Basics of DC Drives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design and Optimization of an Electromagnetic Railgun

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports 2018 DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION OF AN ELECTROMAGNETIC RAILGUN Nihar S. Brahmbhatt Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Copyright 2018 Nihar S. Brahmbhatt Recommended Citation Brahmbhatt, Nihar S., "DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION OF AN ELECTROMAGNETIC RAILGUN", Open Access Master's Report, Michigan Technological University, 2018. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/651 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etdr Part of the Controls and Control Theory Commons DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION OF AN ELECTROMAGNETIC RAIL GUN By Nihar S. Brahmbhatt A REPORT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In Electrical Engineering MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Nihar S. Brahmbhatt This report has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Electrical Engineering. Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Report Advisor: Dr. Wayne W. Weaver Committee Member: Dr. John Pakkala Committee Member: Dr. Sumit Paudyal Department Chair: Dr. Daniel R. Fuhrmann Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments........................................................................................................... 8 List of Figures ................................................................................................................ -

Electric Motors

SPECIFICATION GUIDE ELECTRIC MOTORS Motors | Automation | Energy | Transmission & Distribution | Coatings www.weg.net Specification of Electric Motors WEG, which began in 1961 as a small factory of electric motors, has become a leading global supplier of electronic products for different segments. The search for excellence has resulted in the diversification of the business, adding to the electric motors products which provide from power generation to more efficient means of use. This diversification has been a solid foundation for the growth of the company which, for offering more complete solutions, currently serves its customers in a dedicated manner. Even after more than 50 years of history and continued growth, electric motors remain one of WEG’s main products. Aligned with the market, WEG develops its portfolio of products always thinking about the special features of each application. In order to provide the basis for the success of WEG Motors, this simple and objective guide was created to help those who buy, sell and work with such equipment. It brings important information for the operation of various types of motors. Enjoy your reading. Specification of Electric Motors 3 www.weg.net Table of Contents 1. Fundamental Concepts ......................................6 4. Acceleration Characteristics ..........................25 1.1 Electric Motors ...................................................6 4.1 Torque ..............................................................25 1.2 Basic Concepts ..................................................7 -

2016-09-27-2-Generator-Basics

Generator Basics Basic Power Generation • Generator Arrangement • Main Components • Circuit – Generator with a PMG – Generator without a PMG – Brush type –AREP •PMG Rotor • Exciter Stator • Exciter Rotor • Main Rotor • Main Stator • Laminations • VPI Generator Arrangement • Most modern, larger generators have a stationary armature (stator) with a rotating current-carrying conductor (rotor or revolving field). Armature coils Revolving field coils Main Electrical Components: Cutaway Main Electrical Components: Diagram Circuit: Generator with a PMG • As the PMG rotor rotates, it produces AC voltage in the PMG stator. • The regulator rectifies this voltage and applies DC to the exciter stator. • A three-phase AC voltage appears at the exciter rotor and is in turn rectified by the rotating rectifiers. • The DC voltage appears in the main revolving field and induces a higher AC voltage in the main stator. • This voltage is sensed by the regulator, compared to a reference level, and output voltage is adjusted accordingly. Circuit: Generator without a PMG • As the revolving field rotates, residual magnetism in it produces a small ac voltage in the main stator. • The regulator rectifies this voltage and applies dc to the exciter stator. • A three-phase AC voltage appears at the exciter rotor and is in turn rectified by the rotating rectifiers. • The magnetic field from the rotor induces a higher voltage in the main stator. • This voltage is sensed by the regulator, compared to a reference level, and output voltage is adjusted accordingly. Circuit: Brush Type (Static) • DC voltage is fed External Stator (armature) directly to the main Source revolving field through slip rings. -

DC Motor Workshop

DC Motor Annotated Handout American Physical Society A. What You Already Know Make a labeled drawing to show what you think is inside the motor. Write down how you think the motor works. Please do this independently. This important step forces students to create a preliminary mental model for the motor, which will be their starting point. Since they are writing it down, they can compare it with their answer to the same question at the end of the activity. B. Observing and Disassembling the Motor 1. Use the small screwdriver to take the motor apart by bending back the two metal tabs that hold the white plastic end-piece in place. Pull off this plastic end-piece, and then slide out the part that spins, which is called the armature. 2. Describe what you see. 3. How do you think the motor works? Discuss this question with the others in your group. C. Mounting the Armature 1. Use the diagram below to locate the commutator—the split ring around the motor shaft. This is the armature. Shaft Commutator Coil of wire (electromagnetic) 2. Look at the drawing on the next page and find the brushes—two short ends of bare wire that make a "V". The brushes will make electrical contact with the commutator, and gravity will hold them together. In addition the brushes will support one end of the armature and cradle it to prevent side- to-side movement. 1 3. Using the cup, the two rubber bands, the piece of bare wire, and the three pieces of insulated wire, mount the armature as in the diagram below. -

Model Characteristics and Properties of Nanorobots in the Bloodstream Michael Makoto Zimmer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Model Characteristics and Properties of Nanorobots in the Bloodstream Michael Makoto Zimmer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY FAMU-FSU COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING MODEL CHARACTERISTICS AND PROPERTIES OF NANOROBOTS IN THE BLOODSTREAM By MICHAEL MAKOTO ZIMMER A Thesis submitted to the Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Michael M. Zimmer defended on April 4, 2005. ___________________________ Yaw A. Owusu Professor Directing Thesis ___________________________ Rodney G. Roberts Outside Committee Member ___________________________ Reginald Parker Committee Member ___________________________ Chun Zhang Committee Member Approved: _______________________ Hsu-Pin (Ben) Wang, Chairperson Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering _______________________ Chin-Jen Chen, Dean FAMU-FSU College of Engineering The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For the advancement of technology where engineers make the future possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to give thanks and appreciation to Dr. Yaw A. Owusu who first gave me the chance and motivation to pursue my master’s degree. I also want to give my thanks to my undergraduate team who helped in obtaining information for my thesis and helped in setting up my experiments. Many thanks go to Dr. Hans Chapman for his technical assistance. I want to acknowledge the whole Undergraduate Research Center for Cutting Edge Technology (URCCET) for their support and continuous input in my studies. -

ALTERNATORS ➣ Armature Windings ➣ Wye and Delta Connections ➣ Distribution Or Breadth Factor Or Winding Factor Or Spread Factor ➣ Equation of Induced E.M.F

CHAPTER37 Learning Objectives ➣ Basic Principle ➣ Stationary Armature ➣ Rotor ALTERNATORS ➣ Armature Windings ➣ Wye and Delta Connections ➣ Distribution or Breadth Factor or Winding Factor or Spread Factor ➣ Equation of Induced E.M.F. ➣ Factors Affecting Alternator Size ➣ Alternator on Load ➣ Synchronous Reactance ➣ Vector Diagrams of Loaded Alternator ➣ Voltage Regulation ➣ Rothert's M.M.F. or Ampere-turn Method ➣ Zero Power Factor Method or Potier Method ➣ Operation of Salient Pole Synchronous Machine ➣ Power Developed by a Synchonous Generator ➣ Parallel Operation of Alternators ➣ Synchronizing of Alternators ➣ Alternators Connected to Infinite Bus-bars ➣ Synchronizing Torque Tsy ➣ Alternative Expression for Ç Alternator Synchronizing Power ➣ Effect of Unequal Voltages ➣ Distribution of Load ➣ Maximum Power Output ➣ Questions and Answers on Alternators 1402 Electrical Technology 37.1. Basic Principle A.C. generators or alternators (as they are DC generator usually called) operate on the same fundamental principles of electromagnetic induction as d.c. generators. They also consist of an armature winding and a magnetic field. But there is one important difference between the two. Whereas in d.c. generators, the armature rotates and the field system is stationary, the arrangement Single split ring commutator in alternators is just the reverse of it. In their case, standard construction consists of armature winding mounted on a stationary element called stator and field windings on a rotating element called rotor. The details of construction are shown in Fig. 37.1. Fig. 37.1 The stator consists of a cast-iron frame, which supports the armature core, having slots on its inner periphery for housing the armature conductors. The rotor is like a flywheel having alternate N and S poles fixed to its outer rim. -

ELECTRICAL SCIENCE Module 10 AC Generators

DOE Fundamentals ELECTRICAL SCIENCE Module 10 AC Generators Electrical Science AC Generators TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Co nte nts TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................... i LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................ii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ iii REFERENCES ................................................................................................................iv OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. v AC GENERATOR COMPONENTS ................................................................................. 1 Field ............................................................................................................................. 1 Armature ...................................................................................................................... 1 Prime Mover ................................................................................................................ 1 Rotor ............................................................................................................................ 1 Stator ........................................................................................................................... 2 Slip Rings ................................................................................................................... -

ON Semiconductor Is

ON Semiconductor Is Now To learn more about onsemi™, please visit our website at www.onsemi.com onsemi and and other names, marks, and brands are registered and/or common law trademarks of Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC dba “onsemi” or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. onsemi owns the rights to a number of patents, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, and other intellectual property. A listing of onsemi product/patent coverage may be accessed at www.onsemi.com/site/pdf/Patent-Marking.pdf. onsemi reserves the right to make changes at any time to any products or information herein, without notice. The information herein is provided “as-is” and onsemi makes no warranty, representation or guarantee regarding the accuracy of the information, product features, availability, functionality, or suitability of its products for any particular purpose, nor does onsemi assume any liability arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit, and specifically disclaims any and all liability, including without limitation special, consequential or incidental damages. Buyer is responsible for its products and applications using onsemi products, including compliance with all laws, regulations and safety requirements or standards, regardless of any support or applications information provided by onsemi. “Typical” parameters which may be provided in onsemi data sheets and/ or specifications can and do vary in different applications and actual performance may vary over time. All operating parameters, including “Typicals” must be validated for each customer application by customer’s technical experts. onsemi does not convey any license under any of its intellectual property rights nor the rights of others. -

Electrical and Magnetic Model Coupling of Permanent Magnet Machines Based on the Harmonic Analysis

EG-05 1 Electrical and Magnetic Model Coupling of Permanent Magnet Machines Based on the Harmonic Analysis M. Merdzan, S. Jumayev, A. Borisavljevic, K. O. Boynov, J. J. H. Paulides, and E. A. Lomonova Department of Electrical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven 5612 AZ, The Netherlands A widely used method for the magnetic field calculation in permanent magnet (PM) machines is the harmonic modeling (HM) method. Despite its many advantages, the application of this method is limited to machines in which armature currents, as a source of the magnetic field, are known. Since most of PM machines are supplied with three phase voltages, any variation of parameters in the armature electric circuit could lead to the uncertainty in knowing the armature currents and therefore limit use of the harmonic modeling method. In this paper an approach for overcoming this limitation is presented which enables the calculation of the magnetic field in PM machines without a priori knowledge of the armature currents. Index Terms—Harmonic modeling, permanent magnet machines, high-speed machines, rotor eddy currents. I. INTRODUCTION machines is presented. The method is based on a coupling of ARMONIC modeling (HM) technique is a fast and the harmonic model solution with the equation describing the H precise tool for the magnetic field analysis in electrical armature electric circuit. machines [1]. Different types and configurations of machines can be analyzed using this approach, among them rotating permanent magnet (PM) machines [2]-[3]. II. HARMONIC MODELING OF PERMANENT MAGNET Harmonic analysis is based on Fourier representation of MACHINES sources of the magnetic field which have to be expressed in terms of magnetization and current density [1]. -

DC Motor, How It Works?

DC Motor, how it works? You can find DC motors in many portable home appliances, automobiles and types of industrial equipment. In this video we will logically understand the operation and construction of a commercial DC motor. The Working Let’s first start with the simplest DC motor possible. It looks like as shown in the Fig.1. The stator is a permanent magnet and provides a constant magnetic field. The armature, which is the rotating part, is a simple coil. Fig.1 A simplified D.C motor, which runs with permanent magnet The armature is connected to a DC power source through a pair of commutator rings. When the current flows through the coil an electromagnetic force is induced on it according to the Lorentz law, so the coil will start to rotate. The force induced due to the electromagnetic induction is shown using 'red arrows' in the Fig.2. Fig.2 The electromagnetic force induced on the coils make the armature coil rotate You will notice that as the coil rotates, the commutator rings connect with the power source of opposite polarity. As a result, on the left side of the coil the electricity will always flow ‘away ‘and on the right side , electricity will always flow ‘towards ‘. This ensures that the torque action is also in the same direction throughout the motion, so the coil will continue rotating. Fig.3 The commutator rings make sure a uni-directional current flows through the left and right part of the coil Improving the Torque action But if you observe the torque action on the coil closely, you will notice that, when the coil is nearly perpendicular to the magnetic flux, the torque action nears zero. -

Synchronous Motor

CHAPTER38 Learning Objectives ➣ Synchronous Motor-General ➣ Principle of Operation ➣ Method of Starting SYNCHRONOUS ➣ Motor on Load with Constant Excitation ➣ Power Flow within a Synchronous Motor MOTOR ➣ Equivalent Circuit of a Synchronous Motor ➣ Power Developed by a Synchronous Motor ➣ Synchronous Motor with Different Excitations ➣ Effect of increased Load with Constant Excitation ➣ Effect of Changing Excitation of Constant Load ➣ Different Torques of a Synchronous Motor ➣ Power Developed by a Synchronous Motor ➣ Alternative Expression for Power Developed ➣ Various Conditions of Maxima ➣ Salient Pole Synchronous Motor ➣ Power Developed by a Salient Pole Synchronous Motor ➣ Effects of Excitation on Armature Current and Power Factor ➣ Constant-Power Lines ➣ Construction of V-curves ➣ Hunting or Surging or Phase Swinging ➣ Methods of Starting ➣ Procedure for Starting a Synchronous Motor Rotary synchronous motor for lift ➣ Comparison between Ç Synchronous and Induction applications Motors ➣ Synchronous Motor Applications 1490 Electrical Technology 38.1. Synchronous Motor—General A synchronous motor (Fig. 38.1) is electrically identical with an alternator or a.c. generator. In fact, a given synchronous machine may be used, at least theoretically, as an alternator, when driven mechanically or as a motor, when driven electrically, just as in the case of d.c. machines. Most synchronous motors are rated between 150 kW and 15 MW and run at speeds ranging from 150 to 1800 r.p.m. Some characteristic features of a synchronous motor are worth noting : 1. It runs either at synchronous speed or not at all i.e. while running it main- tains a constant speed. The only way to change its speed is to vary the supply frequency (because Ns = 120 f / P). -

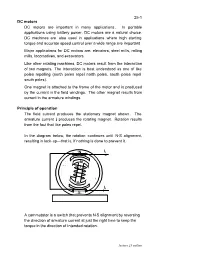

25-1 DC Motors DC Motors Are Important in Many Applications. in Portable Applications Using Battery Power, DC Motors Are a Natural Choice

25-1 DC motors DC motors are important in many applications. In portable applications using battery power, DC motors are a natural choice. DC machines are also used in applications where high starting torque and accurate speed control over a wide range are important. Major applications for DC motors are: elevators, steel mills, rolling mills, locomotives, and excavators. Like other rotating machines, DC motors result from the interaction of two magnets. The interaction is best understood as one of like poles repelling (north poles repel north poles, south poles repel south poles). One magnet is attached to the frame of the motor and is produced by the current in the field windings. The other magnet results from current in the armature windings. Principle of operation The field current produces the stationary magnet shown. The armature current Ia produces the rotating magnet. Rotation results from the fact that like poles repel. In the diagram below, the rotation continues until N-S alignment, resulting in lock-up—that is, if nothing is done to prevent it. A commutator is a switch that prevents N-S alignment by reversing the direction of armature current at just the right time to keep the torque in the direction of intended rotation. lecture 25 outline 25-2 The direction of the field current does not change—changes to the direction of current is confined to the armature. The commutator is a rotating switch. The fixed contacts are carbon brushes spring-loaded against the moving contacts on the shaft. The back EMF on the armature is produced via Faraday’s law.