The Chestnut Oak Forests of the Anthracite Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lvl) Having Different Patterns of Assembly

PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE bioresources.com MECHANICAL PROPERTIES ANALYSIS AND RELIABILITY ASSESSMENT OF LAMINATED VENEER LUMBER (LVL) HAVING DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF ASSEMBLY a,b a, Bing Xue, and Yingcheng Hu * Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) panels made from poplar (Populus ussuriensis Kom.) and birch (Betula platyphylla Suk.) veneers were tested for mechanical properties. The effects of the assembly pattern on the modulus of elasticity (MOE) and modulus of rupture (MOR) of the LVL with vertical load testing were investigated. Three analytical methods were used: composite material mechanics, computer simulation, and static testing. The reliability of the different LVL assembly patterns was assessed using the method of Monte-Carlo. The results showed that the theoretical and ANSYS analysis results of the LVL MOE and MOR were very close to those of the static test results, and the largest proportional error was not greater than 5%. The veneer amount was the same, but the strength and reliability of the LVL made of birch veneers on the top and bottom was much more than the LVL made of poplar veneers. Good assembly patterns can improve the utility value of wood. Keywords: Laminated veneer lumber (LVL); Mechanical properties; Assembly pattern; Reliability; Poplar; Birch Contact information: a: Key Laboratory of Bio-based Material Science and Technology of Ministry of Education of China, College of Material Science and Engineering, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, 150040, China; b: Heilongjiang Institute of Science and Technology, Harbin, 150027, China; * Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Wood is a hard fibrous tissue found in many plants. It has many favorable properties such as its processing ability, physical and mechanical properties, and aesthetics, as well as being environmentally and health friendly. -

Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Figured Wood in Poplar

Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Figured Wood in Poplar Youran Fan1,2, Keith Woeste1,2, Daniel Cassens1, Charles Michler1,2, Daniel Szymanski3, and Richard Meilan1,2 1Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, 2Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, and 3Department of Agronomy; Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract Materials and Methods When “Curly Aspen” (Populus canescens) was first Preliminary Results characterized in the early 1940’s[1], it attracted the attention from the wood-products industry because Genetically engineer commercially 1) Histological sections reveal that “Curly Aspen” has strong “Curly Aspen” produces an attractive veneer as a important trees to form figure. ray flecks (Fig. 10) but this is not likely to be responsible result of its figured wood. Birdseye, fiddleback and for the figure seen. quilt are other examples of figured wood that are 2) Of the 15 SSR primer pairs[6, 7, 8] tested, three have been commercially important[2]. These unusual grain shown to be polymorphic. Others are now being tested. patterns result from changes in cell orientation in Figure 6. Pollen collection. Branches of Figure 7. Pollination. Branches Ultimately, our genetic fingerprinting technique will allow “Curly Aspen” were “forced” to shed collected from a female P. alba us to distinguish “Curly Aspen” from other genotypes. the xylem. Although 50 years have passed since Figure 1. Birdseye in maple. pollen under controlled conditions. growing at Iowa State University’s finding “Curly Aspen”, there is still some question Rotary cut, three-piece book McNay Farm (south of Lucas, IA). 3) 17 jars of female P. alba branches have been pollinated match (origin: North America). -

Chestnut Growers' Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress

This idyllic orchard has benefited from good soil and irrigation. Photo by Tom Saielli Chestnut Growers’ Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress By Elsa Youngsteadt American chestnuts are tough, efficient trees that can reward their growers with several feet of growth per year. They’ll survive and even thrive under a range of conditions, but there are a few deal breakers that guarantee sickly, slow-growing trees. This guide, intended for backyard and small-orchard growers, will help you avoid these fatal mistakes and choose planting sites that will support strong, healthy trees. You’ll know you’ve done well when your chestnuts are still thriving a few years after planting. By then, they’ll be strong enough to withstand many stresses, from drought to a caterpillar outbreak, with much less human help. Soil Soil type is the absolute, number-one consideration when deciding where—or whether—to plant American chestnuts. These trees demand well-drained, acidic soil with a sandy to loamy texture. Permanently wet, basic, or clay soils are out of the question. So spend some time getting to know your dirt before launching a chestnut project. Dig it up, roll it between your fingers, and send in a sample for a soil test. Free tests are available through most state extension programs, and anyone can send a sample to the Penn State Agricultural Analytical Services Lab (which TACF uses) for a small fee. More information can be found at http://agsci.psu.edu/aasl/soil-testing. There are several key factors to look for. The two-foot-long taproot on this four- Acidity year-old root system could not have The ideal pH for American chestnut is 5.5, with an acceptable range developed in shallow soils, suggesting from about 4.5 to 6.5. -

Sample Planting Grids All Chestnuts in the Planting Must Have Permanent Embossed Numerical Tags for That Planting and Will Be Monitored by That Tag

Sample planting grids All chestnuts in the planting must have permanent embossed numerical tags for that planting and will be monitored by that tag. The basic module is 6 x 6 ft spacing with a minimum of 20 ft borders. Such plantings allow easy fencing and mowing. Rows and columns need not be continuous nor do they need to be the same length. Mapping should show gaps. Create a simple schematic map of the planting once done. These configurations can be modified in a wide variety of ways but if lengthened in either direction, a depth of a least 3 rows in any dimension should be maintained. Remember that the pines are an early succession planting designed to create early site coverage and encourage upward growth in hardwoods. Their removal will be a first step in thinning. Different configurations will impose other thinning regimens over time: for example, red oaks might be removed in #1 over time if there is high chestnut survival and vigorous growth. These plantings are designed to introduce at least 30 chestnuts on the site. These should represent at least 2‐3 chestnut families, and may include Kentucky stump sprout families. #1. Alternate row planting 024 ft 30 ft 36 ft 42 ft 48 ft 54 ft 60 ft 66 ft 72 ft 78 ft 98 ft Dimensions 24 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak 110 x 98 ft 10780 sq ft 30 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Chestnut 36 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak Acreage 42 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut -

Big Trees in the Southern Forest Inventory

United States Department of Big Trees in the Southern Agriculture Forest Inventory Forest Service Southern Christopher M. Oswalt, Sonja N. Oswalt, Research Station and Thomas J. Brandeis Research Note SRS–19 March 2010 Abstract or multiple years. Listings of big trees encountered during the most recent forest inventory activities in the South Big trees fascinate people worldwide, inspiring respect, awe, and oftentimes, even controversy. This paper uses a modified version of are reported in this research note and should supplement American Forests’ Big Trees Measuring Guide point system (May 1990) existing lists and registers. to rank trees sampled between January of 1998 and September of 2007 on over 89,000 plots by the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, For more than 75 years, the FIA Program has been charged Forest Inventory and Analysis Program in the Southern United States. Trees were ranked across all States and for each State. There were 1,354,965 by Congress to “make and keep current a comprehensive trees from 12 continental States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands inventory and analysis of the present and prospective sampled. A bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) in Arkansas was the biggest conditions of and requirements for the renewable resources tree (according to the point system) recorded in the South, with a diameter of the forest and rangelands of the United States” of 78.5 inches and a height of 93 feet (total points = 339.615). The tallest tree recorded in the South was a 152-foot tall pecan (Carya illinoinensis) in (McSweeney-McNary Act of May 22, 1928. -

Comparison of Oak and Sugar Maple Distribution and Regeneration in Central Illinois Upland Oak Forests

COmparisON OF OaK AND Sugar MAPLE DistriBUTION AND REGENEratiON IN CEntral ILLINOIS UPLAND OaK FOREsts Peter J. Frey and Scott J. Meiners1 Abstract.—Changes in disturbance frequencies, habitat fragmentation, and other biotic pressures are allowing sugar maple (Acer saccharum) to displace oak (Quercus spp.) in the upland forest understory. The displacement of oaks by sugar maples represents a major management concern throughout the region. We collected seedling microhabitat data from five upland oak forest sites in central Illinois, each differing in age class or silvicultural treatment to determine whether oaks and maples differed in their microhabitat responses to environmental changes. Maples were overall more prevalent in mesic slope and aspect positions. Oaks were associated with lower stand basal area. Both oaks and maples showed significant habitat partitioning, and environmental relationships were consistent across sites. Results suggest that management intensity for oak in upland forests could be based on landscape position. Maple expansion may be reduced by concentrating mechanical treatments in expected areas of maple colonization, while using prescribed fire throughout stands to promote oak regeneration. INTRODUCTION Historically, white oak (Quercus alba) dominated much of the midwestern and eastern U.S. hardwood forests (Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Franklin et al. 1993). Oak is classified as an early successional forest species, and many researchers agree that oak populations were maintained by Native American or lightning-initiated fires (Abrams 2003, Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Hutchinson et al. 2008, Moser et al. 2006, Nowacki and Abrams 2008, Ruffner and Groninger 2006, Shumway et al. 2001). These periodic low to moderate surface fires favored the ecophysiological attributes of oak over those of fire-sensitive, shade-tolerant tree species, thereby continually resetting succession and allowing oaks and other shade-intolerant species to persist in both the canopy and understory (Abrams 2003, Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Crow 1988, Franklin et al. -

Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forest State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forest State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable Mesic Forest (RMF): Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forests are most occurrences of RMF diverse forests in central and eastern in Massachusetts are west Massachusetts where conditions, of the Connecticut River including nutrient richness, support Valley. The presence of Northern Hardwood species mixed with multiple species of species of Oak - Hickory Forests; hickories and oaks in SMOH is a main The herbaceous layer varies from sparse difference between these to intermittent, with sparse spring two types. Broad-leaved ephemerals that may include bloodroot or Woodland-sedge is close trout-lily. Later occurring species may to being an indicator of include wild geranium, herb Robert, wild SMOH. RMF is Rock outcrops in the spring in Sugar Maple - licorice, maidenhair fern, bottlebrush Oak - Hickory Forest area. Photo: Patricia characterized by very Swain, NHESP. grass, and white wood aster. Broad- dense herbaceous growth of spring leaved, semi-evergreen broad-leaved ephemerals; SMOH shares some of the Description: Sugar Maple - Oak - woodland-sedge is close to an indicator of species but with fewer individuals of Hickory Forests occur in or east of the the community. Witch hazel, hepaticas, fewer species. SMOH has evergreen Connecticut River Valley in and wild oats usually occur in transitions ferns, Christmas fern and wood ferns, that Massachusetts. They are associated with to surrounding forest types. RMF lack. Oak - Hickory Forests and outcrops of circumneutral rock and slopes Dry, Rich Oak Forests/Woodlands lack below them that have more nutrients than abundant sugar maple, basswood, and are available in the surrounding forest. -

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin Name Quercus Montana

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin name Quercus Montana Chestnut Oak owes its name to its leaves, 4”-6” long, looking like those of the American Chestnut. It is a species of oak in the white oak group native to eastern U.S. Predominantly a ridge-top tree in hardwood forests. Also called Mountain Oak or Rock Oak because it grows in dry rocky habitats, sometimes even around large rocks. As a consequence of its dry habitat and harsh ridge-top exposure, it is not usually large, 59’–72’ tall; specimens growing in better conditions however can become large, up to 141’. It is a long-lived tree, with high-quality timber when well-formed. The heavy, durable, close-grained wood is used for fence posts, fuel, railroad ties and tannin. Saplings are easier to transplant than many other oaks because the taproot of the seedling disintegrates as the tree grows, and the remaining roots form a dense mat about three feet deep. It is monoecious, having pollen-bearing catkins in mid-spring that fertilize the inconspicuous female flowers on the same tree. It reproduces from seed as well as stump sprouts. The 1”-1-1/2” long acorns mature in one growing season, are among the largest of native American oaks and are a valuable wildlife food. Acorns are produced when a tree grown from seed is about 20 years of age, but sprouts from cut stumps can produce acorns in as little as three years after cutting. Extensive confusion between the chestnut oak (Q. montana) and the swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii) has historically occurred. -

Impact of Structural Defects on the Surface Quality of Hardwood Species Sliced Veneers

applied sciences Article Impact of Structural Defects on the Surface Quality of Hardwood Species Sliced Veneers Vasiliki Kamperidou 1,* , Efstratios Aidinidis 2 and Ioannis Barboutis 1 1 Department of Harvesting and Technology of Forest Products, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 541 24 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Forestry and Natural Environment Management, Agricultural University of Athens, 118 55 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2310998895 Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 7 September 2020; Published: 9 September 2020 Abstract: The surface roughness constitutes one of the most critical properties of wood and wood veneers for their extended utilization, affecting the bonding ability of the veneers with one another in the manufacturing of wood composites, the finishing, coating and preservation processes, and the appearance and texture of the material surface. In this research work, logs of five significant European hardwood species (oak, chestnut, ash, poplar, cherry) of Balkan origin were sliced into decorative veneers. Their surface roughness was examined by applying a stylus tracing method, on typical wood structure areas of each wood species, as well as around the areas of wood defects (knots, decay, annual rings irregularities, etc.), to compare them and assess the impact of the defects on the surface quality of veneers. The chestnut veneers presented the smoothest surfaces, while ash veneers, despite the higher density, recorded the highest roughness. In most of the cases, the roughness was found to be significantly lower around the defects, compared to the typical structure surfaces, probably due to lower porosity, higher density and the presence of tensile wood. -

American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast

American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Nathan A. Daniel June 2012 © 2012 Nathan A. Daniel. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio by NATHAN A. DANIEL has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by James M. Dyer Professor of Geography Brian C. McCarthy Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT DANIEL NATHAN A., M.S., June 2012, Environmental Studies American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio (51 pp.) Directors of Thesis: James M. Dyer and Brian C. McCarthy Restoration of American chestnut (Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh.) is currently underway in eastern North American forests. American chestnut and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr.) trees historically co-occurred in these forests. Today, hemlock-dominated forests are in decline due to hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) infestation, and as such, may serve as appropriate habitat for chestnut reestablishment. To investigate this notion, I evaluated the performance of American chestnut seedlings planted under healthy eastern hemlock-dominated canopies. Two process-oriented greenhouse experiments were also performed to study the response of American chestnut to drought stress and to test the competitive performance of chestnut against red maple (Acer rubrum (L.)), the most abundant hardwood found in the understory of regional hemlock-dominated forests. -

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

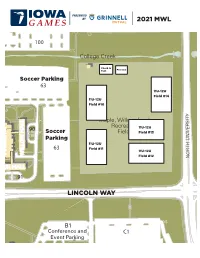

2021 Mwl 2 L

Schilletter - University SCHILLETTER - UNIVERSITY VILLAGE201R COMMUNITY 201B 201D 201N CENTER D A O APPLIED R GOLF COURSE SCIENCE 201P S MAINTENANCE T COMPLEX IV T OFFICE O T LONG ROAD S G DR NBUR IVE 201M BLANK201CE 201K 104 CLUBHOUSE APPLIED D SCIENCE A COMPLEX I O R 201L 102 G 201C APPLIED 103 N O SCIENCE L COMPLEX III APPLIED D SCIENCE 201J A O COMPLEX II 201H R WASTE S T CHEMICAL T 201F D 201G O HANDLING T 101 A S SENSITIVE BUILDING Veenker Memorial Golf Course O INSTRUMENT R FACILITY E LYNN G FUHRER N A LODGE T S 205 201E 201D 201B ISU FAMILY 200 RESOURCE CENTER 205 RIVE 201A BRUNER D Iow ay C reek D A O R L L O H Io C w S ay Cre ek Disc Golf Course 112 L 13 Veenker Memorial Golf Course TH S TRE Furnam Aquatic Center ET EXTENSION 4-H (City Of Ames) T 125 REE YOUTH BUILDING H ST 13T 112 J 124A 112 A 112 J 112 H EH&S ONTARIO STREET 122A ONTARIO STREET SERVICES 120A ROAD STANGE BUILDING 124 FRED115ERIKSEN 112 K 121 BLDG SERVICES COURT ADMINISTRATIVE 112 G HAWTHORN COURT COMMUNITY FREDERIKSEN WANDA DALEY DRIVE DRIVE CENTER COURT 112 K 112 K 122 LIBRARY 120 DOE STORAGE WAREHOUSE FACILITY 119 DOE DOE CONST D 112 D-1 MECH A DOE O R 29 MAINT DOE R PRINTING & E SHOP B ROY J. CARVER PUBLICATIONS31 A CO-LABORATORY BUILDING H 112N 29 NORTH CHILLED 112 B 112 F WATER PLANT ear Creek 112 C 112 D-2 Cl 28 28 Union Pacific Railroad 35 30 27 28A 33 Pammel Woods 12 MOLECULAR 28A FIRE SERVICE BIOLOGY BUILDING COMMUNICATIONS 32 A BUILDING METALS TRANSPORTATION S ADVANCED BUILDING 28A 110 DEVELOPMENT C RUMINANT I 32 TEACHING & HORSE BARN BUILDING T NUTRITION SERVICES E RESEARCH 79 STANGE ROAD STANGE N LAB Cemetery E BUILDING WINLOCK ROAD G LABORATORY MACH ADVANCED LAB SYSTEMS 11W 11E PAMMEL DRIVE NORTH UNIVERSITY BOULEVARD PAMMEL DRIVE SPEDDING WILHELM NATIONAL NATIONAL HYLAND AVENUE HYLAND 11 22 HACH HALL HALL HALL SCIENCE SWINE RSRCH LAB FOR AG.