Rates of Return on Public Spending on Transport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rail User Express We Continue with the Usual Roundup of News

June 2020 Welcome to the Rail User Express RUX may be forwarded, or items reproduced (quoting sources). Anyone may request it as an email attachment, or opt to be notified when it is posted on the Railfuture (Rf) website. There is no charge for either service. Following GDPR, Railfuture Membership now maintains both lists. Please advise if you no longer wish to receive RUX or the link, or if you know of anyone who would like to be added. For more on any item, consult the relevant website, or ask the editor for the source material. As the rail industry recovers from Covid-19, passenger numbers may well be depleted. We must hope that this is not used as an excuse to delay or even shelve much-needed rail infrastructure projects. On the contrary, it is the ideal time to fast track them, and so make rail a greener alternative to both the car and the HGV. Access to stations should encourage bus use, cycling and walking, whilst providing for those with restricted mobility. Roger Smith We continue with the usual roundup of news items from groups around the UK. Please keep your contributions coming: they are all gratefully received. Friends of the Far North Line Exciting news! After many years of work behind the scenes, especially by Frank Roach of HITRANS (Highlands and Islands Transport Partnership), plans are in hand for a proper transport hub in Inverness. Although the present bus station is quite near the railway station, there are several sites in between. With the financial help of Transport Scotland, NR has purchased the former Royal Mail sorting office and car park, the TK Maxx and Sports Direct buildings, a public car park and Highland Rail House on the north side of Station Square. -

New Railway Stations in North and West Yorkshire Feasibility Study Final Report West Yorkshire Combined Authority

New Railway Stations in North and West Yorkshire Feasibility Study Final Report West Yorkshire Combined Authority 14 October 2014 New Railway Stations in North and West Yorkshire Feasibility Study Final Report Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for West Yorkshire Combined Authority‟s information and use in relation to a feasibility study assessing new railway station locations in North and West Yorkshire. Atkins Ltd assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. This document has 66 pages including the cover. Document history Job number: 5124741 Document ref: Metro New Railway Stations Study Report Revision Purpose description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Rev 0.1 Draft for client comment JB,CW CW JT JT 07/03/2014 Rev 0.2 Revised draft CW CW JT JT 23/06/2014 incorporating initial client comments and two additional Stage 2 sites Rev 1.0 Final report CW CW JT JT 14//10/14 Atkins Final Report | Version 1.0 | 14 October 2014 | 5124741 2 New Railway Stations in North and West Yorkshire Feasibility Study Final Report Table of contents Chapter Pages 1. Introduction 6 Background 6 Study Context 6 Report Structure 6 2. Site Locations 7 3. Assessment Methodology 9 Stage 1 – Preliminary Sift 9 Identifying the Initial Shortlist (End of Stage 1) 13 Stage 2 – Detailed Feasibility Assessment 15 End of Stage 2 - Final Shortlist 16 4. Stage 1 Assessment – Preliminary Sift 17 Stage 1 Assessment Results Summary by Line 17 Shortlisted Sites for Stage 2 29 5. -

Appraisal Methodology and Regional Economic Performance in the UK

Bennett Institute for Public Policy working paper no: 02/2018 The Imperial Treasury: appraisal methodology and regional economic performance in the UK July 2018 Diane Coyle & Marianne Sensier1 Conference version: under submission ABSTRACT The disparity between the least and most productive regions in the UK is extreme by the standards of most other OECD economies. While there are many contributory factors, this paper argues that an important one is the concentration of public investment in and around London and the South East. The appraisal process for infrastructure investment projects follows the procedures set out in the Treasury’s Green Book, with major funding allocation decisions almost wholly centralised. In this paper we argue that the official methodology has reinforced the regional imbalance of the UK economy; that recent changes to the appraisal methods are welcome but unlikely to redress the London bias in infrastructure decisions; and that although evidence-based appraisal is important, infrastructure investments also need to be based on a strategic view about economic development for the whole of the UK. Keywords: Infrastructure; spatial disparities; cost benefit analysis JEL codes: H54, O18, R11 1 University of Cambridge and University of Manchester respectively. Contact [email protected]. Our thanks to Tom Forth, Michael Kenny, Luke Raikes, Ron Martin and participants in conferences at the University of Bath and University of Cambridge for their comments. The authors are of course responsible for any errors or omissions. 1 Introduction The Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, commented in 2017 on his experience as chief secretary to the Treasury a decade earlier: “Officials took me through the cost-benefit analysis used by the Department for Transport and the Treasury to assess the viability of transport projects. -

"Restoring Your Railway" Fund Potential Candidates Scheme Type

"Restoring Your Railway" fund potential candidates DfT Potential Scheme Type of project Proposition headlines status Source Status Completion? Population Demography, benefits Notes Accelerating existing proposals, Ideas fund, New or restored stations EAST . Greater Cambridge becoming major jobs Road congestion relief, assist high Metro service intensity needed on Greater Cambridge rail New/improved rail cluster, needs more rail capacity for services, Cabs & P'boro CA, local All of western density high worth job clusters, Ely-Cambridge South, also allow for schemes corridors, more stations more stns eg Cambridge South A campaign, Railfuture Active project 2024 / 2029 Anglia zone growing populations East-West Rail Isolated Wisbech linked to main job centres Cabs & P'boro CA, local Wisbech, better Deprived and poorly linked Requires main line corridor upgrade Reopen mothballed line Cambridge and Peterborough, for economic campaign, Railfuture, March area growing town needing fast link to for through trains to work, not a Wisbech-March to passengers gains and social inclusion A S.Barclay MP, CfBT Active project 2024 connectivity jobs within 1 hour travel shuttle to March Growing Anglian town, scope for service to Initial phase of connections for Soham New/reopened stations Cambridge job clusters N Railfuture Proposed 2024 Soham and locality Poorly linked growing town Mildenhall redevelopment zone New rail corridor, Link Mildenhall airbase redevelopment with Mildenhall Large-scale redevelopment Continuation stage from Soham Mildenhall Line -

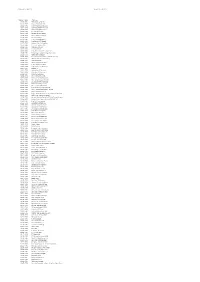

Station Or Halt Name Line Date Closed Station

Our Station Station or Halt Name Line Date Closed Station remains Date Visited number (Aberdeen) Holburn Street Deeside Railway (GNoSR) 1937 (Aberdeen) Hutcheon Street Denburn Valley Line (GNoSR) 1937 Abbey and West Dereham GER 1930 Abbey Foregate (Shrewsbury) S&WTN 1912 Abbey Junction NBR, CAL 1921 Abbey of Deer Platform London and North Eastern Railway 1970 Abbey Town NBR 1964 Abbeydore GWR 1941 Abbeyhill (Edinburgh) NBR 1964 Abbots Ripton GNR 1958 Abbots Wood Junction MR 1855 Abbotsbury GWR 1952 Abbotsford Ferry NBR 1931 Abbotsham Road BWH!&AR 1917 Aber (LNWR) Chester and Holyhead Railway 1960 Aberaman TVR 1964 Aberangell Mawddwy Railway/Cambrian Railways 1931 Aberavon (Seaside) Rhondda and Swansea Bay Railway 1962 Aberavon Town Rhondda and Swansea Bay Railway 1962 Aberayron GWR 1951 Aberbargoed B&MJR 1962 Aberbeeg GWR 1962 Aberbran N&B 1962 Abercairny Caledonian 1951 Abercamlais Neath and Brecon Railway 1962 Abercanaid GWR/Rhymney Jt 1951 Abercarn GWR 1962 Aberchalder HR/NBR 1933 Abercrave N&B 1932 Abercwmboi Halt TVR 1956 Abercynon North British Rail 2008 Aberdare Low Level TVR 1964 Aberdeen Ferryhill Aberdeen Railway 1864 Aberdeen Guild Street Aberdeen Railway 1867 Aberdeen Kittybrewster (3 stations of this name, on GNoSR2 lines; all closed) 1968 Aberdeen Waterloo GNoSR 1867 Aberderfyn Halt GWR 1915 Aberdylais Halt GWR 1964 Aberedw Cambrian Railways 1962 Aberfan Cambrian Railways/Rhymney Railway Jt 1951 Aberfeldy Highland Railway 1965 Aberford Aberford Railway 1924 Aberfoyle NBR 1951 Abergavenny Brecon Road Merthyr, Tredegar and -

North Eastern Railway Civil Engineering Drawings List

North Eastern Railway Civil Engineering Drawings List Description: The collection includes a minority of architectural plans, along with drawings of structures such as bridges and viaducts, maps of permanent way routes and alterations, signalling plans and diagrams, with a variety of miscellaneous components for structures and infrastructure. The collection comprises approximately 3500 plans, diagrams and maps on paper, wax linen and linen- backed cartridge paper. System of arrangement: The original arrangement of the drawings has been lost and they derive from a wide variety of applications within the architectural and civil engineering genres. The drawings have therefore been listed in the rolls in which they were found, and every effort made to record the variety of numbering systems used at different times by the railway company departments involved in creating and storing the drawings, representative of the different types of drawing. There is no one single and consistent numbering arrangement. Physical Characteristics: The drawings survive in a variety of formats and sizes – there are wax linen tracings, colour washed linenbacked original office drawings, drawings on cartridge paper, blueprints and other copying processes. Administrative/Biographical History: The North Eastern Railway Company was formed in 1854 as an amalgamation of the York & North Midland Railway, the Leeds Northern Railway and the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway. It continued to absorb other companies in the north eastern region of England over subsequent decades, including the Stockton & Darlington Railway, South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway and the West Hartlepool Railway. In 1923 the various railway companies of the United Kingdom were grouped into four large amalgamations. -

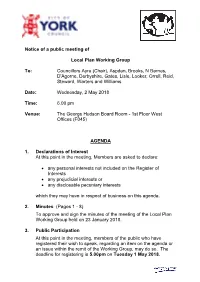

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Local Plan Working Group, 02/05

Notice of a public meeting of Local Plan Working Group To: Councillors Ayre (Chair), Aspden, Brooks, N Barnes, D'Agorne, Derbyshire, Gates, Lisle, Looker, Orrell, Reid, Steward, Warters and Williams Date: Wednesday, 2 May 2018 Time: 6.00 pm Venue: The George Hudson Board Room - 1st Floor West Offices (F045) AGENDA 1. Declarations of Interest At this point in the meeting, Members are asked to declare: any personal interests not included on the Register of Interests any prejudicial interests or any disclosable pecuniary interests which they may have in respect of business on this agenda. 2. Minutes (Pages 1 - 8) To approve and sign the minutes of the meeting of the Local Plan Working Group held on 23 January 2018. 3. Public Participation At this point in the meeting, members of the public who have registered their wish to speak, regarding an item on the agenda or an issue within the remit of the Working Group, may do so. The deadline for registering is 5.00pm on Tuesday 1 May 2018. Filming or Recording Meetings Please note that, subject to available resources, this meeting will be filmed and webcast, or recorded, including any registered public speakers who have given their permission. This broadcast can be viewed at http://www.york.gov.uk/webcasts. Residents are welcome to photograph, film or record Councillors and Officers at all meetings open to the press and public. This includes the use of social media reporting e.g. tweeting. Anyone wishing to film, record or take photos at any public meeting should contact the Democracy Officers (whose contact details are at the foot of this agenda) in advance of the meeting. -

C:\Users\User\Documents\My Eboo

201 We thank all the regular contributors to this bibliography and the societies who generously send us complimentary copies of their journals. ‘Ott.xxxx’ refers to an entry in Ottley’s Bibliography. Grahame Boyes and Matthew Searle SECTION G GENERAL GC TRANSPORT IN PARTICULAR REGIONS OF THE 11 COX, R. C. Telford in Ireland: work, opinions, influence. Proc. BRITISH ISLES Instn Civil Engrs: Engineering History & Heritage vol. 162 GC1b England — South West region (2009) pp. 51–60. 1 VAUGHAN, JOHN. Transport and industrial heritage – 121 WILKINS, NOEL P. Alexander Nimmo, master engineer 1783– Cornwall. Ian Allan, 2009. pp. 192. 140 photos (many col.). 1832: public works and civil surveys. Irish Academic Press, pp. 85–91, Canals; 130–50, Roads; 151–85, Railways. 2009. pp. 434. GC1c England — South East region GE TRANSPORT ENGINEERING 2 KRAEMER-JOHNSON, GLYN and BISHOP, JOHN. Bygone 13 ASHLEY, PETER. Built for Britain: bridges to beach huts. Kent. Ian Allan, 2009. pp. 80. 80 col. photos. Wiley, 2009. pp. 168. col. photos. Album of colour photos of scenes featuring road, rail and A pictorial album of characteristic structures. pp. 42–79, ferries, chiefly 1960s. Bridges; 102–17, Railways. 3 McCORMACK, KEVIN. Bygone Surrey. Ian Allan, 2009. pp. 14 McEWEN, ALAN. Historic steam boiler explosions. Sledge- 80. 80 col. photos. hammer Engg Press, 2009. pp. xv, 185. 170 illns. Album of colour photos of scenes featuring road and other 4 traction engine & 5 rly loco examples. transport, 1940s–70s. London GG TRANSPORT MANAGEMENT AND OPERATION 4 DARLEY, PETER (ed). Camden railway heritage trail: Primrose GG2 Passenger services Hill to Camden Lock and Chalk Farm. -

Leeds City Region HS2 Growth Strategy

Leeds City Region HS2 Growth Strategy Engagement Report The West Yorkshire Combined Authority Consultation and Engagement Team May 2018 Executive Summary Overall the response to the engagement activities was positive and showed strong support for the visions and principles outlined within the strategies. Numerous descriptive comments were provided to supplement quantitative data, though these varied widely both in terms of content and level of detail with most organisations focusing on elements of the strategies that would benefit their sector specifically or which highlighted potential within their area of expertise. Some of the key points and quotes are highlighted below: Support for the vision and principles: o “[We welcome] the Leeds City Region HS2 Growth Strategy, and endorse the overall approach around highlighting the step change in connectivity while focussing on harnessing the skills, supply chain and regeneration opportunities that high speed rail investment will provide for the whole region.” o “[We support] the preparation of a strategy for growth to secure maximum economic and social benefit from the construction of HS2 within the Leeds City Region” o “As an organisation with a strong interest in economic growth and the city’s development, we welcome the plans to create significant number of jobs and improve connectivity to both London and our northern city partners, unlocking the north’s economic potential, and transforming the city centre.” Support for the benefits of the strategies to the city’s workforce and in particular -

Yorkshire Rail Campaigner Number 51 – January 2021

Yorkshire Rail Campaigner Number 51 – January 2021 Yorkshire President: Alan Whitehouse: Vice-Presidents: Mike Crowhurst, Alan Williams & Chris Hyomes Where’s The Plan? Esk Valley Community Rail Partnership Press Release New Report exposes County Council’s lack of consultation or progress in five years on proposed Esk Valley line upgrade. Photo: Token exchange at Glaisdale. By Alan Williams. North Yorkshire County Council is not properly equipped to manage a rail infrastructure project and their consultants “were either not prepared or not sufficiently informed to explore innovative solutions as requested”. That’s the conclusion of a hard hitting report ‘Where’s the Plan?’ published today by the Esk Valley Railway Development Company, the Community Rail Partnership for the Whitby – Middlesbrough Esk Valley line. The Report claims that there has been almost no progress or proper consultation in the five years since the Partnership, along with the North Yorkshire Moors Railway and other local groups, persuaded Sirius Minerals to provide £4.5million of funding to improve the infrastructure on the Esk Valley rail line to enable the doubling of the service. …continued overleaf… Two forthcoming Railfuture joint branch webinars: • Saturday 30th January 2021 @ 14:00 Tony Baxter, Regional Director, North East, Northern Trains – “Challenging Times" • Saturday 27th February 2021 @ 14:00 Phil Smart, Railfuture Freight Group - "Freeing Up Castlefield Paths - New Freight Routes Around Manchester" • Saturday 17th April 2021 @ 14:00 Railfuture Yorkshire Branch Business Meeting online. Pass this newsletter to a friend when you’ve finished and help advertise Railfuture. 1 | Railfuture: Yorkshire Rail Campaigner 51 – January 2021 Despite the delay, there is still no agreed plan but astonishingly North Yorkshire County Council are proposing a ‘quick and dirty’ scheme to simply install additional restrictive and time consuming Victorian-era token machine signalling. -

Transforming the North's Railways: Northern and Transpennine

Transforming the North’s Railways Northern Rail Franchise TransPennine Express Rail Franchise Stakeholder Briefing Document and Consultation Response February 2015 The Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Department’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 Website www.gov.uk/dft General enquiries: https://forms.dft.gov.uk © Crown copyright 2015 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned 2 Contents Contents ................................................................................................... 3 Foreword.................................................................................................. -

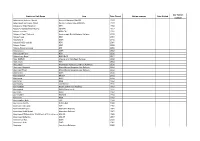

OP Project List GRIP 1-8 Report Date 26.01.17

OP Project List GRIP 1-8 Report Date 26.01.17 Project No. Stage Project T t e 100056 GRIP3 DB56 Kingskerswe l (Tunne ) 100 04 GRIP6 Leman St 6&8 Pinchin St E1 100110 GRIP6 Feltham West MCB Level Crossin 100111 GRIP8 South Wales Platform Extensions 100132 GRIP8 ASPRO <£25'k 06/07 South East 100140 GRIP8 Shenfield S&C Renewals 100141 GRIP8 East Kent Area S&C Renewals 100144 GRIP8 Wales & Marshes Stations A2 100 62 GRIP3 Out of London CCTV 100 66 GRIP6 Coldham Lane (O/B Repairs) 100194 GRIP6 Out-of-London CCTV Upgrade 100227 GRIP6 Weymouth Relief Rd - New Bdge 100232 GRIP6 Asbestos Inspections - A648 100268 GRIP6 River Cynon U/B (ABD) 100312 GRIP8 Contaminated Land 100318 GRIP8 Corby: Reinstatment of Passenger Services 100319 GRIP6 Kirkstall Forge and Apperley Bridge New Stations 100320 GRIP1 Radlett Freight Connection 100377 GRIP6 Port of Liverpool Improvements (Olive Mount Chord) 100 82 GRIP4 CMP2/1A Greek Street Strengthening 100392 GRIP6 Old Ends LX renewal 100394 GRIP8 Littleton & Badsey LX & CCTV r 100396 GRIP6 Colthrop & Kintbury LX MCBs - 100400 GRIP8 Onibury & Bromfield MCB LX Ren 100454 GRIP5 Blackthorn 3 100501 GRIP8 Liverpool Lime St. Reta l unit 100507 GRIP6 Victoria Beech Rtl Enhancemnt 100530 GRIP7 UB310/052 Rudha Glas 1 100538 GRIP6 Glenury Viaduct UB133/340 100564 GRIP6 Wembley Centrl Stn (St Modwen) 100606 GRIP8 OLE Campaign Changes 2006-2008 100608 GRIP6 OLE Structure Painting 2006-2008 100621 GRIP6 Newport Station Regeneration 100626 GRIP8 Wes - Capacitor 08/09 - Renewal 100633 GRIP8 LNW - OLE Campaign - Renewal 07/09