1 UNIT 2 INDIAN SCRIPTURES Contents 2.0 Objectives 2.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kriya-Yoga" in the Youpi-Sutra

ON THE "KRIYA-YOGA" IN THE YOUPI-SUTRA By Shingen TAKAGI The Yogasutra (YS.) defines that yoga is suppression of the activity of mind in its beginning. The Yogabhasya (YBh.) by Vyasa, the oldest (1) commentary on this sutra says "yoga is concentration (samadhi)". Now- here in the sutra itself yoga is not used as a synonym of samadhi. On the other hand, Nyayasutra (NS.) 4, 2, 38 says of "the practice of a spe- cial kind of concentration" in connection with realizing the cognition of truth, and also NS. 4, 2, 42 says that the practice of yoga should be done in a quiet places such as forest, a natural cave, or river side. According NS. 4, 2, 46, the atman can be purified through abstention (yama), obser- vance (niyama), through yoga and the means of internal exercise. It can be surmised that the author of NS. also used the two terms samadhi and yoga as synonyms, since it speaks of a special kind of concentration on one hand, and practice of yoga on the other. In the Nyayabhasya (NBh. ed. NS. 4, 2, 46), the author says that the method of interior exercise should be understood by the Yogasastra, enumerating austerity (tapas), regulation of breath (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), contem- plation (dhyana) and fixed-attention (dharana). He gives the practice of yoga (yogacara) as another method. It seems, through NS. 4, 2, 46 as mentioned above, that Vatsyayana regarded yama, niyama, tapas, prana- yama, pratyahara, dhyana, dharana and yogacara as the eight aids to the yoga. -

Bulletin Journal of Sport Science and Physical Education

International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education Conseil International pour l‘Education Physique et la Science du Sport Weltrat für Sportwissenschaft und Leibes-/Körpererziehung Consejo International para la Ciencia del Deporte y la Educatión Física Bulletin Journal of Sport Science and Physical Education No 71, October 2016 Special Feature: Exercise and Science in Ancient Times freepik.com ICSSPE/CIEPSS Hanns-Braun-Straße 1, 14053 Berlin, Germany, Tel.: +49 30 311 0232 10, Fax: +49 30 311 0232 29 ICSSPE BULLETIN TABLE OF CONTENT 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................... 2 PUBLISHER‘S STATEMENT .................................................................................................. 3 FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................... 4 Editorial Katrin Koenen ...................................................................................................... 4 President‘s Message Uri Schaefer ....................................................................................................... 5 Welcome New Members ................................................................................... 6 SPECIAL FEATURE: Exercise and Science in Ancient Times Introduction Suresh Deshpande .............................................................................................. 8 Aristotelian Science behind Medieval European Martial -

Conversaciones Con Sri Ramana Maharshi (Tomo I)

Comparta este documento si lo desea, pero hágalo siempre de forma GRATUITA. CONVERSACIONES CON Sri Ramana Maharshi (Tomo I) Conversaciones con Sri Ramana Maharshi (Tomo I) PREFACIO Estas «Conversaciones», publicadas originalmente en tres tomos, se presentan ahora en uno solo. No hay dudad de que la presente edición será recibida por los aspirantes del mundo entero con la misma veneración y respeto que la anterior. Éste no es un libro para leerlo a la ligera y dejarlo de lado; está destinado a proporcionar una guía infalible al creciente número de peregrinos que marchan hacia la Luz Sempiterna. Nuestra profunda gratitud hacia Sri Munagala S. Venkataramiah (actualmente, Swami Ramanananda Saraswati) por el registro que ha conservado de las «Conversacio- nes» que abarca un periodo de cuatro años, desde 1935 a 1939. Aquellos devotos que tuvieron la buena fortuna de ver a Bhagaván Sri Ramana, al leer estas «Conversacio- nes», las rememorarán naturalmente, y recordarán con deleite sus propios registros mentales de las palabras del Maestro. A pesar del hecho de que el gran Sabio de Aruna- chala enseñaba la mayor parte del tiempo a través del silencio, instruía también a través del habla, y eso igualmente, con lucidez y sin desconcertar ni confundir las mentes de quienes lo escuchaban. Uno hubiera deseado que todas las palabras que pronunció se hubieran conservado para la posteridad. Pero tenemos que estar agradecidos por las conversaciones que se han registrado. Se encontrará que estas «Conversaciones» arrojan luz sobre los «Escritos» del Maestro y, probablemente, lo mejor sea estudiarlas junto con los «Escritos», cuyas traducciones es posible obtener. -

PDF Format of This Book

COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD SWAMI KRISHNANANDA Published by THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India www.sivanandaonline.org, www.dlshq.org First Edition: 2017 [1,000 copies] ©The Divine Life Trust Society EK 56 PRICE: ` 95/- Published by Swami Padmanabhananda for The Divine Life Society, Shivanandanagar, and printed by him at the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy Press, P.O. Shivanandanagar, Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India For online orders and catalogue visit: www.dlsbooks.org puBLishers’ note We are delighted to bring our new publication ‘Commentary on the Mundaka Upanishad’ by Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj. Saunaka, the great householder, questioned Rishi Angiras. Kasmin Bhagavo vijnaate sarvamidam vijnaatam bhavati iti: O Bhagavan, what is that which being known, all this—the entire phenomena, experienced through the mind and the senses—becomes known or really understood? The Mundaka Upanishad presents an elaborate answer to this important philosophical question, and also to all possible questions implied in the one original essential question. Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave a verse-by-verse commentary on this most significant and sacred Upanishad in August 1989. The insightful analysis of each verse in Sri Swamiji Maharaj’s inimitable style makes the book a precious treasure for all spiritual seekers. —THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY 5 TABLE OF Contents Publisher’s Note . 5 CHAPTER 1: Section 1 . 11 Section 2 . 28 CHAPTER 2: Section 1 . 50 Section 2 . 68 CHAPTER 3: Section 1 . 85 Section 2 . 101 7 COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD Chapter 1 SECTION 1 Brahmā devānām prathamaḥ sambabhūva viśvasya kartā bhuvanasya goptā, sa brahma-vidyāṁ sarva-vidyā-pratiṣṭhām arthavāya jyeṣṭha-putrāya prāha; artharvaṇe yām pravadeta brahmātharvā tām purovācāṅgire brahma-vidyām, sa bhāradvājāya satyavāhāya prāha bhāradvājo’ṇgirase parāvarām (1.1.1-2). -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

The Ultimate Origin of the World, Or the Mula Muh, and Other Mon Beliefs*

THE ULTIMATE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD, OR THE MULA MUH, AND OTHER MON BELIEFS* EMMANUEL GUILLON FORMER CHARGE DE CONFERENCE ECOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ETUDES SECTION DES SCIENCES RELIGEUSES PARIS Can we credit the Mons with possessing a world view, a The first things that came into being were the seasons, hot mental universe, a landscape of feelings and emotions, which and cold. They both appeared at once and were followed by we can deduce from their myths, beliefs and rites, and which a wind that never ceased blowing. The air expanded until it thus is uniquely their own? Since we are by no means deal became an enormous mass. Then the water appeared and ex ing with a human isolate (if indeed such a thing has ever panded also. A mist began to rise up from the water and existed), we will inevitably encounter a network of foreign then fell as rain. The dry season evaporated the water and influences. But such influences often are modified by the the land appeared. The land was able to produce stones and genius of a language and a people. Does there still survive, minerals, and silver, gold, iron, tin and copper soon appeared then, some explanation of the world that can be considered as well as the various precious stones. Then the first kinds of uniquely characteristic of the Mons? vegetation appeared on the gold ore as a kind of moss, fol lowed by grass and all the other plants of the vegetable Mula Muh kingdom. There,does exist, in fact, a cosmology of which we have "The four elements had the propensity to produce living beings. -

THE UNIVERSITY of CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Jackson College of Graduate Studies

THE UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Jackson College of Graduate Studies The Effects of Samatva Yoga on Perceived Stress among University Students in the Midwest A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF SCIENCE By Avy M. Doran Edmond, Oklahoma 2011 COPYRIGHT By Avy M. Doran December 2011 ii Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. C. Diane Rudebock, Dr. Melissa Powers, and Dr. Jill Devenport for all their guidance, insightfulness, and time. Having the help of a knowledgeable and forthright thesis committee made the thesis process run smoothly. I also want to thank the Department of Kinesiology and Health Studies at the University of Central Oklahoma. Without the assistance of several department faculty and staff, it would have been more difficult to accomplish my goals in such a short time. Your efforts are truly appreciated! iv Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of Samatva yoga on perceived stress among university students in the Midwest. Criteria for participants included that participants were students at a University located in a metropolitan area and enrolled in two sections of the 2011 fall yoga courses. The comparison group included participants from the two different universities enrolled in a fall 2011 weight training courses. Weight training was chosen as the comparison group because it was the most closely related form of exercise to yoga. Demographic data were collected on participants before the questionnaires were administered. The questionnaires, Perceived Stress Scales (PSS) and Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) instruments which measure stress and optimism were administered as a pre-test to university students enrolled in yoga and weight training for the fall 2011 semester. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

The Lotus Sutra: Opening the Way for the Enlightenment of All People

The Lotus Sutra: Opening the Way for the Enlightenment of All People he Great Teacher T’ien-t’ai of China disciples known as voice-hearers and cause- analyzed the content and meaning of awakened ones), women and evil persons from all the Buddhist sutras, concluding the possibility of ever becoming Buddhas. And Tthat the Lotus Sutra constitutes the highest even for those considered capable of attaining essence of Buddhist teachings. Buddhahood, the pre-Lotus Sutra teachings He classified the Lotus Sutra as conveying presume that the process of doing so requires the teachings that Shakyamuni Buddha countless lifetimes of austere practice. There expounded toward the end of his life, which is no recognition that an ordinary person can the Buddha intended to be passed on to the attain Buddhahood in this single lifetime. The future for the enlightenment of all people. Lotus Sutra, on the other hand, makes clear T’ien-t’ai also pointed out that teachings the that all people without exception possess a Buddha expounded prior to the Lotus Sutra Buddha nature and indicates that they can should be regarded as “expedient means” attain enlightenment in this life, as they are, and set aside. In the Immeasurable Meanings in their present form. Sutra, considered an introduction to the Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni says: “Preaching the Law in various different ways, I made use of the Outline and Structure of power of expedient means. But in these more the Lotus Sutra than forty years, I have not yet revealed the truth” (The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and n analyzing the contents of the Lotus Sutra, Closing Sutras, p. -

Hinduism and Social Work

5 Hinduism and Social Work *Manju Kumar Introduction Hinduism, one of the oldest living religions, with a history stretching from around the second millennium B.C. to the present, is India’s indigenous religious and cultural system. It encompasses a broad spectrum of philosophies ranging from pluralistic theism to absolute monism. Hinduism is not a homogeneous, organized system. It has no founder and no single code of beliefs; it has no central headquarters; it never had any religious organisation that wielded temporal power over its followers. Hinduism does not have a single scripture as the source of its various teachings. It is diverse; no single doctrine (or set of beliefs) can represent its numerous traditions. Nonetheless, the various schools share several basic concepts, which help us to understand how most Hindus see and respond to the world. Ekam Satya Viprah Bahuda Vadanti — “Truth is one; people call it by many names” (Rigveda I 164.46). From fetishism, through polytheism and pantheism to the highest and the noblest concept of Deity and Man in Hinduism the whole gamut of human thought and belief is to be found. Hindu religious life might take the form of devotion to God or gods, the duties of family life, or concentrated meditation. Given all this diversity, it is important to take care when generalizing about “Hinduism” or “Hindu beliefs.” For every class of * Ms. Manju Kumar, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, Delhi University, Delhi. 140 Origin and Development of Social Work in India worshiper and thinker Hinduism makes a provision; herein lies also its great power of assimilation and absorption of schools of philosophy and communities of people, (Theosophy, 1931). -

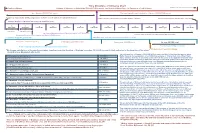

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture.