Solutions to Homework 2 Problem 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of Abbreviations

Notes: c F.P. Greenleaf, 2000-2014 v43-s14sets.tex (version 1/1/2014) Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of abbreviations. Below we list some standard math symbols that will be used as shorthand abbreviations throughout this course. means “for all; for every” • ∀ means “there exists (at least one)” • ∃ ! means “there exists exactly one” • ∃ s.t. means “such that” • = means “implies” • ⇒ means “if and only if” • ⇐⇒ x A means “the point x belongs to a set A;” x / A means “x is not in A” • ∈ ∈ N denotes the set of natural numbers (counting numbers) 1, 2, 3, • · · · Z denotes the set of all integers (positive, negative or zero) • Q denotes the set of rational numbers • R denotes the set of real numbers • C denotes the set of complex numbers • x A : P (x) If A is a set, this denotes the subset of elements x in A such that •statement { ∈ P (x)} is true. As examples of the last notation for specifying subsets: x R : x2 +1 2 = ( , 1] [1, ) { ∈ ≥ } −∞ − ∪ ∞ x R : x2 +1=0 = { ∈ } ∅ z C : z2 +1=0 = +i, i where i = √ 1 { ∈ } { − } − 1.2 Basic facts from set theory. Next we review the basic definitions and notations of set theory, which will be used throughout our discussions of algebra. denotes the empty set, the set with nothing in it • ∅ x A means that the point x belongs to a set A, or that x is an element of A. • ∈ A B means A is a subset of B – i.e. -

A Class of Symmetric Difference-Closed Sets Related to Commuting Involutions John Campbell

A class of symmetric difference-closed sets related to commuting involutions John Campbell To cite this version: John Campbell. A class of symmetric difference-closed sets related to commuting involutions. Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science, DMTCS, 2017, Vol 19 no. 1. hal-01345066v4 HAL Id: hal-01345066 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01345066v4 Submitted on 18 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science DMTCS vol. 19:1, 2017, #8 A class of symmetric difference-closed sets related to commuting involutions John M. Campbell York University, Canada received 19th July 2016, revised 15th Dec. 2016, 1st Feb. 2017, accepted 10th Feb. 2017. Recent research on the combinatorics of finite sets has explored the structure of symmetric difference-closed sets, and recent research in combinatorial group theory has concerned the enumeration of commuting involutions in Sn and An. In this article, we consider an interesting combination of these two subjects, by introducing classes of symmetric difference-closed sets of elements which correspond in a natural way to commuting involutions in Sn and An. We consider the natural combinatorial problem of enumerating symmetric difference-closed sets consisting of subsets of sets consisting of pairwise disjoint 2-subsets of [n], and the problem of enumerating symmetric difference-closed sets consisting of elements which correspond to commuting involutions in An. -

MATH 361 Homework 9

MATH 361 Homework 9 Royden 3.3.9 First, we show that for any subset E of the real numbers, Ec + y = (E + y)c (translating the complement is equivalent to the complement of the translated set). Without loss of generality, assume E can be written as c an open interval (e1; e2), so that E + y is represented by the set fxjx 2 (−∞; e1 + y) [ (e2 + y; +1)g. This c is equal to the set fxjx2 = (e1 + y; e2 + y)g, which is equivalent to the set (E + y) . Second, Let B = A − y. From Homework 8, we know that outer measure is invariant under translations. Using this along with the fact that E is measurable: m∗(A) = m∗(B) = m∗(B \ E) + m∗(B \ Ec) = m∗((B \ E) + y) + m∗((B \ Ec) + y) = m∗(((A − y) \ E) + y) + m∗(((A − y) \ Ec) + y) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (Ec + y)) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (E + y)c) The last line follows from Ec + y = (E + y)c. Royden 3.3.10 First, since E1;E2 2 M and M is a σ-algebra, E1 [ E2;E1 \ E2 2 M. By the measurability of E1 and E2: ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E1) = m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E2) = m (E2 \ E1) + m (E2 \ E1) ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c m (E1) + m (E2) = 2m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c = m (E1 \ E2) + [m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2)] c c Second, E1 \ E2, E1 \ E2, and E1 \ E2 are disjoint sets whose union is equal to E1 [ E2. -

Natural Numerosities of Sets of Tuples

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 367, Number 1, January 2015, Pages 275–292 S 0002-9947(2014)06136-9 Article electronically published on July 2, 2014 NATURAL NUMEROSITIES OF SETS OF TUPLES MARCO FORTI AND GIUSEPPE MORANA ROCCASALVO Abstract. We consider a notion of “numerosity” for sets of tuples of natural numbers that satisfies the five common notions of Euclid’s Elements, so it can agree with cardinality only for finite sets. By suitably axiomatizing such a no- tion, we show that, contrasting to cardinal arithmetic, the natural “Cantorian” definitions of order relation and arithmetical operations provide a very good algebraic structure. In fact, numerosities can be taken as the non-negative part of a discretely ordered ring, namely the quotient of a formal power series ring modulo a suitable (“gauge”) ideal. In particular, special numerosities, called “natural”, can be identified with the semiring of hypernatural numbers of appropriate ultrapowers of N. Introduction In this paper we consider a notion of “equinumerosity” on sets of tuples of natural numbers, i.e. an equivalence relation, finer than equicardinality, that satisfies the celebrated five Euclidean common notions about magnitudines ([8]), including the principle that “the whole is greater than the part”. This notion preserves the basic properties of equipotency for finite sets. In particular, the natural Cantorian definitions endow the corresponding numerosities with a structure of a discretely ordered semiring, where 0 is the size of the emptyset, 1 is the size of every singleton, and greater numerosity corresponds to supersets. This idea of “Euclidean” numerosity has been recently investigated by V. -

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55B

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55b 1. Give an example of a subset A ⊂ R such that, by repeatedly taking closures and complements. Take A := (−5; −4)−Q [[−4; −3][f2g[[−1; 0][(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ (4; 5)\Q . (The number of intervals in this sets is unnecessarily large, but, as Kevin suggested, taking a set that is complement-symmetric about 0 cuts down the verification in half. Note that this set is the union of f0g[(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ ([4; 5] \ Q) and the complement of the reflection of this set about the the origin). Because of this symmetry, we only need to verify that the closure- complement-closure sequence of the set f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q consists of seven distinct sets. Here are the (first) seven members of this sequence; from the eighth member the sets start repeating period- ically: f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q ; f0g [ [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 0) [ (0; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1); (−∞; 1] [ [3; 4] [ [5; 1); (1; 3) [ (4; 5); [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1). Thus, by symmetry, both the closure- complement-closure and complement-closure-complement sequences of A consist of seven distinct sets, and hence there is a total of 14 different sets obtained from A by taking closures and complements. Remark. That 14 is the maximal possible number of sets obtainable for any metric space is the Kuratowski complement-closure problem. This is proved by noting that, denoting respectively the closure and com- plement operators by a and b and by e the identity operator, the relations a2 = a; b2 = e, and aba = abababa take place, and then one can simply list all 14 elements of the monoid ha; b j a2 = a; b2 = e; aba = abababai. -

MTH 304: General Topology Semester 2, 2017-2018

MTH 304: General Topology Semester 2, 2017-2018 Dr. Prahlad Vaidyanathan Contents I. Continuous Functions3 1. First Definitions................................3 2. Open Sets...................................4 3. Continuity by Open Sets...........................6 II. Topological Spaces8 1. Definition and Examples...........................8 2. Metric Spaces................................. 11 3. Basis for a topology.............................. 16 4. The Product Topology on X × Y ...................... 18 Q 5. The Product Topology on Xα ....................... 20 6. Closed Sets.................................. 22 7. Continuous Functions............................. 27 8. The Quotient Topology............................ 30 III.Properties of Topological Spaces 36 1. The Hausdorff property............................ 36 2. Connectedness................................. 37 3. Path Connectedness............................. 41 4. Local Connectedness............................. 44 5. Compactness................................. 46 6. Compact Subsets of Rn ............................ 50 7. Continuous Functions on Compact Sets................... 52 8. Compactness in Metric Spaces........................ 56 9. Local Compactness.............................. 59 IV.Separation Axioms 62 1. Regular Spaces................................ 62 2. Normal Spaces................................ 64 3. Tietze's extension Theorem......................... 67 4. Urysohn Metrization Theorem........................ 71 5. Imbedding of Manifolds.......................... -

ON the CONSTRUCTION of NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES from EXISTING ONES Consider a Function F

ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES FROM EXISTING ONES EMILY RIEHL Abstract. In this note, we introduce a guiding principle to define topologies for a wide variety of spaces built from existing topological spaces. The topolo- gies so-constructed will have a universal property taking one of two forms. If the topology is the coarsest so that a certain condition holds, we will give an elementary characterization of all continuous functions taking values in this new space. Alternatively, if the topology is the finest so that a certain condi- tion holds, we will characterize all continuous functions whose domain is the new space. Consider a function f : X ! Y between a pair of sets. If Y is a topological space, we could define a topology on X by asking that it is the coarsest topology so that f is continuous. (The finest topology making f continuous is the discrete topology.) Explicitly, a subbasis of open sets of X is given by the preimages of open sets of Y . With this definition, a function W ! X, where W is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function W ! Y is continuous. On the other hand, if X is assumed to be a topological space, we could define a topology on Y by asking that it is the finest topology so that f is continuous. (The coarsest topology making f continuous is the indiscrete topology.) Explicitly, a subset of Y is open if and only if its preimage in X is open. With this definition, a function Y ! Z, where Z is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function X ! Z is continuous. -

MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED from PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES §1. Introduction. a Family a of Infinite Subsets of Ω Is Called

The Journal of Symbolic Logic Volume 00, Number 0, XXX 0000 MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED FROM PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES JORG¨ BRENDLE AND YURII KHOMSKII 1 Abstract. We prove the consistency of b > @1 together with the existence of a Π1- definable mad family, answering a question posed by Friedman and Zdomskyy in [7, Ques- tion 16]. For the proof we construct a mad family in L which is an @1-union of perfect a.d. sets, such that this union remains mad in the iterated Hechler extension. The construction also leads us to isolate a new cardinal invariant, the Borel almost-disjointness number aB , defined as the least number of Borel a.d. sets whose union is a mad family. Our proof yields the consistency of aB < b (and hence, aB < a). x1. Introduction. A family A of infinite subsets of ! is called almost disjoint (a.d.) if any two elements a; b of A have finite intersection. A family A is called maximal almost disjoint, or mad, if it is an infinite a.d. family which is maximal with respect to that property|in other words, 8a 9b 2 A (ja \ bj = !). The starting point of this paper is the following theorem of Adrian Mathias [11, Corollary 4.7]: Theorem 1.1 (Mathias). There are no analytic mad families. 1 On the other hand, it is easy to see that in L there is a Σ2 definable mad family. In [12, Theorem 8.23], Arnold Miller used a sophisticated method to 1 prove the seemingly stronger result that in L there is a Π1 definable mad family. -

Cardinality of Wellordered Disjoint Unions of Quotients of Smooth Equivalence Relations on R with All Classes Countable Is the Main Result of the Paper

CARDINALITY OF WELLORDERED DISJOINT UNIONS OF QUOTIENTS OF SMOOTH EQUIVALENCE RELATIONS WILLIAM CHAN AND STEPHEN JACKSON Abstract. Assume ZF + AD+ + V = L(P(R)). Let ≈ denote the relation of being in bijection. Let κ ∈ ON and hEα : α<κi be a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes countable and for all α<κ, R R R R R /Eα ≈ . Then the disjoint union Fα<κ /Eα is in bijection with × κ and Fα<κ /Eα has the J´onsson property. + <ω Assume ZF + AD + V = L(P(R)). A set X ⊆ [ω1] 1 has a sequence hEα : α<ω1i of equivalence relations on R such that R/Eα ≈ R and X ≈ F R/Eα if and only if R ⊔ ω1 injects into X. α<ω1 ω ω Assume AD. Suppose R ⊆ [ω1] × R is a relation such that for all f ∈ [ω1] , Rf = {x ∈ R : R(f,x)} ω is nonempty and countable. Then there is an uncountable X ⊆ ω1 and function Φ : [X] → R which uniformizes R on [X]ω: that is, for all f ∈ [X]ω, R(f, Φ(f)). Under AD, if κ is an ordinal and hEα : α<κi is a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes ω R countable, then [ω1] does not inject into Fα<κ /Eα. 1. Introduction The original motivation for this work comes from the study of a simple combinatorial property of sets using only definable methods. The combinatorial property of concern is the J´onsson property: Let X be any n n <ω n set. -

Old Notes from Warwick, Part 1

Measure Theory, MA 359 Handout 1 Valeriy Slastikov Autumn, 2005 1 Measure theory 1.1 General construction of Lebesgue measure In this section we will do the general construction of σ-additive complete measure by extending initial σ-additive measure on a semi-ring to a measure on σ-algebra generated by this semi-ring and then completing this measure by adding to the σ-algebra all the null sets. This section provides you with the essentials of the construction and make some parallels with the construction on the plane. Throughout these section we will deal with some collection of sets whose elements are subsets of some fixed abstract set X. It is not necessary to assume any topology on X but for simplicity you may imagine X = Rn. We start with some important definitions: Definition 1.1 A nonempty collection of sets S is a semi-ring if 1. Empty set ? 2 S; 2. If A 2 S; B 2 S then A \ B 2 S; n 3. If A 2 S; A ⊃ A1 2 S then A = [k=1Ak, where Ak 2 S for all 1 ≤ k ≤ n and Ak are disjoint sets. If the set X 2 S then S is called semi-algebra, the set X is called a unit of the collection of sets S. Example 1.1 The collection S of intervals [a; b) for all a; b 2 R form a semi-ring since 1. empty set ? = [a; a) 2 S; 2. if A 2 S and B 2 S then A = [a; b) and B = [c; d). -

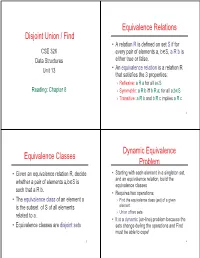

Disjoint Union / Find Equivalence Relations Equivalence Classes

Equivalence Relations Disjoint Union / Find • A relation R is defined on set S if for CSE 326 every pair of elements a, b∈S, a R b is Data Structures either true or false. Unit 13 • An equivalence relation is a relation R that satisfies the 3 properties: › Reflexive: a R a for all a∈S Reading: Chapter 8 › Symmetric: a R b iff b R a; for all a,b∈S › Transitive: a R b and b R c implies a R c 2 Dynamic Equivalence Equivalence Classes Problem • Given an equivalence relation R, decide • Starting with each element in a singleton set, whether a pair of elements a,b∈S is and an equivalence relation, build the equivalence classes such that a R b. • Requires two operations: • The equivalence class of an element a › Find the equivalence class (set) of a given is the subset of S of all elements element › Union of two sets related to a. • It is a dynamic (on-line) problem because the • Equivalence classes are disjoint sets sets change during the operations and Find must be able to cope! 3 4 Disjoint Union - Find Union • Maintain a set of disjoint sets. • Union(x,y) – take the union of two sets › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} named x and y • Each set has a unique name, one of its › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} members › Union(5,1) › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} {3,5,7,1,6}, {4,2,8}, {9}, 5 6 Find An Application • Find(x) – return the name of the set • Build a random maze by erasing edges. -

Equivalents to the Axiom of Choice and Their Uses A

EQUIVALENTS TO THE AXIOM OF CHOICE AND THEIR USES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Mathematics California State University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Mathematics By James Szufu Yang c 2015 James Szufu Yang ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The thesis of James Szufu Yang is approved. Mike Krebs, Ph.D. Kristin Webster, Ph.D. Michael Hoffman, Ph.D., Committee Chair Grant Fraser, Ph.D., Department Chair California State University, Los Angeles June 2015 iii ABSTRACT Equivalents to the Axiom of Choice and Their Uses By James Szufu Yang In set theory, the Axiom of Choice (AC) was formulated in 1904 by Ernst Zermelo. It is an addition to the older Zermelo-Fraenkel (ZF) set theory. We call it Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory with the Axiom of Choice and abbreviate it as ZFC. This paper starts with an introduction to the foundations of ZFC set the- ory, which includes the Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms, partially ordered sets (posets), the Cartesian product, the Axiom of Choice, and their related proofs. It then intro- duces several equivalent forms of the Axiom of Choice and proves that they are all equivalent. In the end, equivalents to the Axiom of Choice are used to prove a few fundamental theorems in set theory, linear analysis, and abstract algebra. This paper is concluded by a brief review of the work in it, followed by a few points of interest for further study in mathematics and/or set theory. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Between the two department requirements to complete a master's degree in mathematics − the comprehensive exams and a thesis, I really wanted to experience doing a research and writing a serious academic paper.