Evaluation of UNHCR's Livelihoods Strategies and Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom to Write Index 2019

FREEDOM TO WRITE INDEX 2019 Freedom to Write Index 2019 1 INTRODUCTION mid global retrenchment on human rights In 2019, countries in the Asia-Pacific region impris- Aand fundamental freedoms—deepening oned or detained 100 writers, or 42 percent of the authoritarianism in Russia, China, and much of the total number captured in the Index, while countries Middle East; democratic retreat in parts of Eastern in the Middle East and North Africa imprisoned or Europe, Latin America, and Asia; and new threats detained 73 writers, or 31 percent. Together these in established democracies in North America and two regions accounted for almost three-quarters Western Europe—the brave individuals who speak (73 percent) of the cases in the 2019 Index. Europe out, challenge tyranny, and make the intellectual and Central Asia was the third highest region, with case for freedom are on the front line of the battle 41 imprisoned/detained writers, or 17 percent of to keep societies open, defend the truth, and resist the 2019 Index; Turkey alone accounted for 30 of repression. Writers and intellectuals are often those cases. By contrast, incarceration of writers is among the canaries in the coal mine who, alongside relatively less prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, with journalists and human rights activists, are first 20 writers, or roughly eight percent of the count, and targeted when a country takes a more authoritarian the Americas, with four writers, just under two percent turn. The unjust detention and imprisonment of the count. The vast majority of imprisoned writers, of writers and intellectuals impacts both the intellectuals, and public commentators are men, but individuals themselves and the broader public, who women comprised 16 percent of all cases counted in are deprived of innovative and influential voices the 2019 Index. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

CGWR and the Global Labour University

We are a Center! On December 1, 2012, the College of the Liberal Arts formally promoted us from a project to a research center. We are now the Center for Global Workers’ Rights (CGWR) at Penn State University. In the spring 2013 semester, the CGWR is looking forward to hosting more speakers, organizing an international workshop with US and international unionists to discuss the Global Labour University, and holding a major scholar-practitioner international symposium on precarious work. In addition, the CGWR will facilitate a series of initiatives for students, faculty, and practitioners designed to promote global workers’ rights. And with the goal of increasing the impact of our research, the CGWR will continue to partner with other universities, labor unions, and NGOs to produce action-oriented research projects on topics such as workers’ rights in Colombia and El Salvador. Brick worker in Bangladesh; Write us if you have any thoughts or questions about the CGWR’s work photo by Arifur Rahman and join our listserv in order to stay on top of the latest events: <[email protected]>. Visit our website http://lser.la.psu.edu/gwr/. Or, find us on Facebook: "The Penn State Center for Global Workers' Rights." CGWR and the Global Labour University In order to further encourage the study of global workers’ rights, the CGWR has initiated a relationship with the Global Labour University (GLU). GLU is a network of universities that offer Master’s degrees in labor and globalization. GLU students are mid-career labor unionists or practitioners. Through the program, students gain knowledge of international labor standards and trade unions, sustainable development, social justice, and global institutions. -

The Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression

The Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression editorial 2—6 Freedom of Speech and Expression Under Threat published by spotlight 6—15 the asian-pacific resource and research centre for women (arrow) Feminists Navigating Digital resources from the arrow Space and Countering srhr knowledge sharing Technology ‘Enabling’ centre 26—28 Violence other resources 29—30 “Rape Her”: Gendered Hate monitoring countries and Speech Against Rohingya regional activities 19—25 published with the funding Women definitions 30—31 support of Does the Digital Security Act Lip Sync to Jail Increase Insecurity for People factfile 31—34 in Bangladesh? Equal Before God?: Women Freedom of Speech and and the Right to Freedom of Fiji’s Online Safety Act Expression and Sexual and Religion Reproductive Health and The Challenge of Protecting Rights: Connections and Free Speech in Duterte’s Contemporary Context in the Asia Pacific Region arrow receives institutional in our own words 16—18 Philippines support from the Ford Foundation and the Foundation for a Just Working Around Media The Blasphemy Regime in editorial and Society Censorship to Tell Our Stories Pakistan production team 36 2 arrow for change | vol. 26 no. 1 2020 editorial By Rachel Arinii FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND East-Asia and ASEAN Programme Manager, FORUM-ASIA EXPRESSION UNDER THREAT Email: [email protected] This editorial was created by extracting expression. While platforms are available, Part II: Freedom of Speech and information from FORUM-ASIA’s the uneven distribution in the access Expression in East Asia – Freedom of publication titled, “The Instrument of to, use of, or impact of information expression is heavily restricted in East Repressions: Regional Report on the technologies severely affect women Asia. -

Sunday 17 October 2021

DAY 1 – SUNDAY 17 OCTOBER 2021 13:15 - 14:45 Grand opening of the virtual exhibition Exhibitor Breaking News Sessions on the Virtual Meeting Platform 13:15 BioLegend: What’s new from BioLegend for ICIS/Cytokines 2021? 13:30 ICIS: Learn about opportunities for Cytokines 2022 Hawaii ! 13:45 • Cytokine Signalling Forum: An overview of the Cytokine Signalling Forum • Quanterix: High definition multiplex measurement of cytokines & interferons with Simoa® • Olink: Next Generation Proteomics 14:00 • PBL: Human Interleukin Products providing accurate endogenous quantitation • GSK: Live Discussion with Immunology Network Postdoc • 10X Genomics: High resolution characterisation of the immune system 14:15 • Pfizer: Post-doctoral Program • Humanigen: LIVE-AIR Data presentation • Xilio: Learn More About Xilio Therapeutics 14:30 • Boehringer Ingelheim: opnMe.com: The open Innovation portal of Boehringer Ingelheim • The Korean Association of Immunologists (KAI): Supports Young Investigators! • Luminex: The New xMAP® INTELLIFLEX: Technology You Trust. Versatility You Want 15:00 - 17:30 Opening Session (Sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from Bristol Myers Squibb) 15:00 Welcome and opening remarks / Simon Jones (University of Cardiff, UK) 15:05 President’s address and presentation of ICIS Awards / Kate Fitzgerald (University of Massachusetts Medical School, US) 15:10 Award Ceremony – Presentations & Ceremony ICIS Senior & Mid-Career and Young Investigator Awards • ICIS-Mentorship Award / Howard A. Young (NIH, US) • ICIS-Distinguished Services Award / Nancy C. Reich Marshall (Stony Brook University, US) • ICIS-Honorary Lifetime Membership Award / Carl F. Ware (Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, US) 1 All sessions are in Cardiff, UK, Local Time (GMT+1) • Regeneron New Investigator Awards for Excellence in Cytokine & Interferon Research (formerly the Milstein Young Investigator Awards) o Rebecca C. -

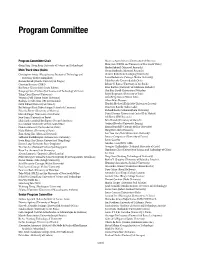

Program Committee

Program Committee Program Committee Chair Mauricio Ayala-Rincón (Universidade de Brasilia) Qiang Yang (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) Haris Aziz (NICTA and University of New South Wales) Moshe Babaioff (Microso Research) Main Track Area Chairs Yoram Bachrach (Microso Research) Christopher Amato (Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Christer Bäckström (Linköping University) University of New Hampshire) Laura Barbulescu (Carnegie Mellon University) Roman Bartak (Charles University in Prague) Pablo Barcelo (Universidad de Chile) Christian Bessiere (CNRS) Leliane N. Barros (University of Sao Paulo) Blai Bonet (Universidad Simón Bolívar) Peter Bartlett (University of California, Berkeley) Xiaoping Chen (University of Science and Technology of China) Shai Ben-David (University of Waterloo) Yiling Chen (Harvard University) Ralph Bergmann (University of Trier) Veronica Dahl (Simon Fraser University) Alina Beygelzimer (Yahoo! Labs) Rodrigo de Salvo Braz (SRI International) Albert Bifet (Huawei) Edith Elkind (University of Oxford) Hendrik Blockeel (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) Boi Faltings (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne) Francesco Bonchi (Yahoo Labs) Eduardo Ferme (University of Madeira) Richard Booth (Mahasarakham University) Marcelo Finger (University of Sao Paulo) Daniel Borrajo (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Joao Gama (University of Porto) Adi Botea (IBM Research) Lluis Godo (Artificial Intelligence Research Institute) Felix Brandt (University of Munich) Jose Guivant (University of New South Wales) Gerhard -

Do Stock Prices in Turkey Reflect Fundamental Information? a Firm-Level Analysis

International Journal of Economics and Finance; Vol. 4, No. 12; 2012 ISSN 1916-971X E-ISSN 1916-9728 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Do Stock Prices in Turkey Reflect Fundamental Information? A Firm-level Analysis M. Arifur Rahman1, M. Shibley Sadique2 & Shah Saeed Hassan Chowdhury3 1 Faculty of Business, Economics & Policy Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Brunei Darussalam 2 Department Finance and Banking, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh 3 Department of Accounting and Finance, Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: M. Arifur Rahman, Faculty of Business, Economics & Policy Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Gadong BE1410, Brunei Darussalam. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 6, 2012 Accepted: October 20, 2012 Online Published: October 31, 2012 doi:10.5539/ijef.v4n12p137 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v4n12p137 Abstract This paper investigates the correspondence between stock prices and firm fundamentals in Turkey. In pursuing our objective, we explore the relationship between firm-specific variation in stock returns and fundamentals in the context of a simple present value framework. We overcome the typical insufficiency of the spans of time-series accounting data in emerging market research, and the consequent loss of statistical testing power, by adopting a firm-level micro panel data approach. After properly accounting for unobserved heterogeneity, potential endogeneity bias and volatility persistence, we find that firm-specific variation of stock returns in Turkey is only weakly correlated with alternative proxies of firm-specific variation in firm fundamentals and that the relationship is not robust to the influence of control variables such as the firm size. -

Golaghat in the Court of the Chief Judicial Magistrate, Golaghat

1 DISTRICT :: GOLAGHAT IN THE COURT OF THE CHIEF JUDICIAL MAGISTRATE, GOLAGHAT Misc. (DV) Case No. 61/2018 Smti Bimala Thapa ……………………………Petitioner Vs. 1. Md. Arifur Rahman 2. Zahida Begum And 3. Md. Moti Rahman …………………………Respondents PRESENT: Sri Kiran Lal Baishnab, AJS Chief Judicial Magistrate, Golaghat. For the Petitioner :: Mr. J.K. Goswami and Smti S. Boruah, Advocates For the Respondents :: Md. I. Hussain, Advocate Evidence Recorded on : 29.12.2018, 21.01.2019, 21.06.2019, 11.07.2019, 14.08.2019, 19.09.2019, 29.11.2019 and 19.12.2019 Date of Argument : 29.01.2021 Date of Judgment : 12.02.2021 JUDGMENT 1. The case of the petitioner Smti Bimala Thapa is that she was married to the Respondent No.1 Md. Arifur Rahman at Guwahati after eloping with him on 14/01/2018 as they had love affairs. It is averred by the petitioner that after their marriage the Respondent No.1 took her to his house at Jurbari, Dergaon and resided there with Page 1 of 14 2 him as husband and wife and just after 4 days of her return to her parental house the Respondent No.1 and Respondent No.2 started torturing her physically and mentally for not bringing article on dowry and that in the said act of the Respondent No.1 and Respondent No.2; the Respondent No.3 had given instigation and the Respondent No.2 Miss Zahida Begum even slapped the victim for not bringing any article from her paternal house. She further averred that the Respondent No.2 not only assaulted her with hand but even harassed her emotionally by abusing her stating that she being a girl of beggars family she did not bring anything and the Respondents even force her to eat beef and when she vomited upon forceful eating of beef the Respondent No.1 and Respondent No.2 assaulted her. -

Bangladesh Page 1 of 30

2010 Human Rights Report: Bangladesh Page 1 of 30 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » Human Rights Reports » 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices » South and Central Asia » Bangladesh 2010 Human Rights Report: Bangladesh BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices April 8, 2011 Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy of 155 million citizens. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed leads the Awami League (AL) alliance, a 14-party coalition with a large majority of parliamentary seats. International and domestic observers considered the 2008 elections to be free and fair, with isolated irregularities and sporadic violence. There were instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Security forces committed extrajudicial killings and were responsible for custodial deaths, torture, and arbitrary arrest and detention. The failure to investigate fully extrajudicial killings by security forces, including several deaths in custody of alleged criminals detained by the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), remained a matter of serious concern. Some members of the security forces acted with impunity. Prison conditions at times were life-threatening, lengthy pretrial detention continued to be a problem, and authorities infringed on citizens' privacy rights. An increasingly politicized judiciary exacerbated problems in an already overwhelmed judicial system and constrained access to justice for members of opposition parties. The government limited freedom of speech and of the press, self-censorship continued, and security forces harassed journalists. The government curbed freedom of assembly, and politically motivated violence remained a problem. Official corruption and related impunity continued. -

ICORN Programme for 2017 Joint Biennial PEN International Wipc Conference and ICORN Network Meeting

ICORN Programme for 2017 joint biennial PEN International WiPC Conference and ICORN Network Meeting ICORN PROGRAMME ________________________________________________________ When freedom of expression is threatened, curtailed or outlawed, artists and writers are compelled to find ever more inventive ways to evade authoritarian repression. New forms, new words, new means of resistance emerge at every turn and in every language. ‘In Other Words’, the joint ICORN network meeting & PEN International WiPC conference in Lillehammer in May 2017, is an exploration and a celebration of the resilience of art and literature in the face of a ‘post truth’ world. More than 300 writers, artists, activists, city representatives and other guests from 60 countries will engage with the festival public in seminars, workshops, readings, concerts and manifestations. Topics such as “Guantanamo Diary live”, “One day in Aleppo”, “Freedom of expression in a post truth world” and “The landscape of residencies” will be on the agenda, along with fresh eyewitness reports from areas where writers, artists and human rights defenders are most threatened. ICORN and PEN International is thrilled to be able to integrate our major biennial joint event into the programme of the Norwegian Festival of Literature (30 May – 4 June). The programming of both events are duly coordinated, and we already see the mutual benefits emerge. ________________________________________________________ Accommodation and main Venue: Scandic Lillehammer Hotel Organisers: ICORN, the International -

![Commencement Program [Undergraduate Spring 2003]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9046/commencement-program-undergraduate-spring-2003-3979046.webp)

Commencement Program [Undergraduate Spring 2003]

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Commencement Programs University Archives 5-11-2003 Commencement Program [Undergraduate Spring 2003] St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/commpro Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation St. Cloud State University, "Commencement Program [Undergraduate Spring 2003]" (2003). Commencement Programs. 230. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/commpro/230 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPRING SEMESTER COMMENCEMENT for undergraduates Sunday, May Eleventh Two thousand three Two p.m. National Hockey Center St. Cloud State University COMMENCEMENT MARKS RENEWAL OF SCSU TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE AND OPPORTUNITY 1871 graduate Alfretta Van Valkenberg, a member ceremony the academic and practical knowledge of the first class of the Third Normal School (later they had gained to prepare them for a career and St. Cloud State University), recalled years later the for life . They would be reminded of the issues they vivid memory and dramatic impact of her com had explored and the opinions they had formulat mencement: "I felt all of life was open to me and I ed. They would celebrate the friends they had met could tread (life's) paths with a firm and reliant from different backgrounds and diverse cultures. tread." Today's graduates are the latest to benefit from The environment on this campus has changed the tradition of excellence and opportunity that significantly since Alfretta received her diploma. -

Task Order No. 817 Under the GBTI IQC No. PCE-I-00-98-00015-00

BANGLADESH ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT ASSESSMENT REPORT Task Order No. 817 Under the GBTI IQC No. PCE-I-00-98-00015-00 Volume Two: Annexes A - L Submitted to: USAID Submitted by: Chemonics International Inc. December 2001 Dhaka, Bangladesh TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME TWO: ANNEXES ANNEX A: PERSONS INTERVIEWED ANNEX B: BIBLIOGRAPHY ANNEX C: STATEMENT OF WORK ANNEX D: PROFILES OF THE ASSESSMENT TEAM ANNEX E: THE TECHNICAL APPROACH TO THE ASSESSMENT ANNEX F: THE SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE ANNEX G: FOCUS GROUPS ANNEX H: LEGACY FOOTWEAR STUDY ANNEX I: JOBS R4 RECAP ANNEX J: BRAC PROPOSAL ON VOCATIONAL TRAINING ANNEX K: USAID FUNDED ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS ANNEX L: NON-USAID FUNDED SME PROJECTS CHEMONICS INTERNATIONAL INC. ACRONYMS ACF-DF Agribusiness Credit Fund-Development Fund ADAB Association for Development Agencies in Bangladesh ADB Asian Development Bank ASA Association of Social Advancement ASEAN Association of South East Asian Nations ATDP-I Agro-based Industries and Technology Development Project-I (1995-2000) ATDP-II Agro-based Industries and Technology Development Project-II (2000-2004) BASC Business Advisory Services Center BASIC Bank of Small Industries and Commerce Corporation BB Bangladesh Bank (Central Bank) BBS Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics BDS Business Development Services BDSP-B Business Development Services Program-Bangladesh (Swiss Contact) BFFEA Bangladesh Frozen Food Export Association BGMEA Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Employers Association BHB Bangladesh Handloom Board BIDS Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies