Archival Issues Journal of the Midwest Archives Conference Volume 37, Number 2, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INST 785 Section 0101 Documentation, Collection, and INST 785 Appraisal of Records Spring 2020

Course Syllabus – INST 785 Section 0101 Documentation, Collection, and INST 785 Appraisal of Records Spring 2020 Course Description Dr. Eric Hung he / him / his Appraisal is considered to be the archivist’s “first responsibility.” The [email protected] responsibility is “first” because appraisal comes first in the sequence of archival functions and thus influences all subsequent archival activities, and it is “first” in importance because appraisal determines what tiny sliver of Class Meetings: the total human documentary production will actually become “archives” Tuesdays, 6:00-8:45pm and thus a part of society’s history and collective memory. The archivist is HBK 0105 thereby actively shaping the future’s history of our own times. Office Hours The topic of appraisal remains one of considerable controversy in archives. ELMS Chat Office Hours: The archival literature includes debates over the definitions and indicators Mondays, 2:00-3:00pm, of long-term value, the purpose of appraisal, who intervenes in appraisal or by appointment. If you decisions, when in the information life cycle do they intervene, and which want to meet in-person, I methods work for which types of records and which types of organizations. am generally on campus The literature is replete with tensions between the theory and practice of on Tuesdays. appraisal and between questions of universalism versus specificity (by type of record, media, type of organization, time period, country, etc.). Syllabus Policy One of the problems with the literature on appraisal is that there are few This syllabus is a guide for methods for rigorously evaluating the feasibility or effectiveness of different the course and is subject appraisal methodologies. -

Archiving 2016 Preliminary Program

M ARCHIVING2016 A April 19-22, 2016 • Washington, DC R G www.imaging.org/archiving General Chair: Kari Smith, O MIT Libraries, Institute Archives and Special Collections R P Y R A N I M I L E R P Sponsored by the Society for Imaging Science and Technology April 19-22, 2016 • Washington, DC About the Conference The IS&T Archiving Conference brings together provides a forum to explore new strategies an international community of imaging experts and policies, and reports on successful projects and technicians as well as curators, managers, that can serve as benchmarks in the field. and researchers from libraries, archives, mu- Archiving 2016 is a blend of short courses, seums, records management repositories, in- invited focal papers, keynote talks, and formation technology institutions, and com- peer-reviewed oral and interactive display mercial enterprises to explore and discuss the presentations, offering attendees a unique field of digitization of cultural heritage and opportunity for gaining and exchanging archiving. The conference presents the latest knowledge and building networks among research results on digitization and curation, professionals. Cooperating Societies • American Institute for Conservation Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) • ALCTS Association for Library Collections & Technical Services • Coalition for Networked Information (CNI) • Digital Library Federation at CLIR . • Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) s e g o • IOP/Printing & Graphics Science Group V h p o t s • ISCC – Inter-Society Color Council i r h C • Museum Computer Network (MCN) : o t o h • The Royal Photographic Society P Short courses offer an intimate setting to gain more in-depth knowledge about technical aspects of digital archiving. -

10 Small Scale Academic Web Archiving: DACHS

10 Small Scale Academic Web Archiving: DACHS Hanno E. Lecher Leiden University [email protected] 10.1 Why Small Scale Academic Archiving? Considering the complexities of Web archiving and the demands on hard- and software as well as on expertise and personnel, one wonders whether such projects are only feasible for large scale institutions such as national libraries, or whether smaller institutions such as museums, university depart- ments and the like would also be able to perform the tasks required for a Web archive with long-term perspective. Even if the answer to this is yes, the question remains whether this is necessary at all. One could think that the Internet Archive in combination with the efforts of the increasing number of national libraries is already covering many, if not most relevant Web resources. Does academic or other small scale Web archiving make sense at all? Let me begin with this second question. The Internet Archive has done groundbreaking work as the first initiative attempting comprehensive archiv- ing of Web resources. Its success in accomplishing this has been revolution- ary, and it has laid the foundation on which many other projects have built their work. Still, examining what the Internet Archive and other holistic pro- jects1 can achieve it is easy to discover some limitations. Since their focus of collection is very broad, they have to rely on robots for a large part of their collecting activities, automatically grabbing as many Web pages as possible. This kind of capturing is often very superficial, missing parts located further down the tree, many pages being downloaded incompletely, and some file types as well as the hidden Web being ignored altogether. -

Selection in Web Archives: the Value of Archival Best Practices

WITTENBERG: SELECTION IN WEB ARCHIVES Selection in Web Archives: The Value of Archival Best Practices Jamie Wittenberg, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States of America Abstract: The abundance of valuable material available online has mobilized the development of preservation initiatives at collecting institutions that aim to capture and contextualize web content. Web archiving selection criteria are driven by the limitations inherent in harvesting technologies. Observing core archival principles like provenance and original order when establishing collection development policies for web content will help to ensure that archives continue to assure the authenticity of the materials they steward. Keywords: Web Archives; Archival Theory; Digital Libraries; Internet Content; Selection and Appraisal Introduction The abundance of valuable material available online has mobilized the development of preservation initiatives at collecting institutions that aim to capture and contextualize web content. Methodologies for web collection practices are institution and collection-specific. Among institutions charged with preserving cultural heritage, web archiving has become commonplace. However, the disparity between institutional selection and appraisal criteria reveals the absence of standardization for web archive establishment. The Australian web archive, for example, accessions content that it evaluates as having long-term research value. The Library of Congress web archive, represented by its Minerva team, established a collection -

Report of a Preservation Needs Assessment Executive Summary

Report of a Preservation Needs Assessment Wrentham Historical Commission Wrentham, MA March 29, 2018 Submitted on June 8, 2018 Sean Ferguson Preservation Specialist Northeast Document Conservation Center 100 Brickstone Square Andover, MA 01810 978.470.1010 [email protected] Executive Summary Paper-based, audiovisual and photographic materials housed in the Old Fiske Library Museum of the Wrentham Historical Commission (WHC) were assessed for preservation planning purposes by Sean Ferguson, Preservation Specialist for the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) in Wrentham, MA on March 29, 2018. Simmons College graduate student Lauren Hansen joined the assessment as an educational opportunity and observed and took part in the assessment. The assessment evaluated the buildings and environments as they relate to the preservation needs of the materials; examined current policies, storage, and handling procedures; and assessed the general condition of materials. Observations and recommendations are based on a pre-site visit questionnaire, a full-day site visit, and discussions with Chairman Greg Stahl, Vice Chairman Leo Baldyga, Treasurer and Secretary Susan Harris, Members Marion Cafferky, William Keyes, Alex Leonard, Kim Shipala, and Volunteer Cheri Leonard. Wrentham Historical Commission was established on March 27, 1967 and is responsible the stewardship and exhibition of Wrentham’s history. To these ends, WHC maintains an archives of historical materials and artifacts, manages the circa 1740’s Wampum House, and operates a plaque program to mark locations of historical significance in the Town. In 2010, WHC renovated the Old Fiske Museum, which was formally the town library, to make it suitable for the storage of historical collections. Following the renovation, the Commission relocated nearly all its historical collections into the Museum. -

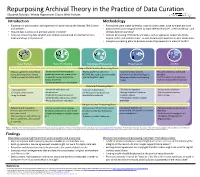

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation Elizabeth Rolando| Wendy Hagenmaier |Susan Wells Parham Introduction Methodology • Expansion of data curation and digital archiving services at the Georgia Tech Library • Process the same digital collection, once by data curator, once by digital archivist and Archives. • Data curation processing informed by OAIS Reference Model1, ICPSR workflow2, and • How do data curation and archival science intersect? UK Data Archive workflow3 • How can comparing data curation and archival science lead to improvements in • Archival processing informed by concepts, such as appraisal, respect des fonds, local workflows and practices? original order, and archival value4, as well documented practices at peer institutions • Compare processing plans to discover areas of agreement and areas of conflict Data Transfer Data Processing Metadata Processing Preservation Access Unique Data Curation Processing Steps -Deposit agreement modeled on -Format transformation policies -Review and enhancement of -Varied retention periods, -Datasets treated as active and institutional repository license guided by reuse over preservation README file, used to accommodate determined by Board of Regents reusable -Funding model for sustainability -Create derivatives to promote diverse depositor needs Retention Schedule and funding -Datasets linked to publications access and re-use model -Bulk or individual file download -Correct erroneous or missing data Common Processing Steps -Data quarantine -Format identification -

A: Mandates and Standards for NPS Museum Collections

Appendix A: Mandates and Standards for NPS Museum Collections Page A. Overview...................................................................................................................................................... A:1 B. Laws, Regulations, and Conventions – NPS Cultural Collections......................................................... A:1 Laws related to NPS cultural collections ...................................................................................................... A:1 Regulations related to NPS cultural collections............................................................................................ A:4 International conventions related to NPS cultural collections....................................................................... A:5 Contacts for laws, regulations, and conventions – NPS cultural collections ................................................ A:6 C. Laws, Regulations, and Conventions – NPS Natural History Collections............................................. A:6 Laws related to NPS natural history collections ........................................................................................... A:6 Regulations related to NPS natural history collections................................................................................. A:8 International conventions related to NPS natural history collections............................................................ A:8 Contacts for laws, regulations, and conventions – NPS natural history collections .................................... -

Yale University Library Preservation Department

Yale University Library Preservation Department 45th Annual Report July 2015-June 2016 Roberta Pilette January 17, 2016 Preservation Department Annual Rpt FY2016 1 Yale University Library Preservation Department 45th Annual Report July 2015-June 2016 Roberta Pilette, Director of Preservation and Chief Preservation Officer Murray Harrison, Senior Administrative Assistant Preservation Staffing: July 1, 2015 June 30, 2016 Positions budgeted: C&T 11.00 11.00 M&P 10.47 11.00 Positions filled: C&T 9.00 11.00 M&P 10.47 11.00 OVERVIEW OF THE DEPARTMENT The Yale University Library Preservation Department is responsible for the long-term preservation of all library materials. The Department consists of four units—Preservation Services; Digital Reformatting & Microfilm Services (DRMS); Conservation & Exhibition Services (CES) including Collections Conservation & Housing (CCH), Special Collections Conservation (SCC) and Exhibit Production Support (EPS); and Digital Preservation Services. The Department organizational chart can be found in Appendix I, the annual statistics for the Department can be found in Appendix II. 344 Winchester moving & more construction The construction of that portion of the department associated with the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript (BRBL) Technical Services construction was completed during the first quarter of FY16. The move for Preservation Administration, Preservation Services, and Digital Preservation Services took place in August 2015. Those moves went smoothly and the units settled into the new spaces. Digital Preservation Services moved all of their equipment into their new spaces and spent the year making significant use of the enlarged work areas. Digital Preservation and the Born Digital Working group collaborated on the specifications for the new di Bonaventura Digital Archeology and Preservation laboratory. -

2016 Program

Culture Builds Communities Preserving the Past, Shaping the Future International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums October 9–12, 2016 ▪ Phoenix, Arizona Presented by the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services SCHOOL FOR ADVANCED RESEARCH ANNE RAY INTERNSHIPS Interested in working with Native American collections? The Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, NM, offers two nine-month paid internships to college graduates or junior museum professionals. Internships include a salary, housing, and book and travel allowances. Interns participate in the daily collections and programming activities and also benefit from the mentorship of the Anne Ray scholar. Deadline to apply March 1 internships.sarweb.org ANNE RAY FELLOWSHIP FOR SCHOLARS Are you a Native American scholar with a master’s or PhD in the arts, humanities, or social sciences who has an interest in mentorship? Apply for a nine-month Anne Ray Fellowship at SAR. The Anne Ray scholar works independently on their own writing or curatorial research projects, while also providing mentorship to the Anne Ray interns working at the IARC. The fellow receives a stipend, housing, and office space. Deadline to apply November 1 annerayscholar.sarweb.org For more information about SAR, please visit www.sarweb.org INNOVATIVE SOCIAL SCIENCE AND NATIVE AMERICAN ART Welcome to the International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums Wild Horse Pass Resort & Spa, Phoenix, AZ October 9-12, 2016 About the Program Cover Table of Contents Harry Fonseca was among a critical generation of twentieth- Special Thanks, Page 2 century Native artists who, inspired by tradition, created work that transcended expectations. -

Efficient Processing Guidelines

Guidelines for Efficient Archival Processing in the University of California Libraries Version 3.2 September 18, 2012 Developed by Next Generation Technical Services POT 3 Lightning Team 2 Kelley Bachli (UCLA) James Eason (UCB) Michelle Light (UCI) (Chair and POT 3 Liaison) Kelly McAnnaney (UCSD) Daryl Morrison (UCD) David Seubert (UCSB) With contributions from Lightning Team 2b Audra Eagle Yun (UCI) (Chair) Jillian Cuellar (UCLA) Teresa Mora (UCB) Adrian Turner (CDL) (POT 3 Liaison) Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.A. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.B. Goals .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.C. The Core, Recommended Principles .................................................................................................. 5 1.D. How to Use These Guidelines ............................................................................................................ 6 1.E. Why is MPLP Relevant to the UCs? .................................................................................................... 7 1.F. "Good-enough" Processing Can Be Quality Processing ..................................................................... 7 1.G. Implications Beyond -

Carolyn M. Chesarino. an Analysis of Finding Aid Structure and Authority Control for Large Architectural Collections

Carolyn M. Chesarino. An Analysis of Finding Aid Structure and Authority Control for Large Architectural Collections. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. November, 2012. 41 pages. Advisor: Stephanie W. Haas This study discusses best practices in describing architectural records in special collections repositories through encoded finding aids. It argues that metadata elements within these finding aids could serve as more effective access points if end users were more easily able to develop their own ways of highlighting relationships which exist within and across collections. Based on the information gathered from semi-structured interviews, this paper reports how other archivists developed institutional standards with which to catalog and process their architectural collections. Finally, this paper provides examples of what could be achieved in the realm of data visualization in an attempt to inspire repositories to make it easier for end users to extract the metadata that archivists and librarians spend so much time collecting. Headings: Architectural drawings Faceted classification Finding aids Libraries--Special collections AN ANALYSIS OF FINDING AID STRUCTURE AND AUTHORITY CONTROL FOR LARGE ARCHITECTURAL COLLECTIONS by Carolyn M. Chesarino A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina November 2012 Approved -

Archive Service Accreditation Guidance for Developing and Completing an Application June 2020

Archive Service Accreditation Guidance for developing and completing an application June 2020 0 Archive Service Accreditation – Guidance for developing and completing an application – June 2020 ARCHIVE SERVICE ACCREDITATION GUIDANCE Contents: Introduction to your Archive Service 3 A. Applicant details B. Service and Collection details Section 1 Organisational Health 8 1.1 Mission statement 1.2 Governance and management structures 1.3 Forward planning 1.4 Resources: spaces 1.5 Resources: finance 1.6 Resources: workforce Section 2 Collections 35 2.1 Collections management policies 2.2. Collections development 2.3 Collections information 2.4 Collections care and conservation Section 3 Stakeholders and their Experiences 70 3.1 Access policy 3.2 Access plans and planning 3.3. Access information, procedures and activities 1 Archive Service Accreditation – Guidance for developing and completing an application – June 2020 Introduction to this guidance Each requirement in the Archive Service Accreditation standard is accompanied by guidance, designed to help applicants to: Understand the significance of the requirement and the desired outcomes that come from its achievement Understand the expectations of the assessment process for that particular requirement, with some guidance on how to relate it to their particular archive type and scale Identify possible supporting evidence Find tools and resources that might assist with meeting the requirement This guidance is organised into: General guidance for the requirement as a whole Guidance for specific questions (indicated by their ‘Q’ number) where suitable Scaled guidance relevant to specific archive types and scales – where this scaled guidance is relevant to a specific question it is attached to the question.