic axioms . 4 1.4 Axiom of Infinity . 4 1.5 Axiom schema of Comprehension . 5 1.6 Functions . 6 1.7 Axiom of Choice . 7 1.8 Axiom schema of Replacement . 9 1.9 Axiom of Regularity . 9 2 Basic notions 11 2.1 Transitive sets . 11 2.2 Von Neumann's natural numbers . 11 2.3 Finite and infinite sets . 15 2.4 Cardinality . 17 2.5 Countable and uncountable sets . 19 3 Ordinals 21 3.1 Basic definitions . 21 3.2 Transfinite induction and recursion . 25 3.3 Applications with choice . 26 3.4 Applications without choice . 29 3.5 Cardinal numbers . 31 4 Descriptive set theory 35 4.1 Rational and real numbers . 35 4.2 Topological spaces . 37 4.3 Polish spaces . 39 4.4 Borel sets . 43 4.5 Analytic sets . 46 4.6 Lebesgue's mistake . 48 iii iv CONTENTS 5 Formal logic 51 5.1 Propositional logic . 51 5.1.1 Propositional logic: syntax . 51 5.1.2 Propositional logic: semantics . 52 5.1.3 Propositional logic: completeness . 53 5.2 First order logic . 56 5.2.1 First order logic: syntax . 56 5.2.2 First order logic: semantics . 59 5.2.3 Completeness theorem . 60 6 Model theory 67 6.1 Basic notions . 67 6.2 Ultraproducts and nonstandard analysis . 68 6.3 Quantifier elimination and the real closed fields . -

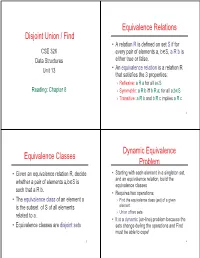

Disjoint Union / Find Equivalence Relations Equivalence Classes

Equivalence Relations Disjoint Union / Find • A relation R is defined on set S if for CSE 326 every pair of elements a, b∈S, a R b is Data Structures either true or false. Unit 13 • An equivalence relation is a relation R that satisfies the 3 properties: › Reflexive: a R a for all a∈S Reading: Chapter 8 › Symmetric: a R b iff b R a; for all a,b∈S › Transitive: a R b and b R c implies a R c 2 Dynamic Equivalence Equivalence Classes Problem • Given an equivalence relation R, decide • Starting with each element in a singleton set, whether a pair of elements a,b∈S is and an equivalence relation, build the equivalence classes such that a R b. • Requires two operations: • The equivalence class of an element a › Find the equivalence class (set) of a given is the subset of S of all elements element › Union of two sets related to a. • It is a dynamic (on-line) problem because the • Equivalence classes are disjoint sets sets change during the operations and Find must be able to cope! 3 4 Disjoint Union - Find Union • Maintain a set of disjoint sets. • Union(x,y) – take the union of two sets › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} named x and y • Each set has a unique name, one of its › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} members › Union(5,1) › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} {3,5,7,1,6}, {4,2,8}, {9}, 5 6 Find An Application • Find(x) – return the name of the set • Build a random maze by erasing edges.