MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED from PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES §1. Introduction. a Family a of Infinite Subsets of Ω Is Called

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of Abbreviations

Notes: c F.P. Greenleaf, 2000-2014 v43-s14sets.tex (version 1/1/2014) Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of abbreviations. Below we list some standard math symbols that will be used as shorthand abbreviations throughout this course. means “for all; for every” • ∀ means “there exists (at least one)” • ∃ ! means “there exists exactly one” • ∃ s.t. means “such that” • = means “implies” • ⇒ means “if and only if” • ⇐⇒ x A means “the point x belongs to a set A;” x / A means “x is not in A” • ∈ ∈ N denotes the set of natural numbers (counting numbers) 1, 2, 3, • · · · Z denotes the set of all integers (positive, negative or zero) • Q denotes the set of rational numbers • R denotes the set of real numbers • C denotes the set of complex numbers • x A : P (x) If A is a set, this denotes the subset of elements x in A such that •statement { ∈ P (x)} is true. As examples of the last notation for specifying subsets: x R : x2 +1 2 = ( , 1] [1, ) { ∈ ≥ } −∞ − ∪ ∞ x R : x2 +1=0 = { ∈ } ∅ z C : z2 +1=0 = +i, i where i = √ 1 { ∈ } { − } − 1.2 Basic facts from set theory. Next we review the basic definitions and notations of set theory, which will be used throughout our discussions of algebra. denotes the empty set, the set with nothing in it • ∅ x A means that the point x belongs to a set A, or that x is an element of A. • ∈ A B means A is a subset of B – i.e. -

MATH 361 Homework 9

MATH 361 Homework 9 Royden 3.3.9 First, we show that for any subset E of the real numbers, Ec + y = (E + y)c (translating the complement is equivalent to the complement of the translated set). Without loss of generality, assume E can be written as c an open interval (e1; e2), so that E + y is represented by the set fxjx 2 (−∞; e1 + y) [ (e2 + y; +1)g. This c is equal to the set fxjx2 = (e1 + y; e2 + y)g, which is equivalent to the set (E + y) . Second, Let B = A − y. From Homework 8, we know that outer measure is invariant under translations. Using this along with the fact that E is measurable: m∗(A) = m∗(B) = m∗(B \ E) + m∗(B \ Ec) = m∗((B \ E) + y) + m∗((B \ Ec) + y) = m∗(((A − y) \ E) + y) + m∗(((A − y) \ Ec) + y) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (Ec + y)) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (E + y)c) The last line follows from Ec + y = (E + y)c. Royden 3.3.10 First, since E1;E2 2 M and M is a σ-algebra, E1 [ E2;E1 \ E2 2 M. By the measurability of E1 and E2: ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E1) = m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E2) = m (E2 \ E1) + m (E2 \ E1) ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c m (E1) + m (E2) = 2m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c = m (E1 \ E2) + [m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2)] c c Second, E1 \ E2, E1 \ E2, and E1 \ E2 are disjoint sets whose union is equal to E1 [ E2. -

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55B

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55b 1. Give an example of a subset A ⊂ R such that, by repeatedly taking closures and complements. Take A := (−5; −4)−Q [[−4; −3][f2g[[−1; 0][(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ (4; 5)\Q . (The number of intervals in this sets is unnecessarily large, but, as Kevin suggested, taking a set that is complement-symmetric about 0 cuts down the verification in half. Note that this set is the union of f0g[(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ ([4; 5] \ Q) and the complement of the reflection of this set about the the origin). Because of this symmetry, we only need to verify that the closure- complement-closure sequence of the set f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q consists of seven distinct sets. Here are the (first) seven members of this sequence; from the eighth member the sets start repeating period- ically: f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q ; f0g [ [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 0) [ (0; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1); (−∞; 1] [ [3; 4] [ [5; 1); (1; 3) [ (4; 5); [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1). Thus, by symmetry, both the closure- complement-closure and complement-closure-complement sequences of A consist of seven distinct sets, and hence there is a total of 14 different sets obtained from A by taking closures and complements. Remark. That 14 is the maximal possible number of sets obtainable for any metric space is the Kuratowski complement-closure problem. This is proved by noting that, denoting respectively the closure and com- plement operators by a and b and by e the identity operator, the relations a2 = a; b2 = e, and aba = abababa take place, and then one can simply list all 14 elements of the monoid ha; b j a2 = a; b2 = e; aba = abababai. -

ON the CONSTRUCTION of NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES from EXISTING ONES Consider a Function F

ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES FROM EXISTING ONES EMILY RIEHL Abstract. In this note, we introduce a guiding principle to define topologies for a wide variety of spaces built from existing topological spaces. The topolo- gies so-constructed will have a universal property taking one of two forms. If the topology is the coarsest so that a certain condition holds, we will give an elementary characterization of all continuous functions taking values in this new space. Alternatively, if the topology is the finest so that a certain condi- tion holds, we will characterize all continuous functions whose domain is the new space. Consider a function f : X ! Y between a pair of sets. If Y is a topological space, we could define a topology on X by asking that it is the coarsest topology so that f is continuous. (The finest topology making f continuous is the discrete topology.) Explicitly, a subbasis of open sets of X is given by the preimages of open sets of Y . With this definition, a function W ! X, where W is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function W ! Y is continuous. On the other hand, if X is assumed to be a topological space, we could define a topology on Y by asking that it is the finest topology so that f is continuous. (The coarsest topology making f continuous is the indiscrete topology.) Explicitly, a subset of Y is open if and only if its preimage in X is open. With this definition, a function Y ! Z, where Z is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function X ! Z is continuous. -

Cardinality of Wellordered Disjoint Unions of Quotients of Smooth Equivalence Relations on R with All Classes Countable Is the Main Result of the Paper

CARDINALITY OF WELLORDERED DISJOINT UNIONS OF QUOTIENTS OF SMOOTH EQUIVALENCE RELATIONS WILLIAM CHAN AND STEPHEN JACKSON Abstract. Assume ZF + AD+ + V = L(P(R)). Let ≈ denote the relation of being in bijection. Let κ ∈ ON and hEα : α<κi be a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes countable and for all α<κ, R R R R R /Eα ≈ . Then the disjoint union Fα<κ /Eα is in bijection with × κ and Fα<κ /Eα has the J´onsson property. + <ω Assume ZF + AD + V = L(P(R)). A set X ⊆ [ω1] 1 has a sequence hEα : α<ω1i of equivalence relations on R such that R/Eα ≈ R and X ≈ F R/Eα if and only if R ⊔ ω1 injects into X. α<ω1 ω ω Assume AD. Suppose R ⊆ [ω1] × R is a relation such that for all f ∈ [ω1] , Rf = {x ∈ R : R(f,x)} ω is nonempty and countable. Then there is an uncountable X ⊆ ω1 and function Φ : [X] → R which uniformizes R on [X]ω: that is, for all f ∈ [X]ω, R(f, Φ(f)). Under AD, if κ is an ordinal and hEα : α<κi is a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes ω R countable, then [ω1] does not inject into Fα<κ /Eα. 1. Introduction The original motivation for this work comes from the study of a simple combinatorial property of sets using only definable methods. The combinatorial property of concern is the J´onsson property: Let X be any n n <ω n set. -

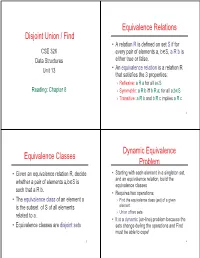

Disjoint Union / Find Equivalence Relations Equivalence Classes

Equivalence Relations Disjoint Union / Find • A relation R is defined on set S if for CSE 326 every pair of elements a, b∈S, a R b is Data Structures either true or false. Unit 13 • An equivalence relation is a relation R that satisfies the 3 properties: › Reflexive: a R a for all a∈S Reading: Chapter 8 › Symmetric: a R b iff b R a; for all a,b∈S › Transitive: a R b and b R c implies a R c 2 Dynamic Equivalence Equivalence Classes Problem • Given an equivalence relation R, decide • Starting with each element in a singleton set, whether a pair of elements a,b∈S is and an equivalence relation, build the equivalence classes such that a R b. • Requires two operations: • The equivalence class of an element a › Find the equivalence class (set) of a given is the subset of S of all elements element › Union of two sets related to a. • It is a dynamic (on-line) problem because the • Equivalence classes are disjoint sets sets change during the operations and Find must be able to cope! 3 4 Disjoint Union - Find Union • Maintain a set of disjoint sets. • Union(x,y) – take the union of two sets › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} named x and y • Each set has a unique name, one of its › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} members › Union(5,1) › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} {3,5,7,1,6}, {4,2,8}, {9}, 5 6 Find An Application • Find(x) – return the name of the set • Build a random maze by erasing edges. -

Handout #4: Connected Metric Spaces

Connected Sets Math 331, Handout #4 You probably have some intuitive idea of what it means for a metric space to be \connected." For example, the real number line, R, seems to be connected, but if you remove a point from it, it becomes \disconnected." However, it is not really clear how to define connected metric spaces in general. Furthermore, we want to say what it means for a subset of a metric space to be connected, and that will require us to look more closely at subsets of metric spaces than we have so far. We start with a definition of connected metric space. Note that, similarly to compactness and continuity, connectedness is actually a topological property rather than a metric property, since it can be defined entirely in terms of open sets. Definition 1. Let (M; d) be a metric space. We say that (M; d) is a connected metric space if and only if M cannot be written as a disjoint union N = X [ Y where X and Y are both non-empty open subsets of M. (\Disjoint union" means that M = X [ Y and X \ Y = ?.) A metric space that is not connected is said to be disconnnected. Theorem 1. A metric space (M; d) is connected if and only if the only subsets of M that are both open and closed are M and ?. Equivalently, (M; d) is disconnected if and only if it has a non-empty, proper subset that is both open and closed. Proof. Suppose (M; d) is a connected metric space. -

Real Analysis 1 Math 623 Notes by Patrick Lei, May 2020

Real Analysis 1 Math 623 Notes by Patrick Lei, May 2020 Lectures by Robin Young, Fall 2018 University of Massachusetts, Amherst Disclaimer These notes are a May 2020 transcription of handwritten notes taken during lecture in Fall 2018. Any errors are mine and not the instructor’s. In addition, my notes are picture-free (but will include commutative diagrams) and are a mix of my mathematical style (omit lengthy computations, use category theory) and that of the instructor. If you find any errors, please contact me at [email protected]. Contents Contents • 2 1 Lebesgue Measure • 3 1.1 Motivation for the Course • 3 1.2 Basic Notions • 4 1.3 Rectangles • 5 1.4 Outer Measure • 6 1.5 Measurable Sets • 7 1.6 Measurable Functions • 10 2 Integration • 13 2.1 Defining the Integral • 13 2.2 Some Convergence Results • 15 2.3 Vector Space of Integrable Functions • 16 2.4 Symmetries • 18 3 Differentiation • 20 3.1 Integration and Differentiation • 20 3.2 Kernels • 22 3.3 Differentiation • 26 3.4 Bounded Variation • 28 3.5 Absolute Continuity • 30 4 General Measures • 33 4.1 Outer Measures • 34 4.2 Results and Applications • 35 4.3 Signed Measures • 36 2 1 Lebesgue Measure 1.1 Motivation for the Course We will consider some examples that show us some fundamental problems in analysis. Example 1.1 (Fourier Series). Let f be periodic on [0, 2π]. Then if f is sufficiently nice, we can write inx f(x) = ane , n X 1 2π inx where an = 2π 0 f(x)e dx. -

2 Values and Types

2 Values and Types . Types of values. Primitive, composite, recursive types. Type systems: static vs dynamic typing, type completeness. Expressions. Implementation notes. © 2004, D.A. Watt, University of Glasgow / C. Huizing TU/e 1 1 Types (1) . Values are grouped into types according to the operations that may be performed on them. Different PLs support different types of values (according to their intended application areas): • Ada: booleans, characters, enumerands, integers, real numbers, records, arrays, discriminated records, objects (tagged records), strings, pointers to data, pointers to procedures. • C: enumerands, integers, real numbers, structures, arrays, unions, pointers to variables, pointers to functions. • Java: booleans, integers, real numbers, arrays, objects. • Haskell: booleans, characters, integers, real numbers, tuples, disjoint unions, lists, recursive types. 2 2 Types (2) . Roughly speaking, a type is a set of values: • v is a value of type T if v ∈ T. E is an expression of type T if E is guaranteed to yield a value of type T. But only certain sets of values are types: • {false, true} is a type, since the operations not, and, and or operate uniformly over the values false and true. • {…, –2, –1, 0, +1, +2, …} is a type, since operations such as addition and multiplication operate uniformly over all these values. • {13, true, Monday} is not considered to be a type, since there are no useful operations over this set of values. 3 3 Types (3) . More precisely, a type is a set of values, equipped with one or more operations that can be applied uniformly to all these values. The cardinality of a type T, written #T, is the number of values of type T. -

Open Subsets of R

Open Subsets of R Definition. (−∞; a), (a; 1), (−∞; 1), (a; b) are the open intervals of R. (Note that these are the connected open subsets of R.) Theorem. Every open subset U of R can be uniquely expressed as a countable union of disjoint open intervals. The end points of the intervals do not belong to U. Proof. Let U ⊂ R be open. For each x 2 U we will find the \maximal" open interval Ix s.t. x 2 Ix ⊂ U. Here \maximal" means that for any open interval J s.t x 2 J ⊂ U, we have J ⊂ Ix. Let x 2 U. Define Ix = (ax; bx), where ax = inf fa 2 R j (a; x) ⊂ Ug, and bx = sup fb 2 R j (x; b) ⊂ Ug. Either could be infinite. They are well defined since 9 an open interval I s.t x 2 I ⊂ U, because U is open. Clearly, x 2 Ix ⊂ U. Suppose J = (p; q) is s.t. x 2 J ⊂ U. Then (p; x) ⊂ U so p ≥ ax. Likewise q ≤ bx. Thus, J ⊂ Ix and so Ix is indeed maximal. Suppose ax 2 U. (In particular we are supposing ax is finite.) Then 9 > 0 s.t. (ax − , ax + ) ⊂ U. The (ax − , bx) is larger than Ix contradicting maximality. Thus, ax 2= U and likewise bx 2= U. 1 2 Claim. For x; y 2 U, the intervals Ix and Iy are either disjoint or identical. Proof. If Ix \ Iy 6= ;, then Ix [ Iy is an open interval. Since x 2 Ix [ Iy ⊂ U, we have, by maximality, Ix [ Iy ⊂ Ix. -

The Arithmetic of Cardinal Numbers

The arithmetic of cardinal numbers We wish to extend the familiar operations of addition, multiplication and expo- nentiation of the natural numbers so as to apply to all cardinal numbers. We start with addition and multiplication, then go on consider the unary exponen- tiation function assigning 2 n to each number n and finally the general binary exponentiation operation assigning mn to numbers n, m . Addition and Multiplication Lemma 2 For finite sets A, B , (i) If A ∩ B = ∅ then A ∪ B is finite and |A ∪ B| = |A| + |B|, (ii) A × B is finite and |A × B| = |A| · | B|. Proof see Example 1.9. For sets A, B let A + B = ( {0} × A) ∪ ({1} × B). We call this the disjoint union of A and B. Lemma 3 If A ∼ C and B ∼ D then (i) A + B ∼ C + D, (ii) A × B ∼ C × D. Proof Let f : A ∼ C, g : B ∼ D. Then h : A + B → C + D and e : A × B → C × D defined by h(0 , a ) = (0 , f (a)) for a ∈ A, h (1 , b ) = (1 , g (b)) for b ∈ B e(a, b ) = ( f(a), g (b)) for a ∈ A, b ∈ B are bijections so the result follows. Definition 10 For cardinal numbers n, m let (i) n + m = |A + B| for some/any sets A, B such that n = |A| and m = |B|, (ii) n · m = |A × B| for some/any sets A, B such that n = |A| and m = |B|, Note that the previous lemma ensures that these definitions make sense. Proposition 21 For cardinal numbers n, m and any sets A, B such that A ∩ B = ∅ and n = |A| and m = |B| we have n + m = |A ∪ B|. -

Producing New Bijections From

ro duing xew fijetions from yld @to pp er in edvnes in wthemtisA epril PPD IWWR hvid peldmn niversity of xew rmpshire tmes ropp wsshusetts snstitute of ehnology efeg por ny purely omintoril onstrution tht pro dues new nite sets from given onesD ijetion etween two given sets nturlly determines ijetion etween the orresp onding onstruted setsF e investigte the p ossiility of going in reverseX dening ijetion etween the originl o jets from given ijetion etween the onstruted o jetsD in eet neling4 the onstrutionF e present preise formultion of this question nd then give onrete riterion for determining whether suh nelltion is p ossileF sf the riterion is stisedD then nelltion pro edure existsD nd indeedD for mny of the onstrutions tht we hve studied p olynomilEtime nellE tion pro edure hs een foundY on the other hndD when the riterion is not stisedD no pro edureD however omplitedD n p erform the nelltionF he elerted involution priniple of qrsi nd wilne ts into our ruri one it is reognized s thinly disguised form of neling disjoint union with xed setD itself well{known tehnique tht ts into our theoretil frmeworkF e show tht the onstrution tht forms the grtesin pro dut of given set with some otherD xed set nnot in generl e neledD ut tht it n e neled in the se where the xed set rries distinguished elementF e lso show tht the onstrution tht tkes the mth grtesin p ower of given set n e neledD ut tht the onstrution tht forms the p ower set of given set nnotF uey wordsX fijetionD ijetive pro ofD qEsetD grtesin p owerD p ower