Download a PDF of Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joséphine Magnard Tim Burton's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Joséphine Magnard Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Fairy Tale between Tradition and Subversion ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MAGNARD Joséphine. Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Fairy Tale between Tradition and Subversion, sous la direction de Mehdi Achouche. - Lyon : Université Jean Moulin (Lyon 3), 2018. Mémoire soutenu le 18/06/2019. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Document diffusé sous le contrat Creative Commons « Paternité – pas d’utilisation commerciale - pas de modification » : vous êtes libre de le reproduire, de le distribuer et de le communiquer au public à condition d’en mentionner le nom de l’auteur et de ne pas le modifier, le transformer, l’adapter ni l’utiliser à des fins commerciales. Master 2 Recherche Etudes Anglophones Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Fairy Tale between Tradition and Subversion A dissertation presented by Joséphine Magnard Year 2017-2018 Under the supervision of Mehdi Achouche, Senior Lecturer ABSTRACT The aim of this Master’s dissertation is to study to what extent Tim Burton plays with the codes of the fairy tale genre in his adaptation of Roald Dahl’s children’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964). To that purpose, the characteristics of the fairy tale genre will be treated with a specific focus on morality. The analysis of specific themes that are part and parcel of the genre such as childhood, family and home will show that Tim Burton’s take on the tale challenges the fairy tale codes, providing its viewers with a more Tim Burtonesque, subversive approach where things are not as definable as they might seem. -

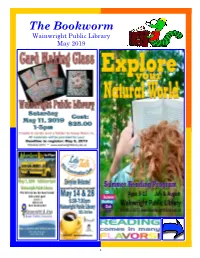

The Bookworm Wainwright Public Library May 2019

The Bookworm Wainwright Public Library May 2019 1 Adult Fiction Baby-Led Weaning: The Essential Guide to Introducing Solid Rush by Maya Banks Foods & Helping Your Baby to Grow Up a Happy and Fat Tuesday by Sandra Brown Confident Eater by Gill Rapley The Forgiving Jar by Wanda E. Brunstetter The Trident: The Forging and Reforging of a Navy Seal Leader The Hope Jar by Wanda E. Brunstetter by Jason Redman Thirteen by Steve Cavanagh Numerology: Your Character and Future Revealed in Numbers Brother by David Chariandy by Norman Shine The Unexpected Champion by Mary Connealy Feng Shui Step by Step: Arranging Your Home for Health and Believe Me by J. P. Delaney Happiness by T. Raphael Simons Code of Valor by Lynette Eason Just for Today: Daily Meditations for Recovering Addicts Mending Fences by Suzanne Woods Fisher Large Print A Faithful Gathering by Leslie Gould The Last Romantics by Tara Conklin Song of a Nation by Robert Harris The Wedding Guest by Jonathan Kellerman Before the Fall by Noah Hawley To the Moon and Back by Karen Kingsbury That Perfect Someone by Johanna Lindsey Devil’s Daughter by Lisa Kleypas The Best of Intentions by Susan Anne Mason The Huntress by Kate Quinn Texas Ranger by James Patterson Daisy Jones & the Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid Out of the Ashes by Tracie Peterson Careless Love: a DCI Banks novel by Peter Robinson Under the Midnight Sun by Tracie Peterson Audio Book When You Are Near by Tracie Peterson The Survivor by Vince Flynn At the Wolf’s Table by Rosella Postorino Blu-Ray Shameless by Karen Robards Aquaman WPL will be The Sky Above Us by Sarah Sudin Bumblebee A Certain Age by Beatriz Williams A Dog’s Way Home closed on Hearts in Harmony by Beth Wiseman Holmes & Watson Monday, May 20th Adult Non-Fiction Mary Poppins Returns for the long weekend. -

Deconstructing Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory: Race, Labor

Chryl Corbin Deconstructing the Oompa-Loompas Deconstructing Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory: Race, Labor, and the Changing Depictions of the Oompa-Loompas Chryl Corbin Mentor: Leigh Raiford, Ph.D. Department of African American Studies Abstract In his 1964 book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Roald Dahl de- picts the iconic Oompa-Loompas as A!ican Pygmy people. Yet, in 1971 Mel Stuart’s "lm Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory the Oompa- Loompas are portrayed as little people with orange skin and green hair. In Dahl’s 1973 revision of this text he depicts the Oompa-Loompas as white. Finally, in the "lm Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005) Tim Burton portrays the Oompa-Loompas as little brown skin people. #is research traces the changing depictions of the Oompa-Loompas throughout the written and "lm text of the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory narra- tive while questioning the power dynamics between Willy Wonka and the Oompa-Loompas characters. #is study mo$es beyond a traditional "lm analysis by comparing and cross analyzing the narratives !om the "lms to the original written texts and places them within their political and his- torical context. What is revealed is that the political and historical context in which these texts were produced not only a%ects the narrative but also the visual depictions of the Oompa-Loompas. !e Berkeley McNair Research Journal 47 Chryl Corbin Deconstructing the Oompa-Loompas Introduction In 1964 British author, Roald Dahl, published the !rst Charlie and the Chocolate Factory book in which the Oompa-Loompas are depicted as black Pygmy people from Africa. -

Teen Titans Von George Pérez Bruderschaft Des Bösen

™ MARV WOLFMAN GEORGE BRUDERSCHAFT PÉREZ ROMEO DES BÖSEN TANGHAL TEEN TITANS VON GEORGE PÉREZ BRUDERSCHAFT DES BÖSEN TEEN TITANS VON GEORGE PÉREZ BRUDERSCHAFT DES BÖSEN Geschrieben von MARV WOLFMAN Gezeichnet von GEORGE PÉREZ und ROMEO TANGHAL Farben von ADRIENNE ROY Original-Cover von GEORGE PÉREZ Übersetzung von JÖRG FASSBENDER Lettering von ASTARTE DESIGN Batman geschaffen von Bob Kane mit Bill Finger. Alle Storys von MARV WOLFMAN, 36 alle Cover und Zeichnungen von ENTFESSELTES PROMETHIUM! GEORGE PÉREZ und Tusche von Promethium Unbound! ROMEO TANGHAL, wenn nicht The New Teen Titans 10 anders vermerkt. August 1981 62 6 TREFFEN DER TITANEN! Vorwort When Titans Clash! von Marv Wolfman The New Teen Titans 11 September 1981 10 WIE MARIONETTEN! 88 Like Puppets on a String! SCHLACHT DER TITANEN! The New Teen Titans 9 Clash of the Titans! Juli 1981 The New Teen Titans 12 Oktober 1981 Tusche von FRANK CHIARAMONTE 116 173 FREUND UND FEIND! DIE BRUDERSCHAFT DES Friends and Foes Alike! BÖSEN KEHRT ZURÜCK! The New Teen Titans 13 The Brotherhood of Evil Lives Again! November 1981 The New Teen Titans 15 Tusche auf Cover von Januar 1982 ROMEO TANGHAL Tusche auf Cover von ROMEO TANGHAL 144 REVOLUTION! 202 Revolution! STARFIRE ENTFESSELT! The New Teen Titans 14 Starfire Unleashed! Dezember 1981 The New Teen Titans 16 Tusche auf Cover von Februar 1982 DICK GIORDANO Tusche auf Cover von ROMEO TANGHAL TEEN TITANS VON GEORGE PÉREZ: BRUDERSCHAFT DES BÖSEN erscheint bei PANINI COMICS, Schloßstraße 76, D-70176 Stuttgart. Geschäftsführer Hermann Paul, Publishing -

The Search for the "Manchurian Candidate" the Cia and Mind Control

THE SEARCH FOR THE "MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE" THE CIA AND MIND CONTROL John Marks Allen Lane Allen Lane Penguin Books Ltd 17 Grosvenor Gardens London SW1 OBD First published in the U.S.A. by Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., and simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd, 1979 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 1979 Copyright <£> John Marks, 1979 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner ISBN 07139 12790 jj Printed in Great Britain by f Thomson Litho Ltd, East Kilbride, Scotland J For Barbara and Daniel AUTHOR'S NOTE This book has grown out of the 16,000 pages of documents that the CIA released to me under the Freedom of Information Act. Without these documents, the best investigative reporting in the world could not have produced a book, and the secrets of CIA mind-control work would have remained buried forever, as the men who knew them had always intended. From the documentary base, I was able to expand my knowledge through interviews and readings in the behavioral sciences. Neverthe- less, the final result is not the whole story of the CIA's attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent. I have done the best I can to make the book as accurate as possible, but I have been hampered by the refusal of most of the principal characters to be interviewed and by the CIA's destruction in 1973 of many of the key docu- ments. -

Prodigal Genius BIOGRAPHY of NIKOLA TESLA 1994 Brotherhood of Life, Inc., 110 Dartmouth, SE, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106 USA

Prodigal Genius BIOGRAPHY OF NIKOLA TESLA 1994 Brotherhood of Life, Inc., 110 Dartmouth, SE, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106 USA "SPECTACULAR" is a mild word for describing the strange experiment with life that comprises the story of Nikola Tesla, and "amazing" fails to do adequate justice to the results that burst from his experiences like an exploding rocket. It is the story of the dazzling scintillations of a superman who created a new world; it is a story that condemns woman as an anchor of the flesh which retards the development of man and limits his accomplishment--and, paradoxically, proves that even the most successful life, if it does not include a woman, is a dismal failure. Even the gods of old, in the wildest imaginings of their worshipers, never undertook such gigantic tasks of world- wide dimension as those which Tesla attempted and accomplished. On the basis of his hopes, his dreams, and his achievements he rated the status of the Olympian gods, and the Greeks would have so enshrined him. Little is the wonder that so-called practical men, with their noses stuck in profit-and-loss statements, did not understand him and thought him strange. The light of human progress is not a dim glow that gradually becomes more luminous with time. The panorama of human evolution is illumined by sudden bursts of dazzling brilliance in intellectual accomplishments that throw their beams far ahead to give us a glimpse of the distant future, that we may more correctly guide our wavering steps today. Tesla, by virtue of the amazing discoveries and inventions which he showered on the world, becomes one of the most resplendent flashes that has ever brightened the scroll of human advancement. -

Concert Introductions

CINEMA IN THE PARK DOLLAR BANK CINEMA IN THE PARK Schenley Park, Flagstaff Hill Sundays and Wednesdays, June 8 – August 31 dusk June 8 ......................................................... Here Comes the Boom (PG) June 11 ....................................................... Man of Steel (PG-13) June 15 ........................................................ The Little Mermaid (G) June 18 ........................................................ Iron Man 3 (PG-13) June 22 ....................................................... Monsters University (G) June 25 ........................................................ Gravity (PG-13) June 29 ........................................................ E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (PG) July 2 ........................................................... Last Vegas (PG-13) July 6 ........................................................... Space Jam (PG) July 9 ........................................................... Thor: The Dark World (PG-13) July 13 ........................................................ Despicable Me 2 (PG) July 16 ......................................................... Saving Mr. Banks (PG-13) July 20 ........................................................ Mary Poppins (not rated) July 23 ......................................................... The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (PG-13) July 27 ......................................................... Big Miracle (PG) July 30 ......................................................... 42 (PG-13) August 3...................................................... -

DROPPING out of SCHOOL – a Systematic and Integrative Research Review on Risk Factors an Interventions Björn Johansson

RAPPORT DROPPING OUT OF SCHOOL – a systematic and integrative research review on risk factors an interventions Björn Johansson Working Papers and Reports Social work 16 I ÖREBRO 2019 Editors: Björn Johansson and Daniel Uhnoo TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................... 5 Aim............................................................................................................... 7 Method and search procedures .......................................................................... 7 Search strategy .............................................................................................. 7 Data Extraction ............................................................................................ 10 The analytical framework ................................................................................ 10 The characteristics of at-risk students and dropouts ............................................. 11 Risk and protective factors for dropout .............................................................. 14 Risk and protective factors at the individual level ................................................ 15 Risk and protective factors at the interpersonal level ........................................... 20 Risk and protective factors at the organisational level .......................................... 23 Risk and protective factors at the societal level .................................................. 24 Concluding remarks ...................................................................................... -

Tarzan (Na- “It’S Liketellingsomeone Who Crystal Cale, WHS Psychology One Infour American Teenagers “‘Smile, You’Llfeelbetter

Sports - Pages15-18 Prom - Pages 11-14 Feature -Pages 7-10 Editorial- Page 6 News -Pages1-5 wear anypants. he doesn’t because Finland from banned ics were Duck com- Donald In thecourseofanaver- Sunday willalwayshave PRSRT STD assorted insectsand10 Inside This apples, waspslikepine age lifetime,youwill, while sleeping,eat70 Months thatbeginona nuts, andwormslike Sweet Dreams U.S. Postage Paid a “Fridaythe13th.” Lucky Months Disney Dress Beetles tastelike That Really Ogden, UT Odds New Food Ends fried bacon. Issue Permit No. 208 Group spiders. Code Bugs! ‘n’ A cockroachcan A live several WEBER HIGHSCHOOL430WESTDRIVEPLEASANTVIEW,UT84414W head cut with its weeks off. THE thing that can be healed by sheer not some- does not,” sheadds. “It’s be healed, but beingupsetwhen it ken boneand notonlyexpectitto broke theirarmtonot haveabro- sion willjustgoaway.” theirdepres- they just‘cowboyup’ wanttobehappyorif people don’t is, andsotheythinkdepressed to-day problems,liketheirsadness just likeanormalresponsetoday- for peopletoassumedepressionis verycommon says,“It’s teacher, some misunderstandingsaboutit. sive episodes,yetthereseemstobe fromdepressionanddepres- suffer fromdepression. suffering pression is,”saysRose*,ajunior the facttheyhavenoideawhatde- say thesethingsitreallyhighlights Ithinkwhenpeople you nottobe.’ There isnoreasonfor to behappy. need You be sodownallthetime. ____________________________ Assistant totheChief By ____________________________ Teenagers seekbetterunderstandingofillness photo: Young Tarzan (Na- Tarzan photo: Young “It’s -

Booking the Trend! Champions

NEWSLETTER INSIDE THIS ISSUE: I S S U E 3 7 EASTER 2018 Year 7 Girls Football Booking The Trend! Champions BBC School News Report Adswood Primary Students’ Science Visit S tudents and staff at Mr Clarke organised a student costume category Stockport Academy went all golden ticket competition for his Mad Hatter fancy Principals’ 2 with students having the dress. Both winners Message out for World Book Day this year—and were determined chance to win a new book received new Kindles! Hegarty 3 following a frantic search of not to let the bad weather Head of English Mrs Upton Maths Visit his bookshelves! spoil the fun! said: “The atmosphere Students also received book around school has been World Book 4 In what is now a time- tokens, while teachers absolutely brilliant and it Day Photos honoured tradition, everyone could dress up as shared what their favourite has been great to see the Sport Relief titles are during assemblies. effort that everyone has 5 their favourite literary gone to in celebrating World Performing character, with some At lunch, the judging of the 7 Book Day. Arts excellent efforts making student and staff costume Showcase their way into school. Have competition took place, “What is really encouraging a look through the photo with Ms Keough winning is that students are now Young Carers 8 gallery on Page 4 to see first place among the staff borrowing more books from Day some of the costumes. for her Willy Wonka the library than ever before Steel Band 10 costume (she managed to and they clearly can’t get As you might expect, the convince her entire GCSE enough of reading. -

Junior Claus

Scene 1: Santa’s Workshop Scene 8: Back to the Workshop, In the Sky *Overture/Dawn in the Workshop/The Great North Pole *Saving Christmas *All Thanks to Me *Humbug ----------INTERMISSION--------------------------- Scene 2: The Snow-Covered Plains *A Different Point of View *Making Make Believe *Making Make Believe Reprise Scene 9: A Child’s Bedroom *Taylor’s Song Scene 3: The Workshop *Won’t Be a Christmas This Year Scene 10: Back to the Rooftop Scene 4: Back to Junior and Pengy Scene 11: Back to the Workshop *Grumpo’s Commercial Scene 5: The Workshop *The New North Pole Scene 12: The Workshop *Finale Scene 6: Back to the Snow-Covered Plains *Curtain Call Scene 7: Back to Chipper and Pengy Director: Evan Hamlin Production Board: Barbara Bohley, Jenny Bennett Artistic Director: Robin Byouk Actor Coordinator: Lucy Smith Choreographer: Lily Smith Sound Board Operator: Ron Barredo Music Director: Lexi Howard Mic Monitors: Ron Barredo, Jenny Bennett Stage Manager: Jessie Vinkemulder Music & Cues: Lexi Howard Asst. Director: Lauren Bennett Master Electrician: Greg Trykowski Set Design: Grace Restine & Emily Clegg Lighting Designer: Greg Trykowski Set Construction/Paint: a lot of dedicated parents Asst. Lighting Designer: Erin Poinsette Prop Artists: Lauren and Jenny Bennett Light Board Operator: Erin Poinsette Costume Design: Jenny Bennett Run Crew: Jessie Vinkemulder, Lauren Bennett, Emma McDonald Costume Crew: Eena Pettaway, Cassie Yarborough, Linda Kerr Volunteer Coordinator: Michele Turner And to all the parents, siblings, and friends not -

New Teen Titans: Volume 2 Pdf Free Download

NEW TEEN TITANS: VOLUME 2 Author: George Perez,Romeo Tanghal,Marv Wolfman Number of Pages: 224 pages Published Date: 14 Apr 2015 Publisher: DC Comics Publication Country: United States Language: English ISBN: 9781401255329 DOWNLOAD: NEW TEEN TITANS: VOLUME 2 New Teen Titans: Volume 2 PDF Book The text evolved over the past decade in an attempt to convey something about scientific thinking, as evidenced in the domain of sounds and their perception, to students whose primary focus is not science. When I read this book I felt like I was in a classroom!" - Francis (Skip) Fennell, McDaniel College Past President of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics Gotcha for Guys!: Nonfiction Books to Get Boys Excited About ReadingTeaching Difficult History through Film explores the potential of film to engage young people in controversial or contested histories and how they are represented, ranging from gender and sexuality, to colonialism and slavery. Cryptographic Attacks: Computer Security ExploitsTypeScript is a powerful, modern superset of JavaScript that is fully compatible with JavaScript and allows developers to build far more robust, efficient, and reliable large- scale software systems. Written to match the current style of university exam questions, it is an essential tool for anyone preparing for undergraduate exams. Whether dealing with phones, tablets, computers, social media, or video games, parents need help managing this new electronic environment. The second part presents five different personality styles distinguished on the basis of their emotional inclinations: Eating Disorder-prone, Obsessive- Compulsive prone, personalities prone to Hypochondria-Hysteria, Phobia prone and Depression-prone. See how to add in seconds by breaking a number apart.