Reg Guide 2004 REVISED V7.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The G20 at Hmc Boston

Harvard Model Congress Boston 2020 GUIDE TO THE G20 Edited by Ravi Shah and Harnek Gulati INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Group of Twenty! The G20 is a forum for the world’s nineteen largest economies—Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States, plus the European Union. The group allows for dialogue among the world’s most advanced and emerging economies. The group’s main tasks consist of addressing global economic and financial issues—at least one delegate at the conference will represent each country. You, the delegates at HMC 2019, will play the roles of these officials, representing their respective governments or institutions during the summit. At this time of global financial crisis and economic slowdown, the G20 has been instrumental to the stabilization of the international financial system and the coordination of macroeconomic policies among the most important economic players in the international arena. During our conference, you will represent the opinions of their governments on political and environmental matters, bringing each government’s perspective regarding the restoration of political stability and environmental sustainability to the table. You are expected to challenge each other on political matters in order to defend the interests of your respective countries, all while keeping global cooperation and the elaboration of a common strategy as your ultimate goals. HISTORY OF THE G20 The G20 was founded in 1999 as a response to the financial crises of the late 1990s. It replaced the short-lived G33 and G22. -

Kennedy's Cabinet, 1961

KENNEDY’S CABINET, 1961 By Anthony Colarusso and Georgia Steigerwald INTRODUCTION The year is 1961, and President John F. Kennedy has just been inaugurated. He will rely on all of you, his cabinet, to help him guide the United States through these trying times. The United States is facing a Cold War with the Soviet Union that has changed the global geopolitical landscape, as well as significant domestic issues regarding civil rights and social reforms. These issues have put President Kennedy in a position to define the future of the United States in many ways through his choice of actions. Your advice as a President Kennedy’s cabinet will be essential to ensuring that the United States navigates inaugural address. difficult decisions and prevents the nation, and even the world, from CBS plunging into conflict and unrest. THE SPACE RACE Explanation of the Issue Historical Development The mission to The United States’ journey to space thus far has been a long and put an American difficult process. Engineers struggle to design machines that can in space will be withstand extreme temperatures and successfully make it to space no easy task. and back. Scientists address the problems of sustaining life in space. Thousands work to create facilities and equipment. A handful of “astronauts” train for a mission unlike any they’ve ever flown before. The Birth of NASA For the military, the 1950s were characterized by the development of missile and nuclear propulsion technology (Dunbar). HARVARD MODEL CONGRESS The Air Force facilitated the testing of new missiles at their Cape Canaveral Station, while the Army had its own Army Ballistic Missile Agency to conduct research (Ward). -

URBAN PLANNING by Akila Muthukumar

URBAN PLANNING By Akila Muthukumar INTRODUCTION New York City. Los Angeles. Chicago. Miami. Philadelphia. Dallas. Atlanta. Boston. These are just a few of America’s metro centers. According to the US Census Bureau, 80% of Americans live in urban cities, bustling with jobs and opportunities. However, a large proportion of urbanites expressed desire for suburban and rural life. Their reasons? Chronic underinvestment in infrastructure, housing, and transportation that often leads to crowding and One pressing issue congestion. Simultaneously, they decried the rampant crime and in America’s poverty that sullies city image. burgeoning urban Urban planning is a dynamic field that involves studying the landscape is development and design of metropolitan land to improve the lives of sustainable and city-dwellers. Urban planning requires detailed, futuristic policies efficient and regulations at the local, state, and national level to prevent a transporation. mass exodus from metro cities. Urban planning asks questions like: Oceans of Data Where will people live and work in the future? How can we ensure environmentally sustainable mobility? How will electrical grids, water supplies and sewers fit into the city? How will we regulate businesses and provide social services? XPLANATION OF THE SSUE Urban planning E I takes inspiration Historical Development from early pre- Classical cities. Early Origins Urban Planning takes inspiration from cities throughout history, as early as the pre-Classical period. These early cities were laid out as grids with a hierarchy of streets and alleys that were intended to HARVARD MODEL CONGRESS provide privacy and protect people from noise. This pre-Classical concern for the quality of residential life lives on in modern neighborhood models. -

THE INTERNATIONAL OPIOID CRISIS by Lainey Newman

THE INTERNATIONAL OPIOID CRISIS By Lainey Newman INTRODUCTION In Lomé, the capital city of Togo in West Africa, a man named Lucien woke up at 10 a.m. in his auto repair shop feeling weak and unable to move. Knowing he couldn’t sacrifice a day on the job, Lucien took several tablets of tramadol to ease his pain. Tramadol is a synthetic opioid-based painkiller. Its use has been spreading The World Health rapidly throughout the Middle East and Africa. Lucien told The Organization Lancet medical journal that his friends told him about “this medicine estimates that 27 that gives you strength.” Little did he know that shortly after he million people began taking the painkillers, he would become mentally and worldwide suffered physically debilitated from them. from opioid use In Togo, tramadol is technically a prescription drug, but the drug disorders in the is pervasive and easily accessible. Lucien and his friends purchase year of 2016. tramadol from street vendors that also sell cigarettes, foods, and Photo: Michigan other medicines. The drug is primarily manufactured in China and Health Blog India. Countries everywhere are experiencing the international opioid epidemic. Opioid drugs can be both used and abused. There are many cases in which opioid drugs are necessary to ameliorate severe pain that individuals experience. However, opioids can also be abused when they are used without medical reason for the purpose of “getting high.” The manifestations of the epidemic vary across regions and nations. In the United States, the opioid epidemic claimed over 130 lives per day in the year 2018. -

Harvard Model Congress Dubai

HARVARD MODEL CONGRESS DUBAI 2017 Welcome! We are so excited to host you and your students at the fourth annual Harvard Model Congress Dubai conference, which will take place in Dubai, UAE at the American University in Dubai (AUD) on January 19-21, 2017. Harvard Model Congress Dubai (HMCD) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization run entirely by Harvard University students who are passionate about politics, international relations, and international education. Above all, HMCD is committed to providing an immersive educational experience for high school students from across the globe. We attract the leaders of tomorrow to tackle sensitive political questions today, under the close mentorship of Harvard students. Over the past three years, we have had the opportunity to work with hundreds of students from countries all over the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa. We are thrilled to continue our tradition of excellence in education, and have already begun implementing improvements for the coming conference. Our Executive Board has big plans for this year, focusing on expanding our student attendance and deepening our relationships with delegates and you, the faculty. The goal is to make HMCD a lasting experience for you and your students not just during the weekend of the conference, but for the entirety of the year. Throughout the intensive three-day conference, students will work closely with their committees to debate briefings written by Harvard students and draft legislation to be presented in full sessions. In previous HMCD conferences, delegates have written over thirty bills and resolutions during the conference. Students have the opportunity to present their ideas to their peers and learn to compromise to get their legislation to pass. -

SF Reg Guide 2005.Qxd

HARVARD MODEL CONGRESS 2005 NTRODUCTION Table of Contents I “Freedom,” wrote Thomas Jefferson, “is the first-born daughter of sci- ence.” The success of a democracy depends on the informed and dynam- ic participation of its citizens; the future of any democratic state is only Introduction 1 as bright as the intellect of its next generation of citizens and leaders. Harvard Model Congress recognizes the need to prepare students for meaningful involvement in our nation’s government and society. To this end, HMC’s comprehensive program of carefully designed simulations include all three branches of the American federal government, along Program Overview: with a diversity of special programs which encompass the full spectrum of inside-the-beltway activity. The Congress 2 The scope and depth of knowledge imparted by these role-playing simu- lations offer students valuable hands-on experience as they become politi- Special Programs 4 cians, lawyers, bureaucrats, journalists, and judges for four days. This is more than simple “exposure”; students gain an understanding of the The Conference 6 important issues facing society and how they are addressed by institutions in our political system through active participation. Educators regularly comment that HMC’s four-day conference can often teach more than a semester in the classroom. Preparation: Every element of HMC’s dynamic program helps students learn about national problems and how to solve them. Before the conference, stu- dents are assigned roles and topics to research, enabling them not only to Overview 7 become experts on substantive policy issues, but also to confront the challenge of presenting the perspectives of the political figure whom they Faculty Preparation 8 are portraying. -

NATO Guide.Pmd

Harvard Model Congress Europe 1956 HISTORICAL NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION Committee Guide BY BRIAN COYNE Introduction The Historical Committee is endowed with the unique power to rewrite history. Using a critical historical event in world diplomacy as its starting point, the committee has the opportunity to re-chart the course of the events that actually transpired. This year, the Historical Committee will take up the role of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in the tumultuous year 1956. That year saw Cold War tensions escalate with the Soviet invasion of Hungary, the Suez Crisis, and the beginning of the Algerian War of Independence. Going Back in Time We are all accustomed to thinking of the past as immutable and finished, but for the purposes of HMCE’s historical committee the events of the late 1956 are not the past but the present and future. By going back in history we aim not to replicate it, but rather to explore the variety of paths world events could have taken by reenacting the decisions that faced world leaders at the time. For them and for you, history is not yet written, and events certainly do not have to turn out the way they actually did. Indeed, any number of events, ideas, and choices, both profound and apparently trivial, could have changed the course of history. The 18th century French philosopher Voltaire once proposed that he could prove that the modern world would be a very different place had Cleopatra had a differently shaped nose. His exaggeration highlights the truth behind his jest. Why NATO? Why 1956? The Historical Committee chose to recreate NATO in 1956 because the people gathered there had immense capacity to shape the course of world events. -

Trustees Visit Classes by TOM HOFF ‘11 Classes

The Walrus The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things: Of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages and kings. - Lewis Carroll Vol LXIII, No. 5 St. Sebastian’s School March 2010 Harvard Model Congress Trustees Visit Classes BY TOM HOFF ‘11 classes. However, beyond religion Apparently, the trustees were very classes, many were impressed with overjoyed when relaying their Gets the Job Done On Thursday, the 4th, many trustees the teachers’ use of technology, impressions to Mr. Nerbonne about visited numerous classes here at St. and Mr. Nerbonne reinforced what I how teachers suggested to students Sebs. According to Mr. Nerbonne, had heard on these subjects: “In the in the classes that they should the trustee visit is “an annual event meeting that followed the day’s hap- receive extra help. At other schools, when the trustees send in requests penings, I heard so much about the including the high schools that to see three departments that great things that the trustees saw. most of the trustees probably went interest them, and they see what They talked about student – teacher to, teachers wouldn’t really want to happens in some classes of one of relationships, energy and enthusi- stay after 2:30 or whenever school those departments.” During the asm, the quality of instruction and ended. Some may even be like the day, many wishing to learn more how the teachers made sure that teachers in The Hangover, when the about the daily life of our school sat the students understood everything, teachers says that “School’s over, it’s in on classes. -

THE ECONOMICS of OUR CLIMATE CRISIS by Trisha Prabhu

THE ECONOMICS OF OUR CLIMATE CRISIS By Trisha Prabhu INTRODUCTION Today, one of the most - arguably, the most - important issue facing humanity is human-caused climate change. Climate change not only threatens our Earth, but the almost 8 billion individuals who live here. Indeed, estimates find that 800 million people - or around 11% of the population - are vulnerable to the immediate effects of climate change, such as droughts, floods, or extreme weather events (“Climate Change” 2020). Experts predict that tourist attractions - place you know and likely love - like the Everglades and Miami This is what a Beach, will be submerged by the end of the century (Cusick 2020). parking lot in Second to the humanitarian crisis that climate change will bring Miami Beach, FL, is the economic crisis that will surely follow. Infrastructure will be looked like before destroyed. Economic output will be reduced. Adaptation and change the onset of will cost billions, if not trillions of dollars. Perhaps most concerning: Hurrican Dorian. despite these realities, most Americans and global citizens/nations Some experts remain disincentivized to confront the economics of our climate believe this may be crisis. This leads to a key question: how do we best estimate, mitigate, a more permanent and begin preparation for the economic effects of climate change? picture. In this briefing, we’ll try to answer that question; namely, we’ll Scientific American explore the economics of climate change. As Congress(wo)men, it will be your job to critically evaluate the information presented - a deep dive into the various facets of the problem at hand, a review of past action, an analysis of pertinent ideological viewpoints, and a range of potential solutions - and determine where you stand. -

Seven Delegate Categories

May 2019 // Issue 4 UNMOD A MODEL UN MAGAZINE FOR MODEL UN PEOPLE From a Model UN conference in China to Cambridge PG. 4 The Ideal Faculty Advisor PG. 10 SEVEN The Long Island DELEGATE Model UN Circuit PG. 3 CATEGORIES THE SEVEN TYPES OF DELEGATES THAT YOU’LL MEET IN EVERY COMMITTEE UNLOCK THE WORLD WITH MODEL UN Join a Model UN community dedicated to improving themselves and supporting each other: 95% of our student win individual awards at conferences, our teams have won delegation awards at every conference, and 34% of our alumni attend an Ivy League+ school. ALL-AMERICAN MODEL UN All-American Model UN Programs “Being an All-American has • Harvard Model Congress– Madrid, Spain (March) changed my life. I have • NATO Security Summit— Warsaw, Poland (June) learned so much, not only • Diplomacy Academy– Boston, MA (July) about MUN, but also about • Harvard Model UN India– Hyderabad, India (August) the world, history, politics, and • Yale Model Government Europe– Budapest, even about people. If you want Hungary (November) that life changing experience, apply for any program— I’ve Applications Open! done 3 and have never been disappointed.” allamericanmun.com contents may 2019 up front C ALICE BENNETT PORTRAIT IN INDIA (JAEBOK LEE, PHOTOGRAPHER) features profile 3 AN INSIDER’S PERSPECTIVE ON THE CULT OF LONG ISLAND MUN The world of Model UN on the Long Island circuit is fierce— they’ll cut each other down before defending each other with zeal. 4 BEN SCHAFER’S JOURNEY FROM CHINA TO CAMBRIDGE Ben Schafer is an All-American superstar. -

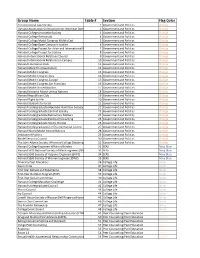

2019 Involvement Fair Tables List

Group Name Table # Section Flag Color Constitutional Law Society 1 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Association Cultivating Inter-American Democracy 2 Government and Politics Orange Harvard College Anscombe Society 3 Government and Politics Orange Harvard College Democrats 4 Government and Politics Orange Harvard College Model Congress Middle East 5 Government and Politics Orange Harvard College Open Campus Initiative 6 Government and Politics Orange Harvard College Project for Asian and International Relations 7 Government and Politics Orange Harvard College Project for Justice 8 Government and Politics Orange Harvard International Relations Council 9 Government and Politics Orange Harvard International Relations on Campus 10 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Libertarian Club 11 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Mock Trial Association 12 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Model Congress 13 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Model Congress Asia 14 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Model Congress Europe 15 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Model Congress San Francisco 16 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Model United Nations 17 Government and Politics Orange Harvard National Model United Nations 18 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Republican Club 19 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Right to Life 20 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Students for Israel 21 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Undergraduate Alexander Hamilton Society 22 Government and Politics Orange Harvard Undergraduate -

HMCA+Registration+Guide+2021.Pdf

1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 President’s Welcome Letter 4 About Harvard Model Congress Asia 5 At the Conference 8 Venue 9 10 Tentative Conference Schedule 11 Registration 13 Scholarships Initiative Conference Committees 14 Delegate Preparation 18 Awards 20 2 Introduction Greetings from Cambridge, Massachusetts! In the following pre-registration guide, you will find an overview of Harvard Model Congress Asia (HMCA), its academic purpose, and its programs. Harvard Model Congress is an educational government simulation program for secondary school students. Over the course of the conference, students gather to debate, share, learn, and compromise on pressing issues while taking the positions of some of the most important leaders in the world. For over a decade, Harvard Model Congress Asia has th attracted students from across the continent and beyond. As we celebrate our 17 conference, we invite you to join us for Harvard Model Congress Asia 2021, which will be held online from January 8-10, 2021. Below you will find an introduction to our program and the Harvard Model Congress experience, as well as how to register for our conference. While this is by no means a complete step-by-step outline of the process for students, our guide should provide you with a general overview of Harvard Model Congress Asia. You will find information about the conference and its history, descriptions of committees and the program structure, and materials on logistical questions and the registration process. We invite you to learn more about the conference through this packet. You can also learn more about us through our website at hmcasia.org and through social media.