Preservation in the Digital Age a Review of Preservation Literature, 2009–10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamie Shiers, CERN

Investing in Curation A Shared Path to Sustainability [email protected] Data Preservation in HEP (DPHEP) Outline 1. Pick 2 of the messages from the roadmap & comment – I could comment on all – but not in 10’ 1. What (+ve) impact has 4C already had on us? – Avoiding overlap with the above 1. A point for discussion – shared responsiblity / action THE MESSAGES The 4C Roadmap Messages 1. Identify the value of digital assets and make choices 2. Demand and choose more efficient systems 3. Develop scalable services and infrastructure 4. Design digital curation as a sustainable service 5. Make funding dependent on costing digital assets across the whole lifecycle 6. Be collaborative and transparent to drive down costs IMPACT OF 4C ON DPHEP International Collaboration for Data Preservation and Long Term Analysis in High Energy Physics “LHC Cost Model” (simplified) Start with 10PB, then +50PB/year, then +50% every 3y (or +15% / year) 10EB 1EB 6 Case B) increasing archive growth Total cost: ~$59.9M (~$2M / year) 7 1. Identify the value of digital assets and make choices • Today, significant volumes of HEP data are thrown away “at birth” – i.e. via very strict filters (aka triggers) B4 writing to storage To 1st approximation ALL remaining data needs to be kept for a few decades • “Value” can be measured in a number of ways: – Scientific publications / results; – Educational / cultural impact; – “Spin-offs” – e.g. superconductivity, ICT, vacuum technology. Why build an LHC? BEFORE! 1 – Long Tail of Papers 2 – New Theore cal Insights 3 4 3 – “Discovery” to “Precision” Volume: 100PB + ~50PB/year (+400PB/year from 2020) 11 Zimmermann( Alain Blondel TLEP design study r-ECFA 2013-07-20 5 Balance sheet – Tevatron@FNAL • 20 year investment in Tevatron ~ $4B • Students $4B • Magnets and MRI $5-10B } ~ $50B total • Computing $40B Very rough calculation – but confirms our gut feeling that investment in fundamental science pays off I think there is an opportunity for someone to repeat this exercise more rigorously cf. -

The Preservation Evolution a Review of Preservation Literature, 1999–2001

47(2) LRTS 59 The Preservation Evolution A Review of Preservation Literature, 1999–2001 JeanAnn Croft The literature representing 1999 to 2001 reveals that the preservation field is absorbed in an evolution. The literature demonstrates that trusted practices are changing to improve outcomes and further advance the preservation field. Simultaneously, in the wake of the digital revolution, preservation professionals dream about merging traditional and digital technologies in the hope that both long-term preservation and enhanced access will be achieved. This article attempts to relate the values of the discipline in order to inspire further research and persuade more work in formulating hypotheses to integrate preservation the- ory and practice. Finally, this overview of the literature will communicate the scope of the preservation problem, clarify misconceptions in the field, and docu- ment areas that warrant further investigation and refinement. he literature representing 1999 to 2001 reveals that the preservation field is Tcontinually absorbed in an evolution. This literature review examines the trends and customs of the preservation field as documented in the literature, and attempts to relate the values of the discipline in order to inspire further research and persuade more work in formulating hypotheses to integrate preservation theory and practice. Finally, this depiction of the literature will communicate the scope of the preservation problem, clarify misconceptions in the field, and document areas that warrant further investigation and refinement. Following up the preceding preservation literature reviews that have been pub- lished in this journal, this work provides a sampling of the preservation litera- ture and will not include book reviews, annual reports, preservation project announcements, technical leaflets, and strictly specialized conservation litera- ture. -

Module 8 Wiki Guide

Best Practices for Biomedical Research Data Management Harvard Medical School, The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine Module 8 Wiki Guide Learning Objectives and Outcomes: 1. Emphasize characteristics of long-term data curation and preservation that build on and extend active data management ● It is the purview of permanent archiving and preservation to take over stewardship and ensure that the data do not become technologically obsolete and no longer permanently accessible. ○ The selection of a repository to ensure that certain technical processes are performed routinely and reliably to maintain data integrity ○ Determining the costs and steps necessary to address preservation issues such as technological obsolescence inhibiting data access ○ Consistent, citable access to data and associated contextual records ○ Ensuring that protected data stays protected through repository-governed access control ● Data Management ○ Refers to the handling, manipulation, and retention of data generated within the context of the scientific process ○ Use of this term has become more common as funding agencies require researchers to develop and implement structured plans as part of grant-funded project activities ● Digital Stewardship ○ Contributions to the longevity and usefulness of digital content by its caretakers that may occur within, but often outside of, a formal digital preservation program ○ Encompasses all activities related to the care and management of digital objects over time, and addresses all phases of the digital object lifecycle 2. Distinguish between preservation and curation ● Digital Curation ○ The combination of data curation and digital preservation ○ There tends to be a relatively strong orientation toward authenticity, trustworthiness, and long-term preservation ○ Maintaining and adding value to a trusted body of digital information for future and current use. -

View Presentation

a centre of expertise in data curation and preservation The Digital Curation Centre Hugh Corley DCC Services and Outreach Liaison Officer Funders: 1 University College London Information Day :: 16th January 2007 a centre of expertise in data curation and preservation What is an Information Day • Learn • Discuss • Action Funders: 2 University College London Information Day :: 16th January 2007 a centre of expertise in data curation and preservation Overview • Digital Curation • Aims of the DCC • Work of the DCC Funders: 3 University College London Information Day :: 16th January 2007 a centre of expertise in data curation and preservation Digital Curation • Active management of data over life- cycle of scholarly and scientific interest – reproducibility – reuse • Appreciation of differences between disciplines • Ubiquitous relationship with digital information Funders: 4 University College London Information Day :: 16th January 2007 a centre of expertise in data curation and preservation UK Digital Curation Centre • CCLRC • University of Edinburgh • HATII • UKOLN Funders: 5 University College London Information Day :: 16th January 2007 a centre of expertise in data curation and preservation UK Digital Curation Centre Support and promote continuing improvement in the quality of data curation and digital preservation activity Drivers – increasing awareness that digital assets are reusable – continuing access vital to ensure contemporary scholarship is reproducible and verifiable – digital assets are fragile Funders: 6 University College -

Front Page Title of Paper in Full: Centered

Preservation Is Not a Place 1 4th International Digital Curation Conference December 2008 Preservation Is Not a Place Stephen Abrams, Patricia Cruse, John Kunze California Digital Library, University of California December 2008 Abstract The Digital Preservation Program of the California Digital Library (CDL) is engaged in a process of reinvention involving significant transformations of its outlook, effort, and infrastructure. This includes a re-articulation of its mission in terms of digital curation, rather than preservation; encouraging a programmatic, rather than a project-oriented approach to curation activities; and a renewed emphasis on services, rather than systems. This last shift was motivated by a desire to deprecate the centrality of the repository as place. Having the repository as the locus for curation activity has resulted in the deployment of a somewhat cumbersome monolithic system that falls short of desired goals for responsiveness to rapidly changing user needs and operational and administrative sustainability. The Program is pursuing a path towards a new curation environment based on the principle of devolving curation function to a set of small, simple, loosely-coupled services. In considering this new infrastructure the Program is relying upon a highly deliberative process starting from first principles drawn from library and archival science. This is followed by a stagewise progressesion of identifying core preservable values, devising strategies promoting those values, defining abstract services embodying those strategies, and, finally, developing systems that instantiate those services. This paper presents a snapshot of the Program’s transformative efforts in its early phase. The 4th International Digital Curation Conference taking place in Edinburgh, Scotland over 1-3 December 2008 will address the theme Radical Sharing: Transforming Science?. -

Report of a Preservation Needs Assessment Executive Summary

Report of a Preservation Needs Assessment Wrentham Historical Commission Wrentham, MA March 29, 2018 Submitted on June 8, 2018 Sean Ferguson Preservation Specialist Northeast Document Conservation Center 100 Brickstone Square Andover, MA 01810 978.470.1010 [email protected] Executive Summary Paper-based, audiovisual and photographic materials housed in the Old Fiske Library Museum of the Wrentham Historical Commission (WHC) were assessed for preservation planning purposes by Sean Ferguson, Preservation Specialist for the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) in Wrentham, MA on March 29, 2018. Simmons College graduate student Lauren Hansen joined the assessment as an educational opportunity and observed and took part in the assessment. The assessment evaluated the buildings and environments as they relate to the preservation needs of the materials; examined current policies, storage, and handling procedures; and assessed the general condition of materials. Observations and recommendations are based on a pre-site visit questionnaire, a full-day site visit, and discussions with Chairman Greg Stahl, Vice Chairman Leo Baldyga, Treasurer and Secretary Susan Harris, Members Marion Cafferky, William Keyes, Alex Leonard, Kim Shipala, and Volunteer Cheri Leonard. Wrentham Historical Commission was established on March 27, 1967 and is responsible the stewardship and exhibition of Wrentham’s history. To these ends, WHC maintains an archives of historical materials and artifacts, manages the circa 1740’s Wampum House, and operates a plaque program to mark locations of historical significance in the Town. In 2010, WHC renovated the Old Fiske Museum, which was formally the town library, to make it suitable for the storage of historical collections. Following the renovation, the Commission relocated nearly all its historical collections into the Museum. -

Analog, the Sequel: an Analysis of Current Film Archiving Practice and Hesitance to Embrace Digital Preservation by Suzanna Conrad

ANALOG, THE SEQUEL: AN ANALYSIS OF CURRENT FILM ARCHIVING PRACTICE AND HESITANCE TO EMBRACE DIGITAL PRESERVATION BY SUZANNA CONRAD ABSTRACT: Film archives preserve materials of significant cultural heritage. While current practice helps ensure 35mm film will last for at least one hundred years, digi- tal technology is creating new challenges for the traditional means of preservation. Digitally produced films can be preserved via film stock; however, digital ancillary materials and assets in many cases cannot be preserved using traditional analog means. Strategy and action for preserving this content needs to be addressed before further content is lost. To understand the current perspective of the film archives, especially in regards to the film industry’s marked hesitation to embrace digital preservation, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ paper “The Digital Dilemma: Strategic Issues in Archiving and Accessing Digital Motion Picture Materials” was closely evaluated. To supplement this analysis, an interview was conducted with the collections curator at the Academy Film Archive, who explained the archives’ current approach to curation and its hesitation to move to digital technologies for preservation. Introduction Moving images are a vital part of our cultural heritage. The music, film, and broadcasting industries, as well as academic and cultural institutions, have amassed a “legacy of primary source materials” of immense value. These sources make the last one hundred years understandable as an era of the “media of the modernity.”1 Motion pictures and films were established as vital archival records as early as the 1930s with the National Archives Act, which included motion pictures in the definition of “objects of archival interest.”2 As cultural artifacts, moving images deserve archival care and preservation.3 However, the art of preserving moving images and film can at times be daunting. -

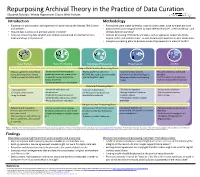

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation Elizabeth Rolando| Wendy Hagenmaier |Susan Wells Parham Introduction Methodology • Expansion of data curation and digital archiving services at the Georgia Tech Library • Process the same digital collection, once by data curator, once by digital archivist and Archives. • Data curation processing informed by OAIS Reference Model1, ICPSR workflow2, and • How do data curation and archival science intersect? UK Data Archive workflow3 • How can comparing data curation and archival science lead to improvements in • Archival processing informed by concepts, such as appraisal, respect des fonds, local workflows and practices? original order, and archival value4, as well documented practices at peer institutions • Compare processing plans to discover areas of agreement and areas of conflict Data Transfer Data Processing Metadata Processing Preservation Access Unique Data Curation Processing Steps -Deposit agreement modeled on -Format transformation policies -Review and enhancement of -Varied retention periods, -Datasets treated as active and institutional repository license guided by reuse over preservation README file, used to accommodate determined by Board of Regents reusable -Funding model for sustainability -Create derivatives to promote diverse depositor needs Retention Schedule and funding -Datasets linked to publications access and re-use model -Bulk or individual file download -Correct erroneous or missing data Common Processing Steps -Data quarantine -Format identification -

A: Mandates and Standards for NPS Museum Collections

Appendix A: Mandates and Standards for NPS Museum Collections Page A. Overview...................................................................................................................................................... A:1 B. Laws, Regulations, and Conventions – NPS Cultural Collections......................................................... A:1 Laws related to NPS cultural collections ...................................................................................................... A:1 Regulations related to NPS cultural collections............................................................................................ A:4 International conventions related to NPS cultural collections....................................................................... A:5 Contacts for laws, regulations, and conventions – NPS cultural collections ................................................ A:6 C. Laws, Regulations, and Conventions – NPS Natural History Collections............................................. A:6 Laws related to NPS natural history collections ........................................................................................... A:6 Regulations related to NPS natural history collections................................................................................. A:8 International conventions related to NPS natural history collections............................................................ A:8 Contacts for laws, regulations, and conventions – NPS natural history collections .................................... -

Mass Deacidification of Library and Archive Materials

Columbia University Libraries Mass Deacidification of Library and Archive Materials Final Report to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation September 2009 Principal Investigator: James G. Neal Vice President for Information Services and University Librarian Columbia University 535 West 114th Street New York, New York 10027 212.854.2247 Grant Period: May 1, 2008-July 31, 2009 Reporting Period: May 1, 2008-July 31, 2009 Mass Deacidification of Library and Archive Materials Final Report to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Columbia University Libraries received an award of $27,500 in April 2008 from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to support a survey and report of the need for the deacidification of newly acquired print volumes in major research libraries. The study group included members from CUR, NYU, Yale, and the Mellon Foundation. In March 2009, the Mellon Foundation approved a no-cost extension through July 31, 2009 to host the originally scheduled March planning meeting in April and to allow additional time for the university's account department to process and pay all expenses charged to the grant. The result is the attached report, Mass Deacidifcation: The Needfor a National Program. The principal investigator, Jim Neal, and Columbia's Offce of the Controller worked together to complete the Financial Report, which was signed and submitted directly from the Office of the Controller. As indicated in the Financial Report, this grant was underspent by $6,647 (including interest income of $198), primarily due to significant savings in travel costs. A check in the amount of $6,647 wil be refunded to the Mellon Foundation. -

The Preservation of Archaeological Records and Photographs

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations Anthropology, Department of 12-2010 The Preservation of Archaeological Records and Photographs Kelli Bacon University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses Part of the Anthropology Commons Bacon, Kelli, "The Preservation of Archaeological Records and Photographs" (2010). Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations. 9. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE PRESERVATION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS By Kelli Bacon A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Anthropology Under the Supervision of Professor LuAnn Wandsnider Lincoln, Nebraska December 2010 THE PRESERVATION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Kelli Bacon, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2010 Advisor: LuAnn Wandsnider Substantive and organized research about archaeological records and photograph preservation, especially those written by and for archaeologists, are few. Although the Society for American Archaeology has a code of ethics regarding archaeological records preservation, and the federal government has regulations regarding the care and preservation of federally owned archaeological collections, there is a lack of resources. This is detrimental to archaeology because not all archaeologists, given the maturity of the discipline, understand how important it is to preserve archaeological records and photographs. -

Efficient Processing Guidelines

Guidelines for Efficient Archival Processing in the University of California Libraries Version 3.2 September 18, 2012 Developed by Next Generation Technical Services POT 3 Lightning Team 2 Kelley Bachli (UCLA) James Eason (UCB) Michelle Light (UCI) (Chair and POT 3 Liaison) Kelly McAnnaney (UCSD) Daryl Morrison (UCD) David Seubert (UCSB) With contributions from Lightning Team 2b Audra Eagle Yun (UCI) (Chair) Jillian Cuellar (UCLA) Teresa Mora (UCB) Adrian Turner (CDL) (POT 3 Liaison) Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.A. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.B. Goals .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.C. The Core, Recommended Principles .................................................................................................. 5 1.D. How to Use These Guidelines ............................................................................................................ 6 1.E. Why is MPLP Relevant to the UCs? .................................................................................................... 7 1.F. "Good-enough" Processing Can Be Quality Processing ..................................................................... 7 1.G. Implications Beyond