Putting Archival Audiovisual Media Into Context: an Archival Approach to Processing Mixed-Media Manuscript Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of a Preservation Needs Assessment Executive Summary

Report of a Preservation Needs Assessment Wrentham Historical Commission Wrentham, MA March 29, 2018 Submitted on June 8, 2018 Sean Ferguson Preservation Specialist Northeast Document Conservation Center 100 Brickstone Square Andover, MA 01810 978.470.1010 [email protected] Executive Summary Paper-based, audiovisual and photographic materials housed in the Old Fiske Library Museum of the Wrentham Historical Commission (WHC) were assessed for preservation planning purposes by Sean Ferguson, Preservation Specialist for the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) in Wrentham, MA on March 29, 2018. Simmons College graduate student Lauren Hansen joined the assessment as an educational opportunity and observed and took part in the assessment. The assessment evaluated the buildings and environments as they relate to the preservation needs of the materials; examined current policies, storage, and handling procedures; and assessed the general condition of materials. Observations and recommendations are based on a pre-site visit questionnaire, a full-day site visit, and discussions with Chairman Greg Stahl, Vice Chairman Leo Baldyga, Treasurer and Secretary Susan Harris, Members Marion Cafferky, William Keyes, Alex Leonard, Kim Shipala, and Volunteer Cheri Leonard. Wrentham Historical Commission was established on March 27, 1967 and is responsible the stewardship and exhibition of Wrentham’s history. To these ends, WHC maintains an archives of historical materials and artifacts, manages the circa 1740’s Wampum House, and operates a plaque program to mark locations of historical significance in the Town. In 2010, WHC renovated the Old Fiske Museum, which was formally the town library, to make it suitable for the storage of historical collections. Following the renovation, the Commission relocated nearly all its historical collections into the Museum. -

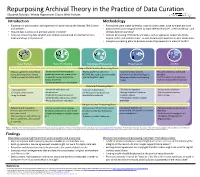

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation Elizabeth Rolando| Wendy Hagenmaier |Susan Wells Parham Introduction Methodology • Expansion of data curation and digital archiving services at the Georgia Tech Library • Process the same digital collection, once by data curator, once by digital archivist and Archives. • Data curation processing informed by OAIS Reference Model1, ICPSR workflow2, and • How do data curation and archival science intersect? UK Data Archive workflow3 • How can comparing data curation and archival science lead to improvements in • Archival processing informed by concepts, such as appraisal, respect des fonds, local workflows and practices? original order, and archival value4, as well documented practices at peer institutions • Compare processing plans to discover areas of agreement and areas of conflict Data Transfer Data Processing Metadata Processing Preservation Access Unique Data Curation Processing Steps -Deposit agreement modeled on -Format transformation policies -Review and enhancement of -Varied retention periods, -Datasets treated as active and institutional repository license guided by reuse over preservation README file, used to accommodate determined by Board of Regents reusable -Funding model for sustainability -Create derivatives to promote diverse depositor needs Retention Schedule and funding -Datasets linked to publications access and re-use model -Bulk or individual file download -Correct erroneous or missing data Common Processing Steps -Data quarantine -Format identification -

A: Mandates and Standards for NPS Museum Collections

Appendix A: Mandates and Standards for NPS Museum Collections Page A. Overview...................................................................................................................................................... A:1 B. Laws, Regulations, and Conventions – NPS Cultural Collections......................................................... A:1 Laws related to NPS cultural collections ...................................................................................................... A:1 Regulations related to NPS cultural collections............................................................................................ A:4 International conventions related to NPS cultural collections....................................................................... A:5 Contacts for laws, regulations, and conventions – NPS cultural collections ................................................ A:6 C. Laws, Regulations, and Conventions – NPS Natural History Collections............................................. A:6 Laws related to NPS natural history collections ........................................................................................... A:6 Regulations related to NPS natural history collections................................................................................. A:8 International conventions related to NPS natural history collections............................................................ A:8 Contacts for laws, regulations, and conventions – NPS natural history collections .................................... -

Efficient Processing Guidelines

Guidelines for Efficient Archival Processing in the University of California Libraries Version 3.2 September 18, 2012 Developed by Next Generation Technical Services POT 3 Lightning Team 2 Kelley Bachli (UCLA) James Eason (UCB) Michelle Light (UCI) (Chair and POT 3 Liaison) Kelly McAnnaney (UCSD) Daryl Morrison (UCD) David Seubert (UCSB) With contributions from Lightning Team 2b Audra Eagle Yun (UCI) (Chair) Jillian Cuellar (UCLA) Teresa Mora (UCB) Adrian Turner (CDL) (POT 3 Liaison) Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.A. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.B. Goals .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.C. The Core, Recommended Principles .................................................................................................. 5 1.D. How to Use These Guidelines ............................................................................................................ 6 1.E. Why is MPLP Relevant to the UCs? .................................................................................................... 7 1.F. "Good-enough" Processing Can Be Quality Processing ..................................................................... 7 1.G. Implications Beyond -

Carolyn M. Chesarino. an Analysis of Finding Aid Structure and Authority Control for Large Architectural Collections

Carolyn M. Chesarino. An Analysis of Finding Aid Structure and Authority Control for Large Architectural Collections. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. November, 2012. 41 pages. Advisor: Stephanie W. Haas This study discusses best practices in describing architectural records in special collections repositories through encoded finding aids. It argues that metadata elements within these finding aids could serve as more effective access points if end users were more easily able to develop their own ways of highlighting relationships which exist within and across collections. Based on the information gathered from semi-structured interviews, this paper reports how other archivists developed institutional standards with which to catalog and process their architectural collections. Finally, this paper provides examples of what could be achieved in the realm of data visualization in an attempt to inspire repositories to make it easier for end users to extract the metadata that archivists and librarians spend so much time collecting. Headings: Architectural drawings Faceted classification Finding aids Libraries--Special collections AN ANALYSIS OF FINDING AID STRUCTURE AND AUTHORITY CONTROL FOR LARGE ARCHITECTURAL COLLECTIONS by Carolyn M. Chesarino A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina November 2012 Approved -

Archive Service Accreditation Guidance for Developing and Completing an Application June 2020

Archive Service Accreditation Guidance for developing and completing an application June 2020 0 Archive Service Accreditation – Guidance for developing and completing an application – June 2020 ARCHIVE SERVICE ACCREDITATION GUIDANCE Contents: Introduction to your Archive Service 3 A. Applicant details B. Service and Collection details Section 1 Organisational Health 8 1.1 Mission statement 1.2 Governance and management structures 1.3 Forward planning 1.4 Resources: spaces 1.5 Resources: finance 1.6 Resources: workforce Section 2 Collections 35 2.1 Collections management policies 2.2. Collections development 2.3 Collections information 2.4 Collections care and conservation Section 3 Stakeholders and their Experiences 70 3.1 Access policy 3.2 Access plans and planning 3.3. Access information, procedures and activities 1 Archive Service Accreditation – Guidance for developing and completing an application – June 2020 Introduction to this guidance Each requirement in the Archive Service Accreditation standard is accompanied by guidance, designed to help applicants to: Understand the significance of the requirement and the desired outcomes that come from its achievement Understand the expectations of the assessment process for that particular requirement, with some guidance on how to relate it to their particular archive type and scale Identify possible supporting evidence Find tools and resources that might assist with meeting the requirement This guidance is organised into: General guidance for the requirement as a whole Guidance for specific questions (indicated by their ‘Q’ number) where suitable Scaled guidance relevant to specific archive types and scales – where this scaled guidance is relevant to a specific question it is attached to the question. -

Efficient Processing Guidelines

Guidelines for Efficient Archival Processing in the University of California Libraries Version 3.2 September 18, 2012 Developed by Next Generation Technical Services POT 3 Lightning Team 2 Kelley Bachli (UCLA) James Eason (UCB) Michelle Light (UCI) (Chair and POT 3 Liaison) Kelly McAnnaney (UCSD) Daryl Morrison (UCD) David Seubert (UCSB) With contributions from Lightning Team 2b Audra Eagle Yun (UCI) (Chair) Jillian Cuellar (UCLA) Teresa Mora (UCB) Adrian Turner (CDL) (POT 3 Liaison) Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.A. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.B. Goals .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.C. The Core, Recommended Principles .................................................................................................. 5 1.D. How to Use These Guidelines ............................................................................................................ 6 1.E. Why is MPLP Relevant to the UCs? .................................................................................................... 7 1.F. "Good-enough" Processing Can Be Quality Processing ..................................................................... 7 1.G. Implications Beyond -

Preservation in the Digital Age a Review of Preservation Literature, 2009–10

56(1) LRTS 25 Preservation in the Digital Age A Review of Preservation Literature, 2009–10 Karen F. Gracy and Miriam B. Kahn This paper surveys research and professional literature on preservation-related topics published in 2009 and 2010, identifies key contributions to the field in peri- odicals, monographs, and research reports, and provides a guide to the changing landscape of preservation in the digital age. The authors have organized the reviewed literature into five major areas of interest: tensions in preservation work as libraries embrace digital resources, mass digitization and its effects on collec- tions, risk management and disaster response, digital preservation and curation, and education for preservation in the digital age. his review article critically examines the literature of preservation published T during a two-year period, 2009–10. Almost a decade has passed since the last review of the preservation literature appeared in Library Resources and Technical Services, covering the period of 1999–2001.1 In the interim, the evolu- tion of the preservation field noted by Croft has accelerated, encompassing whole areas of practice that were in their infancy at the turn of the twenty-first century. In her review, Croft identified ten areas of emphasis in the literature: clarifying preservation misconceptions triggered by the publication of Nicholson Baker’s Double Fold; the continued importance of the artifact in the wake of new digital reformatting technologies; remote storage; mass deacidification; physical treat- ment -

Digital Processing Framework

Digital Processing Framework Development of the Digital Processing Framework began after the second annual Born Digital Archiving eXchange unconference at Stanford University in 2016. There, a group of nine archivists saw a need for standardization, best practices, or general guidelines for processing digital archival materials. Members of this group were already engaged in digital processing and had knowledge and experience with acquiring, preserving, and managing born digital content but had a lot of questions about processing this type of material and making it accessible. They sought commonalities for processing digital materials and wanted to create a framework that would be extensible, flexible, useful, descriptive rather than prescriptive, and as simple as possible. CONTRIBUTORS Archivists whose time and experience contributed to this framework are as follows: Susanne Annand Sally DeBauche Erin Faulder Martin Gengenbach Karla Irwin Julie Musson Shira Peltzman Kate Tasker Laura Uglean Jackson Dorothy Waugh PURPOSE OF THE FRAMEWORK The aim of the framework is to suggest a minimum processing standard, to promote consistent practice among digital archivists, to establish common terminologies that can be used in further development of best practices, and to enhance research access. The framework brings archival and digital preservation best practices together to clarify the relationship between these related activities and thereby help practitioners make informed decisions about their collections. “Processing,” for the purpose of this framework, concerns activities that may overlap with other traditional archival functions including accessioning, preservation, and arrangement and description. Released: August 2018 1 This framework is intended to be useful and used. It should be adapted to meet the requirements of a particular organizational context. -

Computing the Total Cost of Archival Processing

TECHNICAL LEAFLET SEmS Computing the Total Cost of Archival Processing Thomas Wilsted Mid-Atlantic Rcgiond Mid-Atlantic Regional Archives Conference Reviewers Cynthia Pease Miller Karen Paul Constance Potter Editor's Note: The idea for a technical leaflet series originated with the New York Caucus of MARAC. The series, as developed by the Caucus, is intended to provide brief, practical information about selected archival topics suitable especially for beginners in the profession. The series editor welcomes proposals for future publications and comments from readers. Acknowledgements: The editor would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the reviewers, Bruce Ambacher and Martha Merselis toward the preparation of this leaflet for publication. Technical Leaflet Series Nancy Y. McGovern, Series Editor Donald Fisher Harrison Chair, MARAC Publications Committee Leon J. Stout Chair, MARAC Steering Committee 0 1989, Mid-Atlantic Regional Archives Conference All rights reserved Computing- the Total Cost of Archival Processing' by Thomas Wilsted With the concern in recent years over institutional accountability, archivists are increasingly interested in modern management techniques and in trying to measure the performance of their institutions. Certainly measurement is not new in the profession. Archivists for many years have counted the number of accessions, amount of archival material processed, number of reader inquiries and similar statistics. But while these statistics compare results from one month or one year to the next, they do not indicate the actual cost of each service in terms of time or money expended. If archivists are going to plan adequately for future development or justify their budgets, they must begin to quantify cost of time and materials. -

Archival Issues Journal of the Midwest Archives Conference Volume 37, Number 2, 2016

ISSN 10674993 Archival Issues Journal of the Midwest Archives Conference Volume 37, Number 2, 2016 CONTENTS Broken Promises: A Case Study in Reconciliation Elizabeth Joffrion and Lexie Tom ........................................................................... 7 Seen but Not Heard: A Case Study of K–12 Web Archiving and the Importance of Student Participation in the Archives JoyEllen Freeman ................................................................................................. 23 “Keep This, Toss That”: Improving Records Management at an Academic Institution Cliff Hight and James W. Smith ............................................................................ 43 Transcribing the Past: Crowdsourcing Transcription of Civil War Manuscripts Jacquelyn Slater Reese ........................................................................................... 59 PUBLICATION REVIEWS Interacting with History: Teaching with Primary Sources—edited by Katherine Lehman Past or Portal? Enhancing Undergraduate Learning through Special Collections and Archives—by Eleanor Mitchell, Peggy Seiden, and Suzy Taraba Reviewed by Tomaro Taylor, CA ....................................................................... 75 Appraisal and Acquisition: Innovative Practices for Archives and Special Collections—edited by Kate Theimer Reviewed by Sarah Dorpinghaus ....................................................................... 78 Archives in Libraries: What Librarians and Archivists Need to Know to Work Together—by Jeannette A. Bastian, Megan -

Harvard University Special Collections and Archives Joint Processing Guidelines

Harvard University Special Collections and Archives Joint Processing Guidelines Background and Executive Summary The Joint Processing Guidelines Working Group (JPGWG) was charged with “developing a suite of best practices and guidelines for archival and manuscript collections that will serve as a Harvard-wide framework in which local practices can be embedded.” We first conducted a survey of current processing practices at 18 Harvard repositories. Data showed that most repositories have two or fewer staff dedicated to archival processing, and that all repositories but one have a backlog of undescribed or under-described material. The JPGWG then produced a set of principles, frameworks, practices, and toolkits (hereafter referred to collectively as Guidelines) in which to guide future archival processing across Harvard Library. With a consistent and efficient approach across repositories, we hope to address inconsistencies in data for easier future migrations, create a user-friendly environment for users across repositories, provide a foundation for collecting statistics to make future fundraising and collaborative projects easier to scope and plan, and allow Harvard Library a deeper knowledge of the breadth and depth of its special collections materials. The Guidelines also touch on the importance of all repositories recognizing the importance of responsibly identifying and managing Harvard University records, acquired both through direct transfer from University offices and mixed in with faculty papers donations.1 In addition to these Processing Guidelines, archivists should also familiarize themselves with the General Records Schedule (GRS) to fully understand the scope and user access restriction periods applied to Harvard University records where they appear in both manuscript collections and record groups.