Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vitality of Quebec's English-Speaking Communities: from Myth to Reality

SENATE SÉNAT CANADA THE VITALITY OF QUEBEC’S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: FROM MYTH TO REALITY Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages The Honourable Maria Chaput, Chair The Honourable Andrée Champagne, P.C., Deputy Chair October 2011 (first published in March 2011) For more information please contact us by email: [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-0088 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: Senate Committee on Official Languages The Senate of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: http://senate-senat.ca/ol-lo-e.asp Ce rapport est également disponible en français. Top photo on cover: courtesy of Morrin Centre CONTENTS Page MEMBERS ORDER OF REFERENCE PREFACE INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 QUEBEC‘S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: A SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE ........................................................... 4 QUEBEC‘S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: CHALLENGES AND SUCCESS STORIES ...................................................... 11 A. Community life ............................................................................. 11 1. Vitality: identity, inclusion and sense of belonging ......................... 11 2. Relationship with the Francophone majority ................................. 12 3. Regional diversity ..................................................................... 14 4. Government support for community organizations and delivery of services to the communities ................................ -

Natural Phonetic Tendencies and Social Meaning: Exploring the Allophonic Raising Split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly

This is a repository copy of Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133952/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, E.F. and Carter, P. (2018) Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. Language Variation and Change, 30 (3). pp. 337-360. ISSN 0954-3945 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157 This article has been published in a revised form in Language Variation and Change [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Title: Natural phonetic tendencies -

The Loyalist Origins of Canada's Identity Crisis

Condemned to Rootlessness: The Loyalist Origins of Canada's Identity Crisis Introduction In the view of the English-speaking Canadian media, Canada has an identity crisis, a situation attributable to divisions within the Canadian body politic that are regularly expressed in constitutional bickering between Quebec and the Rest of Canada and between the provinces and the federal government.1 Yet the identity crisis in the lifeworld of the average English-Canadian appears to possess a somewhat different quality. The following statement from Rod Lamirand, a resident of Surrey, B.C., expresses the subjectivity of this existential unease with remarkable accuracy: 'We [our family] were isolated, self-sufficient, cut off from a close community and from our pasts...Our family was not drawn into a neighborhood of friends because of a shared difference from mainstream society. We didn't have a name for the cultural majority because for the most part they were us. We were part of the dominant cultural society and we had no real culture. The great wash of pale European blood that saturated this continent was uniform in color only. Much of what survived is a hodgepodge of eclectic, meaningless routines...We were the product of white bread and instant coffee, Hollywood and the CBC....'2 (emphasis added) The connection between the Canadian identity crisis mentioned in the English-Canadian media and Lamirand's statement might appear distant. Surely, one might ask, the latter reflects a problem that should be labeled 'English-Canadian' rather than 'Canadian.' It is the position of this paper, however, that the discourses of English-Canadian and Canadian identity are inextricably bound. -

Community Development in English-Speaking Communities in Québec: Lessons Learned from a Participatory Action Research Project

Community development in English-speaking communities in Québec: lessons learned from a participatory action research project INSTITUT NATIONAL DE SANTÉ PUBLIQUE DU QUÉBEC Community development in English-speaking communities in Québec: lessons learned from a participatory action research project Développement des individus et des communautés January 2014 AUTHORS Mary Richardson, PhD, Anthropologist Institut national de santé publique du Québec Shirley Jobson, research professional Institut national de santé publique du Québec Joëlle Gauvin-Racine, research professional Institut national de santé publique du Québec REVIEW COMMITTEE Cheryl Gosselin, Professor Bishop’s University Jennifer Johnson, Executive Director Community Health and Social Services Network Kit Malo Centre for Community Organizations Lorraine O’Donnell Québec English-Speaking Communities Research Network (Concordia University and Canadian Institute for Research on Linguistic Minorities) Louis Poirier, Chef d’unité Institut national de santé publique du Québec Paule Simard, Chercheure Institut national de santé publique du Québec Normand Trempe, Project coordinator Institut national de santé publique du Québec ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was instigated by the Community Health and Social Services Network (CHSSN) and received financial support from Health Canada. We also wish to acknowledge the valuable comments and suggestions made by the review committee. Ce document est disponible intégralement en format électronique (PDF) sur le site Web de l’Institut national de santé publique du Québec au : http://www.inspq.qc.ca. Les reproductions à des fins d’étude privée ou de recherche sont autorisées en vertu de l’article 29 de la Loi sur le droit d’auteur. Toute autre utilisation doit faire l’objet d’une autorisation du gouvernement du Québec qui détient les droits exclusifs de propriété intellectuelle sur ce document. -

The Case of the Second Person Plural Form Memòria D’ Investigació

Pronominal variation in Southeast Asian Englishes: the case of the second person plural form Memòria d’ investigació Autora: Eva María Vives Centelles Directora: Cristina Suárez Gómez Departament de Filologia Espanyola, Moderna i Clàssica Universitat de les Illes Balears Data 10 Gener 2014 OUTLINE 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………...........2 2. Brief history of World Englishes ……………………………………............4 3. Theoretical framework: Models of analysis………………………………...6 3.1 Kachru’s Three Concentric Circles……………………………..7 3.2.McArthur’s Circle of World English…………………………..10 3.3.Görlach’s A circle of International English…………………….12 3.4.Schneider’s Dynamic Model of Postcolonial Englishes……….14 4. East and South-East Asian Englishes………………………………………25 4.1. Indian English (IndE) .…………………………………………26 4.2. Hong Kong English (HKE)…………………………………….34 4.3 Singapore English (SingE)……………………………………...38 4.4. The Philippines English (PhilE)………………………………44 5. Second person plural forms in the English language……………………....48 6. Description of the corpus and data analysis……………………………….58 6.1. Description of the corpus………………………………………58 6.2. Data Analysis…………………………………………………..61 7. Conclusions……………………………………………………...................80 8. Limitations of the study…………………………………………………….84 9. Questions for further research……………………………………………...84 10. References.....................................................................................................85 11. Appendix…………………………………………………………………...93 1 1. INTRODUCTION When the American president John Adams (1735-1826) -

Caribbean English As a Challenge to Lexicography

Richard Allsopp CARIBBEAN ENGLISH AS A CHALLENGE TO LEXICOGRAPHY Introduction Almost as soon as the English throne finally broke with Catholicism, with the accession of Elizabeth I, one of her seamen, John Hawkins, sometime treasurer of her Royal Navy, began slave trading in defiance of Spain, and, in 1562, "got into his possession" at Sierra Leona (sic, from Hakluyt as cited in Payne 1907:7) "the number of 300 Negros at least" and sailed to the north coast of Hispaniola (Haiti) where he "made vent of the whole number of his Negros". Buying, transporting and selling slaves took easily 9 months (the 'triangular trade' took a year); but even if the migrated Africans would not have retained many English words from the ship's crew in this first venture - which Hawkins repeated on a much more wide-ranging Caribbean scale in one of Elizabeth's own ships (the Jesus of Lubeck) in 1564/65 - it is historically true that the English language had begun making substantial thrusts from Plymouth to the West Indies and South America long before it did so to North America. It was seamen's English that brought Protestantism's'mailed fist into the rich belly of the New World, as the logical forerunner of the religious hands that guided the Mayflower to North America some half a century later in 1620. If this sounds exaggerated one need only recall that Sir Francis Drake's great plundering armada of 25 ships sailed in 1585 on what is historically known as 'Drake's West Indian Voyage', and a hazardous channel in the Virgin Islands is still known today as 'Drake's Passage'. -

Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: a 21St Century Perspective

MULTILINGUAL MATTERS 116 Series Editor: John Edwards Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective Edited by Joshua A. Fishman MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective/Edited by Joshua A. Fishman. Multilingual Matters: 116 Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Language attrition. I. Fishman, Joshua A. II. Multilingual Matters (Series): 116 P40.5.L28 C36 2000 306.4’4–dc21 00-024283 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1-85359-493-8 (hbk) ISBN 1-85359-492-X (pbk) Multilingual Matters Ltd UK: Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon BS21 7HH. USA: UTP, 2250 Military Road, Tonawanda, NY 14150, USA. Canada: UTP, 5201 Dufferin Street, North York, Ontario M3H 5T8, Canada. Australia: P.O. Box 586, Artarmon, NSW, Australia. Copyright © 2001 Joshua A. Fishman and the authors of individual chapters. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Index compiled by Meg Davies (Society of Indexers). Typeset by Archetype-IT Ltd (http://www.archetype-it.com). Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd. In memory of Charles A. Ferguson 1921–1998 thanks to whom sociolinguistics became both an intellectual and a moral quest Contents Contributors . vii Preface . xii 1 Why is it so Hard to Save a Threatened Language? J.A. -

1 Separatism in Quebec

1 Separatism in Quebec: Off the Agenda but Not Off the Minds of Francophones An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Politics in Partial Fulfillment of the Honors Program By Sarah Weber 5/6/15 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 3 Chapter 2. 4 Chapter 3. 17 Chapter 4. 36 Chapter 5. 41 Chapter 6. 50 Chapter 7. Conclusion 65 3 Chapter 1: Introduction-The Future of Quebec The Quebec separatist movement has been debated for decades and yet no one can seem to come to a conclusion regarding what the future of the province holds for the Quebecers. This thesis aims to look at the reasons for the Quebec separatist movement occurring in the past as well as its steady level of support. Ultimately, there is a split within the recent literature in Quebec, regarding those who believe that independence is off the political agenda and those who think it is back on the agenda. This thesis looks at public opinion polls, and electoral returns, to find that the independence movement is ultimately off the political agenda as of the April 2014 election, but continues to be supported in Quebec public opinion. I will first be analyzing the history of Quebec as well as the theories other social scientists have put forward regarding separatist and nationalist movements in general. Next I will be analyzing the history of Quebec in order to understand why the Quebec separatist movement came about. I will then look at election data from 1995-2012 in order to identify the level of electoral support for separatism as indicated by the vote for the Parti Quebecois (PQ). -

French Influence in Canadian English from the 18Th Century: from Words to Sounds? Julie Rouaud

French Influence in Canadian English from the 18th century: from words to sounds? Julie Rouaud To cite this version: Julie Rouaud. French Influence in Canadian English from the 18th century: from words to sounds?. 12e colloque international PAC, Sep 2016, Aix-en-Provence, France. hal-01936077 HAL Id: hal-01936077 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01936077 Submitted on 27 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. French Influence in Canadian English from the 18th century: from words to sounds? Julie Rouaud [email protected] Introduction: What is Canadian English? Canadian English is often described as: • Relatively homogeneous variety of English (Josselin-Leray, Durand, Lopez, 2015). • 2 sets of linguistic norms: similar to General American (e.g. rhotic variety), while retaining some British English features (e.g. suffix –ile [ail] unlike General American [Əl] in words like fragile). However Canadian English also has its specificity: • The linguistic situation in Canada has been complex from the 18th century (see map): • Built on colonization and immigration in addition to indigenous people. • Unique contacts between French and English facilitating linguistic interactions and mutual influence until now. -

Newfoundland English

Izaro Zalacain Mendia Degree in English Studies 2019-2020 NEWFOUNDLAND ENGLISH Supervisor: Miren Alazne Landa Departamento de Filología Inglesa, Alemana y de Traducción e Interpretación Área de Filología Inglesa Abstract The English language has undergone many variations, leaving uncountable dialects in every nook and cranny of the world. Located at the north-east of Canada, the island of Newfoundland presents one of those dialects. However, within the many varieties the English language features, Newfoundland English (NE) remains as one of the less researched dialects in North America. The aim of this paper is to provide a characterisation of NE. In order to do so, this paper focuses on research questions on the origins of the dialect, potential variation within NE, the languages it has been in contact with, its particular linguistic features and the role of linguistic distinction in the Newfoundlander identity. Thus, in this paper I firstly assess the origins of NE, which are documented to mainly derive from West Country, England, and south-eastern Ireland, and I also provide an overview of the main historical events that have influenced the language. Secondly, I show the linguistic variation NE features, thus displaying the multiple dialectal areas that are found in the island. Furthermore, I discuss the different languages that have been in contact with the variety, namely, Irish Gaelic and Micmac, among others. Thirdly, I present a variety of linguistic features of NE -both phonetic and morphosyntactic- that distinguish the dialect from the rest of North American varieties, including Canadian English. Finally, I tackle the issue of language and identity and uncover a number of innovations and purposeful uses of certain features that the islanders show in their speech for the sake of identity marking. -

Community Education and Development: Perspectives on Employment, Employability and Development of English-Speaking Black Minority of Quebec

Special Issue 2019, Article 1 from Series of 5 (Editorial) Collaborative Unity and Existential Responsibility COMMUNITY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT: PERSPECTIVES ON EMPLOYMENT, EMPLOYABILITY AND DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH-SPEAKING BLACK MINORITY OF QUEBEC Clarence S Bayne* Director of ICED , John Molson [email protected] School of Business, Concordia Uni- versity, President of BCRC * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Background On December 7, 2018, the Black Community Forum of Montreal held a conference on “Community Education and Development: perspectives on English-Speaking Blacks and Other Minorities”. The IJCDMS Journal has selected a number of the conference papers for publication in its Special Conference Series: “Collaborative Unity and Existential Responsi- bility.” This article serves as an overview to the conference; and provides a theoretical framework against which the reader can derive a better under- standing of those papers. It allows the reader to reflect meaningfully on the optimality of the decision search rules adopted by various cultural subgroups, by comparing them to the behaviors of successful agent types in the computer simulated studies discussed in this paper. The targeted cultural sub-populations are the English-Speaking Blacks in Montreal. method of lecturing to cater for the next generation of learners. Framework and The overall research approach used is based on critical realism. We postu- approach late that patterns in the responses of leadership in a social dynamic system may be impacted by values and uncertain events that are better explained by using a qualitative system analysis as opposed to traditional quantitative analyses based on positivist assumptions. We consider Montreal and Que- bec societies diverse complex adaptive systems generating outcomes, not always predictable, in environments that vary from very hospitable to in- Accepting Editor: Raafat George Saadé│ Received: February 14, 2019 │ Revised: March 23 & June 24, 2019│Accepted: July 19, 2019 Cite as: Bayne, C. -

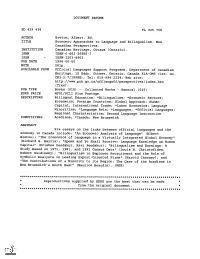

Economic Approaches to Language and Bilingualism. New AVAILABLE

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 438 FL 025 708 AUTHOR Breton, Albert, Ed. TITLE Economic Approaches to Language and Bilingualism. New Canadian Perspectives. INSTITUTION Canadian Heritage, Ottawa (Ontario). ISBN ISBN-0-662-26885-7 ISSN ISSN-1203-8903 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 261p. AVAILABLE FROM Official Languages Support Programs, Department of Canadian Heritage, 15 Eddy, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A-0M5 (Cat. no. CH3-2-7/1998E); Tel: 819-994-2224; Web site: http://www.pch.gc.ca/offlangoff/perspectives/index.htm (free). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bilingual Education; *Bilingualism; *Economic Factors; Economics; Foreign Countries; Global Approach; Human Capital; International Trade; *Labor Economics; Language Minorities; *Language Role; *Languages; *Official Languages; Regional Characteristics; Second Language Instruction IDENTIFIERS Acadians; *Canada; New Brunswick ABSTRACT Six essays on the links between official languages and the economy in Canada include: "An Economic Analysis of Language" (Albert Breton); "The Economics of Language in a Virtually Integrated Global Economy" (Richard G. Harris); "Speak and Ye Shall Receive: Language Knowledgeas Human Capital" (Krishna Pendakur, Ravi Pendakur); "Bilingualism and Earnings: A Study Based on 1971, 1981, and 1991 Census Data" (Louis N. Christofides, Robert Swidinsky); "Bilingualism in Employee Recruitment and the Role of Symbolic Analysts in Leading Export-Oriented Firms" (Harold Chorney); and "The Contributions of a Minority to its Region: The Case of the Acadians in New Brunswick's South East" (Maurice Beaudin).(MSE) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** oo en -cr o. A 110 A ISIS MIK MINIM AAs IA 1- .