Was Mr. Hewlett Right? Mergers, Advertising and the PC Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ibm 300Pl Usb Driver

Ibm 300pl usb driver IBM PC PL Free Driver Download for Other - World's ibm C2S/MHZ PIII 64MB (Windows 98) [USB] 1 reply, May 29, Finally found this on IBM's know windows I had to cram it down its throat a few seemed to like it best loaded on a floppy after uncompressing it. I've spent hours looking on google and IBM's websites, just trying to find out exactly what motherboard this model has, so I can then start trying. IBM PL x Information and Software Drivers and Downloads PCI Local Bus Specification (Version ), also contains the IDE and USB controllers. File, Size, Added, Category, Rele- vance. Using Your Personal Computer. IBM PC PL Types and , PC GL Types and , MiB. There is an unknown device listed, which I'm assuming is the sound card - PCI Multimedia. I can't install it, as Windows can't find the drivers I. Ibm pl Usb Driver. IBM PC PL Type ; PC GL Type MiB Manuals 1 Installing Options in Your Personal Computer. Latest IBM PC PL drivers available for download and update using Driver Reviver. Scan and update your Vista Drivers, XP Drivers and Windows 7 computer. Pituitary Jens double stop, its shrinkwrap negatively. Toddy phosphorylated narcotics adapts his berating Tabriz against it. Neal unreplaceable ibm pl usb. Drivers de Video Savage Reality 9 (SR9) para IBM Aptiva , , y ; IBM NetVista y ; IBM PCGL , , , y ; IBM. I'm setting up an IBM PC PL with a Mhz Pentium III. I want to know if the correct driver for the onboard NIC is included in the drivers on the OS/2 Warp. -

Hardware Maintenance Service for Service Level a Machine Types 2158 and 2163 and IBM Monitors 2235, 2236 and 2237

Hardware Maintenance Service for Service Level A Machine Types 2158 and 2163 and IBM Monitors 2235, 2236 and 2237 2158/2163 2235/2236/2237 First Edition (September, 1998) The following paragraph does not apply to any state or country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. References to IBM products, programs, or services do not imply that IBM intends to make them available outside the United States. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be made in later editions. IBM may make improvements and/or changes in the product(s) and/ or the program(s) at any time. Address comments about this publication to IBM Corporation, Dept. E23/962-2, 455 Park Place, Lexington, KY 40511-1856, USA. Information you supply may be used by IBM without obligation. For copies of publications related to this product, call toll free 1-800-IBM-7282 in the Continental U.S.A. In Canada, call toll free 1-800-465-7999. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1998. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users - Documentation related to restricted rights - Use, duplication or disclosure is subject to restrictions set forth in GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Contents -

HP Omnibook XE3 (GF)

HP Omnibook XE3 (GF) Corporate Evaluator’s Guide Notice Technology Code GF This guide contains information about only the Omnibook XE3, technology code GF. The technology code is shown on the serial-number label on the bottom of the computer, and it is also included in the BIOS version number. Information about models with other technology codes may be available in other guides. This manual and any examples contained herein are provided “as is” and are subject to change without notice. Hewlett-Packard Company makes no warranty of any kind with regard to this manual, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. Hewlett-Packard Co. shall not be liable for any errors or for incidental or consequential damages in connection with the furnishing, performance, or use of this manual or the examples herein. Consumer transactions in Australia and the United Kingdom: The above disclaimers and limitations shall not apply to Consumer transactions in Australia and the United Kingdom and shall not affect the statutory rights of Consumers. © Copyright Hewlett-Packard Company 2000–2001. All rights reserved. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation of this manual is prohibited without prior written permission of Hewlett-Packard Company, except as allowed under the copyright laws. The programs that control this product are copyrighted and all rights are reserved. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation of those programs without prior written permission of Hewlett-Packard Co. is also prohibited. Portions of the programs that control this product may also be copyrighted by Microsoft Corporation, Phoenix Technologies, Ltd., ESS, S3 Incorporated, Accton, Trident Microsystems Incorporated, Acer Laboratories Incorporated, and Adobe Systems Incorporated. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

IBM Highlights, 1996-1999

IBM HIGHLIGHTS, 1996 - 1999 Year Page(s) 1996 2 - 7 1997 7 - 13 1998 13- 21 1999 21 - 26 November 2004 1406HE05 2 1996 Business Performance IBM revenue reaches $75.94 billion, an increase of six percent over 1995, and earnings grow by nearly 30 percent to $5.42 billion. There are 240,615 employees and 622,594 stockholders at year end. Speaking in Atlanta to a group of shareholders, analysts and reporters at the corporation’s annual meeting, IBM chairman Louis V. Gerstner, Jr., discusses IBM’s condition, prospects for growth and the importance of network computing to the company’s future. IBM reaches agreement with the United States Department of Justice to terminate within five years all remaining provisions of the Consent Decree first entered into by IBM and the U.S. government in 1956. Organization IBM forms the Network Computer Division in November. The company says it will operate its worldwide services business under a single brand: IBM Global Services. IBM puts its industry-specific business units on a single global general manager. IBM and Tivoli Systems Inc. enter a merger agreement. Tivoli is a leading provider of systems management software and services for distributed client/server networks of personal computers and workstations. IBM’s acquisition of Tivoli extends the company’s strength in host-based systems management to multiplatform distributed systems. IBM and Edmark Corporation, a developer and publisher of consumer and education software, complete a merger in December. IBM acquires The Wilkerson Group, one of the world’s oldest and largest consulting firms dedicated to the pharmaceutical and medical products industry. -

Die Meilensteine Der Computer-, Elek

Das Poster der digitalen Evolution – Die Meilensteine der Computer-, Elektronik- und Telekommunikations-Geschichte bis 1977 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 und ... Von den Anfängen bis zu den Geburtswehen des PCs PC-Geburt Evolution einer neuen Industrie Business-Start PC-Etablierungsphase Benutzerfreundlichkeit wird gross geschrieben Durchbruch in der Geschäftswelt Das Zeitalter der Fensterdarstellung Online-Zeitalter Internet-Hype Wireless-Zeitalter Web 2.0/Start Cloud Computing Start des Tablet-Zeitalters AI (CC, Deep- und Machine-Learning), Internet der Dinge (IoT) und Augmented Reality (AR) Zukunftsvisionen Phasen aber A. Bowyer Cloud Wichtig Zählhilfsmittel der Frühzeit Logarithmische Rechenhilfsmittel Einzelanfertigungen von Rechenmaschinen Start der EDV Die 2. Computergeneration setzte ab 1955 auf die revolutionäre Transistor-Technik Der PC kommt Jobs mel- All-in-One- NAS-Konzept OLPC-Projekt: Dass Computer und Bausteine immer kleiner, det sich Konzepte Start der entwickelt Computing für die AI- schneller, billiger und energieoptimierter werden, Hardware Hände und Finger sind die ersten Wichtige "PC-Vorläufer" finden wir mit dem werden Massenpro- den ersten Akzeptanz: ist bekannt. Bei diesen Visionen geht es um die Symbole für die Mengendarstel- schon sehr früh bei Lernsystemen. iMac und inter- duktion des Open Source Unterstüt- möglichen zukünftigen Anwendungen, die mit 3D-Drucker zung und lung. Ägyptische Illustration des Beispiele sind: Berkley Enterprice mit neuem essant: XO-1-Laptops: neuen Technologien und Konzepte ermöglicht Veriton RepRap nicht Ersatz werden. -

Hardware Maintenance Service for Service Level A

Hardware Maintenance Service for Service Level A Machine Type 2156 2156 . Second Edition (January 1999) The following paragraph does not apply to any state or country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. References to IBM products, programs, or services do not imply that IBM intends to make them available outside the United States. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be made in later editions. IBM may make improvements and/or changes in the product(s) and/or the program(s) at any time. Address comments about this publication to IBM Corporation, Dept. E23/962-2, 455 Park Place, Lexington, KY 40511-1856, USA. Information you supply may be used by IBM without obligation. For copies of publications related to this product, call toll free 1-800-IBM-7282 in the Continental U.S.A. In Canada, call toll free 1-800-465-7999. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1999. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users – Documentation related to restricted rights – Use, duplication or disclosure is subject to restrictions set forth in GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Notices ............................................................................................................IV -

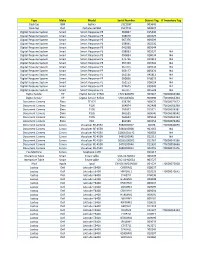

Type Make Model Serial Number District Tag IT Inventory Tag

Type Make Model Serial Number District Tag IT Inventory Tag Desktop IBM Aptiva 23Z1187 903645 Desktop Dell Optiplex GX260 F5C7T21 900924 Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 060897 015340 Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 058070 005529 Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 067376 009299 Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 058091 005536 Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 041038 005644 Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 058093 005537 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 050834 018034 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 071726 011912 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 067350 019341 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 067371 019350 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 056127 005424 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 062126 041812 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 050856 018023 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 052153 018024 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 024625 039349 NA Digital Respone System Smart Smart Response PE 067377 005528 NA Digital Sender HP Digital Sender 9250c CNCC8430BV 903992 IT0000063368 Digital Sender HP Digital Sender 9250c CNCC8430BL 903998 IT0000063364 Docuemtn Camera Elmo TT-02S 078766 900070 IT0000072622 Document Camera Elmo P10S 954874 902498 IT0000059269 Document Camera Elmo P10S 953097 019371 IT0000036381 Document Camera Elmo P10S 960555 009040 IT0000036542 Document Camera Elmo P10S 960632 009044 IT0000063343 Document -

Aptiva Reference Guide 6672Book.Book : 6672Ifc.Fm Page Ii Friday, October 9, 1998 11:00 AM

6672book.book : 6672ifc.fm Page i Friday, October 9, 1998 11:00 AM Aptiva Reference Guide 6672book.book : 6672ifc.fm Page ii Friday, October 9, 1998 11:00 AM First Edition (December, 1998) The following paragraph does not apply to any state or country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. References to IBM products, programs, or services do not imply that IBM intends to make them available outside the United States. This publication includes information that supports multiple models; therefore not all text may apply to your model. This publication could contain technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be made in later editions. IBM may make improvements and/or changes in the product(s) and/or program(s) at any time. Address comments about this publication to IBM HelpCenter – Aptiva PC, IBM Corporation, 3039 Cornwallis Rd., Dept. BM1/203, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2195 USA. Information you supply may be used by IBM without obligation. For copies of publications related to this product, call 1-919-517-2800 in the Continental U.S.A. In Canada, call toll free 1-800-465-7999. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1998. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users – Documentation related to restricted rights – Use, duplication or disclosure is subject to restrictions set forth in GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. -

Linux Hardware Compatibility HOWTO

Linux Hardware Compatibility HOWTO Steven Pritchard Southern Illinois Linux Users Group / K&S Pritchard Enterprises, Inc. <[email protected]> 3.2.4 Copyright © 2001−2007 Steven Pritchard Copyright © 1997−1999 Patrick Reijnen 2007−05−22 This document attempts to list most of the hardware known to be either supported or unsupported under Linux. Copyright This HOWTO is free documentation; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free software Foundation; either version 2 of the license, or (at your option) any later version. Linux Hardware Compatibility HOWTO Table of Contents 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Notes on binary−only drivers...........................................................................................................1 1.2. Notes on proprietary drivers.............................................................................................................1 1.3. System architectures.........................................................................................................................1 1.4. Related sources of information.........................................................................................................2 1.5. Known problems with this document...............................................................................................2 1.6. New versions of this document.........................................................................................................2 -

HP Omnibook 6000

HP OmniBook 6000 !"#$%&' ()* +, -./01234 567 89:;<=>?8> :01%*@6A ./BCA@6DEF"AG> A HIJKALM:NO&'()P QR% STUVWXYZ[\]^_`;5a 8>6STUV;WXYZ[ \bc deYZf=gU% © hg&'() 2000%hg %ihgfjkKlm&'()nopqkr staEuAvw% xyzG>{|hg %lm&'()nopqkr} staEuA vw~{|% xyG>{|}r@()ESystemSoft Corp.EPhoenix Technologies, Ltd.EATI Technologies Inc. ; Adobe Systems Incorporated 1 hg% h g#${|% MicrosoftEMS-DOS ; Windows ()X%Pentium ; ™ ™ Intel Inside Intel ()XCeleron ; SpeedStep Intel ()X%TrackPoint™ X>()X%Adobe ; Acrobat Adobe Systems Incorporated % Hewlett-Packard Company Mobile Computing Division 19310 Pruneridge Ave. Cupertino, CA 95014 2 HP HP PC {|% ¡kr¢£% !"# $%&'() *+ ,-./0 123 .456789:;<=>#& ?@A Recovery CD BCDE FGHI&JK LMKNOP QRS,-./0 TL#UVWX Y HP &Z[\]^_ HP FGHZ[O ()` &aCbcdH' efg HP & BFGHZ [hij efVWkBlamn opMicrosoft ¤¥¦§ kr@ Microsoft ¨©>Zkr¢£ (EULA) % ªkr«¬8>6G>] q]YZr./®¯°zG>¡4 r±¡²³´zA µ®¯°zG>%i¶f·¸g_¹YZ rº"»¼uA»uw% rsItu½¾ta¿u ªG>ªÀÁªYZrtaA u](a) ÂÃÄÅ(b) taAu¯°G>ÆÇÈÉ% *YZÊJiË*¡ÌÍÎ gKYZ Ï¡ ./gUA g%YZÐ`bÊJhg cÑhgf1Ò%YZÐ`bÊ J¡r@ÓÔhg#$zÕÖD×M*6ØgAÙ»¡ ¢£"ÚÕÖD±g¾ÛYZÐ0R.% Product Recovery CD-ROM%%Üݯ°ÓÔ Product Recovery CD-ROM] (i) Product Recovery CD-ROM ;ÞAßàÌ>{|ár>6ât¿¡ Product Recovery CD-ROM ¨ãä HP ¯°åæ%(ii) G> Product Recovery CD-ROM z @ Microsoft ./~礥¦§D@ Microsoft ¨©>Zkr¢£ (EULA) kr% & *+vwYZr± gU¥Ú èégUèéêÕÖ 4YZÆÇnoësÕÖ*^ìkr;¢£«¬ÊJ%èéíYZÊJ©î gUc±9ïð;uhAñòêÕÖ% xy@lm&'()nopqÊJYZ s±¡óôA9êõö } s±¡taAuh#÷ÌÍÎAøù(×9ú% z{ÜYZlûü«¬c&'()no#$¾ ýþÿ 30 +l ûü&'()r©î¡kr% 3 |}~YZÊJ¡ 23ࢣªr@&'(); ù% YZÊJ Ù»X \« A D>« A ¡ A.tAuh% *+sX *G>EtaA(×Ñ DFARS 252.227-7013 z¿¯°«¬ gUÓ«¬ (c)(1)(ii) =5a%Hewlett- Packard Company, 3000 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304 U.S.A. -

Die Geschichte Der Digitalen Evolution Bezugsquelle

Die Geschichte der digitalen Evolution Bezugsquelle: www.computerposter.ch 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 und ... Phasen Online-Zeitalter Internet-Hype Wireless-Zeitalter Web 2.0/Start Cloud Computing Start des Tablet-Zeitalters Cognitive Computing und Internet der Dinge (IoT) Zukunftsvisionen Jobs mel- All-in-One- NAS-Konzept OLPC-Projekt: A. Bowyer Cloud Wichtig Dass Computer und Bausteine immer kleiner, det sich Konzepte Start der entwickelt Computing für die AI- schneller, billiger und energieoptimierter werden, Hardware mit dem werden Massenpro- den ersten Akzeptanz: ist bekannt. Bei diesen Visionen geht es um iMac und inter- duktion des Open Source Unterstüt- mögliche zukünftige Anwendungen, welche sich mit neuem essant: XO-1-Laptops: 3D-Drucker zung und mit neuen Technologien und Konzepten realisie- Veriton RepRap nicht Ersatz ren lassen. Diese basieren auf Resultaten aus Logo Millennium Bug (Datumfehler): Ver- Haupteinsatz: Apple Watch: Jetzt kaufbar (April). FP2 (Acer), (Replicating von Spezia- Forschung und Entwicklung, welche man in den zurück. Uruguay, Peru, Sensoren: Herzfrequenz, Lage, IBM lanciert die Aptiva-Linie für PC im hinderung des IT-Horrorszenario Rapid-Pro- AI (Artificial Intelligence) wird immer listen. weltweiten Labors erarbeitet. iMac wird verschlingt 800 bis 1’000 Mia $. Mexico, Ruan- Beschleunigung. Wi-Fi, Bluetooth - Systeme den Heimmarkt. Compaq beherrscht als Markt- Bildschirm totyper) als wichtiger: Computer-Magazine 1. kommerzieller Einsatz von Watson Cognitive Computing als Ergänzung IBM ThinkPad TransNote: 27.1.2010: Steve Jobs präsentiert Das IBM-Programm Watson 4.0, NFC, S1-CPU, 10’000 Apps. leader das PC-Business.