7100 SIS 14 13 Van Der Velde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Summary: Srimad-Bhagavatam is compared to the ripened fruit of Vedic knowledge. Also known as the Bhagavata Purana, this multi-volume work elaborates on the pastimes of Lord Krishna and His devotees, and includes detailed descriptions of, among other phenomena, the process of creation and annihilation of the universe. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada considered the translation of the Bhagavatam his life’s work. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non- commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Srimad-Bhagavatam” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com.” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1977-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com. -

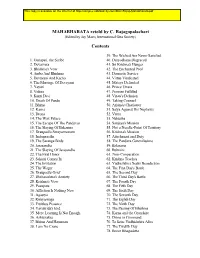

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Krishna Charitrya Manjari” by Rayaru

“Krishna Charitrya Manjari” by Rayaru ´ÉÏ M×üwhÉ cÉÉËU§rÉqÉÇeÉUÏ Krishna Charitra Manjari is a beautiful grantha by Mantralaya Rayaru which gives the essence of entire Krishna Charitre from Bhagavatha and Mahabharatha in 28 shlokaas. Here in each sentence, he has filled it with shastra prameya. It gives many prameyaas like the Vishnu Sarvottamatva, devata taratamya, etc. ÌuÉwhÉÑoÉë¼ÉÌSSåuÉæ: ͤÉÌiÉpÉUWûUhÉå mÉëÉÍjÉïiÉ: mÉëÉSÒUÉxÉÏSè SåuÉYrÉÉÇ lÉÇSlÉÇSÏ ÍzÉzÉÑuÉkÉÌuÉÌWûiÉÉÇ mÉÔiÉlÉÉÇ rÉÉå eÉbÉÉlÉ | EijÉÉlÉÉæixÉÑYrÉMüÉsÉå UjÉcÉUhÉaÉiÉÇ cÉÉxÉÑUÇ mÉÉSbÉÉiÉæ- ¶É¢üÉuÉiÉïÇ cÉ qÉɧÉÉ aÉÑÂËUÌiÉ ÌlÉÌWûiÉÉå pÉÔiÉsÉå xÉÉåsuÉiÉÉlqÉÉlÉç || 1 || Krishna roopa is saakshaat Srimannaarayana roopa, who appeared in bhooloka after being prayed by Brahma rudraadi devataas for the reduction of the burden and weight on the earth due to the presence of adharmic asuric souls. He appeared in the sacred garbha of Devaki-Vasudeva (Kashyapa-aditi) as their eighth son. As per Krishna’s instructions, Vasudeva took him to Gokula, where he gave ananda to Nandagopa – Yashoda. In his early childhood itself, Krishna killed Pootana, who was sent in by Kamsa to kill all the new born children. www.sumadhwaseva.com by Narahari Sumadhwa Page 1 “Krishna Charitrya Manjari” by Rayaru (Udupi Krishna with the alankara of Shakatasura Bhanjana) During upanishkramana period, i.e., at the end of Chaturtha maasa when the birth nakshatra (janma nakshatra) falls, Yashoda had gone for the festival in temple and had kept Krishna under the shade of a cart. Shakatasura who came in the form of a shakata (cart) was killed by Krishna just with the kicking of his mild foot. Another asura Trunavartha who came in the form of wind, lifted Krishna very high in the sky and wanted to throw him down from high in the sky. -

Sri Rukmini Kalyanam Saturday, September 26Th 2015 1:30 PM – 6:00 PM

Hindu Community and Cultural Center 1232 Arrowhead Ave, Livermore, CA 94551 A Non-Profit Organization since 1977 Tax ID# 94-2427126; Inc# D0821589 Shiva-Vishnu Temple Tel: 925-449-6255; Fax: 925-455-0404 Om Namah Shivaya Om Namo Narayanaya Web: http://www.livermoretemple.org Sri Rukmini Kalyanam Saturday, September 26th 2015 1:30 PM – 6:00 PM Vasudeva Sutham Devam Kamsa Chaanoora Mardhanam Devaki Paramaanandham Krishnam Vande' Jagathgurum Sri Rukmini Kalyanam is a very auspicious and sacred event planned for the first time on Saturday, September 26th 2015 at Shiva Vishnu Temple. Rukmini is the incarnation Goddess Lakshmi for pairing with Lord Krishna who is incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Rukmi, the brother of Rukmini, tries to get her married to Sisupala. Rukmini writes to Lord Krishna and sends the letter through a brahmin priest. Lord Krishna rushes to fetch Rukmini and takes her to Dwaraka by defeating all the kings. It is a practice in hindu families to make unmarried girls/boys recite, listen, perform or witness Rukmini kalyanam so that marriage gets settled soon. Also they believe that power of recital can make them get suitable spouses. Please plan on participating in this auspicious event and receive divine blessings Event Schedule 1:30 PM Rukmini Kalyana Ghattam - Parayanam 3:00 PM Edurukolu Utsavam 3:30 PM Unjal Seva 4:00 PM Kalyanotsavam 6:00 PM Theertha Prasadam and Kalyana Bhojanam for all devotees Instagram.com/livermoretemple facebook.com/livermoretemple twitter.com/livermoretemple Hindu Community and Cultural Center 1232 Arrowhead Ave, Livermore, CA 94551 A Non-Profit Organization since 1977 Tax ID# 94-2427126; Inc# D0821589 Shiva-Vishnu Temple Tel: 925-449-6255; Fax: 925-455-0404 Om Namah Shivaya Om Namo Narayanaya Web: http://www.livermoretemple.org Sri Rukmini Kalyanam - Significance Sri Rukmini Kalyanam has great religious significance. -

Secrets of Srimad Bhagavad Gita Revealed

Secrets of Srimad Bhagavad Gita Revealed Introduction The Bhagavad Gita, the greatest devotional book of Hinduism, has long been recognized as one of the world’s spiritual classics and a guide to all on the path of Truth. The land of the Vedas and the Upanishads – that is India. India has a rich culture of respecting the Father, Mother, Elders and Teachers. The influence of Western Culture and the glitz of Materialism is misleading the children of India and corrupting the society by compromising the values. This is an attempt to lead the people in the right direction. Let us read the mantra from Yajur Veda (36-24) and understand the deep meaning and spiritual significance it upholds. Let us live long. Without depending on anyone. I am deeply pained by the children over speeding for the thrill on the streets of India. The immaturity of some children is evident with their utter disregard to their self well-being when they forget that “Speed Thrills, But also Kills”. Some other children want to depend their entire lives on the hard work of their parents. Let us take Vedas as an example of how we need to live our lives. Let us make a firm resolve to lead Young India by example with the inspiration of Swami Vivekananda. Let us make a firm resolve to lead the Future generations of Young India with the inspiration provided by the teachings of Lord Krishna in Bhagavad Gita. Let us learn to take good care of ourselves. TACHCHA KSHURDEVHITAM PURASTACHRUKRAMMUCHARAT PASHYEM SHARADAHA SHATAM JIVEMA SHRADAHA SHATAM SHRUNUYAMA SHARADAHA SHATAM PRA BRAYAMA SHARADAHA SHATMADINAHA SYAM SHARADAHA SHATAM BHUYASHCHA SHARADAHA SHATAM BHUYASHCHA SHARADAHA SHATATA -------------(36/24, Yajurveda) He first arose who was the doer of good to the scholars and was blessed with pure eyes of knowledge. -

Lord Krishna – Childhood Stories

Lord Krishna – Childhood Stories Lord Krishna‟s life is associated with a lot of interesting & instructive events. He is one of the most popular divine heroes. Here are a few interesting tales associated with Krishna‟s life: The Story of Krishna & Putana Kansa, the evil uncle of Krishna had told Putana-the female demon, to kill baby Krishna. Putana disguised herself as a cowherdess & went to Gokul. After killing many babies by feeding them with her poisoned milk, she entered Krishna‟ house. Krishna knew her real form . He sucked so hard that he extracted Putana‟s life along with the milk.Before dying ,Putana assumed her original form & died. The Gopis with Rohini and Yasoda came rushing to the spot and took up the child, which was playing fearlessly on the body of Putana who was freed from her sins as she had offered to give milk to the Lord. So no matter how powerful evil is, it always gets defeated by the Good. Kindergarten – Krishna Childhood Stories Page 1of 17 Overturning of the Cart The ceremony observed on the child being able to stand on his legs, and the birthday ceremony was observed together. There was a great feast at the house of Nanda. After completion of the bath, Yasoda found that her child closed His eyes in sleep and so she put Him to bed under a cart which contained vessels full of milk and curd. After some time, the child opened His eyes and cried for His milk. As Yasoda was busily engaged in receiving her guests, she did not hear Sri Krishna‟s cry. -

Conversation with Lord Krishna

Conversation with Lord Krishna Conversation with Lord Krishna Dr. Varanasi Ramabrahmam Worldwide Circulation through Authorspress Global Network First Published in 2017 by Authorspress Q-2A Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi-110 016 (India) Phone: (0) 9818049852 e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.authorspressbooks.com Conversation with Lord Krishna ISBN 978-93-5207-***-* Copyright © 2017 Varanasi Ramabrahmam Disclaimer This is a work of fiction. The characters and events are entirely imaginary and the names are fictitious and no personal reflections of any kind are intended. Any resemblance to any person, living or dead, is purely coincidental. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the express written consent of the author. Printed in India at Krishna Offset, Shahdara Preface न देवो वयते काठे न पाषाणे न मृमये। भावेषु वयते देवः तमात ् भावो ह कारणम ्॥ Na devo vidyate kaashthe Na paashaane na mrunmaye Bhaaveshu vidyate devah Tasmaat bhaavo hi kaaranam The Lord lives not in the wooden carving Nor in the sculpture made of stone or clay; The Lord lives in our thoughts And it is through our thoughts that we see him; Dwell in everything, Everywhere, always Introduction Lord Krishna is the eighth incarnation, manifestation (avatara) of Lord Maha Vishnu. Lord Krishna is most beloved God and friend of many Indians. His birth, pranks at Brindavan, Love and courtship with Radha and other gopikas (cow-herd girls), -

Lord Krishna-The Jagat Guru

[Draw your reader in with an engaging abstract. It is typically a short summary of the document. When you’re ready to add your content, just click here and start typing.] Lord Krishna- the Jagat Guru K Sriram Sri Ramana Bhaktha Samajam Chennai Lord Krishna– The Jagat Guru [Loka Maha Guru] Devaki Paramanandam Vasudeva sudam Devam Kamsa Chanoora MardanamI Devaki Paramanandam Sri krishnam vande Jagat GurumII The One who was born to Vasudeva, the One who annihilated Kamsa & Chanoora, the One whose very name plunges his mother Devaki into ecstacy, To Him, the Loka Maha Guru, Lord Krishna, I pay my humble obeisance. Page 1 of 9 Introduction It is surprising to note that Lord Krishna’s life represents the average person of today. Brought up in a lower middle class family, the small boy spends his entire time in his studies under very trying circumstances. Higher studies take him to the cities and even overseas. His circumstances change totally when he converts his Knowledge into Experience. Experience takes him to corridors of Power which, again, lands him in a completely different atmosphere. His later days don’t even remotely resemble his childhood days. He could hardly return to his native village which was his dwelling place as a child. Finally, he leaves the world as a loner in yet another totally different atmosphere. Lord Krishna’s life exactly corresponds to such a life of an average person today in spite of the fact that 5000 years have elapsed since his appearance on this planet. He was brought up in a cowherd’s family as a child. -

Krishna's Life-Story in Bengali Scrolls: Exploring the Invitation to Unroll

72 73 4 Krishna’s Life-Story in Bengali Scrolls: Exploring The Invitation to Unroll PIKA GHOSH HAVERFORD COLLEGE 74 Pika Ghosh Krishna’s Life-Story in Bengali Scrolls: Exploring The Invitation to Unroll 75 Fig. 4.1. Narrative hand-scrolls (pata) have been assembled scroll to another, and one session to the next. The coordination of verbal and bodily components Krishnalila (Play of Krishna) Scroll, and painted by the painter-minstrel (patua) with the framed scenes of images can generate distinctive interpretations. A singer may recognise Medinipur District communities of Bengal to tell stories for at least two particular visual properties in a sequence of images or consonances between verse and picture, while (nineteenth- 1 century). Opaque hundred years. Such itinerant bards have traditionally unfurling the scenes for an audience; bolder or more skilled practitioners may choose to explore watercolor on paper. Stella employed the picture sequences to sing well-known these through particular inflections of voice or gesture of hand. Such relationships can turn on Kramrisch stories from the lives of deities (fig. 4.1) and saints, the repetition or variation of colour and compositional choices, which may be underscored by the Collection, Philadelphia the epics, and more recently to address contemporary guiding finger, emphasised or subverted by the words sung. Some patua are charismatic entertainers Museum of Art, social issues and political events.2 with powerful singing voices who fill performance venues and mesmerise audiences, offering Philadelphia, Accession no: 1994- These scrolls have a distinctive vertical format of interpretive nuance through skillful manipulation of the lyrics, intonation, rhythm, and tempo. -

Essence of Shrimad Bhagavad Gita

1 ESSENCE OF BHAGAVAD GITA Translated and interpreted byV.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, now at Chennai 1 2 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda- Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ -Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad; Essence of Maitri Upanishad Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students Essence of Narada