BASSOON CONCERTOS Mozart | Winter Hummel | Rossini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben Table of Contents Education 2 Relevant Skills 2 Employment Positions Held 2 Performance Experience 3 Collaborative Experience 3 Master Classes 4 Teaching 4 Awards and Recognition 5 International Performances/Foreign Travel 5 Volunteer Work 5 Graduate Degree Recitals 6 Collaborative Repertoire 6 1 BEN SIEBEN [email protected] | 979-479-1197 | 61 San Jacinto St., Bay City, TX, 77414 Education Master of Music in Collaborative Piano 2017 University of Colorado Boulder Primary instructors: Margaret McDonald and Alexandra Nguyen Master of Music in Piano Performance 2012 University of Utah Primary instructor: Heather Conner Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance 2010 Houston Baptist University Primary instructor: Melissa Marse Relevant Skills 25 years of classical piano sight reading improvisation open-score reading transposition jazz and rock styles basso-continuo harpsichord music theory score arranging transcription by ear reading lead sheets keyboard/synthesizer proficiency Italian, German, French, and English diction fluent conversational Spanish Employment Positions Held Emerging Musical Artist-in-Residence, Penn State Altoona 2017 Vocal coach and accompanist for private voice students Graduate Assistant, University of Colorado Boulder 2015-2017 Collaborative pianist, pianist for instrumental students, vocal students, orchestra, opera, and opera scenes classes Choral Accompanist, Texas A&M University 2012-2015 Accompanist for Century Singers and Women’s Chorus Choral Accompanist, Brazos Valley Chorale -

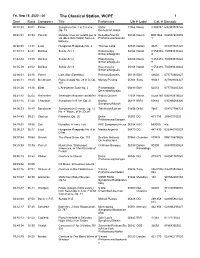

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, Sep 18, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 40:01 Paine Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Ulster 11966 Naxos 8.559747 636943974728 Op. 23 Orchestra/Falletta 00:42:3102:34 Puccini Quando m'en vo' soletta per la Netrebko/Vienna 09185 Decca B001566 028947829478 via (Musetta's Waltz) from La Philharmonic/Noseda 1 boheme 00:46:0513:38 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 Thomas Labe 04785 Dorian 9025 053473025128 01:01:13 42:21 Delibes Sylvia: Act 1 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 01:44:3419:55 Delibes Sylvia: Act 2 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 02:05:59 29:02 Delibes Sylvia: Act 3 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 02:36:0103:10 Ponce Little Star (Estrellita) Perlman/Sanders 00116 EMI 49604 077774960427 02:40:1119:45 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 28 in A, Op. Murray Perahia 05304 Sony 93043 827969304327 101 03:01:2619:16 Bizet L'Arlesienne Suite No. 2 Philharmonia 06499 EMI 62853 077776285320 Orchestra/Karajan 03:21:4205:03 Hoffstetter Serenade (Andante cantabile) Kodaly Quartet 11034 Naxos 8.558180 636943818022 03:27:45 31:38 Chausson Symphony in B flat, Op. 20 Boston 06919 BMG 60683 090266068326 Symphony/Munch 04:00:5316:47 Boccherini Symphony in D minor, Op. 12 Tafelmusik/Lamon 01856 DHM 7867 054727786723 No. 4 "House of the Devil" 04:18:40 09:21 Sibelius Finlandia, Op. 26 Berlin 00365 DG 413 755 28941375520 Philharmonic/Karajan 04:29:0129:56 Suk Pohadka, A Fairy Tale BBC Symphony/Hrusa 06384 BBC MM300 n/a 05:00:2706:17 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

Monday Playlist

February 10, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “I pay no attention whatever to anybody's praise or blame. I simply follow my own feelings.” — WA Mozart Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Elgar The Spanish Lady Suite Guildhall String Ensemble/Salter RCA 7761 07863577612 00:14 Buy Now! Goldmark Sakuntala (Concert Overture), Op. 13 Budapest Philharmonic/Korodi Hungaroton 12552 N/A Trio in B flat for Clarinet, Horn & Piano, 00:32 Buy Now! Reinecke Campbell/Sommerville/Sharon EMI 81309 774718130921 Op. 274 Watkinson/City of London 01:00 Buy Now! Vivaldi Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 4 No. 4 Naxos 8.553323 730099432320 Sinfonia/Kraemer 01:09 Buy Now! Grieg Holberg Suite, Op. 40 English Chamber Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 K. & M. Labeque/Philharmonia 01:31 Buy Now! Bruch Concerto for Two Pianos, Op. 88a Philips 432 095 028943209526 Orchestra/Bychkov Nicolet/Netherlands Chamber 02:01 Buy Now! Bach, C.P.E. Flute Concerto in A minor Philips 442 592 028944259223 Orchestra/Zinman Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 02:26 Buy Now! Mozart Symphony No. 21 in A, K. 134 Philips 422 610 028942250222 Fields/Marriner 02:47 Buy Now! Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind Ensemble Denon 7026 N/A 03:01 Buy Now! Wagner Liebestod ~ Tristan und Isolde Price/Philharmonia/Lewis RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 03:09 Buy Now! Janacek Pohadka (Fairy Tale) Alisa and Vivian Weilerstein EMI Classics 73498 724357349826 03:22 Buy Now! Dvorak Symphony No. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

CONNECTED APART Winter 2021

CONNECTED APART Winter 2021 1 COMPOSE YOUR FUTURE qhere World-class faculty. State-of-the-art facilities you have to see (and hear) to believe. Endless performance and academic possibilities. All within an affordable public university setting ranked the number five college town in America.* Come see for yourself how the University of Iowa School of Music composes futures...one musician at a time. To apply, or for more information, visit music.uiowa.edu. *American Institute for Economic Research, 2017 MUSIC.UIOWA.EDU WINTER 2021 VIRTUAL PERFORMANCES The past year has been difficult for everyone, and we know that for many families, incomes have been reduced or become more unpredictable. To ensure that every CYSO family—no matter their CYSO is investing in the future of music and the financial situation—can enjoy our virtual performances, we've next generation of leaders. We provide music replaced our normal ticketing with a pay-what-you-can donation. education to nearly 800 young musicians ages 6-18 through full and string orchestras, jazz, CYSO virtual winter performances will debut on Saturday, steelpan, chamber music, masterclasses, music March 27, 2021 at 7:00 pm CST. For those who are able, the suggested donation is $40 (the equivalent of $10 per tick- composition and in-school programs. Students et for a family of four) to access all winter performance videos. learn from some of Chicago’s most respected Visit cyso.org/concerts to purchase your tickets. If you cannot professional musicians, perform in the world’s afford a ticket donation at this time, simply fill out the form with a great concert halls, and gain skills necessary for $0 amount to receive the performance link at no charge. -

African-American Bassoonists and Their Representation Within the Classical Music Environment

African-American Bassoonists and Their Representation within the Classical Music Environment D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ian Anthony Bell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Karen Pierson, Advisor Doctor Arved Ashby Professor Katherine Borst Jones Doctor Russel Mikkelson Copyrighted by Ian Anthony Bell 2019 Abstract This paper is the culmination of a research study to gauge the representation of professional African-American orchestral bassoonists. Are they adequately represented? If they are not adequately represented, what is the cause? Within a determined set of parameters, prominent orchestras and opera companies were examined. Of the 342 orchestral and opera companies studied, there are 684 positions for bassoonists. Sixteen of these jobs are currently held by African-Americans. Some of these musicians hold positions in more than one organization reducing the study to twelve black bassoonists. Translated to a percentage, .022% of the professional bassoonists within these groups are African-American, leading the author to believe that the African-American bassoon community is underrepresented in American orchestras and opera companies. This study also contains a biography of each of the twelve bassoonists. In addition, four interviews and five questionnaires were completed by prominent African- American bassoonists. Commonalities were identified, within their lives and backgrounds, illuminating some of the reasons for their success. Interview participants included Rufus Olivier Jr. (San Francisco Opera), Joshua Hood (Charlotte Symphony Orchestra), Monica Ellis (Imani Winds), Alexander Davis (fellowship recipient), and Andrew Brady (Atlanta Symphony Orchestra). -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2017-2018 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2017-2018 Mellon Grand Classics Season March 2 and 4, 2018 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR BENJAMIN GROSVENOR, PIANO SERGEI PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 5, Opus 100 I. Andante II. Allegro moderato III. Adagio IV. Allegro giocoso Mr. Grosvenor Intermission LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Rondo: Molto allegro LEOŠ JANÁČEK Sinfonietta I. Allegretto II. Andante — Allegretto III. Moderato IV. Allegretto V. Andante con moto March 2-4, 2018, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA SERGEI PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 5, Opus 100 (1944) Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontzovka, Russia on April 23, 1891, and died in Moscow on March 5, 1953. He composed his Fifth Symphony in 1944, and it was premiered in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra with Prokofiev conducting on January 13, 1945. The Pittsburgh Symphony premiered the work at Syria Mosque with conductor Fritz Reiner on November 28, 1947, and most recently performed it with Leonard Slatkin on March 24, 2013. The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, E-flat clarinet, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano, harp and strings. Performance time: approximately 46 minutes “In the Fifth Symphony I wanted to sing the praises of the free and happy man — his strength, his generosity and the purity of his soul. I cannot say I chose this theme; it was born in me and had to express itself.” The “man” that Prokofiev invoked in this description of the philosophy embodied in this great Symphony could well have been the composer himself. -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

A Study of Selected Contemporary Compositions for Bassoon by Composers Margi Griebling-Haigh, Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich and Libby

A STUDY OF SELECTED CONTEMPORARY COMPOSITIONS FOR BASSOON BY COMPOSERS MARGI GRIEBLING-HAIGH, ELLEN TAAFFE-ZWILICH AND LIBBY LARSEN by ELIZABETH ROSE PELLEGRINI JENNIFER L. MANN, COMMITTEE CHAIR DON FADER TIMOTHY FEENEY JONATHAN NOFFSINGER THOMAS ROBINSON THEODORE TROST A MANUSCRIPT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the School of Music in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Elizabeth Rose Pellegrini 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In my final DMA recital, I performed Sortilège by Margi Griebling-Haigh (1960), Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra by Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich (1939), and Concert Piece by Libby Larsen (1950). For each of these works, I give a brief biography of the composer and history of the piece. I contacted each of these composers and asked if they would provide further information on their compositional process that was not already available online. I received responses from Margie Griebling-Haigh and Libby Larsen and had to research information for Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich. I assess the contribution of these works to the body of bassoon literature, summarize the history of the literature, discuss the first compositions for bassoon by women, and discuss perceptions of the instrument today. I provide a brief analysis of these works to demonstrate how they contribute to the literature. I also offer comments from Nicolasa Kuster, one of the founders of the Meg Quigley Vivaldi Competition. Her thoughts as an expert in this field offer insight into why these works require our ardent advocacy. ii DEDICATION This manuscript is dedicated, first and foremost, to all the women over the years who have inspired me. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2011 Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra Timothy Patrick Cooper [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Timothy Patrick, "Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/964 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Timothy Patrick Cooper entitled "Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Kenneth A. Jacobs, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Brendan P. McConville, Daniel R. Cloutier Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Concerto For Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Timothy Patrick Cooper August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Timothy Cooper. All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Several individuals deserve credit for their assistance in this project.