Der Computeranimierte Spielfilm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Computeranimierte Spielfilm. Forschungen Zur Inszenierung Und Klassifizierung Des 3-D-Computer-Trickfilms

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Klaus Kohlmann Der computeranimierte Spielfilm. Forschungen zur Inszenierung und Klassifizierung des 3-D-Computer- Trickfilms 2007 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/866 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kohlmann, Klaus: Der computeranimierte Spielfilm. Forschungen zur Inszenierung und Klassifizierung des 3-D-Computer- Trickfilms. Bielefeld: transcript 2007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/866. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839406359 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 3.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 3.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Klaus Kohlmann Der computeranimierte Spielfilm Klaus Kohlmann (Dr. phil.) arbeitet als 3-D-Artist für mehrere Agen- turen sowie als Autor für Fachmagazine. Er ist Universitätslehrbe- auftragter für 3-D-Computergrafik. (www.klauskohlmann.de) Klaus Kohlmann Der computeranimierte Spielfilm. Forschungen zur Inszenierung und Klassifizierung des 3-D-Computer-Trickfilms Das Buch ist eine von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln angenommene Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades -

Forsíða Ritgerða

Hugvísindasvið The Thematic and Stylistic Differences found in Walt Disney and Ozamu Tezuka A Comparative Study of Snow White and Astro Boy Ritgerð til BA í Japönsku Máli og Menningu Jón Rafn Oddsson September 2013 1 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt Mál og Menning The Thematic and Stylistic Differences found in Walt Disney and Ozamu Tezuka A Comparative Study of Snow White and Astro Boy Ritgerð til BA / MA-prófs í Japönsku Máli og Menningu Jón Rafn Oddsson Kt.: 041089-2619 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2013 2 Abstract This thesis will be a comparative study on animators Walt Disney and Osamu Tezuka with a focus on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Astro Boy (1963) respectively. The focus will be on the difference in story themes and style as well as analyzing the different ideologies those two held in regards to animation. This will be achieved through examining and analyzing not only the history of both men but also the early history of animation in Japan and USA respectively. Finally, a comparison of those two works will be done in order to show how the cultural differences affected the creation of those products. 3 Chapter Outline 1. Introduction ____________________________________________5 1.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________5 1.2 Thesis Outline _________________________________________________5 2. Definitions and perception_________________________________6 3. History of Anime in Japan_________________________________8 3.1 Early Years____________________________________________________8 -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Blue Screen Matting

Blue Screen Matting Alvy Ray Smith and James F. Blinn Microsoft Corporation ABSTRACT allowed to pass through and illuminate those parts desired but is blocked everywhere else. A holdout matte is the complement: It is A classical problem of imaging—the matting problem—is separa- opaque in the parts of interest and transparent elsewhere. In both tion of a non-rectangular foreground image from a (usually) rectan- cases, partially dense regions allow some light through. Hence gular background image—for example, in a film frame, extraction of some of the color film image that is being matted is partially illu- an actor from a background scene to allow substitution of a differ- minated. ent background. Of the several attacks on this difficult and persis- The use of an alpha channel to form arbitrary compositions of tent problem, we discuss here only the special case of separating a images is well-known in computer graphics [9]. An alpha channel desired foreground image from a background of a constant, or al- gives shape and transparency to a color image. It is the digital most constant, backing color. This backing color has often been equivalent of a holdout matte—a grayscale channel that has full blue, so the problem, and its solution, have been called blue screen value pixels (for opaque) at corresponding pixels in the color image matting. However, other backing colors, such as yellow or (in- that are to be seen, and zero valued pixels (for transparent) at creasingly) green, have also been used, so we often generalize to corresponding color pixels not to be seen. -

Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing

Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing Technical Memo 7 Alvy Ray Smith August 15, 1995 Abstract The history of digital image compositing—other than simple digital imple- mentation of known film art—is essentially the history of the alpha channel. Dis- tinctions are drawn between digital printing and digital compositing, between matte creation and matte usage, and between (binary) masking and (subtle) mat- ting. The history of the integral alpha channel and premultiplied alpha ideas are pre- sented and their importance in the development of digital compositing in its cur- rent modern form is made clear. Basic Definitions Digital compositing is often confused with several related technologies. Here we distinguish compositing from printing and matte creation—eg, blue-screen matting. Printing v Compositing Digital film printing is the transfer, under digital computer control, of an im- age stored in digital form to standard chemical, analog movie film. It requires a sophisticated understanding of film characteristics, light source characteristics, precision film movements, film sizes, filter characteristics, precision scanning de- vices, and digital computer control. We had to solve all these for the Lucasfilm laser-based digital film printer—that happened to be a digital film input scanner too. My colleague David DiFrancesco was honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Art and Sciences last year with a technical award for his achievement on the scanning side at Lucasfilm (along with Gary Starkweather). Also honored was Gary Demos for his CRT-based digital film scanner (along with Dan Cam- eron). Digital printing is the generalization of this technology to other media, such as video and paper. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly Mcgill BA, University Of

Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly McGill B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art & Art History 2018 i This thesis entitled: Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History written by Molly McGill has been approved for the Department of Art and Art History Date (Dr. Brianne Cohen) (Dr. Kirk Ambrose) (Dr. Denice Walker) The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Department of Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder for their continued support during the production of this master's thesis. I am truly grateful to be a part of a department that is open to non-traditional art historical exploration and appreciate everyone who offered up their support. A special thank you to my advisor Dr. Brianne Cohen for all her guidance and assistance with the production of this thesis. Your supervision has been indispensable, and I will be forever grateful for the way you jumped onto this project and showed your support. Further, I would like to thank Dr. Kirk Ambrose and Dr. Denice Walker for their presence on my committee and their valuable input. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Catherine Cartwright and Jean Goldstein for listening to all my stress and acting as my second moms while I am so far away from my own family. -

Richer Worlds for Next Gen Games: Data Amplification Techniques Survey

Richer Worlds for Next Gen Games: Data Amplification Techniques Survey Natalya Tatarchuk 3D Application Research Group ATI Research, Inc. Overview • Defining the problem and motivation • Data Amplification • Procedural data generation • Geometry amplification • Data streaming • Data simplification • Conclusion Overview • Defining the problem and motivation • Data Amplification • Procedural data generation • Geometry amplification • Data streaming • Data simplification • Conclusion Games and Current Hardware • Games currently are CPU-limited – Tuned until they are not GPU-limited – CPU performance increases have slowed down (clock speed hit brick walls) – Multicore is used in limited ways Trends in Games Today • Market demands larger, more complex game worlds – Details, details, details • Existing games already see increase in game data – Data storage progression: Floppies → CDs → DVDs – HALO2.0 - 4.2GB – HD-DVD/Blueray → 20GB [David Blythe, MS Meltdown 2005] Motivation • GPU performance increased tremendously over the years – Parallel architecture allows consumption of ever increasing amounts of data and fast processing – Major architectural changes happen roughly every 2 years – 2x speed increase also every 2 years – Current games tend to be • Arithmetic limited (shader limited) • Memory limited • GPUs can consume ever increasing amounts of data, producing high fidelity images – GPU-based geometry generation is on the horizon – Next gen consoles Why Not Just Author A Ton of Assets? • Rising development cost – Content creation is the bottleneck -

Hereby the Screen Stands in For, and Thereby Occludes, the Deeper Workings of the Computer Itself

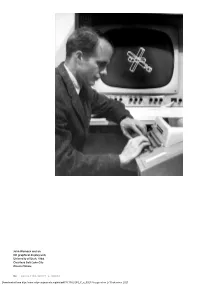

John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00233 by guest on 27 September 2021 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. 4 But the computer screen was also a cathode ray tube (CRT) phosphorescing in response to an electron beam, modified by a grid of randomly accessible memory that stores, maps, and transforms thousands of bits in real time. The screen is not simply an enduring technique or evocative metaphor; it is a hardware object whose transformations have shaped the ma - terial conditions of our visual culture. -

Reader 19 05 19 V75 Timeline Pagination

Plant Trivia TimeLine A Chronology of Plants and People The TimeLine presents world history from a botanical viewpoint. It includes brief stories of plant discovery and use that describe the roles of plants and plant science in human civilization. The Time- Line also provides you as an individual the opportunity to reflect on how the history of human interaction with the plant world has shaped and impacted your own life and heritage. Information included comes from secondary sources and compila- tions, which are cited. The author continues to chart events for the TimeLine and appreciates your critique of the many entries as well as suggestions for additions and improvements to the topics cov- ered. Send comments to planted[at]huntington.org 345 Million. This time marks the beginning of the Mississippian period. Together with the Pennsylvanian which followed (through to 225 million years BP), the two periods consti- BP tute the age of coal - often called the Carboniferous. 136 Million. With deposits from the Cretaceous period we see the first evidence of flower- 5-15 Billion+ 6 December. Carbon (the basis of organic life), oxygen, and other elements ing plants. (Bold, Alexopoulos, & Delevoryas, 1980) were created from hydrogen and helium in the fury of burning supernovae. Having arisen when the stars were formed, the elements of which life is built, and thus we ourselves, 49 Million. The Azolla Event (AE). Hypothetically, Earth experienced a melting of Arctic might be thought of as stardust. (Dauber & Muller, 1996) ice and consequent formation of a layered freshwater ocean which supported massive prolif- eration of the fern Azolla. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß.