The First Emperor and His Army in Imagery and Sculpture 255

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(S): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(s): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 3, (Sep., 1994), pp. 511-534 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046042 Accessed: 17/04/2008 11:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Eugene Yuejin Wang a 1 Jian (looking/mirror), stages of development of ancient ideograph (adapted from Zhongwendazzdian [Encyclopedic dictionary of the Chinese language], Taipei, 1982, vi, 9853) History as Mirror: Trope and Artifact people. -

THE INDIVIDUAL and the STATE: STORIES of ASSASSINS in EARLY IMPERIAL CHINA by Fangzhi Xu

THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE STATE: STORIES OF ASSASSINS IN EARLY IMPERIAL CHINA by Fangzhi Xu ____________________________ Copyright © Fangzhi Xu 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 Xu 2 Xu 3 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 1: Concepts Related to Assassins ............................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: Zhuan Zhu .............................................................................................................. 17 Chapter 3: Jing Ke ................................................................................................................... 42 Chapter 4: Assassins as Exempla ............................................................................................. 88 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 96 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... 100 Xu 4 Abstract In my thesis I try to give a new reading about the stories of assassins in the -

The Stage Art of Ng Kwan Lai

A Synthesis of Lyrical Excellence & Martial Agility – The Stage Art of Ng Kwan Lai Learning From Great Masters Born Ng Wan, a native of Zhongshan in the province of Guangdong, Ng Kwan Lai grew up in Shanghai, and it was while she was being educated there that she became fascinated by traditional dramatic performances. Arriving in Hong Kong with her family in 1952, she enrolled at the Hong Kong Academy of Cantonese Opera the following year to study under the renowned performer Chan Fei Nung. A hard-working student who realized that the martial arts and acrobatic performances of Beijing Opera held a greater appeal, she went on to learn stage martial arts under the father-and-son team of Kay Choi Fun and Kay Yuk Kun, the well-known Beijing Opera masters. Her concentrated efforts quickly bore fruit as her performances gained in skill and credibility. To improve her vocal presentation, she turned to Cantonese Opera singing coaches Wan Chi Chung and Lam Siu Lau and then took lessons in ancient melodies from Lui Man Shing. The tutelage of these famous musicians introduced her to the art of singing, and her voice began to take on a memorable brilliance and resonance. Guided by these great masters, Ng received balanced training in stylistic and vocal performance, and this paved the way for her success in the roles of the dou ma dan (the female martial role), the tsing yi (the gentle young woman who suffers a distressing fate and ends up destitute) and the kwei mun dan (the girl from an affluent and respectable family). -

The Hundred Surnames: a Pinyin Index

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 12:59 Page 3 The hundred surnames: a Pinyin index Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Ai Ai Ai Zidong Cong Ts’ung Zong Cong Zhen Ai Ai Ai Songgu Cui Ts’ui Cui Jian, Cui Yanhui An An An Lushan Da Ta Da Zhongguang Ao Ao Ao Taosun, Ao Jigong Dai Tai Dai De, Dai Zhen Ba Pa Ba Su Dang Tang Dang Jin, Dang Huaiying Bai Pai Bai Juyi, Bai Yunqian Deng Teng Tang, Deng Xiaoping, Bai Pai Bai Qian, Bai Ziting Thien Deng Shiru Baili Paili Baili Song Di Ti Di Xi Ban Pan Ban Gu, Ban Chao Diao Tiao Diao Baoming, Bao Pao Bao Zheng, Bao Shichen Diao Daigao Bao Pao Bao Jingyan, Bao Zhao Ding Ting Ding Yunpeng, Ding Qian Bao Pao Bao Xian Diwu Tiwu Diwu Tai, Diwu Juren Bei Pei Bei Yiyuan, Bei Qiong Dong Tung Dong Lianghui Ben Pen Ben Sheng Dong Tung Dong Zhongshu, Bi Pi Bi Sheng, Bi Ruan, Bi Zhu Dong Jianhua Bian Pien Bian Hua, Bian Wenyu Dongfang Tungfang Dongfang Shuo Bian Pien Bian Gong Dongguo Tungkuo Dongguo Yannian Bie Pieh Bie Zhijie Dongmen Tungmen Dongmen Guifu Bing Ping Bing Yu, Bing Yuan Dou Tou Dou Tao Bo Po Bo Lin Dou Tou Dou Wei, Dou Mo, Bo Po Bo Yu, Bo Shaozhi Dou Xian Bu Pu Bu Tianzhang, Bu Shang Du Tu Du Shi, Du Fu, Du Mu Bu Pu Bu Liang Du Tu Du Yu Cai Ts’ai Chai, Cai Lun, Cai Wenji, Cai Ze Du Tu Du Xia Chua, Du Tu Du Qiong Choy Duan Tuan Duan Yucai Cang Ts’ang Cang Xie Duangan Tuankan Duangan Tong Cao Ts’ao Tso, Tow Cao Cao, Cao Xueqin, Duanmu Tuanmu Duanmu Guohu Cao Kun E O E -

The Contingency of China's Imperial Unity: Assassins Attack the First King Of

THE CONTINGENCY OF CHINA’S IMPERIAL UNITY Assassins Attack the First King of Qin by Emily M. Hill The First Emperor of China Co-directed by Tony Ianzelo and Liu Haoxue Qin and his achievements, each also highlights the costs and condi- Distributed by Slingshot Entertainment (www.slingshotent.com) tions of the founder’s conquests by featuring failed attempts to 1988. 40 Minutes assassinate him. The Emperor’s Shadow During one of the first classes of the course, students watch The First Emperor of China (1988). An informative dramatized docu- Directed by Zhou Xiaowen mentary, the film lacks aesthetic appeal but is an engaging starting Distributed by Fox Lorber Films (www.foxlorber.com) point for exploration of early Chinese history. Certain inaccuracies 1996. 123 Minutes should be pointed out in the course of class discussion; the Great The Emperor and the Assassin Wall as it stands today, for instance, is not the same as the system of Directed by Chen Kaige fortifications constructed of pressed earth that existed in Qin times. Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics (www.sonyclassics.com) Moreover, there is no good evidence for the legend that in 212 BCE 1999. 161 Minutes the First Emperor of Qin flew into a rage and ordered that 460 Hero learned men be buried alive. A highlight of The First Emperor of Directed by Zhang Yimou China is the dramatization of the attempt by Jing Ke to assassinate Distributed by Edko Films Ltd. (www.herothemovie.com) the King of Qin. The failed attempt, which occurred in 227 BCE, is 2002 (US release in August of 2004). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced fromm icrofilm the master. UMI films the text directly firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be ft’om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9218985 Spatialization in the ‘‘Shiji” Jian, Xiaobin, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 Copyright ©1992 by Jian, Xiaobin. All rights reserved. -

The Qin Revolution

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 4.1 THE QIN DYNASTY Background The state of Qin was the westernmost of the patrician states of China, and had originally been viewed as a non-Chinese tribe. Its ruler was granted an official Zhou title in the eighth century B.C. in consequence of political loyalty and military service provided to the young Zhou king in Luoyang, the new eastern capital, at a time when the legitimate title to the Zhou throne was in dispute after the fall of the Western Zhou. The sustained reign of Duke Mu during the seventh century did much to elevate the status of Qin among the community of patrician states, but the basic prejudice against Qin as semi-“barbarian” persisted. Never during the Classical period did Qin come to be viewed as fully Chinese in a cultural sense. Qin produced great warriors, but no great leaders after Duke Mu, no notable thinkers or literary figures. Its governmental policies were the most progressive in China, but these were all conceived and implemented by men from the east who served as “Alien Ministers” at the highest ranks of the Qin court, rather than by natives of Qin. Yet Qin aspired to full membership in the Chinese cultural sphere. Li Si, the Prime Minister who shepherded Qin’s conquest of the other states, captured what must have been a widely held view of Qin in a memorial he sent to the king before his elevation to highest power. “To please the ear by thumping a water jug, banging a pot, twanging a zither, slapping a thigh and singing woo-woo! – that is the native music of Qin. -

King Wen's Tower

King Wen’s Tower Game in Progress by Emily Care Boss Black & Green Games L 2014 GM Checklist • Welcome everyone • Second Round (and on until 1 Kingdom Left) • Overview of Game Intrigue Scene: GM choose Kingdom Warring States Period Scenario Rules Tower Phase Token hand off (all Kingdoms) Choose Kingdom Tile • Setup Conquering Scene Map and Kingdom Sheets Kingdom Player choose: Battle or Surrender Players choose Kingdoms Questions Tokens, Cards, Tiles and Reference sheets • Last Kingdom • Introduction Optonal Intrigue Scene: War Council of Qin Last Kingdom Player: Ying Zheng Kingdom Descriptions Tower Phase Conquering Scene for unplayed No Tokens Kingdoms (1 question each) Play Kingdom Tile Conquering Scene • First Round: Battle or Surrender Questions Intrigue Scene Horizontal & Vertical Alliances • Debriefing Tower Phase King Wen Sequence Token hand off (GM breaks ties) Find Kingdom Tile Hexagram Choose Kingdom Tile Answer Question Conquering Scene History Kingdom Player chose: Share historical timeline Battle or Surrender Questions Materials • Game rules • Tokens (7) use counters, coins or stones, etc. Warring States Map • • Kingdom Tiles (12) Two per Kingdom, cut out GM Reference Sheets (pp. 13 - 16) • • Qin Agent Cards (12) cut out Kingdom Sheets (7) One per Kingdom • • King Wen Sequence Table - Questions Player Reference (7) Hundred Schools, Stratagems • • Blank paper - name cards for Intrigue Scenes 2 Table of Contents GM Checklist. 2 About the Game. 4 Scenario Rules. 5 Early Chinese History. 8 Hundred Schools of Thought. 9 Stratagems. .10 Map of the Seven Kingdoms. 11 Kingdoms of the Late Warring States Period. .12 Intrigue Scene Summaries. .13 Kingdom Summary Sheets: Qin (GM). 15 GM Master list of Battle & Surrender Scenes. -

The Hundred Surnames: a Pinyin Index

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 12:59 Page 3 The hundred surnames: a Pinyin index Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Ai Ai Ai Zidong Cong Ts’ung Zong Cong Zhen Ai Ai Ai Songgu Cui Ts’ui Cui Jian, Cui Yanhui An An An Lushan Da Ta Da Zhongguang Ao Ao Ao Taosun, Ao Jigong Dai Tai Dai De, Dai Zhen Ba Pa Ba Su Dang Tang Dang Jin, Dang Huaiying Bai Pai Bai Juyi, Bai Yunqian Deng Teng Tang, Deng Xiaoping, Bai Pai Bai Qian, Bai Ziting Thien Deng Shiru Baili Paili Baili Song Di Ti Di Xi Ban Pan Ban Gu, Ban Chao Diao Tiao Diao Baoming, Bao Pao Bao Zheng, Bao Shichen Diao Daigao Bao Pao Bao Jingyan, Bao Zhao Ding Ting Ding Yunpeng, Ding Qian Bao Pao Bao Xian Diwu Tiwu Diwu Tai, Diwu Juren Bei Pei Bei Yiyuan, Bei Qiong Dong Tung Dong Lianghui Ben Pen Ben Sheng Dong Tung Dong Zhongshu, Bi Pi Bi Sheng, Bi Ruan, Bi Zhu Dong Jianhua Bian Pien Bian Hua, Bian Wenyu Dongfang Tungfang Dongfang Shuo Bian Pien Bian Gong Dongguo Tungkuo Dongguo Yannian Bie Pieh Bie Zhijie Dongmen Tungmen Dongmen Guifu Bing Ping Bing Yu, Bing Yuan Dou Tou Dou Tao Bo Po Bo Lin Dou Tou Dou Wei, Dou Mo, Bo Po Bo Yu, Bo Shaozhi Dou Xian Bu Pu Bu Tianzhang, Bu Shang Du Tu Du Shi, Du Fu, Du Mu Bu Pu Bu Liang Du Tu Du Yu Cai Ts’ai Chai, Cai Lun, Cai Wenji, Cai Ze Du Tu Du Xia Chua, Du Tu Du Qiong Choy Duan Tuan Duan Yucai Cang Ts’ang Cang Xie Duangan Tuankan Duangan Tong Cao Ts’ao Tso, Tow Cao Cao, Cao Xueqin, Duanmu Tuanmu Duanmu Guohu Cao Kun E O E -

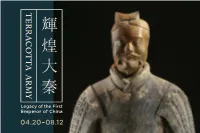

View Terracotta Gallery Guide

04.20–08.12 Welcome to Terracotta Army: Legacy of the First Emperor of China at Your Cincinnati Art Museum. In 1974, farmers digging a well in the small village of Xi’an, in Northwest China, stumbled upon fragments of terracotta figures. At the time, they were not aware that they had just uncovered one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. The objects excavated include nearly 8,000 life-size warriors, chariots, and horses created to accompany their ruler into the afterlife. Presented in three sections, Terracotta Army: Legacy of the First Emperor of China, a partnership between the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, features major objects from the First Emperor’s mausoleum complex in Xi’an and other Qin tombs. These objects have been brought together to tell the story of the First Emperor’s rise to power, the history of the Qin state, and his ultimate quest for immortality. Timeline of the First Emperor of Qin DATE EVENTS 227 BCE AGE 33: Survived attempted 259 BCE Born Ying Zheng in Handan, assassination by Jing Ke Zhao state 225 BCE AGE 35: Defeated Wei state 251 BCE AGE 9: Returned to Qin state 223 BCE AGE 37: Defeated Chu state 250 BCE AGE 10: Appointed as Crown Prince of Qin State 222 BCE AGE 38: Defeated Yan state 246 BCE AGE 13: Ascended the throne as King Ying Zheng of Qin; 221 BCE AGE 39: Defeated Qi state; Ordered construction of his Unified the country and mausoleum at base of Mount Li proclaimed himself First Emperor or Qin Shihuang; Standardization of currency, 241 BCE -

William Woodville Rockhill and His Chinese Language Books at the Freer Gallery of Art Library

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2008 Number 146 Article 4 10-1-2008 A Scholar Diplomat's Legacy: William Woodville Rockhill and His Chinese Language Books at the Freer Gallery of Art Library Lily Kecskes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kecskes, Lily (2008) "A Scholar Diplomat's Legacy: William Woodville Rockhill and His Chinese Language Books at the Freer Gallery of Art Library," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2008 : No. 146 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2008/iss146/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 146, October 2008 A SCHOLAR DIPLOMAT‘S LEGACY: WILLIAM WOODVILLE ROCKHILL AND HIS CHINESE LANGUAGE BOOKS AT THE FREER GALLERY OF ART LIBRARY Lily Kecskes The donation of the Chinese library of William Woodville Rockhill (1854-1914) was first mentioned eighty years ago in the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1928, according to which a total of 1,100 volumes from the late scholar diplomat’s library was presented by Mrs. Rockhill, his widow, to the Smithsonian Institution in the autumn of 1927 and was deposited in the Freer Gallery of Art.1 As described in the report, the Rockhill books ranged, in date of publication, from 1659 to 1913 and covered a wide range of subjects, including religion, history, geography, literature, and culture of Central Asia, Tibet and Mongolia. -

Student’S Guide Latin America, Asia, & Africa Second Edition

Lightning Literature & Composition World Literature II: Student’s Guide Latin America, Asia, & Africa Second Edition Acquiring College-Level Composition Skills by Responding to Great Literature The difference between the right word and the almost-right word is the difference between the lightning and the lightning bug.—Mark Twain Brenda S. Cox 2103 Main Street · Washougal, WA 98671 (360) 835-8708 · FAX (360) 835-8697 To my daughter Jasmine, now teaching in China, who helped me discover the joys of World Literature when we studied it together. Cover photo: Sunset view of Torii gate Miyajima, Japan. Copyright Chuong, used under license from Shutterstock.com Edited by Hewitt Staff Mailing address . P. O. Box 9, Washougal WA 98671-0009 For a free catalog . (800) 348-1750 E-mail. [email protected] Website. www.hewitthomeschooling.com ©2007, 2011 by Brenda S. Cox. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of Hewitt Research Foundation Published July 2007. Second Edition January 2012 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 10: 1-57896-262-5 ISBN 13: 978-1-57896-262-4 Table of Contents Introduction . 1 Why Read Literature? . 3 Why Learn How to Write? . 6 Perspectives: The Fluidity of Language and Pronoun Confusion1 . 13 How to Use This Student’s Guide. 15 Activities to Enhance Your Study . 17 Unit 1 Lesson 1: R. K. Narayan (India) (Malgudi Days) (short stories) .