Wild Abandon: Postwar Literature Between Ecology and Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Notices & the Courts

PUBLIC NOTICES B1 DAILY BUSINESS REVIEW TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021 dailybusinessreview.com & THE COURTS BROWARD PUBLIC NOTICES BUSINESS LEADS THE COURTS WEB SEARCH FORECLOSURE NOTICES: Notices of Action, NEW CASES FILED: US District Court, circuit court, EMERGENCY JUDGES: Listing of emergency judges Search our extensive database of public notices for Notices of Sale, Tax Deeds B5 family civil and probate cases B2 on duty at night and on weekends in civil, probate, FREE. Search for past, present and future notices in criminal, juvenile circuit and county courts. Also duty Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. SALES: Auto, warehouse items and other BUSINESS TAX RECEIPTS (OCCUPATIONAL Magistrate and Federal Court Judges B14 properties for sale B8 LICENSES): Names, addresses, phone numbers Simply visit: CALENDARS: Suspensions in Miami-Dade, Broward, FICTITIOUS NAMES: Notices of intent and type of business of those who have received https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/public-notices/ and Palm Beach. Confirmation of judges’ daily motion to register business licenses B3 calendars in Miami-Dade B14 To search foreclosure sales by sale date visit: MARRIAGE LICENSES: Name, date of birth and city FAMILY MATTERS: Marriage dissolutions, adoptions, https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/foreclosures/ DIRECTORIES: Addresses, telephone numbers, and termination of parental rights B8 of those issued marriage licenses B3 names, and contact information for circuit and CREDIT INFORMATION: Liens filed against PROBATE NOTICES: Notices to Creditors, county -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Maryland Casualty Producer State and General Sections Series 20-07 & 20-08 80 Scored Questions (Plus 10 Unscored)

Maryland Casualty Producer State and General Sections Series 20-07 & 20-08 80 scored questions (plus 10 unscored) Casualty Producer State Section Series 20-08 35 questions- 45-minute time limit 1.0 Insurance Regulation 1.1 Licensing 17% (5 items) Purpose Process (Insurance Article Annotated Code- Sec. 10-115; Sec.10-116; Sec. 10-104) Initial Licensure Qualifications Examination License fee & application Exemptions to Licensure Types of licensees Producers Business entity producers Nonresident producers Temporary Advisers Public insurance adjusters Limited Lines Producer Portable Electronics Insurance Limited Lines license Maintenance and duration (Insurance Article Annotated Code- Sec. 10-116; Sec. 10-117(b)(1)) Reinstatement and renewal Address change Reporting of actions Assumed names Continuing education requirements, exemptions and penalties Disciplinary actions Cease and desist order Hearings Probation, suspension, revocation, refusal to issue or renew Penalties and fines 1.2 State regulation 17% (5 items) Commissioner's general duties and powers (Insurance Article Annotated Code-Sec. 2-205 (a)(2)) State Specific Definitions (Insurance Article Annotated Code- Sec. 10-401; Sec. 27-209; Sec. 27-213; Sec. 10-201; Sec 10-126; Ref: COMAR Sec. 31.08.06.02) Company regulation Certificate of authority Solvency Rates Policy forms Examination of books and records Producer appointments Producer's Contract with Insurer versus Producer's Appointment with Insurer 1 Producer's Individual Appointment versus Business Entity Appointment Maintaining Record of Appointment Notice Termination of producer appointment Producer regulation (Insurance Article Annotated Code-Sec. 27-212(d)) Examination of Books and Records Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Fiduciary Responsibilities (COMAR- Sec. 31.03.03) Bail Bond (COMAR- Sec. -

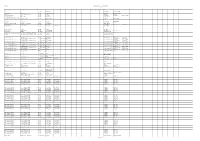

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare

Working Paper The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare Paul Cornish Head, International Security Programme and Carrington Professor of International Security, Chatham House June 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. Working Paper: The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare INTRODUCTION The central features of the ‘cybered’ world of the early 21st century are the interconnectedness of global communications, information and economic infrastructures and the dependence upon those infrastructures in order to govern, to do business or simply to live. There are a number of observations to be made of this world. First, it is still evolving. Economically developed societies are becoming ever more closely connected within themselves and with other, technologically advanced societies, and all are becoming increasingly dependent upon the rapid and reliable transmission of ideas, information and data. Second, where interconnectedness and dependency are not managed and mitigated by some form of security procedure, reversionary mode or redundancy system, then the result can only be a complex and vitally important communications system which is nevertheless vulnerable to information theft, financial electronic crime, malicious attack or infrastructure breakdown. -

A Rhetorical Study of Edward Abbey's Picaresque Novel the Fool's Progress

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2001 A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress Kent Murray Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Rogers, Kent Murray, "A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress" (2001). Theses Digitization Project. 2079. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL,'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 Approved by: Elinore Partridge, Chair, English Peter Schroeder ABSTRACT The rhetoric of Edward Paul Abbey has long created controversy. Many readers have embraced his works while many others have reacted with dislike or even hostility. Some readers have expressed a mixture of reactions, often citing one book, essay or passage in a positive manner while excusing or completely .ignoring another that is deemed offensive. -

Interpreting Class and Work in the Writing of Wendell Berry and Edward Abbey

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2012 Farmer, Miner, Ranger, Writer: Interpreting Class and Work in the Writing of Wendell Berry and Edward Abbey Tyler Austin Nickl Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nickl, Tyler Austin, "Farmer, Miner, Ranger, Writer: Interpreting Class and Work in the Writing of Wendell Berry and Edward Abbey" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1283. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1283 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FARMER, MINER, RANGER, WRITER: INTERPRETING CLASS AND WORK IN THE WRITING OF WENDELL BERRY AND EDWARD ABBEY by Tyler Nickl A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in American Studies Approved: _________________________ _________________________ Melody Graulich Evelyn Funda Major Professor Committee Member _________________________ _________________________ Lawrence Culver Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 ii Copyright © Tyler Nickl 2012 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Farmer, Miner, Ranger, Writer: Interpreting Class and Work in the Writing of Wendell Berry and Edward Abbey by Tyler Nickl, Master of Science Utah State University, 2012 Major Professor: Dr. Melody Graulich Department: English The writings of Wendell Berry and Edward Abbey are often read for their environmental ethics only. -

Civilian Killings and Disappearances During Civil War in El Salvador (1980–1992)

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH A peer-reviewed, open-access journal of population sciences DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 41, ARTICLE 27, PAGES 781–814 PUBLISHED 1 OCTOBER 2019 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol41/27/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.27 Research Article Civilian killings and disappearances during civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) Amelia Hoover Green Patrick Ball c 2019 Amelia Hoover Green & Patrick Ball. This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany (CC BY 3.0 DE), which permits use, reproduction, and distribution in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/legalcode Contents 1 Introduction 782 2 Background 783 3 Methods 785 3.1 Methodological overview 785 3.2 Assumptions of the model 786 3.3 Data sources 787 3.4 Matching and merging across datasets 790 3.5 Stratification 792 3.6 Estimation procedure 795 4 Results 799 4.1 Spatial variation 799 4.2 Temporal variation 802 4.3 Global estimates 803 4.3.1 Sums over strata 805 5 Discussion 807 6 Conclusions 808 References 810 Demographic Research: Volume 41, Article 27 Research Article Civilian killings and disappearances during civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) Amelia Hoover Green1 Patrick Ball2 Abstract BACKGROUND Debate over the civilian toll of El Salvador’s civil war (1980–1992) raged throughout the conflict and its aftermath. Apologists for the Salvadoran regime claimed no more than 20,000 had died, while some activists placed the toll at 100,000 or more. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history.