Binding Ochre to Theory Simone E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brandоаlionоаsuede Desert Poncho

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 Free Knitting Pattern from Lion Brand Yarn Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 SKILL LEVEL: Intermediate (Level 3) SIZE: Small, Medium, Large Width 10 (10½, 11)" [25.5 (26.5, 28) cm] at neck; 60 ½ (64, 68½)" [153.5 (162.5, 174) cm] at lower edge Length 23 (25½, 28)" [58.5 (65, 71) cm] at sides; 30 (32 ½, 35)" [76 (82.5, 89) cm] at points Note: Pattern is written for smallest size with changes for larger sizes in parentheses. When only one number is given, it applies to all sizes. To follow pattern more easily, circle all numbers pertaining to your size before beginning. CORRECTIONS: None as of Jun 30, 2016. To check for later updates, click here. MATERIALS • 210126 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Coffee 6 (6, 7) Balls (A) • 210125 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Mocha *Lion® Suede (Article #210). 100% Polyester; package size: Solids: 3.00 3 (4, 4) Balls (B) oz./85g; 122 yd/110m balls • 210098 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Ecru Prints: 3:00 oz/85g; 111 yd/100m balls 3 (4, 4) Balls (C) • Lion Brand Crochet Hook Size H8 (5 mm) • Lion Brand Split Ring Stitch Markers • Additional Materials • Size 8 [5 mm] 24" [60 cm] circular needles • Size 8 [5 mm] 40" [100 cm] circular needles or size needed to obtain gauge • Size 6 [4 mm] 16" [40 cm] circular needles GAUGE: 14 sts + 23 rnds = 4" [10 cm] in Stockinette st (knit every rnd) on larger needle. -

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (Revised 3/15/19)

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (revised 3/15/19) Every effort will be made to update this list on a seasonal basis. List subject to change without notice due to ongoing Zoo improvements or animal care. North American Wetlands: Muted Swans Mallard Duck Wild Turkey (off Exhibit) Egyptian Goose American White pelican (located in flamingo exhibit during winter months) Bald Eagle Wild Way Trail: (seasonal) Red-necked wallaby Prehensile tail porcupine Ring-tailed lemur Howler Monkey Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Red’s Hobby Farm: Domestic goats Domestic sheep Chickens Pied Crow Common Barn Owl Budgerigar (seasonal) Bali Mynah (seasonal) Crested Wood Partridge (seasonal) Nicobar Pigeon (seasonal) John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Frogs: Smokey Jungle frogs Chacoan Horned frog Tiger-legged monkey frog Vietnamese Mossy frog Mission Golden-eyed Tree frog Golden Poison dart frog American bullfrog Multiple species of poison dart frog North America: Golden Eagle North American River Otter Painted turtle Blanding’s turtle Common Map turtle Eastern Box turtle Red-eared slider Snapping turtle Canada Lynx Brown Bear Mountain Lion/Cougar Snow Leopard South America: South American tapir Crested screamer Maned Wolf Chilean Flamingo Fulvous Whistling Duck Chiloe Wigeon Ringed Teal Toco Toucan (opening in late May) White-faced Saki monkey John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Africa: Chimpanzee Lion African ground hornbill Egyptian Geese Eastern Bongo Warthog Cape Porcupine (off exhibit) Von der Decken’s hornbill (off exhibit) Forest Realm: Amur Tigers Red Panda -

Study of Fragments of Mural Paintings from the Roman Province Of

Study of fragments of mural paintings from the Roman province of Germania Superior Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree Doctor rer. nat. of the Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany by Rafaela Debastiani Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany 2016 Name of Dean: Prof. Dr. Tim Freytag Name of Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Michael Fiederle Name of 2nd Reviewer: PD Dr. Andreas Danilewsky Date of thesis' defense: 03.02.2017 “The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled” Plutarch Contents Nomenclature ........................................................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgment ................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 5 Zusammenfassung ................................................................................................................ 7 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 9 2. Analytical techniques in the non-destructive analyses of fragments of mural paintings ..13 2.1 X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy ..........................................................................13 2.1.1 Synchrotron-based scanning macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) .................17 -

Cortinarius Caperatus (Pers.) Fr., a New Record for Turkish Mycobiota

Kastamonu Üni., Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, 2015, 15 (1): 86-89 Kastamonu Univ., Journal of Forestry Faculty Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr., A New Record For Turkish Mycobiota *Ilgaz AKATA1, Şanlı KABAKTEPE2, Hasan AKGÜL3 Ankara University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, 06100, Tandoğan, Ankara Turkey İnönü University, Battalgazi Vocational School, TR-44210 Battalgazi, Malatya, Turkey Gaziantep University, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Arts, 27310 Gaziantep, Turkey *Correspending author: [email protected] Received date: 03.02.2015 Abstract In this study, Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr. belonging to the family Cortinariaceae was recorded for the first time from Turkey. A short description, ecology, distribution and photographs related to macro and micromorphologies of the species are provided and discussed briefly. Keywords: Cortinarius caperatus, mycobiota, new record, Turkey Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr., Türkiye Mikobiyotası İçin Yeni Bir Kayıt Özet Bu çalışmada, Cortinariaceae familyasına mensup Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr. Türkiye’den ilk kez kaydedilmiştir. Türün kısa deskripsiyonu, ekolojisi, yayılışı ve makro ve mikro morfolojilerine ait fotoğrafları verilmiş ve kısaca tartışılmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Cortinarius caperatus, Mikobiyota, Yeni kayıt, Türkiye Introduction lamellae edges (Arora, 1986; Hansen and Cortinarius is a large and complex genus Knudsen, 1992; Orton, 1984; Uzun et al., of family Cortinariaceae within the order 2013). Agaricales, The genus contains According to the literature (Sesli and approximately 2 000 species recognised Denchev, 2008, Uzun et al, 2013; Akata et worldwide. The most common features al; 2014), 98 species in the genus Cortinarius among the members of the genus are the have so far been recorded from Turkey but presence of cortina between the pileus and there is not any record of Cortinarius the stipe and cinnamon brown to rusty brown caperatus (Pers.) Fr. -

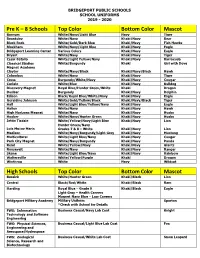

8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot

BRIDGEPORT PUBLIC SCHOOLS SCHOOL UNIFORMS 2019 - 2020 Pre K – 8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot Barnum White/Navy/Light Blue Navy Tiger Beardsley White/Navy Khaki/Navy Bear Black Rock White/Gold/Dark Blue Khaki/Navy Fish Hawks Blackham White/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Eagle Bridgeport Learning Center Various Colors Khaki/Navy Eagle Bryant White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger César Batalla White/Light Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Barracuda Classical Studies White/Burgundy Khaki Girl with Dove Magnet Academy Claytor White/Navy/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Hawk Columbus White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger Cross Burgundy/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Curiale White/Blue Khaki/Navy Bulldog Discovery Magnet Royal Blue/Hunter Green/White Khaki Dragon Dunbar Burgundy Khaki/Navy Dolphin Edison Black/Royal Blue/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Geraldine Johnson White/Gold/Yellow/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Tiger Hall White/Light Blue/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Hallen White/Navy Khaki/Navy Hawk High Horizons Magnet White/Navy Khaki/Navy Husky Hooker White/Navy/Hunter Green Khaki/Navy Husky Jettie Tisdale White/Yellow/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Lion Hunter Green/Navy Luis Muñoz Marín Grades 7 & 8 – White Khaki/Navy Lion Madison White/Navy/Burgundy/Light Grey Khaki/Navy Mustang Multicultural White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Park City Magnet White/Navy/Burgundy Khaki/Navy Panda Read White/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Giants Roosevelt White/Navy Khaki/Navy Ranger Skane White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Rainbow Waltersville White/Yellow/Purple Khaki Dragon Winthrop White Navy Wildcat -

Colours in Nature Colours

Nature's Wonderful Colours Magdalena KonečnáMagdalena Sedláčková • Jana • Štěpánka Sekaninová Nature is teeming with incredible colours. But have you ever wondered how the colours green, yellow, pink or blue might taste or smell? What could they sound like? Or what would they feel like if you touched them? Nature’s colours are so wonderful ColoursIN NATURE and diverse they inspired people to use the names of plants, animals and minerals when labelling all the nuances. Join us on Magdalena Konečná • Jana Sedláčková • Štěpánka Sekaninová a journey to discover the twelve most well-known colours and their shades. You will learn that the colours and elements you find in nature are often closely connected. Will you be able to find all the links in each chapter? Last but not least, if you are an aspiring artist, take our course at the end of the book and you’ll be able to paint as exquisitely as nature itself does! COLOURS IN NATURE COLOURS albatrosmedia.eu b4u publishing Prelude Who painted the trees green? Well, Nature can do this and other magic. Nature abounds in colours of all shades. Long, long ago people began to name colours for plants, animals and minerals they saw them in, so as better to tell them apart. But as time passed, ever more plants, animals and minerals were discovered that reminded us of colours already named. So we started to use the names for shades we already knew to name these new natural elements. What are these names? Join us as we look at beautiful colour shades one by one – from snow white, through canary yellow, ruby red, forget-me-not blue and moss green to the blackest black, dark as the night sky. -

PIGMENTS Pigments Can Be Used for Colouring and Tinting Paints, Glazes, Clays and Plasters

PIGMENTS Pigments can be used for colouring and tinting paints, glazes, clays and plasters. About Pigments About Earthborn Pigments Get creative with Earthborn Pigments. These natural earth and mineral powders provide a source of concentrated colour for paint blending and special effects. With 48 pigments to choose from, they can be blended into any Earthborn interior or exterior paint to create your own unique shade of eco friendly paint. Mixed with Earthborn Wall Glaze, the pigments are perfect for decorative effects such as colour washes, dragging, sponging and stencilling. Some even contain naturally occurring metallic flakes to add extra dazzle to your design. Earthborn Pigments are fade resistant and can be mixed with Earthborn Claypaint and Casein Paint. Many can also be mixed with lime washes, mortars and our Ecopro Silicate Masonry Paint. We have created this booklet to show pigments in their true form. Colour may vary dependant on the medium it is mixed with. Standard sizes 75g, 500g Special sizes 50g and 400g (Mica Gold, Mangan Purple, Salmon Red and Rhine Gold only) Ingredients Earth pigments, mineral pigments, metal pigments, trisodium citrate. How to use Earthborn Pigments The pigments must be made into a paste before use as follows: For Silicate paint soak pigment in a small amount of Silicate primer and use straightaway. For Earthborn Wall Glaze, Casein or Claypaint soak pigment in enough water to cover the powder, preferably overnight, and stir to create a free-flowing liquid paste. When mixing pigments into any medium, always make a note of the amounts used. Avoid contact with clothing as pigments may permanently stain fabrics. -

Colored Cements for Masonry

Colored Cements for Masonry Make an Impact with Colored Mortar Continuing Education Provider Your selection of colored mortar can make a vivid impact on the look of Essroc encourages continuing education for architects your building. Mortar joints comprise an average of 20 percent of a brick and is a registered Continuing Education Provider of the wall’s total surface. Your selection American Institute of Architects. of i.design flamingo-BRIXMENT can dramatically enhance this surface with an eye-catching spectrum of color choices. First in Portland Cement Masonry Products that Endure the Test of Time i.design flamingo-BRIXMENT color masonry cements are manufactured First in Masonry Cement to the most exacting standards in our industry and uniquely formulated to provide strength, stability and color fastness to endure for generations. First in Colored Masonry Cement Our products are manufactured with the highest-quality iron oxide pigments, which provide consistent color quality throughout the life of the Essroc recommends constructing a sample panel prior to construction structure. All products are manufactured to meet the appropriate ASTM and/or placing an order for color. Field conditions and sand will affect specifications. the finished color. Strong on Service i.design flamingo-BRIXMENT products are distributed by a network of dealers and backed by regional Customer Support Teams. Essroc Essroc Customers also enjoy 24/7 service through www.MyEssroc.com. This Italcementi Group Essroc e-business center provides secure, instant communication -

Gamblin Provides Is the Desire to Help Painters Choose the Materials That Best Support Their Own Artistic Intentions

AUGUST 2008 Mineral and Modern Pigments: Painters' Access to Color At the heart of all of the technical information that Gamblin provides is the desire to help painters choose the materials that best support their own artistic intentions. After all, when a painting is complete, all of the intention, thought, and feeling that went into creating the work exist solely in the materials. This issue of Studio Notes looks at Gamblin's organization of their color palette and the division of mineral and modern colors. This visual division of mineral and modern colors is unique in the art material industry, and it gives painters an insight into the makeup of pigments from which these colors are derived, as well as some practical information to help painters create their own personal color palettes. So, without further ado, let's take a look at the Gamblin Artists Grade Color Chart: The Mineral side of the color chart includes those colors made from inorganic pigments from earth and metals. These include earth colors such as Burnt Sienna and Yellow Ochre, as well as those metal-based colors such as Cadmium Yellows and Reds and Cobalt Blue, Green, and Violet. The Modern side of the color chart is comprised of colors made from modern "organic" pigments, which have a molecular structure based on carbon. These include the "tongue- twisting" color names like Quinacridone, Phthalocyanine, and Dioxazine. These two groups of colors have unique mixing characteristics, so this organization helps painters choose an appropriate palette for their artistic intentions. Eras of Pigment History This organization of the Gamblin chart can be broken down a bit further by giving it some historical perspective based on the three main eras of pigment history – Classical, Impressionist, and Modern. -

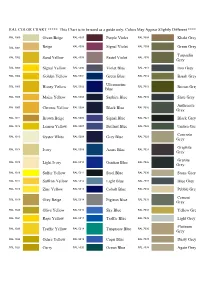

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India's Wall Paintings

heritage Review A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India’s Wall Paintings Anjali Sharma 1 and Manager Rajdeo Singh 2,* 1 Department of Conservation, National Museum Institute, Janpath, New Delhi 110011, India; [email protected] 2 National Research Laboratory for the Conservation of Cultural Property, Aliganj, Lucknow 226024, India * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Iron-containing earth minerals of various hues were the earliest pigments of the prehistoric artists who dwelled in caves. Being a prominent part of human expression through art, nature- derived pigments have been used in continuum through ages until now. Studies reveal that the primitive artist stored or used his pigments as color cakes made out of skin or reeds. Although records to help understand the technical details of Indian painting in the early periodare scanty, there is a certain amount of material from which some idea may be gained regarding the methods used by the artists to obtain their results. Considering Indian wall paintings, the most widely used earth pigments include red, yellow, and green ochres, making it fairly easy for the modern era scientific conservators and researchers to study them. The present knowledge on material sources given in the literature is limited and deficient as of now, hence the present work attempts to elucidate the range of earth pigments encountered in Indian wall paintings and the scientific studies and characterization by analytical techniques that form the knowledge background on the topic. Studies leadingto well-founded knowledge on pigments can contribute towards the safeguarding of Indian cultural heritage as well as spread awareness among conservators, restorers, and scholars. -

Pigments Suitable for Encaustic

Pigments suitable for Encaustic For encaustic, pigments are melted into wax or a wax-resin-mixture. It is very important not to use toxic pigments with this technique. Pigments used for encaustic must not contain lead, arsenic or cadmium. The following list complies pigments which are heat-stable enough for this technique. However, the pigments should not be heated over the melting point of the wax and they should not be burnt. The pigments listed here are not safe for use in candle making. We recommend tests prior to the final application. Caution: Heated wax is a fire hazard and should never be left unattended. Wax vapors and fumes are hazardous for the health and should not be inhaled. An exhaust system should be installed to pull out wax vapors. Kremer-made and historic pigments 10000 - 10010 Smalt 11283 Alba Albula 10060 Egyptian Blue 11300 Red Jasper 10071 - 10072 Han-Blue 11350 Côte d'Azur Violet 10074 - 10075 Han-Purple 11360 Brown red slate 104200 Sodalite 11390 - 11392 Jade 10500 - 10580 Lapis Lazuli 11400 - 11401 Rock Crystal 11000 - 11010 Verona Green Earth 11420 - 11424 Fuchsite 11100 Bavarian Green Earth 11530 Gold Ochre from Saxony 11110 – 11111 Russische Grüne Erde 11572 - 11577 Burgundy Ochres 11140 - 11141 Aegirine 11584 - 11585 Spanish Red Ochre 11150 Epidote 11620 Brown Earth from Otranto 11200 Green Jasper 116420-116441 Moroccan Ochres 11272-11276 Ochres from Andalusia 11670 Onyx Black 11282 Nero Bernino 11674 Obsidian Black Synthetic-organic Pigments 23000 Phthalo Green Dark 23340 Isoindole Yellow 23010 Phthalo Green,