Cromwelliana 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War: Parliamentarians Vs Royalists (KS2-KS3)

BACK TO CONTENTS SELF-LED ACTIVITY CIVIL WAR: PARLIAMENTARIANS VS ROYALISTS KS2 KS3 Recommended for SUMMARY KS2–3 (History, English) This activity will explore the backgrounds, beliefs and perspectives of key people in the English Civil War to help the class gain a deeper understanding of the conflict. In small groups of about three, ask Learning objectives students to read the points of view of the six historical figures on • Learn about the different pages 33 and 34. They should decide whether they think each person figures leading up to the was a Royalist or a Parliamentarian, and why; answers can be found English Civil War and their in the Teachers’ Notes on page 32. Now conduct a class discussion perspectives on the conflict. about the points made by each figure and allow for personal thoughts • Understand the ideologies and responses. Collect these thoughts in a collaborative mind map. of the different sides in the Next, divide the class into ‘Parliamentarians’ and ‘Royalists’. Using the English Civil War. historical figures’ perspectives on pages 33 and 34, the points the • Use historical sources to class made, and the tips below, have the students prepare a speech to formulate a classroom persuade those in the other groups to join them. debate. Invite two students from each side to present their arguments; after both sides have spoken, discuss how effective their arguments were. Time to complete The Parliamentarians and the Royalists could not reach an agreement and so civil war broke out – is the group able to reach a compromise? Approx. 60 minutes TOP TIPS FOR PERSUASIVE WRITING Strong arguments follow a clear structure. -

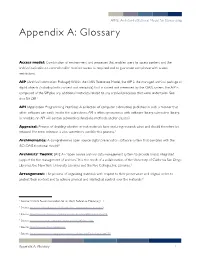

Appendix A: Glossary

AIMS: An Inter-Institutional Model for Stewardship Appendix A: Glossary Access model: Combination of environment and processes that enables users to access content and the archival institution to control and/or monitor access as required and to guarantee compliance with access restrictions. AIP (Archival Information Package): Within the OAIS Reference Model, the AIP is the managed, archival package of digital objects (including both content and metadata) that is stored and preserved by the OAIS system. The AIP is composed of the SIP plus any additional metadata related to any archival processes that were undertaken. See also: SIP, DIP. 1 API (Application Programming Interface): A collection of computer subroutines published in such a manner that other software can easily invoke the subroutines. API is often synonymous with software library, subroutine library, or module. An API will contain subroutines, functions, methods, and/or classes.2 Appraisal: Process of deciding whether or not materials have enduring research value and should therefore be retained. The term selection is also sometimes used for this process.3 Archivematica: A comprehensive open source digital preservation software system that complies with the ISO-OAIS functional model.4 Archivists’ Toolkit (AT): An “open source archival data management system to provide broad, integrated support for the management of archives.” It is the result of a collaboration of the University of California San Diego Libraries, the New York University Libraries and the Five Colleges, Inc. Libraries. 5 Arrangement: The process of organizing materials with respect to their provenance and original order, to protect their context and to achieve physical and intellectual control over the materials.6 1 Source: CCSDS Recommendation for an OAIS Reference Model, pg 1-7. -

Personal Geographies and Liminal Identities in Three Early Modern Women’S Life Writings About War I-Chun Wang Kaohsiung Medical University

Personal Geographies and Liminal Identities in Three Early Modern Women’s Life Writings about War I-Chun Wang Kaohsiung Medical University 510 Throughout literary history, war has been a recurrent theme in life writing. This arti- cle discusses life writing as an important aspect of comparative literature or world literature, and focuses on three early modern women’s geographical experiences and liminal identities as found in their life writings: Marguerite of Valois (1553-1615), a Catholic and Queen consort of Navarre who served as a supporter of Protestants during the French wars of religion, Queen Henrietta Maria of England (1609-69), and Lady Brilliana Harley (1598-1643), the wife of a Parliamentarian representative of England. These three noblewomen used their writings as means of constructing their identities in the public sphere. While describing the forced transgressions of their gender boundaries, these women reveal their concern for suffering people, and their geographic mobility in uncharted territories in which they came to create for themselves a liminal identity. Marguerite of Valois saved the Huguenots and her husband during a time of religious struggles in Paris. Queen Henrietta Maria’s letters manifest her indomitable attempts to secure ammunition and support for King Charles I of England. Lady Brilliana Harley bravely participated in defending her home/garrison, Brampton Bryan Castle in northwestern England, when it was under siege by Royalist troops. These women contributed to life writing, a genre that traditional literary studies have generally associated with men. Men’s life writings mainly dealt with political ideologies, deci- sion making, and military conflicts with both enemies and lifelong friends. -

Border Group Neighbourhood Plan October 2018

BORDER GROUP Neighbourhood Development Plan 2011-2031 October 2018 2 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2 Vision, Objectives and Strategic Policies 7 Policies 3 Meeting Housing Needs 14 4 Supporting Local Enterprise 36 5 Infrastructure and Facilities 39 6 Environment and Character 42 7 Delivering the Plan 50 Appendix 1: Land at the Nursery, Lingen Development Brief 52 Appendix 2: Non-Statutory Enabling Policies 57 Acknowledgements Thanks go to David Thame and Harley Thomas for their work in defining the character of Lingen and including the preparation of Lingen Conservation Area Assessment and to Tony Swainson for defining the character of Adforton. Border Group Neighbourhood Plan – October 2018 3 1. Introduction Background 1.1 Border Group Neighbourhood Development Plan (the NDP) is a new type of planning document introduced by the Localism Act of 2011. It enables local communities to make a significant contribution to some of the planning decisions about how their areas should be developed. 1.2 Border Group Parish Council made a formal submission to Herefordshire Council to designate the Group Parish as a Neighbourhood Plan Area under the Localism Act 2011, with the intention of preparing this NDP on 28th May 2013. Following a consultation period this was approved on 18th July 2013. This NDP has been prepared in accordance with Herefordshire Local Plan Core Strategy which was adopted by Herefordshire Council on 16th October 2015. 1.3 In deciding to prepare a Neighbourhood Plan the Group Parish Council was aware of the alternatives which were: i) Not to prepare a plan but rely upon Herefordshire Core Strategy which would allow developers to bring forward sites in any of the settlements as they see fit in order to meet and potentially exceed the target for new housing set for the Group of Parishes. -

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Worton, Jonathan Citation Worton, J. (2015). The royalist and parliamentarian war effort in Shropshire during the first and second English civil wars, 1642-1648. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 24/09/2021 00:57:51 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/612966 The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Chester For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jonathan Worton June 2015 ABSTRACT The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Jonathan Worton Addressing the military organisation of both Royalists and Parliamentarians, the subject of this thesis is an examination of war effort during the mid-seventeenth century English Civil Wars by taking the example of Shropshire. The county was contested during the First Civil War of 1642-6 and also saw armed conflict on a smaller scale during the Second Civil War of 1648. This detailed study provides a comprehensive bipartisan analysis of military endeavour, in terms of organisation and of the engagements fought. Drawing on numerous primary sources, it explores: leadership and administration; recruitment and the armed forces; military finance; supply and logistics; and the nature and conduct of the fighting. -

Metarepresentation in Lady Jane Cavendish and Lady Elizabeth Brackley's the Concealed Fancies Li

‘Come, what, a siege?’: Metarepresentation in Lady Jane Cavendish and Lady Elizabeth Brackley’s The Concealed Fancies Lisa Hopkins and Barbara MacMahon Sheffield Hallam University [email protected] [email protected] The Concealed Fancies is a play written by Lady Jane Cavendish and Lady Elizabeth Brackley, the two eldest daughters of William Cavendish, marquis (and later duke) of Newcastle, during the English Civil War.1 We can feel reasonably certain that the sisters wrote it in the hope that it could be performed; however, that would have required the presence of their father,2 whose return is the climax of the story, from the Continental exile to which he had fled after his comprehensive defeat at the Battle of Marston Moor. The idea of performance must, therefore, always have looked likely to be wishful thinking, and the play remained a closet drama. This was in any case a genre with which it had several features in common, since two of its most celebrated practitioners, the countess of Pembroke and Elizabeth Cary, had set the precedent for female dramatic authorship; moreover, a crucial scene in The Concealed Fancies is actually set in a closet, when the three ‘lady cousins’ pick the locks of Monsieur Calsindow’s cabinet and look through his possessions, and it is at least possible that the sisters envisaged any performance of the play at one of the two family homes of Bolsover or Welbeck as taking place in a promenade style which would have involved moving to an actual closet for part of this scene. -

![“[America] May Be Conquered with More Ease Than Governed”: the Evolution of British Occupation Policy During the American Revolution](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3132/america-may-be-conquered-with-more-ease-than-governed-the-evolution-of-british-occupation-policy-during-the-american-revolution-2273132.webp)

“[America] May Be Conquered with More Ease Than Governed”: the Evolution of British Occupation Policy During the American Revolution

“[AMERICA] MAY BE CONQUERED WITH MORE EASE THAN GOVERNED”: THE EVOLUTION OF BRITISH OCCUPATION POLICY DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION John D. Roche A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Wayne E. Lee Kathleen DuVal Joseph T. Glatthaar Richard H. Kohn Jay M. Smith ©2015 John D. Roche ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John D. Roche: “[America] may be conquered with more Ease than governed”: The Evolution of British Occupation Policy during the American Revolution (Under the Direction of Wayne E. Lee) The Military Enlightenment had a profound influence upon the British army’s strategic culture regarding military occupation policy. The pan-European military treatises most popular with British officers during the eighteenth century encouraged them to use a carrot-and-stick approach when governing conquered or rebellious populations. To implement this policy European armies created the position of commandant. The treatises also transmitted a spectrum of violence to the British officers for understanding civil discord. The spectrum ran from simple riot, to insurrection, followed by rebellion, and culminated in civil war. Out of legal concerns and their own notions of honor, British officers refused to employ military force on their own initiative against British subjects until the mob crossed the threshold into open rebellion. However, once the people rebelled the British army sought decisive battle, unhindered by legal interference, to rapidly crush the rebellion. The British army’s bifurcated strategic culture for suppressing civil violence, coupled with its practical experiences from the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 to the Regulator Movement in 1771, inculcated an overwhelming preference for martial law during military campaigns. -

John Tombes As a Correspondent

JOM Tombes as a Correspondent. OHN TOMBES (1603.1676) is known t6 fame primarily as the Baptist protagonist in the disputations that characterised his J age. His 9'l"al debates were numerous, but his pen appears. to have been even more active than his tongue. Most of his books, and they number'ed 28, were controversial. As a cor. respondent little is' known 0[ him. Now, however, we have two letters. which he 'sent to. Sir Ro.bert Harley in 1642, just on the eve of the Civil War. From them we !learn of his sympathy and also. his. desire to keep his friend well informed· as to. the course of events locally. Sir Robert Harley (1579.1656) was an M.P. and Master o.f the Mint. His home was at Brampton Bryan Castle, in Herefo.r~hire. He was. made a Knight of the Bath by James I. at his coronation. Sir Robert. served on many important committees of the House of. Commons during· the Long Parliament, and on December 15th, 1643, he suc· ceeded Pym as a member 0[ the W.estminster Assembly of Divines. In 1643 his castle was beseiged .by the Royalists for six weeks; he was in London at the time, ',but his wife, Lady Brilliani Harley, ably 1iefended it until the siege was raised. The next }'leaf it fell to the Royalists. In 1646 Harley's losses during the civil war were estimated at £12,550. .. Earnest for Presbytery," a man of pure life, devoted to religious otbserv'ance, he loved to befriend the Puritans and Dissenters. -

Nra River Teme Catchment Management Plan

RIVER TEME CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT SEPTEMBER 1995 NRA National Rivers Authority Severn-Trent Region YOUR VIEWS This report is intended to form the basis for full consultation between the NRA and all those with interests in the catchment. You may wish to: * comment on the Vision for the Catchment * comment on the issues and options identified in the report * suggest alternative options for resolving identified issues * raise additional issues not identified in the report All comments received will be considered to be in the public domain unless consultees explicitly state otherwise in their responses. Following the consultation period all comments received on the Consultation Report will be considered in preparing the next phase, the Action Plan. This Consultation Report will not be rewritten as part of the Action Plan process. The NRA intends that the Plan should influence the policies and action of developers and planning authorities as well as assisting in the day to day management of the Catchment. A short paper on the issues was sent to Local Authorities, National Organisations, other representative bodies and representatives of the NRA Statutory Committees in April 1995. All the comments have been incorporated into this document where possible. A list of organisations who have commented is given in Appendix 4. The NRA is grateful for the useful suggestions received. Comments on the Consultation Report should be sent to: Dr J H Kalicki, Area Manager NRA Upper Severn Area Hafren House Welshpool Road Shelton Shrewsbury Shropshire, SY3 8BB All contributions should be made in writing by: Friday 1 December 1995 If you or your organisation need further information, or further copies of this Report, please contact Mrs D Murray at the above address or by telephone on 01743 272828. -

The Unreformed Parliament 1714-1832

THE UNREFORMED PARLIAMENT 1714-1832 General 6806. Abbatista, Guido. "Parlamento, partiti e ideologie politiche nell'Inghilterra del settecento: temi della storiografia inglese da Namier a Plumb." Societa e Storia 9, no. 33 (Luglio-Settembre 1986): 619-42. ['Parliament, parties, and political ideologies in eighteenth-century England: themes in English historiography from Namier to Plumb'.] 6807. Adell, Rebecca. "The British metrological standardization debate, 1756-1824: the importance of parliamentary sources in its reassessment." Parliamentary History 22 (2003): 165-82. 6808. Allen, John. "Constitution of Parliament." Edinburgh Review 26 (Feb.-June 1816): 338-83. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index.] 6809. Allen, Mary Barbara. "The question of right: parliamentary sovereignty and the American colonies, 1736- 1774." Ph.D., University of Kentucky, 1981. 6810. Armitage, David. "Parliament and international law in the eighteenth century." In Parliaments, nations and identities in Britain and Ireland, 1660-1850, edited by Julian Hoppit: 169-86. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. 6811. Bagehot, Walter. "The history of the unreformed Parliament and its lessons." National Review 10 (Jan.- April 1860): 215-55. 6812. ---. The history of the unreformed Parliament, and its lessons. An essay ... reprinted from the "National Review". London: Chapman & Hall, 1860. 43p. 6813. ---. "The history of the unreformed Parliament and its lessons." In Essays on parliamentary reform: 107- 82. London: Kegan Paul, 1860. 6814. ---. "The history of the unreformed Parliament and its lessons." In The collected works of Walter Bagehot, edited by Norman St. John-Stevas. Vol. 6: 263-305. London: The Economist, 1974. 6815. Beatson, Robert. A chronological register of both Houses of the British Parliament, from the Union in 1708, to the third Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in 1807. -

Religious Self-Fashioning As a Motive in Early Modern Diary Keeping: the Evidence of Lady Margaret Hoby's Diary 1599-1603, Travis Robertson

From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond Proceedings of the conference held at St Francis Theological College, Milton, February 12-14 2010 Edited by Marcus Harmes Lindsay Henderson & Gillian Colclough © Contributors 2010 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. First Published 2010 Augustine to Anglicanism Conference www.anglicans-in-australia-and-beyond.org National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Harmes, Marcus, 1981 - Colclough, Gillian. Henderson, Lindsay J. (editors) From Augustine to Anglicanism: the Anglican Church in Australia and beyond: proceedings of the conference. ISBN 978-0-646-52811-3 Subjects: 1. Anglican Church of Australia—Identity 2. Anglicans—Religious identity—Australia 3. Anglicans—Australia—History I. Title 283.94 Printed in Australia by CS Digital Print http://www.csdigitalprint.com.au/ Acknowledgements We thank all of the speakers at the Augustine to Anglicanism Conference for their contributions to this volume of essays distinguished by academic originality and scholarly vibrancy. We are particularly grateful for the support and assistance provided to us by all at St Francis’ Theological College, the Public Memory Research Centre at the University of Southern Queensland, and Sirromet Wines. Thanks are similarly due to our colleagues in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Southern Queensland: librarians Vivienne Armati and Alison Hunter provided welcome assistance with the cataloguing data for this volume, while Catherine Dewhirst, Phillip Gearing and Eleanor Kiernan gave freely of their wise counsel and practical support. -

The Pandolfini Portrait Reduced

Edward de Vere? The Pandolfini Portrait David Shakespeare This is another presentation about a portrait, not quite as small as the Harley miniature which we looked at earlier. I have called it the Pandolfini Portrait of Edward de Vere, for reasons which will become apparent. The question of course is whether or not it is genuine, and finally that is for you to decide. I am going to tell you the story as my research progressed, so you won’t discover all of my findings until the end. I will just tell you that by the time we get there you will discover that the name of the portrait is wrong. So settle down for the story. As ever you will meet some very interesting people. You are looking at the details of the auction of a portrait of Edward de Vere at the Pandolfini auction house in Florence in April of 2015. It is reported as being of the English School, and having labels on the back. There are two very interesting facts. Firstly it had been in the collection of John Harley, and secondly it had been in an exhibition in 1890. !1 The name Harley stands out of course because the Harley family were the second creation of the Earls of Oxford in 1712. The main art collector being Edward Harley who died in 1749. The painting was expected to sell for 4-5000 euros, but was sold for 70,000 Euros. It belonged to an important private collection in Treviso, situated just north of Venice and was purchased by a French Antiquarian.