An Experts' Guide to International Protocol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council of the European Union

ISSN 1680-9742 QC-AA-05-001-EN-C EN EN COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION GENERAL SECRETARIAT European Union - Union European EU Annual Report This, the seventh EU Annual Report on Human Rights, records the actions and policies undertaken by the EU between 1 July 2004 and 30 on Human Rights June 2005 in pursuit of its goals to promote universal respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. While not an exhaustive account, it Rights-2005 onHuman Annual Report highlights human rights issues that have given cause for concern and what the EU has done to address these, both within the Union and outside it. 2005 EU Annual Report on Human Rights 2005 EU Annual Report on Human Rights, adopted by the Council on 3 October 2005. For further information, please contact the Press, Communication and Protocol Division at the following address: General Secretariat of the Council Rue de la Loi 175 B-1048 Brussels Fax: +32 (0)2 235 49 77 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ue.eu.int Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this edition. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2005 ISBN 92-824-3179-7 ISSN 1680-9742 © European Communities, 2005 Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes , provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................................................7 2. Developments within the EU ...................................................................................................................8 2.1. -

Correspondence Manual

ST/AI/102/Revo 3 Correspondence Manual j|k UNITED 40 HÂTIONS Correspondence Manual ЖШ& (JNITED ## NATIONS New York, 1968 ST/Al/102/Rev.3 I актшшвяаи» January 1968 UNITED NATIONS CORRESPONDENCE MANUAL This manual replaces the edition published in 1962. It has been prepared, with the assistance of the correspondence officers of all departments, by the Registry Section of the Communications, Archives and Records Service, Office of General Services. Questions concerning its content should be directed to that office. Copies of the manual may be obtained through the Distribution Section of the Publishing Service. Similar manuals are available in French and Spanish. All staff members concerned with the drafting, typing or dispatch of official communications are urged to familiarize themselves with the manual and to observe the prescribed regulations and procedures. Although the manual is directed primarily to Headquarters' needs, the broad policies and procedures are of general applicability; it is expected that offices away from Headquarters will follow these instructions, suitably adapting them to local practice. David В. VAUGHAN Assistant Secretary-General Director of General Services Approved: С V. NARASIMHAN Under-Secretary-General Chef de Cabinet Blank page Page blanche CONTENTS ^^ ^ Pile number ^ ^Initials 8 Re50o^5^l^^^o^e5po^de^e ^Date 8 1.General ^ margins 8 ^Spacing 8 ^.Correspondence officers ^Indention 8 ^.Clearance ofoutgoing correspondence.... ^ numbering of pages 8 ^ Salutation, text and complimentary closD ^Signature of correspondence ing 8 ^.Correspondence and records services.... ^ Signature bloc^ 9 ^Address 9 6.^ist of Official Addresses and Official ^ enclosures 9 Correspondence Card Index ^Assembly and dispatch 10 20. Interoffice memoranda 10 ^ Paper and envelopes 10 ^Copies 10 ^ Heading 10 ^Initials 10 ^.General 2 ^ margins 11 ^Spacing 11 8. -

Science and Art of the Diplomatic Protocol -- Alina Bugar

Science and Art of the Diplomatic Protocol -- Alina Bugar Alina Bugar Founder, Art of Protocol [email protected] www.artofprotocol.com www.facebook.com/Art-of-Protocol-771515066245956/ There are many instruments which make a complex and delicate mechanism of foreign policy work successfully and effectively and the diplomatic protocol is one of the most important among them. In fact, it is the core of everything related to diplomacy. Any diplomatic activity is simply impossible to imagine without diplomatic traditions and rules. Protocol is a set of the established traditions and rules, a form of each foreign policy action of a state and its official representatives. Diplomatic ceremonial, in turn, means a strict adherence to established procedures. There has never been any public institution in the world, which existed without hierarchy and no civilization has ever existed without ceremonies. There has been a need of order since the very emergence of society. In the modern world ceremony based on traditions and national features has become universal. Diplomatic protocol is so important worldwide for its ability to create a friendly atmosphere in relations between the governments and their official representatives. Protocol codifies the ceremonial rules, puts them into practice and controls their implementation at the same time. According to the definition written by John Wood and Jean Serres in the book Diplomatic Ceremonial and Protocol, etymologically, the word "protocol" in the Byzantine diplomacy used to mean the first part of the ceremonial speech document with the list of all participants. The concept of the state protocol exists in the practice of each country. -

Georgia Protocol Guide Table of Contents

GEORGIA PROTOCOL GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: What is protocol? .........................................................................................................3 Message from Governor Nathan Deal ..............................................................................................4 Georgia Department of Economic Development International Relations Division............................5 Georgia Code ...................................................................................................................................6 A. Precedence ..................................................................................................................................6 B. Forms of Address .................................................................................................................. 7-12 • The Honorable ........................................................................................................................7 • His/Her Excellency .................................................................................................................7 • Former Elected Office Holders ................................................................................................7 • Federal Officials ......................................................................................................................8 • State Officials ..........................................................................................................................9 • Judicial Officials ....................................................................................................................10 -

Protocol for the Modern Diplomat, and Make a Point of Adopting and Practicing This Art and Craft During Your Overseas Assignment

Mission Statement “The Foreign Service Institute develops the men and women our nation requires to fulfill our leadership role in world affairs and to defend U.S. interests.” About FSI Established in 1947, the Foreign Service Institute is the United States Government’s primary training institution for employees of the U.S. foreign affairs community, preparing American diplomats and other professionals to advance U.S. foreign affairs interests overseas and in Washington. FSI provides more than 600 courses – to include training in some 70 foreign languages, as well as in leadership, management, professional tradecraft, area studies, and applied information technology skills – to some 100,000 students a year, drawn from the Department of State and more than 40 other government agencies and military service branches. FSI provides support to all U.S. Government employees involved in foreign affairs, from State Department entry-level specialists and generalists to newly-assigned Ambassadors, and to our Foreign Service National colleagues who assist U.S. efforts at some 270 posts abroad. i Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Protocol In Brief ............................................................................................................................. 2 International Culture ....................................................................................................................... 2 Addressing -

Is an Ultimatum the Last Word on Crisis Bargaining?

Is an Ultimatum the Last Word on Crisis Bargaining? Mark Fey∗ Brenton Kenkely March 1, 2019 Abstract We investigate how the structure of the international bargaining process affects the resolution of crises. Despite the vast diversity in bargaining protocols, we find that there is a remarkably simple structure to how crises may end. Specifically, for any equilibrium outcome of a complex negotiation process, there is a take-it-or-leave-it offer that has precisely the same risk of war and distribution of benefits. In this sense, every equilibrium outcome of a crisis bargaining game is equivalent to the outcome of an offer in the ultimatum game. Consequently, if a state could select the bargaining protocol, it would choose an ultimatum or another protocol with the same result. According to our model, if states are behaving optimally, then we should observe no relationship between the bargaining protocol and the risk of war or distribution of benefits. An empirical analyses of ultimata in international crises supports this claim. ∗Professor, Department of Political Science, 109 Harkness Hall, University of Rochester, Rochester NY 14627. Email: [email protected]. yCorresponding author. Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, 324 Commons Center, Vanderbilt University, Nashville TN 37203. Email: [email protected]. 1 Introduction One of the main tenets of the international conflict literature is that war is the result of bargaining failure. To understand why states fight each other, we must identify why they were not able to reach a deal at the bargaining table (Fearon 1995). In other words, to understand war we must understand pre-war negotiations. -

Domestic Workers in Diplomats' Households

Study Domestic Workers in Diplomats’ Households Rights Violations and Access to Justice in the Context of Diplomatic Immunity Angelika Kartusch Imprint The Institute Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte The German Institute for Human Rights is the inde- German Institute for Human Rights pendent National Human Rights Institution in Ger- Zimmerstr. 26/27 many. It is accredited according to the Paris Principles 10969 Berlin of the United Nations (A-Status). The Institute’s activ- Phone: (+49) (0)30 25 93 59 - 0 ities include the provision of advice on policy issues, Fax: (+49) (0)30 25 93 59 - 59 human rights education, applied research on human [email protected] rights issues and cooperation with international organ- www.institut-fuer-menschenrechte.de izations. It is supported by the German Federal Minis- try of Justice, the Federal Foreign Office, the Federal Cover photograph: Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development Ms Jacob Langford and the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. The National Monitoring Body for the UN Convention Typesetting: on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was estab- Wertewerk, Tübingen lished at the Institute in May 2009. June 2011 The project “Forced Labor Today - Empowering Traf- ficked Persons” is carried out by the Institute since ISBN 978-3-942315-17-3 (PDF) 2009 in cooperation with the Foundation “Remem- brance, Responsibility and Future” (EVZ). The research © 2011 Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte for this study has been undertaken as part of the pro- German Institute for Human Rights ject, funded through the Foundation EVZ. The study All rights reserved was printed at the expense of the Institute. -

Alternative Diplomacy

INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL "SCIENCE. BUSINESS. SOCIETY" WEB ISSN 2534-8485; PRINT ISSN 2367-8380 ALTERNATIVE DIPLOMACY АЛТЕРНАТИВНАТА ДИПЛОМАЦИЯ PhD Student, Rusinova, D.Z Veliko Turnovo University, Bulgaria [email protected] Abstract: Without claiming to be exhaustive, this paper aims at analyzing the tools of alternative (Track II and III diplomacy) for conflict resolution and crisis management. In order to maximize the gains from private diplomacy, the EU should take into account what Track II and III diplomacy has done so far to help solve conflicts, why it is need and how it can best be used. KEY WORDS: DIPLOMACY, NEGOTIATIONS, PRIVATE, INTERVENTION, EU, MEDIATION, CONFLICT, APPROACH, RESOLUTION, RESULT 1. Introduction opinion, organize human and material resources in ways that might help resolve their conflict”8 Montville emphasized that Track Two Diplomacy is not a substitute for Track One Diplomacy in its multilayered meaning represents a formulation Diplomacy, but compensates for the constraints imposed on and implementation of foreign politics, technique of foreign leaders by their people’s psychological expectations. Most politics, international negotiations and professional activity, 1 important, Track Two Diplomacy is intended to provide a bridge which is being performed by the diplomats Diplomacy can be or complement official Track One negotiations . Examples of simply defined as a primary method with which foreign politics Track Two organisations are Search for Common Ground, West is realized and as normal means of communication in 2 African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), European Centre international relations . In representation of one of the authors for Conflict Prevention (ECCP), and many others. »the (foreign) politics is a formulation and a direction; and the diplomacy a communication and realization. -

The Protocol Advantage Protocol Library

Protocol The Protocol Advantage Library Functioning in today's global environment requires an ability to deal with people of diverse backgrounds and customs. In addition to a thorough understanding of what is expected in your position, having a working knowledge of different traditions, sensitivity to cross‐cultural distinctions and a mastery of modern protocol and advance techniques are critical to achieving success. This continuing series provides executives and officials with the orientation they need to be informed and at ease when interacting and negotiating with international counterparts. www.ePROTOCOL.us [email protected] The following is a list of books, documents and other publications on the subject of protocol, etiquette, business customs, dining practices, cultural diversity and other related issues. Additions, corrections and updates are always welcome and much appreciated. We sincerely thank the Los Angeles County Office of Protocol for contributing to this listing. Items are available for loan through the Resource Section and can be requested electronically at info.ePROTOCOL.us. Acuff, Frank L. How to Negotiate Anything with Anyone Anywhere Around the World. American Management Association, New York 1993 A Dictionary of Heraldry. Friar, Stephen. ed., Harmony Books, New York 1987 Adlerstein, Marion von. Australia Vogue, Guide to Good Form. Bernard Leser Publications Pty. Ltd. under license from The Condé Nast Publications, Inc. New York. 1986 (124 page magazine, special issue) Aikman, Lonnelle. The Living White House. White House Historical Association, Washington, D.C. 1982 Albright, Madeleine. Read My Pins: Stories from a Diplomat’s Jewel Box. Melcher Media, New York 2009 Allsebrook, Mary. Prototypes of Peacemaking: The First Forty Years of the United Nations. -

Protocol Handbook 2018

PROTOCOL HANDBOOK PROTOCOL DIVISION MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PREFACE It gives me immense pleasure in presenting this edition of the Protocol Handbook. I would like to give credit to my predecessor Shri Sanjay Verma, in whose tenure compilation of this edition was almost completed. The last edition of the Protocol Handbook was published in 2006. Since then, some policy and procedural changes have taken place in respect of privileges, immunities and facilities extended to Diplomatic Missions/Consular Posts and UN/Other International Organizations [Foreign Representations (FRs)] in India. Protocol Division has also taken several steps to simplify and streamline procedures for interaction between FRs and Ministry of External Affairs. Application forms for all services have been placed at the Website of the Ministry under URL <http://meaprotocol.nic.in>. This edition of the Protocol Handbook is an effort to incorporate consequent changes in rules, regulations and guidelines on Protocol issues and make them user-friendly with ample cross referencing and links to relevant Websites. A special feature of the Handbook is addition of subject ‘Goods & Service Tax’ (GST) under Chapter XVI and change of nomenclature of Chapter XIX from ‘Foreign Cultural Centres and Assistance to Indian Cultural/Friendship Societies’ to ‘Guidelines for Establishment and Functioning of Foreign Cultural Centres’. In addition, new Chapters XXXIV to XXXVII have been incorporated for better clarity on the respective subjects. The contents of the Handbook are available at the Website of the Ministry under URL <http://meaprotocol. nic.in>. The Protocol Handbook should address, in a large measure, the most frequently asked questions. -

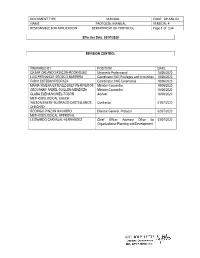

DP-MA-02 NAME PROTOCOL MANUAL VERSION: 4 RESPONSIBLE for APPLICATION DEPARTMENT of PROTOCOL Page 1 of 134

DOCUMENT TYPE MANUAL CODE: DP-MA-02 NAME PROTOCOL MANUAL VERSION: 4 RESPONSIBLE FOR APPLICATION DEPARTMENT OF PROTOCOL Page 1 of 134 Effective Date: 03/07/2020 REVISION CONTROL PREPARED BY POSITION DATE CESAR ORLANDO RINCÓN-RODRIGUEZ University Professional 18/06/2020 LUIS FERNANDO OROZCO-BARRERA Coordinator IWG Privileges and Immunities 18/06/2020 FABIO ESTEBAN PEDRAZA Coordinator, IWG Ceremonial 18/06/2020 MARIA XIMENA ESTEVEZ-BRETÓN-RIVEROS Minister-Counsellor 18/06/2020 GEOVANNY ÁNGEL GUILLEN-MENDOZA Minister-Counsellor 18/06/2020 CLARA ELENA MURIEL-TOBÓN Adviser 18/06/2020 METHODOLOGICAL CHECK WILSON ENERY BUITRAGO-CASTELLANOS Contractor 01/07/2020 CHECKED RODRIGO PINZON NAVARRO Director General, Protocol 02/07/2020 METHODOLOGICAL APPROVAL LEONARDO CARVAJAL-HERNÁNDEZ Chief Officer Advisory Office for 03/07/2020 Organizational Planning and Development DOCUMENT TYPE MANUAL CODE: DP-MA-02 NAME PROTOCOL MANUAL VERSION: 4 RESPONSIBLE FOR APPLICATION DEPARTMENT OF PROTOCOL Page 2 of 134 Contenido 1. OBJECTIVE ....................................................................................................................................... 8 2. SCOPE .............................................................................................................................................. 8 3. BASIS IN LAW ................................................................................................................................... 8 4. DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................... -

United Nations Correspondence Manual

ST/DCS/4/Rev.1 United Nations Correspondence Manual A guide to the drafting, processing and dispatch of official United Nations communications United Nations ST/DCS/4/Rev.1 Department of General Assembly Affairs and Conference Services United Nations Correspondence Manual A guide to the drafting, processing and dispatch of official United Nations communications United Nations • New York, 2000 1RWH 6\PEROVRI8QLWHG1DWLRQVGRFXPHQWVDUHFRPSRVHGRIFDSLWDOOHWWHUVFRPELQHGZLWK ILJXUHV0HQWLRQRIVXFKDV\PEROLQGLFDWHVDUHIHUHQFHWRD8QLWHG1DWLRQVGRFXPHQW 8QLWHG1DWLRQ3XEOLFDWLRQ 6DOHV1R(, ,6%1 &RS\ULJKW8QLWHG1DWLRQV $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 3ULQWHGLQWKH8QLWHG6WDWHVRI$PHULFD Introductory note The United Nations Correspondence Manual is intended to serve as a guide to the drafting of official correspondence in English, the processing and dispatch of offi- cial communications and the handling of incoming and outgoing communications. The present revised version supersedes the United Nations Correspondence Manual issued in 1984 (ST/DCS/4) and contains new sections on electronic communications. Although the Manual is concerned primarily with policies and practices at Headquarters, the broad policies and procedures set forth here are of general appli- cability and it is expected that offices away from Headquarters will follow these in- structions, adapting them to local needs if necessary. The Manual was prepared by the Interpretation, Meetings and Publishing Divi- sion and the Translation and Editorial Division of the Department of General As- sembly Affairs and Conference Services with the assistance of the Staff Develop- ment Services, Office of Human Resources Management, and the Information Technology Services Division and the Special Services Section of the Facilities Management Division, Office of Central Support Services. v Contents Chapter Paragraphs Page I. Introduction ...................................................................... 1–2 1 II. Responsibility for correspondence ............................................ 3–11 2 A.