Vice President Garret A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-House. April 24

5476 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. APRIL 24, By Mr. WILSON of lllinois: A bill (H. R. 15397) granting a. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. pension to Carl Traver-to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. Also, a bill (H. R. 15398) to remove the charge of desertion from SUNDAY, .April24, 190.4-. the military record of GeorgeS. Green-to the Committee on Mil The House met at 12 o'clock m. itary Affairs. The following prayer was offered by the Chaplain, Rev. H.E..--rn.Y N. COUDEN, D. D.: PETITIONS, ETC. Eternal and everliving God, our Heavenly Father, we thank Thee for that deep and ever-abiding faith which Thou hast im Under clause 1 of Rn1e XXII, the following petitions and papers planted in the hearts of men, and which has inspired the true, the were laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: noble, the brave of every age with patriotic zeal and fervor, bring By Mr. BRADLEY: Petition of Montgomery Grange, of Mont gomery, N.Y., and others, in favor of the passage of bill H. R. ing light out of darkness, order out of chaos, liberty out of bond 9302-to the Committee on Ways and Means. age, and thus contributing here a. little, there a. little, to the By Mr. CALDERHEAD: Petition of Lamar Methodist Episco splendid civilization of our age. Especially do we thank Thee for pal Church, of Lamar Kans., in favor of the Hepburn-Dolliver that long line of illustrious men who lived and wrought, suffered bill-to the Committee on the Judiciary. -

Slave Housing Data Base

Slave Housing Data Base Building Name: Howard’s Neck, Quarter B Evidence Type: Extant Historical Site Name: Howard's Neck City or Vicinity: Pemberton (near Cartersville, and Goochland C.H.) County: Goochland State: Virginia Investigators: Douglas W. Sanford; Dennis J. Pogue Institutions: Center for Historic Preservation, UMW; Mount Vernon Ladies' Association Project Start: 8/7/08 Project End: 8/7/08 Summary Description: Howards’ Neck Quarter B is a one-story, log duplex with a central chimney and side-gable roof, supported by brick piers, and is the second (or middle) of three surviving currently unoccupied quarters arranged in an east-west line positioned on a moderately western sloping ridge. The quarters are located several hundred yards southwest of the main house complex. The core of the structure consists of a hewn log crib, joined at the corners with v-notches, with a framed roof (replaced), and a modern porch on the front and shed addition to the rear. Wooden siding currently covers the exterior walls, but the log rear wall enclosed by the shed is exposed; it is whitewashed. The original log core measures 31 ft. 9 in. (E-W) x 16 ft. 4 in. (N-S); the 20th-century rear addition is 11 ft. 8 in. wide (N-S) x 31 ft. 9 in. long (E-W). A doorway allows direct access between the two main rooms, which may be an original feature; a doorway connecting the log core with the rear shed has been cut by enlarging an original window opening in Room 1. As originally constructed, the structure consisted of two first-floor rooms, with exterior doorways in the south facade and single windows opposite the doorways in the rear wall. -

To Declare War

TO DECLARE WAR J. GREGORY SIDAK* INTRODUCTION ................................................ 29 I. DID AMERICA'S ENTRY INTO THE PERSIAN GULF WAR REQUIRE A PRIOR DECLARATION OF WAR?................ 36 A. Overture to War: Are the PoliticalBranches Willing to Say Ex Ante What a "War" Is? ...................... 37 B. Is It a Political Question for the Judiciary to Issue a DeclaratoryJudgment Saying Ex Ante What Is or Will Constitute a "War"? .................................. 39 C. The Iraq Resolution of January 12, 1991 .............. 43 D. Why Do We No Longer Declare War When We Wage War? ................................................ 48 E. The President's War-Making Duties as Commander in Chief ................................................ 50 F. The Specious Dichotomy Between "General War" and Undeclared "'Limited War"........................... 56 II. THE COASE THEOREM AND THE DECLARATION" OF WAR: POLITICAL ACCOUNTABILITY AS A NORMATIVE PRINCIPLE FOR IMPLEMENTING THE SEPARATION OF POWERS ........ 63 A. Coasean Trespasses and Bargains Between the Branches of Government ....................................... 64 B. PoliticalAccountability, Agency Costs, and War ........ 66 C. American Sovereignty and the United Nations .......... 71 III. THE ACCOUNTABLE FORMALISM OF DECLARING WAR: LESSONS FROM THE DECLARATION OF WAR ON JAPAN .... 73 A. Provocation and Culpability: Is America Initiating War or Is Pre-Existing War "Thrust Upon" It? ............. 75 B. The Objectives of War: The President'sLegislative Role as Recommender of War .............................. 79 * A.B. 1977, A.M., J.D. 1981, Stanford University. Member of the California and District of Columbia Bars. In writing this Article, I have benefitted from the comments and protests of Gary B. Born, L. Gordon Crovitz, John Hart Ely, Daniel A. Farber, John Ferejohn, Michael J. Glennon, Stanley Hauerwas, Geoffrey P. -

Presidential Illness and Disability: the Health And

PRESIDENTIAL ILLNESS AND DISABILITY: THE HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE OF PRESIDENTS FROM 1789-1901 A THESIS IN Political Science Presented to the Faculty of the of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CHAD LAWRENCE KING B.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2008 Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 CHAD LAWRENCE KING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRESIDENTIAL ILLNESS AND DISABILITY: THE HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE OF PRESIDENTIAL TICKETS FROM 1789-1901 Chad Lawrence King, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT Presidential health and performance has been a subject of study by both political scientists and historians, many of whom have examined the health of our nation’s presidents. This study of presidential history is not new. Many monographs and articles have examined this subject in great detail. While these have led to new interpretations of presidential history, they are inadequate for understanding the problem that presidential ill health and disability have presented during our nation’s history. Most studies focus only on the twentieth century and the importance of health into the modern presidency. While the focus of health on the modern presidency has greatly changed our understanding of individual presidents and their effect on history, it nonetheless presents only a partial picture of the problem, since it neglects the effect of presidential health during the early years of the republic. I argue that presidential health has always been of prime importance and its effect is certainly not limited to recent decades. This study will also focus, when appropriate, on the health of the vice president during certain administrations. -

Download Catalog

Abraham Lincoln Book Shop, Inc. Catalog 183 Holiday/Winter 2020 HANDSOME BOOKS IN LEATHER GOOD HISTORY -- IDEAL AS HOLIDAY GIFTS FOR YOURSELF OR OTHERS A. Badeau, Adam. MILITARY HISTORY OF ULYSSES S. GRANT, FROM APRIL 1861 TO APRIL 1865. New York: 1881. 2nd ed.; 3 vol., illus., all maps. Later full leather; gilt titled and decorated spines; marbled endsheets. The military secretary of the Union commander tells the story of his chief; a detailed, sympathetic account. Excellent; handsome. $875.00 B. Beveridge, Albert J. ABRAHAM LINCOLN 1809-1858. Boston: 1928. 4 vols. 1st trade edition in the Publisher’s Presentation Binding of ½-tan leather w/ sp. labels; deckled edges. This work is the classic history of Lincoln’s Illinois years -- and still, perhaps, the finest. Excellent; lt. rub. only. Set of Illinois Governor Otto Kerner with his library “name” stamp in each volume. $750.00 C. Draper, William L., editor. GREAT AMERICAN LAWYERS: THE LIVES AND INFLUENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS WHO HAVE ACQUIRED PERMANENT NATIONAL REPUTATION AND HAVE DEVELOPED THE JURISPRUDENCE OF THE UNITED STATES. Phila.: John Winston Co.,1907. #497/500 sets. 8 volumes; ¾-morocco; marbled boards/endsheets; raised bands; leather spine labels; gilt top edges; frontis.; illus. Marshall, Jay, Hamilton, Taney, Kent, Lincoln, Evarts, Patrick Henry, and a host of others have individual chapters written about them by prominent legal minds of the day. A handsome set that any lawyer would enjoy having on his/her shelf. Excellent. $325.00 D. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R. E. LEE: A BIOGRAPHY. New York, 1936. “Pulitzer Prize Edition” 4 vols., fts., illus., maps. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. J .Anualiy 26

1220 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. J .ANUAliY 26, Philadelphia, Pa., indorsing House bill No. 887, to provide for passage of the bill to establish an admiralty court at Buffalo, adding and completing specimens and productions, etc., to be ex N. Y.-to the Committee on the Judiciary. hibited in the Philadelphia museums-to the Committee on Inter Also, papers in behalf of the people of the Seneca Nation, New state and Foreign Commerce. York Indians-to the Committee of Indian Affairs. By Mr. BURLEIGH: Petition of post-office clerks of Augusta, By Mr. SHACKLEFORD: Petitions of the publishers of the Me., in favor of the passage of House bill No. 4351-to the Com Weatherford Democrat, Granville Herald, Shiner Ga2ette, Shn mittee on the Post-Office and Post-Roads. .lenburg Sticker, Corsicana Truth, Lancaster Herald, Denton Moni By Mr. CLARK of Missouri: Protest of the American Federa tor, Bonham News, Comanche Exponent, Dublin Progress, Myrtle tion of Labor, against the· ceding of large areas of the public Springs Herald, Georgetown Sun, Circo Roundup, Honey Grove domain to individuals and corporations-to the Committee on Citizen, Bryan Eagle, Greenville Observer, Greenville Independ Labor. ent Farmer, Jacksonville Reformer, Goldthwaite Eagle, Farmers By Mr. COWHERD: Papers to accompany House bill granting ville Times, Garland News, Brenham Banner, Hillsboro Mirror, a pension to Gevert Schutte-to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. Temple Times, Waxahachie Enterprise, Gainesville Register, By Mr. DALZELL: Resolutions of Manufacturers' Club of Itasca Item, Longville Times-Clarion, and Henderson Times, all· Philadelphia, Pa., indorsing House bill No. 887, to provide for in Texa.s; NewYorkMillsUusi Kotimaa, Minnesota; Dover (Del.) adding to and completing specimens and productions, etc., to be Sentinel, Gloucester (Mass.) Breeze, Willows (Cal.) Journal, exhibited in the Philadelphia museums-to the Committee on Waukegan (Ill.) Gazette, Toronto (Ohio) Tribune, Cleveland Interstate and Foreign Commerce. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, ARCH OIT 45, 01/15/2009

c (' UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY ro WASHINGTON, D.C. · 20460 JAN 1 5 2009 &EPA'~;;:IPttiectioo Office of Pesticide Programs Arch Chemical, Inc. 1955 Lake Park Drive, Suite 100 Smyrna, GA 30080 . Attention: Garret B. Schifilliti Senior Regulatory Manager Subject: Arch OIT 45 EPA Registration No. 1258-1323 Your Amendment Dated December 16,2008 This will acknowledge receipt of your notification of changes to the Storage and Disposal Statements for the "Container Rule", submitted under the provisions of FIFRA Section 3(c)(9). Based on a review of the submitted material, the following comments apply. The Notification dated December 18, 2008 is in compliance with PR Notice 98-10 and is acceptable. This Notification has been added to your file. If you have any questions concerning this letter, please contact Martha Terry at (703) 308-6217. Sincerely ~h1'b Marshall Swindell ~ Product Manager (33) Regulatory Management Branch 1 Antimcrobials Division (7510C) ( ( Forrt., _oroved. O. _No. 2070-0060 . emir.. 2·28·95 United States Registration OPP Identifier Number &EPA Environmental Protection Agency Amendment Washington, DC 20460 @.;. Other· Application for Pesticide - Section I 1. Company/Product Number 2. EPA Product Manager 3. Proposed Classification 1258-1323 Marshall Swindell [2] None D Restricted 4. Company/Product (Name) PM' Arch OIT 45 5. Nama and Address of Applicant (Include ZIP Code) 6. Expedited Reveiw. In accordance with FIFAA Section 3(c)(3) Arch Chemicals, Inc. (b)(il. my product is similar or identical in composition and labeling to: 1955 Lake Park Drive EPA Reg. No. ________________________________ Smyrna, GA 30080 D Check if this is a neW address Product Name Section - II Amendment - Explain below. -

California Licensed Contractor ©

WINTER/SPRING 2011 California © Licensed Contractor Stephen P. Sands, Registrar | Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor 2011 Contracting Laws That Affect You CSLB Has an Licenses for Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) Coming App for That The passage of Senate Bill 392 (and various provisions of the Contractors State License Law CSLB recently including B&P Code Sections 7071.65 and 7071.19) authorizes CSLB to issue contractor launched its new licenses to limited liability companies (LLCs). The law says that CSLB shall begin processing “CSLB mobile” LLC applications no later than January 1, 2012. The LLC will be required to maintain website: www.cslb. liability insurance of between $1,000,000 and $5,000,000, and post a $100,000 surety ca.gov/mobile. bond in addition to the $12,500 bond already required of all licensees. (Senate Bill 392 is CSLB mobile now available at: www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/09-10/bill/sen/sb_0351-0400/sb_392_bill_20100930_ enables users to chaptered.pdf.) check a license, get CSLB office locations, However, do not apply for an LLC license yet; CSLB is not issuing licenses to LLCs at this time. sign up for e-mail alerts, and help report unlicensed activity right from their “smart” CSLB staff is developing new application procedures, creating applications, and putting in phone. place important technology programming changes that are necessary for this new feature. CSLB anticipates that it will be able to accept and process LLC applications late in 2011. “This is an exciting new step for CSLB,” said Registrar Steve Sands. “This application The best way to receive future updates is to sign up for CSLB E-Mail Alerts at www.cslb.ca.gov. -

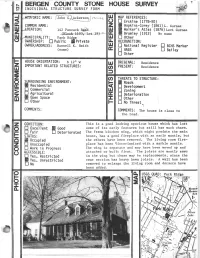

ACCESSIBLE:^^ Byes, Unrestricted

ACCESSIBLE:^^ BYes, Unrestricted CONSTRUCTION DATE/SOURCE: NUMBER OF STORIES: 1-1/2 c. 1770-1810/Architectural evidence CELLAR: B Yes —43 No DC BUILDER: An Ackerson, probably John. CHIMNEY FOUNDATION: O D Stone Arch V) FORM/PLAN TYPE: • Brick Arch, Stone Foundation 111 "F", 5 bay, center hall, 2 rooms deep D Other (32 f 6" x 43'8"). Frame addition Q added as kitchen. FLOOR JOISTS: 6-7" x 9" deep, 23-24" between, 1235-13" floorboards. FRAMING SYSTEM: FIRST FLOOR CEILING HEIGHT: 8'4" ~ In ermed late Bearing Wall FIRST FLOOR WALL THICKNESS: Clear Span 24" L Other GARRET FLOOR JOISTS: Not visible. EXTERIOR MALL FABRIC: GARRET: Well cut red sandstone all around, Unfinished Space except some rubble on west end. B Finished Space ROOF: FENESTRATION: Gable (wing) Not original. 32" x 58" in front, • Gambrel trapezoidal lintels. D Curb D Other ENTRANCE LOCATION/TYPE: EAVE TREATMENT: Plain entrance door in center 37" x 7*5", Sweeping Overhang not original. Supported Overhang (in front) No Overhang D Boxed Gutter D Other This house Is significant for its architecture and its association with the exploration and settlement of the Bergen County, New Jersey area. It is a reasonably well preserved example of the Form/Plan Type as shown and more fully described herein. As such, it is included in the Thematic Nomination to the National Register of Historic Places for the Early Stone Houses of Bergen County, New Jersey. FLOOR PLANS Howard I. Durie believes this house to have been built about 1775 for John G. Eckerson, son of Garret Eckerson, on land Garret and his 0s! cousin Garret Haring purchased on May 4, 1759 from Rev. -

The Prez Quiz Answers

PREZ TRIVIAL QUIZ AND ANSWERS Below is a Presidential Trivia Quiz and Answers. GRADING CRITERIA: 33 questions, 3 points each, and 1 free point. If the answer is a list which has L elements and you get x correct, you get x=L points. If any are wrong you get 0 points. You can take the quiz one of three ways. 1) Take it WITHOUT using the web and see how many you can get right. Take 3 hours. 2) Take it and use the web and try to do it fast. Stop when you want, but your score will be determined as follows: If R is the number of points and T 180R is the number of minutes then your score is T + 1: If you get all 33 right in 60 minutes then you get a 100. You could get more than 100 if you do it faster. 3) The answer key has more information and is interesting. Do not bother to take the quiz and just read the answer key when I post it. Much of this material is from the books Hail to the chiefs: Political mis- chief, Morals, and Malarky from George W to George W by Barbara Holland and Bland Ambition: From Adams to Quayle- the Cranks, Criminals, Tax Cheats, and Golfers who made it to Vice President by Steve Tally. I also use Wikipedia. There is a table at the end of this document that has lots of information about presidents. THE QUIZ BEGINS! 1. How many people have been president without having ever held prior elected office? Name each one and, if they had former experience in government, what it was. -

Broadway East (Running North and South)

ROTATION OF DENVER STREETS (with Meaning) The following information was obtained and re-organized from the book; Denver Streets: Names, Numbers, Locations, Logic by Phil H. Goodstein This book includes additional information on how the grid came together. Please email [email protected] with any corrections/additions found. Copy: 12-29-2016 Running East & West from Broadway South Early businessman who homesteaded West of Broadway and South of University of Denver Institutes of Higher Learning First Avenue. 2000 ASBURY AVE. 50 ARCHER PL. 2100 EVANS AVE.` 2700 YALE AVE. 100 BAYAUD AVE. 2200 WARREN AVE. 2800 AMHERST AVE. 150 MAPLE AVE. 2300 ILIFF AVE. 2900 BATES AVE. 200 CEDAR AVE. 2400 WESLEY AVE. 3000 CORNELL AVE. 250 BYERS PL. 2500 HARVARD AVE. 3100 DARTMOUTH 300 ALAMEDA AVE. 2600 VASSAR AVE. 3200 EASTMAN AVE. 3300 FLOYD AVE. 3400 GIRARD AVE. Alameda Avenue marked the city 3500 HAMPDEN AVE. limit until the town of South 3600 JEFFERSON AVE. Denver was annexed in 3700 KENYON AVE. 1894. Many of the town’s east- 3800 LEHIGH AVE. west avenues were named after 3900 MANSFIELD AVE. American states and 4000 NASSAU AVE. territories, though without any 4100 OXFORD AVE. clear pattern. 4200 PRINCETON AVE. 350 NEVADA PL. 4300 QUINCY AVE. 400 DAKOTA AVE. 4400 RADCLIFF AVE. 450 ALASKA PL. 4500 STANFORD AVE. 500 VIRGINIA AVE. 4600 TUFTS AVE. 600 CENTER AVE. 4700 UNION AVE. 700 EXPOSITION AVE. 800 OHIO AVE. 900 KENTUCKY AVE As the city expanded southward some 1000 TENNESSEE AVE. of the alphabetical system 1100 MISSISSIPPI AVE. disappeared in favor 1200 ARIZONA AVE. -

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam Ho Chi Minh City With focus on the Garment Industry March 2016 By: Research Center for Employment Relations (ERC) A spontaneous market for workers outside a garment factory in Ho Chi Minh City. Photo courtesy of ERC Series 1, Report 10 June 2017 Prepared for: The Global Living Wage Coalition Under the Aegis of Fairtrade International, Forest Stewardship Council, GoodWeave International, Rainforest Alliance, Social Accountability International, Sustainable Agriculture Network, and UTZ, in partnership with the ISEAL Alliance and Richard Anker and Martha Anker Living Wage Report for Urban Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam with focus on garment industry SECTION I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3 1. Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. Living wage estimate ............................................................................................................ 5 3. Context ................................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Ho Chi Minh City .......................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Vietnam’s garment industry ........................................................................................ 9 4. Concept and definition of a living wage ...........................................................................