Download the Complete Volume for 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

TRIUNFO AGÓNICO El Equipo De Querétaro Llegó a 26 Puntos Y Está

EXCELSIOR SÁBADO 9 DE MAYO DE 2015 [email protected] @Adrenalina_Exc EN PLAN GRANDE El mexicano Joakim Soria, quien suma 11 rescates, se apuntó ayer su segunda victoria con Detroit >14-15 TRIUNFO AGÓNICO GALLOS, Foto: AP NADAL, A LA CON VIDA SEMIFINAL El español Rafael El equipo de Querétaro llegó Nadal venció al búlgaro Grigor a 26 puntos y está a la espera Dimitrov y avanzó de poder conseguir un boleto en el Masters de Madrid >22-23 para la liguilla>4-5 Foto: MexsportFoto: ADRENALINA SÁBADO MINUTO A MINUTO: André Marín 3 MULTI 21:30 | con Gerardo Martínez, Adrián Santos vs. Puebla Mauricio Ymay 6 Sierra y Héctor Linares Clausura 2015 / 20:30 horas Ricardo Salazar 8 MEDIA Cruz Azul vs. Leones Negros / Clausura 2015 / 20:30 horas EXCELSIOR Se lo comenté a las 2 SÁBADO 9 DE MAYO DE 2015 @Adrenalina_Exc autoridades de la Universidad y ya tengo permiso de todo. Me apoyarán para publicarlo.” DARÍO VERÓN LIGA MX DEFENSA DE LOS PUMAS PUMAS PREPARA SU LIBRO EL RADAR ADRENALINA Darío Verón dará FUTBOL LIGA MX una vuelta al pasado El capitán de los universitarios quiere dejar un Monterrey vs. Pumas León vs. Tijuana Cruz Azul vs. UdeG Santos vs. Puebla Atlas vs. América 9 y TDN / 19:00 hrs. Fox Sports / 20:06 hrs. 7 y ESPN 2 / 20:30 hrs. 7 y ESPN / 20:30 hrs. 9 y TDN / 21:00 hrs. legado para los jóvenes, pese al mal momento POR ALBERTO ACEVES H. En esa recapitulación de su his- [email protected] toria con el balón, Verón aparta el momento que enfrenta el equipo Darío Verón, el segundo jugador universitario desde hace dos años con más encuentros disputados y medio, cuyos números los desfa- (410) con la camiseta de los Pumas, vorecen tras cinco técnicos, un úl- EL PARTIDO DE BALE NO está por publicar un libro de sus timo lugar en el Apertura 2013 y 35 años en el futbol junto a viejos ami- triunfos en 101 partidos disputados. -

NUEVA SOCIEDAD Número 42 Mayo

NUEVA SOCIEDAD NRO. 100 MARZO-ABRIL 1989. PP 112-121 Un gol lleno de deudas. Uruguay, el fútbol y todo eso karl-ludolf Hübener «Con un abono de 4.000.000 de dólares sobre la deuda externa brasileña fue vendido Romario Farías, astro del fútbol de Brasil, al equipo campeón holandés PSV Eindhoven. Como lo señalara el Jornal do Brasil, la firma holandesa Philips pagó esa suma por el delantero de 24 años de edad con un crédito contra el Banco Central brasileño. Este había sido adquirido previamente por la Philips en el mercado de títulos de la deuda con un descuento de un 25 por ciento». (Información del 22.10.88) Isla de Flores. Una calle de Montevideo no muy lejos del centro. La tarde está avanzada, el calor ha descendido un tanto. Los escasos conductores de vehículos deben disminuir la velocidad en algunos trechos y moverse como si se tratara de un slalom. Por delante hay chicos que corren tras una pelota. Los balones, en su mayoría, están arrugados, blandos o aplastados; los largos años de lucha callejera han terminado, efectivamente, por quitarles el aire. Dos piedras marcan el arco. Las horas pasan sin que decline el ritmo del juego. Los retoños juegan hasta bien entrada la noche corriendo tras los pases; los faroles callejeros reemplazan los focos del estadio. Gritos y llamadas acompañan la batahola. «Peñarol», «Nacional» o «Aguirre». Los chicos se identifican con sus clubes preferidos, se ponen nombres; nombres que recuerdan a los grandes «teman». Los nombres dependen de la coyuntura: algunas veces serán los «aurinegros» de Peñarol, otras los «tricolores» del Nacional - los dos grandes clubes uruguayos, que llevan la voz cantante, allá en la cima - o toman el nombre del que se está batiendo con éxito en una Copa nacional o internacional. -

FIFA Arab Cup 2021 Will Capture Attention of Fans Everywhere: QFA Chief Sheikh Hamad

Cancun World QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune Tour Beach QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune Volleyball silver for Cherif and Ahmed again WEDNESDAY, APRIL 28, 2021 PAGE 14 FIFA Arab Cup 2021 will capture attention of fans everywhere: QFA chief Sheikh Hamad Nawaf Al Temyat, Deputy Vice-President of Saudi Arabia Football Federation holds out Qatar’s name during the FIFA Arab Cup 2021 draw at Katara Opera House on Tuesday. TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK Committee for Delivery & Leg- DOHA acy Secretary-General Hassan Al Thawadi said, “This tour- THE first-ever FIFA Arab Cup nament will see elite teams 2021 will capture the imagi- from across the Arab world nation and attention of fans compete in a FIFA-sanctioned everywhere, said Qatar Foot- tournament for the first time. ball Association President HE A tournament of this magni- Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa bin tude – played exactly a year Ahmed Al Thani on Tuesday. before the World Cup – is sure Sheikh Hamad was among to excite our football crazy the many dignitaries who at- region as we continue prepa- tended the draw ceremony for rations for 2022. We look the firstFIFA Arab Cup 2021 forward to hosting the FIFA FIFA President Gianni Infantino; HE Sheikh Joaan bin Hamad Al Thani, President, Qatar Olympic Committee; HE Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa bin Ahmed Al Thani, President, Qatar at the Katara Opera House. Arab Cup and using the tour- Football Association; Hassan Al Thawadi, Secretary-General, Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy; Nasser Al Khater, CEO, FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022; and others during the “Qatar is very excited to nament to confirm our plans FIFA Arab Cup 2021 draw ceremony at Katara Opera House on Tuesday. -

Qnbfs.Com.Qa Doha, Qatar

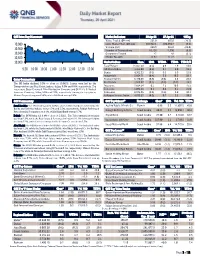

QSE Intra-Day Movement Market Indicators 28 Apr 21 27 Apr 21 %Chg. Value Traded (QR mn) 581.0 693.8 (16.3) 10,980 Exch. Market Cap. (QR mn) 632,952.1 634,394.7 (0.2) Volume (mn) 269.9 355.0 (24.0) 10,960 Number of Transactions 10,426 11,390 (8.5) 10,940 Companies Traded 47 48 (2.1) Market Breadth 14:32 21:22 – 10,920 10,900 Market Indices Close 1D% WTD% YTD% TTM P/E Total Return 21,657.54 (0.3) 0.9 7.9 18.6 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 All Share Index 3,454.08 (0.2) 0.7 8.0 19.3 Banks 4,502.33 (0.1) 0.1 6.0 15.8 Industrials 3,664.71 (0.4) 3.6 18.3 29.1 Qatar Commentary Transportation 3,470.53 (0.9) (0.8) 5.3 23.2 The QE Index declined 0.3% to close at 10,940.6. Losses were led by the Real Estate 1,915.97 (0.4) (0.9) (0.7) 18.2 Transportation and Real Estate indices, falling 0.9% and 0.4%, respectively. Top Insurance 2,654.54 0.3 1.5 10.8 25.5 losers were Qatar Cinema & Film Distribution Company and QLM Life & Medical Telecoms 1,094.26 0.1 0.4 8.3 25.0 Insurance Company, falling 9.9% and 2.0%, respectively. Among the top gainers, Consumer 8,374.05 (0.2) (0.6) 2.9 30.1 Mannai Corporation gained 5.4%, while Ahli Bank was up 2.4%. -

Disillusionment and Years of Conflict, 1884– 1905

chapter 3 Disillusionment and Years of Conflict, 1884– 1905 In 1885, growing tensions between Great Britain and Russia ended a decade of relative ease and no foreign threat to Sweden-Norway. The two great pow- ers ultimately clashed in Afghanistan in the so- called Panjdeh Incident on 30 March 1885. The Russian Empire had been advancing into central and south- ern Asia since 1839, and it pushed on to Afghanistan in the early 1880s. Great Britain considered the advance a threat to India, and quickly entered into dis- cussions about the Afghan border with the Russians in 1882. An agreement on a boundary commission was reached in the summer of 1884, but the Russians kept driving southwards. In March 1885, they crushed the Afghan forces and annexed the Panjdeh district before the commissioners had arrived. The Brit- ish prepared for war, but the issue was eventually settled following the inter- vention of the Amir of Afghanistan.1 Before this solution was reached, however, the strained relations between London and St. Petersburg had transferred to the European territories. With the Baltic Sea forming a natural arena for a war between Russia and Great Britain, Sweden- Norway found itself in the most precarious situation it had been in since the Berlin Congress of 1878. The Swedish-Norwegian government ordered military preparedness when it learned of the confrontation between the British and the Russians, and quickly decided on the rearmament of what was left of its navy and the reinforcement of Gotland’s defences. It also revised its neutrality policy to better support Russia’s interests after Russia’s foreign minister, Nikolay Girs, told the Swedish-Norwegian minister in St. -

The Falling Netanyahu Takes Down a Cantankerous Political Class

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 43rd year No.13954 Saturday MAY 29, 2021 Khordad 8, 1400 Shawwal 17, 1442 Elections is Brighton’s Alireza Steel ingot export Germany recognizes competition to Jahanbakhsh to decide rises 135% in colonial-era massacres in serve people Page 2 on his future Page 3 a month on year Page 4 Namibia as genocide Page 5 Unity is the secret behind the Resistance’s victories: Amir-Abdollahian TEHRAN - Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, the resistance and steadfastness victory could special aide to the speaker of the Iranian be achieved. This victory sent an important Parliament on international affairs, has re- message that the Zionist enemy only under- flected on the secret behind the recent victory stands the language of force and resistance,” of the Palestinian resistance against Israel. he told the Lebanese Al-Ahed News. Amir-Abdollahian said the 2006 victo- The Iranian diplomat added, “This ry of the Lebanese resistance movement victory and other victories achieved by against Israel raised faith in the resistance the resistance, especially the victory of and sent a message that Israel understands July 2006, were achieved in light of the only the language of power. unity of the Lebanese people and the gold- “The flight of the Zionist entity from en equation in Lebanon – the army, the southern Lebanon raised faith in the resist- people, and the resistance. Crabs in ance among the Lebanese, and that through Continued on page 3 Tehran, Moscow confer on joint investment in agricultural sector TEHRAN – Iranian Agriculture Minis- investment in various agricultural fields. -

ISLAMIC NARRATIVE and AUTHORITY in SOUTHEAST ASIA 1403979839Ts01.Qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page Ii

1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page i ISLAMIC NARRATIVE AND AUTHORITY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page ii CONTEMPORARY ANTHROPOLOGY OF RELIGION A series published with the Society for the Anthropology of Religion Robert Hefner, Series Editor Boston University Published by Palgrave Macmillan Body / Meaning / Healing By Thomas J. Csordas The Weight of the Past: Living with History in Mahajanga, Madagascar By Michael Lambek After the Rescue: Jewish Identity and Community in Contemporary Denmark By Andrew Buckser Empowering the Past, Confronting the Future By Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart Islam Obscured: The Rhetoric of Anthropological Representation By Daniel Martin Varisco Islam, Memory, and Morality in Yemen: Ruling Families in Transition By Gabrielle Vom Bruck A Peaceful Jihad: Negotiating Identity and Modernity in Muslim Java By Ronald Lukens-Bull The Road to Clarity: Seventh-Day Adventism in Madagascar By Eva Keller Yoruba in Diaspora: An African Church in London By Hermione Harris Islamic Narrative and Authority in Southeast Asia: From the 16th to the 21st Century By Thomas Gibson 1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page iii Islamic Narrative and Authority in Southeast Asia From the 16th to the 21st Century Thomas Gibson 1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page iv ISLAMIC NARRATIVE AND AUTHORITY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA © Thomas Gibson, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. -

Goalden Times: October, 2011 Edition

Goalden Times October 2011 Page 0 qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyu Goalden Times Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: GOALden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes October 2011 Page 1 Goalden Times | Edition III | First Whistle…………4 Goalden Times is a ‘rising star’. Watch this space... Garrincha – The Forgotten Legend …………5 Deepanjan Deb pays a moving homage to his hero in the month of his birth Last Rays of Sunshine Before the Clouds of War…………9 In our Retrospective feature - continuing our journey through the history of the World Cup, Kinshuk Biswas goes back to the last World Cup before World War II 1911 – A Seminal Win …………16 Kaushik Saha travels back in time to see how a football match influences a nation’s fight for freedom Amarcord: My Life as a Calcio Fan…………20 We welcome Annalisa D’Antonio to share her love of football and growing up stories of fun, frolic and Calcio This Month That Year…………23 This month in Football History Rifle, Regime, Revenge and the Ugly Game…………27 Srinwantu Dey captures a vignette of stories where football no longer remained ‘the beautiful game’ Scouting Network…………33 A regular feature - where we profile an upcoming talent of the football world. -

The Hadrami Diaspora: Community-Building on the Indian Ocean Rim by Leif Manger (Review)

The Hadrami Diaspora: Community-Building on the Indian Ocean Rim by Leif Manger (review) Daniel Martin Varisco Mashriq & Mahjar: Journal of Middle East and North African Migration Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, 2013, (Review) Published by Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/779786/summary [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 20:00 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Mashriq & Mahjar 1, no. 2 (2013), 130-133 ISSN 2169-4435 LEIF MANGER, The Hadrami Diaspora: Community-Building on the Indian Ocean Rim (New York: Berghahn Books, 2010). Pp. 220. $60.00 cloth. REVIEWED BY DANIEL MARTIN VARISCO, Department of Anthropology, Hofstra University, email: [email protected] “The present book is thus the end result of a rather long anthropological journey, filled with interesting moments of discovery but also a feeling of anxiety as I struggled with my inclination to deal with the ‘totality’ of Hadarami (sic) immigration history: My anthropological instincts told me to settle for a discussion of things less speculative, more focused on stories in which we can see real people” (x). Before I prepared to live in North Yemen in 1978 to conduct ethnographic fieldwork on tradition irrigation and water rights, I benefited greatly from earlier ethnographic work on irrigation in South Yemen’s Hadramawt from Abdulla Bujra’s The Politics of Stratification: A Study of Political change in a South Arabian Town.1 Based on a year’s research in the town of Hureidah in 1962-63, Bujra provided one of the few on-the-ground anthropological studies of Yemen at the time. -

The Socialist Calculation Debate and New Socialist Models in Light of a Contextual Historical Materialist Interpretation

THE SOCIALIST CALCULATION DEBATE AND NEW SOCIALIST MODELS IN LIGHT OF A CONTEXTUAL HISTORICAL MATERIALIST INTERPRETATION by Adam Balsam BSc [email protected] Supervised by Justin Podur BSc MScF PhD A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada December 11, 2020 Table of Contents The Statement of Requirements for the Major Paper ................................................................................. iii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iv Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................... vi Section I: Introduction, Context, Framework and Methodology .................................................................. 1 Preamble ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Context of this Investigation ................................................................................................................. 5 The Possibilities of Socialist Models .................................................................................................. -

On Stalin's "Economic Problems"

ON STALIN’S “Economic Problems” (part one) IRISH COMMUNIST ORGANISATION CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND (Dobb on his Predecessors; Brutzkus on his Colleagues; An ‘Unpleasant Piece of Work’; The Development of Oscar Lange….) WHAT IS POLITICAL ECONOMY? (Yaroshenko; A Gangster From Chicago.) THE QUESTION OF ECONOMIC CALCULATION (Von Mises and Brutzkus; Trotsky; Dobb – Precursor of Yaroshenko; Labour and Socialism; Ota Sik: The New Ecclesiastes; Lenin On Communist Labour.) * IRISH COMMUNIST ORGANISATION First Edition: May 1968 ****** Reprinted Dec. 1969 INTRODUCTION On October 18th 1952, George Matthews (now editor of the Morning Star) wrote, concerning Stalin’s “Economic Problems of Socialism in the U.S.S.R.”: “As we write only short extracts from Stalin’s articles are available in English… It is, however, already clear that it is an immensely important, fundamental work.” (‘Stalin’s 1 New Basic Work On Marxism’. World News and Views – forerunner of “Comment”, 18- 10-1952) Matthews and his ilk did not need (in 1952) to know what Stalin had actually written in “Economic Problems” in order to know that (in 1952) the furtherance of their careers in the Communist Party of Great Britain required that they should hail it as a brilliant development of Marxist theory. Stalin died in 1953. Within a few years of his death Matthews and his kind became convinced that the furtherance of their careers depended on the suppression of “Stalin’s New Basic Work On Marxism”. No attempts were made to actually refute the analysis made in “Economic Problems”. That would have been far too dangerous a thing for opportunists (shallow, careerist opportunists of the most trivial kind) to attempt.