Hedge Funds and Systemic Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Financial Services Industry Outlook

NEW YORK 535 Madison Avenue, 19th Floor New York, NY 10022 +1 212 207 1000 SAN FRANCISCO One Market Street, Spear Tower, Suite 3600 San Francisco, CA 94105 +1 415 293 8426 DENVER 999 Eighteenth Street, Suite 3000 2017 Denver, CO 80202 FINANCIAL SERVICES +1 303 893 2899 INDUSTRY REVIEW MEMBER, FINRA / SIPC SYDNEY Level 2, 9 Castlereagh Street Sydney, NSW, 2000 +61 419 460 509 BERKSHIRE CAPITAL SECURITIES LLC (ARBN 146 206 859) IS A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY INCORPORATED IN THE UNITED STATES AND REGISTERED AS A FOREIGN COMPANY IN AUSTRALIA UNDER THE CORPORATIONS ACT 2001. BERKSHIRE CAPITAL IS EXEMPT FROM THE REQUIREMENTS TO HOLD AN AUSTRALIAN FINANCIAL SERVICES LICENCE UNDER THE AUSTRALIAN CORPORATIONS ACT IN RESPECT OF THE FINANCIAL SERVICES IT PROVIDES. BERKSHIRE CAPITAL IS REGULATED BY THE SEC UNDER US LAWS, WHICH DIFFER FROM AUSTRALIAN LAWS. LONDON 11 Haymarket, 2nd Floor London, SW1Y 4BP United Kingdom +44 20 7828 2828 BERKSHIRE CAPITAL SECURITIES LIMITED IS AUTHORISED AND REGULATED BY THE FINANCIAL CONDUCT AUTHORITY (REGISTRATION NUMBER 188637). www.berkcap.com CONTENTS ABOUT BERKSHIRE CAPITAL Summary 1 Berkshire Capital is an independent employee-owned investment bank specializing in M&A in the financial services sector. With more completed transactions in this space than any Traditional Investment Management 6 other investment bank, we help clients find successful, long-lasting partnerships. Wealth Management 9 Founded in 1983, Berkshire Capital is headquartered in New York with partners located in Cross Border 13 London, Sydney, San Francisco, Denver and Philadelphia. Our partners have been with the firm an average of 14 years. We are recognized as a leading expert in the asset management, Real Estate 17 wealth management, alternatives, real estate and broker/dealer industries. -

Alternative Investment Fund in the USA

May 2016 globalfund www.globalfundmedia.commediaspecial report 2016 Guide to setting up an Alternative Investment Fund in the USA CoverlineStructuring 1 a GradingCoverline your 2 cloud HowCoverline to assess 3 tax‑efficient provider: critical a prime broker’s hedge fund criteria operational support Forward thinking is the fi rst step We’re committed to providing smart, clear and honest guidance to help you meet your goals. From hedge funds and fund of funds to private equity, we are experienced with virtually every type of product in the market. Trust that our global alternative investment experts can provide innovative solutions to help support your plans for success. Global hedge fund administration made simple Administration and accounting Middle offi ce services Custody services Registered offi ce services Investor services Tax services Legal administration Technology and compliance Treasury services For more information about our comprehensive suite of services for alternative funds, exchange-traded funds and mutual funds, call 800.300.3863 or visit usbfs.com. CONTENTS In this issue… 04 Introduction By Sunil Gopalan, Chairman & Publisher, GFM Ltd 05 Chapter 1: Legal & tax structuring 08 Structuring a tax-efficient hedge fund Interview with Ron Geffner, Sadis & Goldberg LLP 11 Grading your cloud provider: four critical criteria By Bob Guilbert, Eze Castle Integration 13 Chapter 2: Regulations & compliance 16 Compliance mindset to be set by senior management Interview with Brian Roberts, ACA Compliance Group 19 ODD considerations for -

Geographic Diversification Can Be a Lifesaver, Yet Most Portfolios Are Highly Geographically Concentrated

Geographic Diversification Can Be a Lifesaver, Yet Most Portfolios Are Highly Geographically Concentrated FEBRUARY 2019 MELISSA SAPHIER KAREN KARNIOL-TAMBOUR PAT MARGOLIS © 2019 Bridgewater Associates, LP he best way we know to earn consistent returns and preserve wealth is to build portfolios that are as resilient as possible to the range of ways the Tworld could unfold. To uncover vulnerabilities that are outside of investors’ recent lived experiences, we find it valuable to stress test portfolios across the various environments that have cropped up across countries throughout history. One common vulnerability is geographic concentration. dominant economic force and keeper of a stable global In the past century, there have been many times when geopolitical order. Looking ahead, China’s ascent as an investors concentrated in one country saw their wealth independent economic and financial center of gravity wiped out by geopolitical upheavals, debt crises, monetary with an independent monetary policy and credit system reforms, or the bursting of bubbles, while markets in is highly diversifying, making the world less unipolar other countries remained resilient. Even without such and less correlated. At the same time, the rising risk of extreme events, there is always a big divergence across conflict within and across countries also increases the the best and worst performing countries in any given chances of divergent outcomes. Additionally, geographic period. And no one country consistently outperforms, as diversification felt less urgent during the recent decade outperformance can lead to relative overvaluation and a of great returns for most assets and portfolios. Low asset subsequent reversal. Rather than try to predict who the yields going forward make diversification and efficient winner will be in any particular period, a geographically risk-taking all the more important to investors. -

Dynamic Strategic Arbitrage∗

Dynamic Strategic Arbitrage∗ Vincent Fardeauy Frankfurt School of Finance and Managment This version: June 11, 2014 Abstract Asset prices do not adjust instantaneously following uninformative demand or supply shocks. This paper offers a theory based on arbitrageurs' price impact to explain these slow-moving cap- ital dynamics. Arbitrageurs recognizing their price impact break up trades, leading to gradual price adjustments. When shocks are anticipated, prices exhibit a V-shaped pattern, with a peak at the realization of the shocks. The dynamics of market depth and price adjustments depend on the degree of competition between arbitrageurs. When shocks are uncertain, price dynamics depend on the interaction between arbitrageurs' competition and the total risk-bearing capacity of the market. JEL codes: G12, G20, L12; Keywords: Strategic arbitrage, liquidity, price impact, limits of arbitrage. ∗I benefited from comments from Miguel Ant´on,Bruno Biais, Maria-Cecilia Bustamante, Amil Dasgupta, Michael Gordy, Martin Oehmke (discussant), Matt Pritsker, Jean-Charles Rochet, Yuki Sato, Kostas Zachariadis, Jean-Pierre Zigrand and seminar and conference participants at LSE, INSEAD, FRB, the University of Zurich and the 2013 AFA meetings in San Diego. I am grateful to Dimitri Vayanos and Denis Gromb for supervision and insights. Jay Im provided excellent research assistance. This paper is the first part of a paper previously circulated as \Strategic Arbitrage with Entry". All remaining errors are my own. yDepartment of Finance, Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, Sonnemannstrasse 9-11, 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Email: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction Empirical evidence shows that prices recover slowly from demand or supply shocks that are unre- lated to future earnings and that these patterns are due to imperfections in the supply of capital. -

Carlson Order Denying Motion for Subpoena

BEFORE THE NATIONAL ADJUDICATORY COUNCIL NASD ____________________________________ : In the Matter of : : Department of Enforcement, : DECISION : Complainant, : Complaint No. CAF980002 : vs. : : John Fiero : Dated: October 28, 2002 Jersey City, NJ : : : and : : : Pembroke Pines, FL : : and : : Fiero Brothers, Inc. : New York, NY, : : : Respondents : : ____________________________________: Firm and its president appeal findings that they, in cooperation with others, manipulated the market for certain securities and engaged in coercive conduct; and that they violated NASD's affirmative determination rule. Held, findings affirmed and sanctions of bar, expulsion, and fine upheld. Appearances For the Complainant Department of Enforcement: Robert L. Furst, Esq. and Jonathan I. Golomb, NASD Department of Enforcement. For the Respondents John Fiero and Fiero Brothers, Inc.: Martin H. Kaplan and Brian D. Graifman, Gusrae, Kaplan & Bruno; Martin P. Russo, MPR Law Practice, P.C.; Lewis D. Lowenfels, Tolins & Lowenfels. - 2 - Opinion John Fiero ("Fiero") and Fiero Brothers, Inc. ("Fiero Brothers" or "the Firm") (collectively, the "Fiero Respondents") appeal a December 6, 2000 decision of an NASD Hearing Panel. The Hearing Panel held that the Fiero Respondents, in cooperation with others and through the use of collusive trading activity, manipulated the market for certain securities, in violation of Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ("Exchange Act"), Exchange Act Rule 10b-5, and Conduct Rules 2110 and 2120 and effected short sales of securities without making the affirmative determinations required by Conduct Rule 3370, in violation of Rules 2110 and 3370. In summary, the Hearing Panel found that the manipulation violation involved the Fiero Respondents' colluding with other short sellers to drive down the prices of several small-cap securities. -

Starting a Hedge Fund in the Sophomore Year

FEATURING:FEATURING:THETHE FALL 2001 COUNTRY CREDIT RATINGSANDTHE WORLD’S BEST HOTELS SEPTEMBER 2001 BANKING ON DICK KOVACEVICH THE HARD FALL OF HOTCHKIS & WILEY MAKING SENSE OF THE ECB PLUS: IMF/WorldBank Special Report THE EDUCATION OF HORST KÖHLER CAVALLO’S BRINKMANSHIP CAN TOLEDO REVIVE PERU? THE RESURGENCE OF BRAZIL’S LEFT INCLUDING: MeetMeet The e-finance quarterly with: CAN CONSIDINE TAKE DTCC GLOBAL? WILLTHE RACE KenGriffinKenGriffin GOTO SWIFT? Just 32, he wants to run the world’s biggest and best hedge fund. He’s nearly there. COVER STORY en Griffin was desperate for a satellite dish, but unlike most 18-year-olds, he wasn’t looking to get an unlimited selection of TV channels. It was the fall of 1987, and the Harvard College sophomore urgently needed up-to-the-minute stock quotes. Why? Along with studying economics, he hap- pened to be running an investment fund out of his third-floor dorm room in the ivy-covered turn- of-the-century Cabot House. KTherein lay a problem. Harvard forbids students from operating their own businesses on campus. “There were issues,” recalls Julian Chang, former senior tutor of Cabot. But Griffin lobbied, and Cabot House decided that the month he turns 33. fund, a Florida partnership, was an off-campus activity. So Griffin’s interest in the market dates to 1986, when a negative Griffin put up his dish. “It was on the third floor, hanging out- Forbes magazine story on Home Shopping Network, the mass side his window,” says Chang. seller of inexpensive baubles, piqued his interest and inspired him Griffin got the feed just in time. -

Can Policy Makers Actually Get What They Want?

Can Policy Makers Actually Get What They Want? MAY 28, 2020 GREG JENSEN JASON ROGERS © 2020 Bridgewater Associates, LP he pandemic and the shutdowns that followed have opened two distinct but related holes—a hole in incomes (the real economy), and Ta hole in asset markets. If left unfilled, these holes would produce a self-reinforcing collapse and intolerable economic and social outcomes. The longer they persist, the greater the accumulated problems and the higher the likelihood of prolonged economic weakness as households and businesses sell assets and eat through cash balances until more and more entities are bankrupt. Faced with this, the main policy choice is whose balance sheets will bear the losses, which will determine to some extent how the economy rebounds after the health emergency eases. Many policy makers are now attempting to use government balance sheets to fill these two holes through coordinated monetary and fiscal policy (MP3)—filling the gap in markets with the central bank balance sheet through QE, and filling the gap in incomes with the government balance sheet through fiscal stimulus monetized by that QE. The intent is to avoid a collapse in markets and to bridge the gap in incomes so that when the pandemic is over companies are still intact, workers can get back to work, and the economy can quickly get back on its feet. In other words, policy makers hope to reduce the impact of the pandemic to a short- term interruption in activity and avoid long-term economic problems. While this approach makes sense to us, it is far from assured that policy makers will be able to get what they want. -

International Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading Summit

TH NovemberTH & 15 14 Mexico City WWW.RISKMATHICS.COM …” Two DAY SUMMIT WITH THE MOST ACKNOWLEDGED AUTHORITIES AND THE BIG PLAYERS IN THE TRADING INDUSTRY WORLD-WIDE” DAVID LEINWEBER GEORGE KLEDARAS MARCOS M. LÓPEZ DE MARCO AVELLANEDA DAN ROSEN YOUNG KANG JORGE NEVID Center for Innovative Founder & Chairman PRADO Courant Institute CEO Global Head of Sales & Electronic Trading Financial Technology FixFlyer Head of Global of Mathematical R2 Financial Algorithmic Products Acciones y Valores Lawrence Berkeley Lab Quantitative Research Sciences, NYU and Technologies Citigroup Banamex Tudor Investment Corp. Senior Partner, Finance Concepts LLC SEBASTIÁN REY CARLOS RAMÍREZ JOHN HULL KARLA SILLER VASSILIS VERGOTIS SANDY FRUCHER JULIO BEATON Electronic Trading Banorte - IXE Toronto University National Banking and Executive Vice President Vice Chairman TradeStation GBM Casa de Bolsa Securities Commission European Exchange NASDAQ OMX Casa de Bolsa CNBV (Eurex) RiskMathics, aware that the most important factor to develop and consolidate the financial markets is training and promoting a high level financial culture, will host: “Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading Summit”, which will have the participation of leading market practitioners who have key roles in the financial industry locally and internationally. Currently the use of Automated/Black-Box trading in combination with the extreme speed in which orders are sent and executed (High Frequency Trading) are without a doubt the most important trends in the financial industry world-wide. The possibility to have direct access to the markets and to send burst orders in milliseconds, has been a fundamental factor in the exponential growth in the number of transactions that we have seen in recent years. -

Oundtable Reenwich

The Education Committee of reenwichThe oundtable G Knowledge,R Veracity, Fellowship 2010 In This Issue The Art of Asking Questions Best Practices in Hedge Fund Strategies Alternative Investments: DUE DILIGENCE Private Illiquid Strategies The Final Analysis The Greenwich Roundtable One River Road Cos Cob, Connecticut 06807 Tel.: 203-625-2600 Fax: 203-625-4523 www.greenwichroundtable.org Best Practices in alternative investments: www.greenwichroundtaBle.org due diligence Research About the Greenwich Education Council Roundtable Committee Tudor Investment Corporation The Greenwich Roundtable, Inc., is a not-for- BEST PRACTICE MEMBERS Blenheim Capital Management profit research and educational organization located in Greenwich, Connecticut, for investors Robert M. Aaron Bridgewater Associates, Inc. who allocate capital to alternative investments. Gilwern Investments, LLC It is operated in the spirit of an intellectual BlackRock, Inc. cooperative for the alternative investment Benjamin Alimansky Moore Capital Management community. Its 150 members are comprised of Glenmede Trust mostly institutional and private investors, who The Lumina Foundation collectively control $4.5 trillion in assets. Edgar W. Barksdale Federal Street Partners The purpose of the Greenwich Roundtable is to discuss and provide current, cutting-edge Ray Gustin IV information on non-traditional investing. Our Drake Capital Advisors, LLC mission is to reveal the essence of both trusted and new investing styles and to create a code of Damian Handzy best practices for the alternative investor. Investor Analytics Brijesh Jeevarathnam Commonfund Capital, Inc. Jennifer Keeney Tatanka Asset Management, LLC The Research Council enables the Jeffrey P. Kelly Greenwich Roundtable to host Summit Rock Advisors the broadest range of investigation that serves the interests of the Russell L. -

02. February.Pmd

MBA Education & Careers Eco Fundas for you Stock Market Dealers BEAR BULL bear is a dealer on a stock exchange, dealer on a stock exchange, currency A currency or commodity market, who A or commodity market, who expects expects prices to fall. prices to rise is called a bull. A bear market is one in which a dealer is A bull market is one in which a dealer is more likely to sell securities, currency or more likely to be a buyer than a seller, even goods without having them. This is known to the extent of buying for his or her own as selling short or establishing a bear account and establishing a bull position. position. The bear hopes to close (or cover) such a short position by buying in at a lower A bull with a long position hopes to sell the price the securities, currency or goods purchases at a higher price after the market already sold. The difference between the has risen. A bull position or long position purchase price and the original sale price occurs when the bull owns securities. represents the successful bear’s profit. JOBBER A concerted attempt to force prices down by jobber is an independent dealer in a powerful bear (or a group of them) by A securities. He purchases and sells resorting to sustained selling is called a securities in his own name. He is not allowed bear raid. to deal with non-members directly. 34 February 2012 MBA Education & Careers ECO FUNDAS FOR YOU Stock Market Dealers CHICKEN PIG hickens are afraid to lose anything. -

Optimal Convergence Trading with Unobservable Pricing Errors

OPTIMAL CONVERGENCE TRADING WITH UNOBSERVABLE PRICING ERRORS SÜHAN ALTAY, KATIA COLANERI, AND ZEHRA EKSI Abstract. We study a dynamic portfolio optimization problem related to convergence trading, which is an investment strategy that exploits temporary mispricing by simultane- ously buying relatively underpriced assets and selling short relatively overpriced ones with the expectation that their prices converge in the future. We build on the model of Liu and Timmermann [22] and extend it by incorporating unobservable Markov-modulated pricing errors into the price dynamics of two co-integrated assets. We characterize the optimal portfolio strategies in full and partial information settings both under the assumption of unrestricted and beta-neutral strategies. By using the innovations approach, we provide the filtering equation that is essential for solving the optimization problem under partial information. Finally, in order to illustrate the model capabilities, we provide an example with a two-state Markov chain. 1. Introduction Convergence-type trading strategies have become one of the most popular trading strate- gies that are used to capitalize on market inefficiencies, or deviations from “equilibrium,” especially with the rapid developments in algorithmic and high-frequency trading. For a typical convergence trade, temporary mispricing is exploited by simultaneously buying rel- atively underpriced assets and selling short relatively overpriced assets in anticipation that at some future date their prices will have become closer. Thus one can profit by the extent of the convergence. A prime example of a convergence trade is a pairs trading strategy that involves a long position and a short position in a pair of similar stocks that have moved together historically and hence an investor can profit from the relative value trade arising arXiv:1910.01438v2 [q-fin.PM] 7 Oct 2019 from the cointegration between asset price dynamics involved in the trade. -

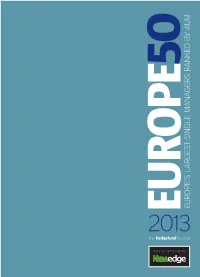

Europe's Largest Single Managers Ranked by a Um

2013 IN ASSOCIATION WITH IN ASSOCIATION 5O EUROPEEUROPE’S LARGEST SINGLE MANAGERS RANKED BY AUM EUROPE50 01 02 03 04 Brevan Howard Man BlueCrest Capital Blackrock Management 1 1 1 1 Total AUM (as at 30.06.13) Total AUM (as at 30.06.13) Total AUM (as at 01.04.13) Total AUM (as at 30.06.13) $40.0bn $35.6bn $34.22bn $28.7bn 2 2 2 2 2012 ranking 2012 ranking 2012 ranking 2012 ranking 2 1 3 6 3 3 3 3 Founded Founded Founded Founded 2002 1783 (as a cooperage) 2000 1988 4 4 4 4 Founders/principals Founders/principals Founders/principals Founders/principals Alan Howard Manny Roman (CEO), Luke Ellis (President), Mike Platt, Leda Braga Larry Fink Jonathan Sorrell (CFO) 5 5 5 Hedge fund(s) 5 Hedge fund(s) Hedge fund(s) Fund name: Brevan Howard Master Fund Hedge fund(s) Fund name: BlueCrest Capital International Fund name: UK Emerging Companies Hedge Limited Fund name: Man AHL Diversified plc Inception date: 12/2000 Fund Inception date: 04/2003 Inception date:03/1996 AUM: $13.5bn Inception date: Not disclosed AUM: $27.4bn AUM: $7.9bn Portfolio manager: Mike Platt AUM: Not disclosed Portfolio manager: Multiple portfolio Portfolio manager: Tim Wong, Matthew Strategy: Global macro Portfolio manager: Not disclosed managers Sargaison Asset classes: Not disclosed Strategy: Equity long/short Strategy: Global macro, relative value Strategy: Managed futures Domicile: Not disclosed Asset classes: Not disclosed Asset classes: Fixed income and FX Asset classes: Cross asset Domicile: Not disclosed Domicile: Cayman Islands Domicile: Ireland Fund name: BlueTrend