Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vision for Social Housing

Building for our future A vision for social housing The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing Building for our future: a vision for social housing 2 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Contents Contents The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing For more information on the research that 2 Foreword informs this report, 4 Our commissioners see: Shelter.org.uk/ socialhousing 6 Executive summary Chapter 1 The housing crisis Chapter 2 How have we got here? Some names have been 16 The Grenfell Tower fire: p22 p46 changed to protect the the background to the commission identity of individuals Chapter 1 22 The housing crisis Chapter 2 46 How have we got here? Chapter 3 56 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 3 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 4 The consequences of the decline p56 p70 Chapter 4 70 The consequences of the decline Chapter 5 86 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 90 Reforming social renting Chapter 7 Chapter 5 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 Reforming social renting 102 Reforming private renting p86 p90 Chapter 8 112 Building more social housing Recommendations 138 Recommendations Chapter 7 Reforming private renting Chapter 8 Building more social housing Recommendations p102 p112 p138 4 Building for our future: a vision for social housing 5 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Foreword Foreword Foreword Reverend Dr Mike Long, Chair of the commission In January 2018, the housing and homelessness charity For social housing to work as it should, a broad political Shelter brought together sixteen commissioners from consensus is needed. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for South Planning Committee, 24/09/2019 14:00

Shropshire Council Legal and Democratic Services Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Date: Monday, 16 September 2019 Committee: South Planning Committee Date: Tuesday, 24 September 2019 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Shrewsbury/Oswestry Room, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND You are requested to attend the above meeting. The Agenda is attached Claire Porter Director of Legal and Democratic Services (Monitoring Officer) Members of the Committee Substitute Members of the Committee Andy Boddington Roger Evans David Evans Nigel Hartin Simon Harris Christian Lea Nick Hignett Elliott Lynch Richard Huffer Dan Morris Cecilia Motley Kevin Pardy Tony Parsons William Parr Madge Shineton Kevin Turley Robert Tindall Claire Wild David Turner Leslie Winwood Tina Woodward Michael Wood Your Committee Officer is: Linda Jeavons Committee Officer Tel: 01743 257716 Email: [email protected] AGENDA 1 Election of Chairman To elect a Chairman for the ensuing year. 2 Apologies for Absence To receive any apologies for absence. 3 Appointment of Vice-Chairman To appoint a Vice-Chairman for the ensuing year. 4 Minutes To confirm the minutes of the South Planning Committee meeting held on 28 August 2019. TO FOLLOW Contact Linda Jeavons (01743) 257716. 5 Public Question Time To receive any questions or petitions from the public, notice of which has been given in accordance with Procedure Rule 14. The deadline for this meeting is no later than 2.00 pm on Friday, 20 September 2019. 6 Disclosable Pecuniary Interests Members are reminded that they must not participate in the discussion or voting on any matter in which they have a Disclosable Pecuniary Interest and should leave the room prior to the commencement of the debate. -

LIST of the PRINCIPAL SEATS in SHROPSHIRE, with Reference to the Places Under Which They Will Be Found in This Volume ----+

LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL SEATS IN SHROPSHIRE, With Reference to the Places under which they will be found in this Volume ----+----- PAGE PAGE Acton Burnell hall, Louis Gruning esq. see Acton Burnell 17 Caynham court, Sir William Michael Curtis bart. J.P. Acton Reynald hall, Sir Walter Orlando Corbet bart. see Caynham 51 D.L., J.P. see Acton Reynald, Shawbury 186 Caynton hall, James L. Greenway esq. J.P. see Beck- Acton Scotthall, Augustus Wood-Acton esq. D.L., J.P. bury 28 see Acton Scott...... 18 Cheswardine hall, Ralph Charles Donaldson-Hudson Adderley hall, Henry Reginald Corbet esq. D. L., J.P. esq. see Cheswardine 52 see Adderley 18 Chetwynd knoll,John Sidney Burton Borough esq.B.A., Albrighton hall, Alfred Charles Lyon esq. J.P. see J.P. see Chetwynd 54 Albrighton, near Wolverhampton 20 Chorley hall, Thomas Potter Carlisle esq. see Stot- Albrighton hall, WiIIiam Arthur Sparrowesq. J.P. see tesdon 236 Albrighton, near Shrewsbury... 21 Chyrch Preen Manor house, Arthur Sparrow esq. Aldenham hall, William Joseph Starkey Barber-Starkey F.S.A., D.L., J.P., see Church Preen 56 esg. see Morville 147 Chyknell, Henry Cavendish Cavendish esq. D.L., J.P. Apley castle, Col. Sir Thomas Meyrick bart. D.L., J.P. see Claverley 60 see Apley, Wellington 244 Clive hall, Thomas Meares esq. see Clive 65 Apley park, William Orme Foster esq. D.L., J.P. see Cloverley hall, Arthur Pemberton Heywood-Lonsdale Stockton;~....................................................... 233 esq. B.A., D.L., J.P. see Calverhall 49 Ashford Carbonell Manor house, Miss Hall, see Ashford Clungunford house, John Charles Leveson Rocke esq. -

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

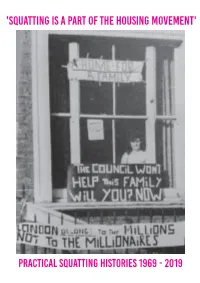

'Squatting Is a Part of the Housing Movement'

'Squatting Is A Part OF The HousinG Movement' PRACTICAL SQUATTING HISTORIES 1969 - 2019 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘...I learned how to crack window panes with a hammer muffled in a sock and then to undo the catch inside. Most houses were uninhabit- able, for they had already been dis- embowelled by the Council. The gas and electricity were disconnected, the toilets smashed...Finally we found a house near King’s Cross. It was a disused laundry, rather cramped and with a shopfront window...That night we changed the lock. Next day, we moved in. In the weeks that followed, the other derelict houses came to life as squatting spread. All the way up Caledonian Road corrugated iron was stripped from doors and windows; fresh paint appeared, and cats, flow- erpots, and bicycles; roughly printed posters offered housing advice and free pregnancy testing...’ Sidey Palenyendi and her daughters outside their new squatted home in June Guthrie, a character in the novel Finsbury Park, housed through the ‘Every Move You Make’, actions of Haringey Family Squatting Association, 1973 Alison Fell, 1984 Front Cover: 18th January 1969, Maggie O’Shannon & her two children squatted 7 Camelford Rd, Notting Hill. After 6 weeks she received a rent book! Maggie said ‘They might call me a troublemaker. Ok, if they do, I’m a trouble maker by fighting FOR the rights of the people...’ 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘Some want to continue living ‘normal lives,’ others to live ‘alternative’ lives, others to use squatting as a base for political action. -

2 Powys Local Development Plan Written Statement

Powys LDP 2011-2026: Deposit Draft with Focussed Changes and Further Focussed Changes plus Matters Arising Changes September 2017 2 Powys Local Development Plan 2011 – 2026 1/4/2011 to 31/3/2026 Written Statement Adopted April 2018 (Proposals & Inset Maps published separately) Adopted Powys Local Development Plan 2011-2026 This page left intentionally blank Cyngor Sir Powys County Council Adopted Powys Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Foreword I am pleased to introduce the Powys County Council Local Development Plan as adopted by the Council on 17th April 2017. I am sincerely grateful to the efforts of everyone who has helped contribute to the making of this Plan which is so important for the future of Powys. Importantly, the Plan sets out a clear and strong strategy for meeting the future needs of the county’s communities over the next decade. By focussing development on our market towns and largest villages, it provides the direction and certainty to support investment and enable economic opportunities to be seized, to grow and support viable service centres and for housing development to accommodate our growing and changing household needs. At the same time the Plan provides the protection for our outstanding and important natural, built and cultural environments that make Powys such an attractive and special place in which to live, work, visit and enjoy. Our efforts along with all our partners must now shift to delivering the Plan for the benefit of our communities. Councillor Martin Weale Portfolio Holder for Economy and Planning -

Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club

TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME XLVII 1993 PART III TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME XLVII 1993 PART III TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Proceedings, 1991 1 1992 .... - 129 1993 ■ - 277 Woolhope Room, by J. W. Tonkin - 15 Woolhope Club Badge - Carpet Bed, by Muriel Tonkin 17 George Marshall, by F. W. Pexton 18 An Early Motte and Enclosure at Upton Bishop, by Elizabeth Taylor 24 The Mortimers of Wigmore, 1214-1282, by Charles Hopkinson - 28 Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club 1993 The Old House, Vowchurch, by R. E. Rewell and J. T. Smith - 47 All contributions to The Woolhope Transactions are COPYRIGHT. None of them Herefordshire Street Ballads, by Roy Palmer .... 67 may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the writers. Applications to reproduce contributions, in whole or in Iron Age and Romano-British Farmland in the Herefordshire Area part, should be addressed in the first instance, to the editor whose address is given in 144 the LIST OF OFFICERS. by Ruth E. Richardson - The Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club is not responsible for any statement made, or Excavations at Kilpeck, Herefordshire, by R. Shoesmith - - .■ 162 opinion expressed, in these Transactions; the authors alone are responsible for their own papers and reports. John Nash and Humphry Repton: an encounter in Herefordshire by D. Whitehead - - - ..■ 210 Changes in Herefordshire during the Woolhope Years, by G. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1991 .................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME SEPTEMBER 1991 TO FEBRUARY 1992 ................................................... 3 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 3 MISCELLANY ....................................................................................................................... 4 BOOK REVIEW .................................................................................................................... 5 WORKERS EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE ............................................................................................................... 6 ANNUAL GARDEN PARTY .................................................................................................. 6 INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY MEETING, 15TH MAY, 1991 ................................................ 7 A FIELD SURVEY IN KIMBOLTON ...................................................................................... 7 FIND OF A QUERNSTONE AT CRASWALL ...................................................................... 10 BOLSTONE PARISH CHURCH .......................................................................................... 11 REDUNDANT CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF HEREFORD ........................................ 13 THE MILLS OF LEDBURY ................................................................................................. -

Annex E2 Visit Reports.Pdf

Annex E2 Final Report Working Group 1 – Engineers WG1: Report on visit to the Ledbury Estate, Peckham, Southwark November 30th 2018. The Ledbury Estate is in Peckham and includes four 14-storey Large Panel System (LPS) tower blocks. The estate belongs to Southwark Council. The buildings were built for the GLC between 1968 and 1970. The dates of construction as listed as Bromyard (1968), Sarnsfield (1969), Skenfrith (1969) and Peterchurch House (1970). The WG1 group visited Peterchurch House on November 30th 2018. The WG1 group was met by Tony Hunter, Head of Engineering, and, Stuart Davis, Director of Asset Management and Mike Tyrrell, Director of the Ledbury Estate. The Ledbury website https://www.southwark.gov.uk/housing/safety-in-the-home/fire-safety-on-the- ledbury-estate?chapter=2 includes the latest Fire Risk Assessments, the Arup Structural Reports and various Residents Voice documents. This allowed us a good understanding of the site situation before the visit. In addition, Tony Hunter sent us copies of various standard regulatory reports. Southwark use Rowanwood Apex Asset Management System to manage their regulatory and ppm work. Following the Structural Surveys carried out by Arup in November 2017 which advised that the tower construction was not adequate to withstand a gas explosion, all piped gas was removed from the Ledbury Estate and a distributed heat system installed with Heat Interface Units (HIU) in each flat. Currently fed by an external boiler system. A tour of Peterchurch House was made including a visit to an empty flat where the Arup investigation points could be seen. -

THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES of ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, Including Their Descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD

Rowlestone and Kentchurch Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES OF ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, including their descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD. edited by Linda Moffatt 2016© from the original work of Warren Skidmore CITATION Please respect the author's contribution and state where you found this information if you quote it. Suggested citation The Skydmores/ Scudamores of Rowlestone, Herefordshire, including their Descendants at Kentchurch, Llancillo, Magor & Ewyas Harold, ed. Linda Moffatt 2016, at the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com'. DATES • Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. • Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

Hlhs Herefordshire Local History Societies

HLHS HEREFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES Events, news, reviews September – November 2017 No.14 Editor: Margot Miller – Fownhope [email protected] Re-Enactment of Battle of Mortimers Cross 1461 9 and 10 September – Saturday & Sunday - Croft Castle NT Closing day for news & events for January 2018 HLHS emailing - Friday 15 December 2017 In this emailing: HARC events; Rotherwas Royal Ordnance Project & Kate Adie at the Courtyard Theatre; River Voices – oral history from the banks of the Wye; Shire Hall Centenary; Herefordshire Heritage Open Days; Rotherwas Chapel; Michaelchurch Court, St Owens Cross; Ashperton Heritage Trail; h.Art church exhibitions – Llangarron, Kings Caple & Hoarwithy; Mortimer History Society Symposium; Wigmore Centre public meeting; Re-Enactment of Battle of Mortimers Cross, Ross Walking Festival; WEA Autumn Courses, Hentland Conservation Project, Hereford Cathedral Library lectures and Cathedral Magna Carta exhibition; Woolhope Club visits; The Master’s House, Ledbury; Autumn programmes from history group - Bromyard, Eaton Bishop, Fownhope, Garway, Leominster, Longtown, Ross-on-Wye; David Garrick Anniversary Study Day at Hereford Museum Resource & Learning Centre, Friar Street. HARC EVENTS SEPTEMBER to NOVEMBER 2017 HARC, Fir Tree Lane, HR2 6LA, [email protected] 01432.260750 Booking: to reserve a place, all bookings in advance by email, phone or post Brochure of all upcoming events available by email or snail mail Friday 1st September: Rhys Griffith on Unearthing your Herefordshire Roots - a beginners guide on how to research your family history. 10.30-11.30am £6 Friday 15 September: Philip Bouchier – Behind the Scenes Tour 2-3pm £6 Monday 25 September: Philip Bouchier – Discovering the records of Hereford Diocese 10.30am-12.30pm £9.60 Wednesday 27 September: Elizabeth Semper O’Keefe - Anno Domini: an instruction to dating systems in archival documents. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump)