High-Energy Neutrino Astrophysics: Status and Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snowmass 2021 Letter of Interest: Ultra-High-Energy Neutrinos

Snowmass 2021 Letter of Interest: Ultra-High-Energy Neutrinos Markus Ahlers,1 Jaime Alvarez-Mu~niz,´ 2 Rafael Alves Batista,3 Luis Anchordoqui,4 Carlos A. Arg¨uelles,5 Jos´e Bazo,6 James Beatty,7 Douglas R. Bergman,8 Dave Besson,9, 10 Stijn Buitink,11 Mauricio Bustamante,1, 12, ∗ Olga Botner,13 Anthony M. Brown,14 Washington Carvalho Jr.,15 Pisin Chen,16 Brian A. Clark,17 Amy Connolly,7 Linda Cremonesi,18 Cosmin Deaconu,19 Valentin Decoene,20 Paul de Jong,21, 22 Sijbrand de Jong,23, 22 Peter B. Denton,24, y Krijn De Vries,25 Michele Doro,26 Michael A. DuVernois,27 Ke Fang,28 Christian Glaser,13 Peter Gorham,29 Claire Gu´epin,30 Allan Hallgren,13 Jordan C. Hanson,31 Tim Huege,32, 11 Martin H. Israel,33 Albrecht Karle,27 Spencer R. Klein,34, 35 Kumiko Kotera,20 Ilya Kravchenko,36 John Krizmanic,30, 37 John G. Learned,29 Olivier Martineau-Huynh,38 Peter M´esz´aros,39 Thomas Meures,27 Miguel A. Mostaf´a,39, 40 Katharine Mulrey,11 Kohta Murase,39, 40, 41 Jiwoo Nam,16 Anna Nelles,42, 43 Eric Oberla,44 Foteini Oikonomou,45 Angela V. Olinto,44 Yasar Onel,46 A. Nepomuk Otte,47 Sergio Palomares-Ruiz,48 Alex Pizzuto,27 Steven Prohira,7 Brian Rauch,49 Mary Hall Reno,46 Juan Rojo,50, 51 Andr´esRomero-Wolf,52 Ibrahim Safa,5, 27 Olaf Scholten,53, 25 Frank G. Schr¨oder,54, 32 Wayne Springer,55 Irene Tamborra,1, 12 Charles Timmermans,51, 23 Diego F. Torres,56 Jo~aoR. -

Neutrino Astrophysics

Neutrino Astrophysics Ryan Nichol UK Input to European Strategy Neutrino Astrophysics Ryan Nichol UK Input to European Strategy Highly cited papers • Higgs Discovery (2012) • Z discovery (1983) –1500+ – 8000+ citations –2000+ • SN1987a neutrinos (1987) • Atmospheric neutrino • Positron excess –1500+ oscillations (1998) [PAMELA] (2008) • Weak neutral current –5000+ citations –1900+ (1973) • Top quark discovery • Reactor neutrino theta_13 –1500+ (1995) (2012) • Charmomium (2003) –3000+ citations –1900+ –1400+ • Solar neutrino oscillations • b-quark discovery (1977) • B-Bbar oscillation (1987) (2002) –1900+ –1300+ –3000+ citations • W-discovery (1983) • nu_mu -> nu_e (2011) • Kaon CP violations (1964) –1800+ –1300+ –3000+ citations • Z width (2005) • Accelerator neutrino • Reactor antineutrino –1700+ oscillation (2002) [KamLAND] (2003) • Proton spin crisis (1989) –1100+ –2000+ citations –1700+ • Muon neutrino discovery • Gravitational Waves • LSND anomaly (2001) (1962) (2016) –1700+ –1100+ –2000+ citations • Parity non conservation • DAMA/Libra (2008-) • c-quark discovery (1974) (1957) –1000+ –2000+ citations –1600+ • Pentaquark [LEPS] (2003) • Solar neutrino • LUX Dark Matter (2013) –1000+ [Homestake] (1968-1998) –1500+ • Neutron EDM (2006) !3 –2000+ • g-2 (2006) –1000+ Highly cited papers • Higgs Discovery (2012) • Z discovery (1983) –1500+ – 8000+ citations –2000+ • SN1987a neutrinos (1987) • Atmospheric neutrino • Positron excess –1500+ oscillations (1998) [PAMELA] (2008) • Weak neutral current –5000+ citations –1900+ (1973) • Top quark -

The Compact Program Booklet

- 1 - MONDAY, 5 SEPTEMBER 2011 WELCOME TO 12th International Conference on Topics in Astroparticle and Underground Physics 5 – 9 September 2011, Munich, Germany - 2 - structure of The ConferenCe SUNDAY, 4 SEP 2011 WEDNesDAY, 7 SEP 2011 Page 11 17:00 - 21:00 Registration/Reception 09:00 - 10:45 Plenary: Neutrinos 11:15 - 13:00 Plenary: Neutrinos MONDAY, 5 SEP 2011 Page 3 14:30 - 16:10 DM AM DBD/NM LE 09:00 - 10:10 Plenary: Cosmology 16:50 - 18:30 DM AM NO C 10:10 - 10:45 Plenary: Dark Matter 20:00 - 23:30 Conference Dinner 11:15 - 11:50 Plenary: Dark Matter 11:50 - 12:25 Plenary: Astrophysical Messengers THURSDAY, 8 SEP 2011 Page 14 12:25 - 13:00 Plenary: Underground Physics 09:00 - 10:45 Plenary: Astrophysical Messengers 14:30 - 16:10 DM AM DBD/NM LE 11:15 - 13:00 Plenary: Astrophysical Messengers 16:50 - 18:30 DM AM NO C 14:30 - 16:10 DM AM DBD/NM GW 16:50 - 18:30 DM LE DBD/NM GW TUesDAY, 6 seP 2011 Page 6 09:00 - 10:50 Plenary: Dark Matter FRIDAY, 9 seP 2011 Page 17 11:15 - 13:00 Plenary: Dark Matter 09:00 - 09:35 Plenary: Underground Physics 14:30 - 16:10 DM AM DBD/NM LE 09:35 - 10:45 Plenary: Astrophysical Messengers 16:50 - 18:30 DM AM NO C 11:15 - 12:25 Plenary: Astrophysical Messengers 18:30 - 20:00 Poster Session 12:25 - 13:00 Concluding Session DM Dark Matter NO Neutrino Oscillations AM Astrophysical Messengers DBD/NM Double Beta Decay, Neutrino Mass C Cosmology LE Low-Energy Neutrinos GW Gravitational Waves - 3 - MONDAY, 5 SEPTEMBER 2011 PLENARY SessION: CosmoloGY I Festsaal 09:00 CMB and Planck Francois Bouchet (IAP Paris) -

Science Case for the Giant Radio Antenna Neutrino Detector

Science Case for the Giant Radio Antenna Neutrino Detector Kumiko Kotera — Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, UMR 7095 - CNRS, Université Pierre & Marie Curie, 98 bis boulevard Arago, 75014, Paris, France ; email: [email protected] “The title [of this book] is more of an expression of hope than a de- scription of the book’s contents [...]. As new ideas (theoretical and experimental) are explored, the observational horizon of neutrino as- trophysics may grow and the successor to this book may take on a different character, perhaps in a time as short as one or two decades.” John N. Bahcall, Neutrino Astrophysics, Cambridge University Press, 1989 igh-energy (> 1015 eV) neutrino as- progress in the fields of high-energy astro- tronomy will probe the working of physics and astroparticle physics. Addi- Hthe most violent phenomena in the tionally, they should contribute to unveil Universe. When most of the information fundamental neutrino properties. we have on the Universe stems from the observation of light, one essential strategy to undertake is to diversify our messengers. 1 Why neutrinos? The most energetic, mysterious and hardly understood astrophysical sources or events Neutrinos are unique messengers that let (fast-rotating neutron stars, supernova ex- us see deeper in objects, further in dis- plosions and remnants, gamma-ray bursts, tance, and pinpoint the exact location of outflows and flares from active galactic nu- their sources. clei, ...) are expected to be producers Neutrinos can escape much denser as- of high-energy non-thermal hadronic emis- trophysical environments than light, hence sion. Hence they should produce copious they enable us to explore processes in the amounts of high-energy neutrinos. -

Pos(ICRC2021)048

ICRC 2021 THE ASTROPARTICLE PHYSICS CONFERENCE ONLINE ICRC 2021Berlin | Germany THE ASTROPARTICLE PHYSICS CONFERENCE th Berlin37 International| Germany Cosmic Ray Conference 12–23 July 2021 Rapporteur ICRC 2021: Neutrinos and Muons PoS(ICRC2021)048 0,1, Anna Nelles ∗ 0DESY, Platanenallee 6, 15738 Zeuthen, Germany 1ECAP, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erwin-Rommel-Str. 1, 91058 Erlangen, Germany E-mail: [email protected] This contribution attempts to summarize the status of the field of neutrinos from the cosmos as presented at the ICRC 2021, the first online-only edition of this conference. This rapporteur report builds on 212 contributions with pre-recorded talks and posters, as well as 11 discussion sessions. Furthermore, many of the session conveners provided valuable input to this summary. 37th International Cosmic Ray Conference (ICRC 2021) July 12th – 23rd, 2021 Online – Berlin, Germany ∗Presenter © Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). https://pos.sissa.it/ Rapporteur: Neutrinos and Muons Anna Nelles The field of neutrino astronomy already provides exciting results, however,it is still dominated by very low statistics in astrophysical neutrino detections. The most transformative results have been discussed in the multi-messenger context [1] and clearly neutrinos are becoming a target of opportunity for all experiments with a potential sensitivity to them. The neutrino field itself is booming with new ideas for detectors and has reached a maturity in which detailed data analysis and systematic detector calibration are the order of business. To summarize the sentiment: the community is doing their homework to get ready for many more neutrinos, which the broader community is excited about. -

Extracting the Energy-Dependent Neutrino-Nucleon Cross Section Above 10 Tev Using Icecube Showers

Extracting the Energy-Dependent Neutrino-Nucleon Cross Section above 10 TeV Using IceCube Showers Bustamante, Mauricio; Connolly, Amy Published in: Physical Review Letters DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.041101 Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Bustamante, M., & Connolly, A. (2019). Extracting the Energy-Dependent Neutrino-Nucleon Cross Section above 10 TeV Using IceCube Showers. Physical Review Letters, 122(4), [041101]. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.041101 Download date: 30. sep.. 2021 PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS 122, 041101 (2019) Extracting the Energy-Dependent Neutrino-Nucleon Cross Section above 10 TeV Using IceCube Showers † Mauricio Bustamante1,2,3,* and Amy Connolly2,3, 1Niels Bohr International Academy & Discovery Centre, Niels Bohr Institute, Blegdamsvej 17, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 2Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics (CCAPP), The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210, USA 3Department of Physics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210, USA (Received 11 January 2018; revised manuscript received 17 November 2018; published 28 January 2019) Neutrinos are key to probing the deep structure of matter and the high-energy Universe. Yet, until recently, their interactions had only been measured at laboratory energies up to about 350 GeV. An opportunity to measure their interactions at higher energies opened up with the detection of high-energy neutrinos in IceCube, partially of astrophysical origin. Scattering off matter inside Earth affects the distribution of their arrival directions—from this, we extract the neutrino-nucleon cross section at energies from 18 TeV to 2 PeV, in four energy bins, in spite of uncertainties in the neutrino flux. -

Aloha VHEPA Participant, Welcome to Hawaii!

Aloha VHEPA participant, Welcome to Hawaii! Thanks a lot for joining the 9th VHEPA workshop. This workshop focuses on future projects to measure very high energy particles and cosmic rays including the NTA (Neutrino Telescope Array) proposal for the Big Island of Hawaii, ANITA, ARA, ARIANNA, AUGER, CTA, GRAND, HAWC, IceCube-Gen 2, JEM-EUSO, KM3NET, and TA. In particular, following the observation of astrophysical neutrinos by IceCube, there is world-wide interest in measuring neutrinos in the energy range above IceCube and below the range covered by Auger, TA and other experiments. Although ANITA observed ultra-high energy cosmic rays, neutrinos in the GZK energy range have not yet been detected either. There are no confirmed point sources of neutrinos or high energy cosmic rays. Best regards, Philip von Doetinchem (chair) Veronica Bindi Tom Browder Peter Gorham Francis Halzen George Hou Tadashi Kifune Jason Kumar John Learned Danny Marfatia Bob Morse Alan Watson Jan Bruce Jacky Li Josie Nanao Meeting location The meeting takes place on the campus of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. East-West Center (EWC) Hawaii Imin International Conference Center Jefferson Hall Pacific room 1777 East-West Road Honolulu, HI 96848 Please find a map with driving and bus directions attached. Parking We will have a limited number of on-campus parking passes on a first-come first-served basis. Parking on campus will be $18 total for three day. More parking is available in the general parking structure (no. 20). Daily parking is only $5. Please find a campus map with the parking structure location attached. -

Ultra-High Energy Neutrinos

XXXVIII International Symposium on Physics in Collision, Bogot´a,Colombia, 11-15 September 2018 Ultra-High Energy Neutrinos James Madsen∗ for the IceCube Collaboration,y Physics Department, University of Wisconsin-River Falls, River Falls, WI USA Abstract Ultra-high energy neutrinos hold promise as cosmic messengers to advance the understanding of extreme astrophysical objects and environments as well as possible probes for discovering new physics. This proceeding describes the motivation for measuring high energy neutrinos. A short summary of the mechanisms for producing high energy neutrinos is provided along with an overview of current and proposed modes of detection. The science reach of the field is also briefly surveyed. As an example of the potential of neutrinos as cosmic messengers, the recent results from an IceCube Collaboration real-time high energy neutrino alert and subsequent search of archival data are described. 1 Introduction Astrophysics has seen an incredible expansion in the last century or so with new ways of viewing the cosmos revealing extreme objects and environments far exceeding what can be reproduced even in the most ambitious particle accelerator facility. High energy astrophysics is an exciting field fueled by advances in the capabilities of observatories across the electromagnetic spectrum and in the size and scope of cosmic ray experiments. Inherently interesting in their own right, astrophysical phenomena also provide a natural source to extend particle physics studies one or more orders of magnitude higher in energy. Cosmic rays and gravity waves were covered in separate talks at this meeting, as were neutrino results from reactors, accelerators, and neutrino-less double beta-decay experiments. -

Highlights in Astroparticle Physics: Muons, Neutrinos, Hadronic

Highlights in astroparticle physics: muons, radiation from any kind of particle acceleration neutrinos, hadronic interactions, exotic par- (Sect. 5). ticles, and dark matter | Rapporteur Talk HE2 & HE3 • Muons are used in a geophysical application for tomography of a volcano (Sect. 6). J.R. H¨orandel • New projects are underway to detect high- energy neutrinos: KM3NeT in the Mediter- ranean Sea, as well as ARA and ARIANNA Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, Radboud on the Antarctic continent (Sect. 7). University Nijmegen, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands | http://particle.astro.ru.nl • First data from the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), in particular from the forward detec- Recent results presented at the International tor LHCf, yield new insight into hadronic in- Cosmic Ray Conference in Beijing will be reviewed. teractions, which are of great importance to de- Topics include HE2: "Muons and Neutrinos" and scribe the development of extensive air showers HE3: "Interactions, Particle Physics Aspects, (Sect. 8). Cosmology". • New upper limits on magnetic monopoles reach sensitivities of the order of keywords: muons, neutrinos, neutrino tele- 10−18 cm−2 s−1 sr−1. Searches for antin- scopes, hadronic interactions, exotic particles, dark uclei indicate that there is less than 1 matter antihelium nucleus per 107 helium nuclei in the Universe (Sect. 9). 1 Introduction • Astrophysical dark matter searches yield up- per limits for the velocity-weighted annihi- The 32nd International Cosmic Ray Conference was lation cross section of the order of hσvi < held in August 2011 in Beijing. About 150 pa- 10−24 cm3 s−1 (Sect. 10). pers were presented in the sessions HE2: "Muons and Neutrinos" and HE3: "Interactions, Particle Physics Aspects, Cosmology". -

NSF Cosmic Frontier Particle Astrophysics Projects

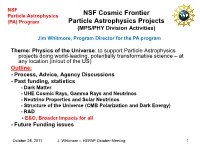

NSF Particle Astrophysics NSF Cosmic Frontier (PA) Program Particle Astrophysics Projects (MPS/PHY Division Activities) Jim Whitmore, Program Director for the PA program Theme: Physics of the Universe: to support Particle Astrophysics projects doing world-leading, potentially transformative science – at any location (in/out of the US) Outline: - Process, Advice, Agency Discussions - Past funding, statistics - Dark Matter - UHE Cosmic Rays, Gamma Rays and Neutrinos - Neutrino Properties and Solar Neutrinos - Structure of the Universe (CMB Polarization and Dark Energy) - R&D - E&O, Broader Impacts for all - Future Funding issues October 28, 2011 J. Whitmore -- HEPAP October Meeting 1 NSF Particle Astrophysics Mathematical and Physical Sciences (PA) Program Directorate OIA (MRI, EPSCoR) OPP MPS PA program OMA October 28, 2011 J. Whitmore -- HEPAP October Meeting 2 NSF Particle Astrophysics PHY – PA (PA) Program Process and Advice We respond to proposals • Different programs (also apply to Particle Physics): – Career – July deadline – PA – Oct 26 target date (Now require Data Management section) – MRI – Jan deadline (internal University competition) • Merit Reviews (email) • Site Visits/Cost, Schedule, & Technical Reviews (for large requests) • FACA Panel (gives advice, 14-15 experts, now in early February) • HEPAP and its sub-panels (PASAG, DMSAG, NUSAG,…) give advice • Also others (ASTRO2010, NAS,…) October 28, 2011 J. Whitmore -- HEPAP October Meeting 3 NSF Particle Astrophysics Discussions with other (PA) Program Agencies • We discuss programs with DOE OHEP & ONP • We discuss projects with other International Agencies • Respect confidentiality – get PI’s permission • International Finance Boards • OECD-GSF-Astrophysics Working Group • Bi-national Discussions (INFN, IN2P3) • Attend Lab Scientific Committee meetings (PACs) October 28, 2011 J. -

On a Prototype Detector for the Radio Emission from Air Showers at the South Pole

Astroteilchenphysik On a prototype detector for the radio emission from air showers at the South Pole DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Fachbereich C { Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften Arbeitsgruppe Prof. Dr. Klaus Helbing Dem Fachbereich Physik vorgelegt von Jan Auffenberg im M¨arz 2010 Contents 1 Introduction 7 2 COSMIC RAYS, NEUTRINOS, AND AIR SHOWERS 9 2.1 Cosmic Ray Particles as Part of the Universe . 9 2.2 CosmicRays................................ 10 2.2.1 Origin of cosmic rays . 10 2.2.2 Acceleration mechanisms of cosmic rays . 12 2.2.3 Propagation mechanism . 13 2.2.4 Energy spectrum of cosmic rays . 14 2.2.5 UHECR sources . 16 2.3 Extensive air showers . 21 2.3.1 Components of extensive air showers . 22 2.4 Radio Emission of Extensive Air Showers . 25 2.4.1 Geo-synchrotron emission . 25 2.4.2 Analytical description of the emission process . 25 2.4.3 Radio emission of CORSIKA simulated air showers . 29 3 ASTROPARTICLE DETECTORS 33 3.1 LOPES . 33 3.1.1 LOPES hardware system . 34 3.1.2 Trigger strategy . 36 3.1.3 LOPES STAR . 36 3.2 IceCube . 37 3.3 RICE and NARC . 40 3.3.1 RICE DAQ . 41 3.3.2 The NARC project AURA . 44 3.3.3 Askaryan Radio Array . 47 3.4 ANITA................................... 48 3 4 CONTENTS 4 RADIO MEASUREMENTS AT THE SOUTH POLE 51 4.1 Radio Background . 51 4.1.1 Continuous background . 51 4.1.2 Transient electromagnetic interferences . 52 4.2 Argentina and South Pole in 2007 . 52 4.3 At the South Pole with RICE in 2008 . -

![Arxiv:1910.11878V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 10 Dec 2020 VII](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6490/arxiv-1910-11878v3-astro-ph-he-10-dec-2020-vii-2986490.webp)

Arxiv:1910.11878V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 10 Dec 2020 VII

MPP-2019-205 Grand Unified Neutrino Spectrum at Earth: Sources and Spectral Components Edoardo Vitagliano,1, 2 Irene Tamborra,3 and Georg Raffelt1 1Max-Planck-Institut f¨urPhysik (Werner-Heisenberg-Institut), F¨ohringerRing 6, 80805 M¨unchen,Germany 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, California, 90095-1547, USA 3Niels Bohr International Academy & DARK, Niels Bohr Institute, Blegdamsvej 17, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark (Dated: October 25, 2019; revised July 4, 2020) We briefly review the dominant neutrino fluxes at Earth from different sources and present the Grand Unified Neutrino Spectrum ranging from meV to PeV energies. For each energy band and source, we discuss both theoretical expectations and experimental data. This compact review should be useful as a brief reference to those interested in neutrino astronomy, fundamental particle physics, dark-matter detection, high-energy astrophysics, geophysics, and other related topics. CONTENTS A. Basic estimate 29 B. Redshift integral 29 I. Introduction2 C. Cosmic core-collapse rate 30 D. Average emission spectrum 32 II. Cosmic Neutrino Background4 E. Flavor Conversion 34 A. Standard properties of the CNB4 F. Detection perspectives 34 B. Neutrinos as hot dark matter5 C. Spectrum at Earth6 X. Atmospheric Neutrinos 35 D. Detection perspectives6 A. Cosmic rays 35 B. Conventional neutrinos 35 III. Neutrinos from Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis7 C. Prompt neutrinos 37 A. Primordial nucleosynthesis7 D. Predictions and observations 37 B. Neutrinos from decaying light isotopes8 E. Experimental facilities 37 C. Neutrinos with mass9 F. Solar atmospheric neutrinos 38 IV. Solar Neutrinos from Nuclear Reactions 10 XI. Extra-terrestrial high energy neutrinos 39 A. The Sun as a neutrino source 10 A.